Cyber-enabled disinformation campaign targeted U.S.-Poland alliance

Polish authorities point finger at Russia

Cyber-enabled disinformation campaign targeted U.S.-Poland alliance

Polish authorities point finger at Russia over April 2020 cyber disruption that planted forged documents and news articles

Poland was targeted by a sophisticated disinformation operation entailing a cyber disruption aiming to damage the relationship between Poland and the United States. Although the Polish government has not presented technical evidence or intelligence data to attribute the disruption to specific actors, the country’s Minister-Special Services spokesperson argued that this particular operation corresponds to Russia’s broader disinformation activities in Poland.

In light of the Kremlin’s assertive foreign policy in the post-Soviet space, Poland sees Russia as an “existential threat” to its security; Warsaw seeks to boost military ties with the United States to counterbalance Russian threat. However, the growing military cooperation between the U.S. and Poland is perceived as a threat by the Kremlin, which strives to undermine the alliance. Against this backdrop, the timing of the cyber-attack is notable: since March 2020, Poland has been hosting several thousand American soldiers as a part of the Defender Europe 20 military exercises, with major activities planned throughout June 2020. Although Defender Europe 20 was slated to be “the largest deployment of U.S.-based forces to Europe in the more than 25 years,” NATO reduced the size of trainings and rolled back some of the activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Long before the outbreak, however, Russia denounced the Defender Europe 20 military exercises along its western border, calling it a destabilizing factor in the region.

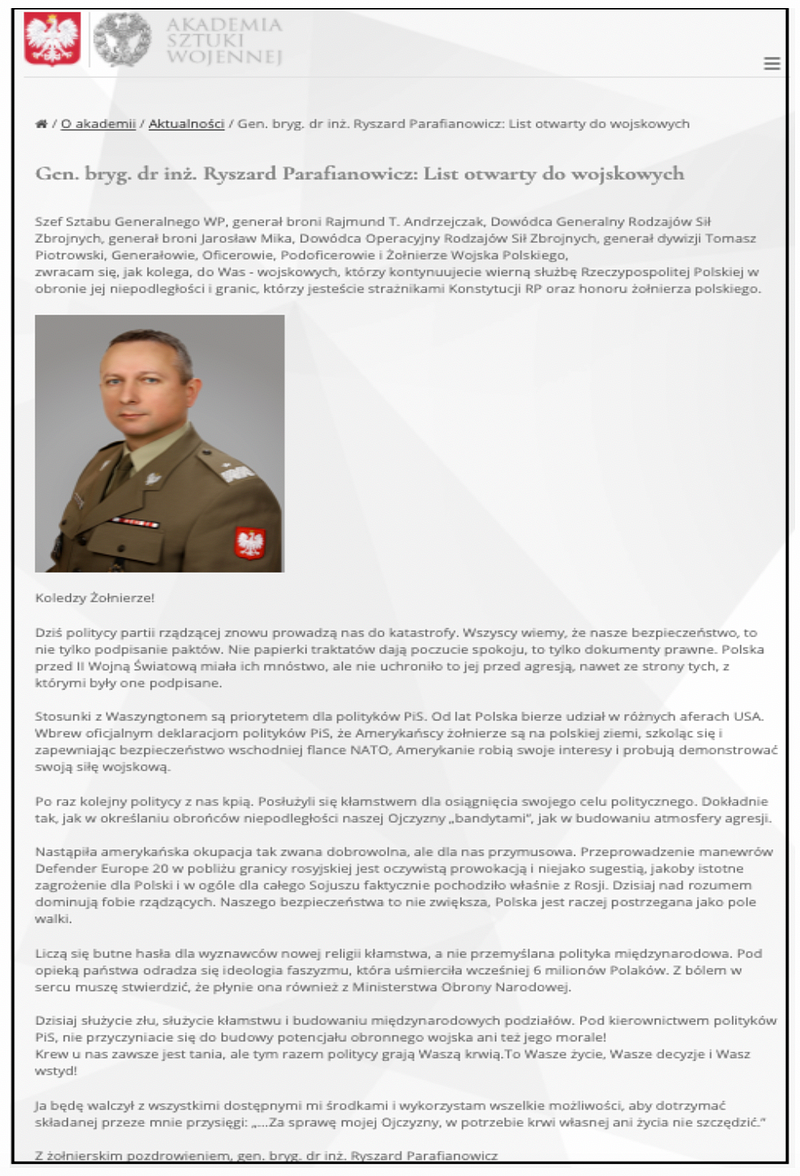

On April 22, 2020, hackers compromised the Polish War Studies Academy (WSA) website and replaced preexisting content with a fabricated letter, allegedly written by the Polish General Ryszard Parafianowicz. The forged letter condemned the “occupation of Poland” by the U.S. and called for Polish soldiers to fight against it. Subsequently, emails were sent to various Polish and international institutions asking recipients to comment on the general’s letter. Hackers also replaced archival articles on Polish outlets Prawy.pl and Lewy.pl with articles containing the fake letter. According to a Minister-Special Services spokesperson, the key objective of this operation was to ignite anti-U.S. sentiments in Poland.

