Numerous governments, some democratic, have capitalized on the COVID-19 infodemic to justify repression of online expression

To curb the global spread of COVID-19, at least 80 countries around the world have enacted emergency declarations in hopes of flattening the curve and slowing the progression of the pandemic. In addition to public health measures and economic stimulus packages, at least 24 countries have issued measures that affect free expression to address the infodemic occurring parallel to the pandemic.

Governments seeking to respond to the surge of unreliable information pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic have implemented new laws that criminalize the act of spreading misinformation and disinformation. While some of these laws have been used to correct and remove false narratives, others have used these laws to censor dissenting voices. This is a particularly concerning trend for countries with strong commitments to democratic values, particularly as many of these emergency measures have few limitations. How nations choose to enforce these measures may have profound consequences for societies and could — in cases where misinformation remains ill-defined and where there is no clear expiration for the expanded powers — pose a grave threat to democratic institutions.

The authoritarian degrees of COVID-19 decrees

Turkey’s response to the infodemic is among the more alarming cases, despite not having declared a state of emergency or passed any specific legislation adopting stricter measures limiting freedom of expression. The Turkish government has an established history of launching investigations into posts made by users under accusations of spreading false information. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis and local outbreaks, the government has intensified these efforts by arresting over 410 people for posting “provocative” messages on social media.

There have also been reports of people being arrested for criticizing the Turkish government for its response. On March 29, truck driver Malik Yilmaz was arrested for posting on his TikTok account that orders to stay at home would render him unable to earn enough money to eat. More broadly, journalists — some of whom already face prosecution from the Turkish government — have been arrested or questioned in conjunction with their coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journalists from the independent agency Bianet were detained by police under charges of spreading panic for reporting factual information on infected cases in Bartın Province. Others have been intimidated into publishing only official statements and refraining from investigative work.

TIR şoförü Malik Baran Yılmaz, 'Evde kal Türkiye ama nasıl kal' diye çektiği videoda evde kal denmesi için önce düzenin değişmesi gerektiğini belirtiyor… pic.twitter.com/XvHiRESuHb

— İSİG Meclisi (@isigmeclisi) March 28, 2020

Thailand reportedly arrested at least two people under charges of violating the controversial Computer Crime Act. This news emerged the same day that Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha issued an emergency decree penalizing the publication of information that “may instigate fear amongst the people or is intended to distort information which misleads understanding of the emergency situation to the extent of affecting the security of state or public order or good moral of the people.” Both the emergency decree and the Computer Crime Act grant the Thai government broad authority to levy penalties with few limitations. In one particular case, a 42-year-old man was arrested and fined for posting a status on Facebook noting the lack of health screenings when processing through Suvarnabhumi Airport in Bangkok. The post, according to authorities, created a panic and undermined the confidence of the public in the airport’s management.

In Honduras, the office of President Juan Orlando Hernández published a decree on March 16 suspending several constitutional rights as part of an effort to limit the spread of COVID-19, which first appeared in the country six days earlier. The next day, several journalists who had gone to the Colonia Lincoln neighborhood in the capital city of Comayagüela were detained by the Honduran police and publicly chided by the executive director of the national risk management system for failing to abide by provisions. There is little evidence that any reporters beyond those believed to have been in contact with infected members of the community were detained. However, the emergency declaration remains a concerning novelty as it removes constitutional protection vital for journalists to operate freely. Meanwhile in Bolivia, the government issued an emergency decree that levies criminal penalties against “individuals who incite non-compliance with this decree or misinform or cause uncertainty to the population.” Following the adoption of the decree, Interior Minister Arturo Murillo warned that the government had deployed “cyber patrols” to stop those, including politicians, seeking to misinform about the virus.

On March 11, the Indian federal government invoked the Disaster Management Act, under which any false claim is punishable with up to two years imprisonment and a fine, or both. State leaders also warned of penalties for spreading COVID-19 misinformation as Home Minister Anil Deshmukh Maharashtra stated that those caught spreading rumors could be charged with cybercrimes. Since then, local authorities in India have arrested multiple individuals in connection with allegations of spreading false information. In Golamunda, Kalahani district, a schoolteacher was arrested for posting rumors about a local infected youth. Similarly, a health worker in Dausa, Rajasthan was arrested for spreading similar rumors about local infections. In total, India has arrested over 100 individuals in connection with allegations of spreading false information making India one of the most aggressive examples of a democratic state prosecuting the spread of false information.

South Africa has passed similar measures to stem the proliferation of COVID-19 misinformation in declaring a State of Disaster. Whether spread via traditional or social media, it is now illegal to publish any statement that intends to deceive people about the virus, a person’s infection status, or “any measure taken by the government to address COVID19.” In South Africa, several people have been arrested in connection with violations of the new set of emergency laws for spreading false information. Television personality Somizi Mhlongo turned himself in to South African police after calls from officials for his arrest in connection with Somizi’s claims on Instagram that South African Minister of Transport, Fikile Mbalula, had secretly told him that South Africa’s lockdown would be extended. In a more stringent case, conspiracy theorist Stephen Birch was arrested by police for posting a video “warning” South Africans not to trust government-provided COVID-19 test kits. Thus far, South Africa has arrested at least eight people for spreading false information in an approach that can be characterized as seeking to prosecute in an abundance of caution.

Similarly, democratic states in Asia have adopted legal frameworks which criminalize the spread of COVID-19 misinformation and disinformation. Taiwan has taken some positive steps to combat COVID-19 misinformation, such as establishing the Taiwan Fact Check Center. President Tsai Ing-Wen reminded citizens that spreading false information about COVID-19 could result in a fine or up to three years in prison, as Article 63 of Taiwan’s Communicable Disease Control Act prohibits rumors or incorrect information concerning epidemic conditions of communicable diseases.

The European Union has seen large contrasts in how member countries are responding to the infodemic. In Hungary, where the Orban government has systematically attacked media independence, lawmakers passed a package of amendments to the country’s penal code that extends a state of emergency due to COVID-19 indefinitely and includes prison sentences of up to three years for those convicted of spreading falsehoods about the virus that are “alarming or agitating [to] a large group of people,” and would impose prison terms of up to five years for those convicted of spreading a falsehood or “distorted truth” that has negative repercussions for public health.

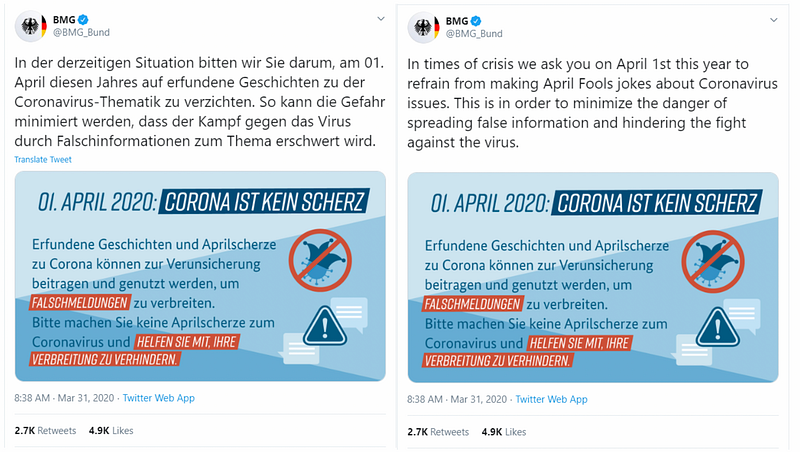

In other countries within the European Union, some democracies have stopped short of criminalizing COVID-19 misinformation but have directly asked their citizens to refrain from joking and spreading misinformation about the virus. The German Health Ministry asked citizens in a tweet to refrain from joking about COVID-19 on April Fool’s Day. Bulgaria’s Law on Measures and Actions in the State of Emergency nearly included criminal sanctions for spreading false information about contagious diseases, but this provision was removed prior to adoption.

Reflecting on the currently implemented emergency measures and novel legislation on criminalizing misinformation, there are two important areas where governments could be better served by amending their approaches. First, most emergency measures do not actually give a definition for what constitutes misinformation, disinformation, rumor, or falsehood. This is a major fault that leaves prosecutors with a wide latitude for interpreting the actions of defendants. Second, many of these measures do not have any sunset clause implemented in their language that would serve to limit the scope of these restrictions. Recognizing that the duration of the pandemic remains uncertain, increased transparency as to when emergency measures will expire or be up for renewal would help to install a check to government power and reassure citizens who may fear their permanency.

Ultimately, governments could seek alternate avenues to combat the infodemic because, quite simply, it is not imperative to criminalize speech to stem the spread of mis- and disinformation. Promoting independent fact-checking organizations, as well as communicating trustworthy information directly and clearly with citizens, would be helpful measures to amplify reliable information about COVID19.

The new measures passed by governments should be encouraged for attempting to seriously discourage and penalize pervasive disinformation. However, it is important to continue putting pressure on governments to do so proportionately and in ways that do not erode fundamental human rights. In trying to strengthen global efforts to combat COVID-19 and the infodemic, it is important that we preserve that which makes our societies resilient.

Jacqueline Malaret and John Chrobak are interns with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.