Attribution of any cyber-attack has three main aspects — technical, geopolitical, and intelligence data. The DFRLab requested technical details of the attack from the Polish authorities but did not receive information from them, as the intelligence data is not publicly available. Nevertheless, the DFRLab sought to find out whether the geopolitical component could be used to validate the overall attribution process of this specific attack to Russia by reviewing the Kremlin’s narratives against Poland and drawing parallels with previous cyber-attacks targeting Poland.

The overall context of an attack and past experiences

Russia has a long track record of launching cyber-disruption operations against other countries. Consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton recently analyzed more than 200 Russian-led cyber incidents between 2004–2019 in order to explore the logic behind the country’s cyber operations. The study revealed explicit connections between Russia’s cyber activities and its effort to counter external circumstances that are perceived to threaten Russian military security. Russia’s response to such circumstances are not always military, though. In line with its hybrid warfare operational concept, the Kremlin often opts for a non-kinetic, informational measures as a means of shaping the social and political environment of its adversaries with limited risk of escalation. The Kremlin believes that such non-military measures can also be effective to achieve its regional security goals. As Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov vowed in February 2020, Russia “was not going to ignore the Defender Europe military exercises“ and would “react in a way that will not create unnecessary risks,” while also stressing “everything that we [Russia] do in response to NATO’s threats to our security we do exclusively on our own territory.”

The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation published in 2014 defines deployment of foreign military force adjacent to Russia as an external military risk, which can create conditions for armed conflict. Russia sees Defender Europe 20 as a military risk since the deployment of the U.S. military troops in Poland contains a risk of counterweighting Russia’s Kaliningrad exclave.

In the past, similar activities triggered the Kremlin’s cyber responses targeting Poland. After Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in 2014, NATO Supreme Allied Commander in Europe Philip Breedlove proposed expanding the alliance’s base in the Polish city of Szczecin. Shortly after his announcement, the cyber-espionage group Sednit, connected to Russia’s Main Intelligence Unit (GRU), attacked Polish websites managed by financial institutions and distributed malware into the system. In May 2018, the Polish Ministry of Defense announced the country’s plan to build a permanent U.S. military base in Poland, and it was followed by NATO’s Saber Strike military exercises in Poland, Latvia, and Lithuania. Moscow openly expressed concerns about the military drills, and GRU-linked actors spear-phished Polish government entities, including its Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and distributed malware hosted on Poland’s Finance Ministry website.

These examples show that military exercises of foreign actors near Russia’s border sometimes lead to state-linked cyber activities. It also supports the argument that Russian actors may have been interested in orchestrating the latest cyber-disruption against Poland amid the Defender Europe 20 trainings.

The April hack

On April 22, hackers compromised the War Studies Academy content management system and replaced preexisting content on the website with a fake letter allegedly written by the Polish Brigadier General Ryszard Parafianowicz. The letter criticized the ruling Law and Justice Party (PiS) for participating “in various U.S. scandals” and called the presence of the U.S. troops on Polish soil a “so-called voluntary” but in fact “a forced […] occupation.”

Although the WSA functions under the auspices of the Polish Ministry of National Defense, the incident did not affect the functioning of the ministry’s IT infrastructure nor its data processing.

Stanislaw Zaryn, a spokesperson for Poland’s Minister-Special Services Coordinator, stated that this specific disinformation attack was “congruent with disinformation activities carried out by the Russian Federation against Poland.”

Analyzing the attack

The DFRLab analyzed key narratives mentioned in the fabricated letter and compared them with those circulated in Kremlin-funded Russian media about Poland.

The fake letter contained several false narratives. The first stated “we [Poles] are under American so-called voluntary occupation which is, in fact, a forced one.” Pro-Kremlin actors frequently denounce presence of U.S. troops in Europe, and Russian propaganda actively seeks to trigger negative feelings among Europeans toward American military personnel deployed to the continent. Additionally, the DFRLab found several instances of Kremlin-funded media calling U.S. troops in Poland “occupants.” Indeed, a 2018 Ria Novosti article claimed that the establishment of the U.S. military bases in Poland amounted to a soft occupation. According to the article, Poland became the main foothold for the U.S. Army, which would allow Washington to occupy the entirety of Eastern Europe. Another Ria Novosti article quoted Russian State Duma Deputy Alexander Sherin, who asserted that the plan to build “Fort Trump” in Poland showcases that the U.S. president is the actual leader in Poland, and the fort itself would be a symbol of this occupation. Along similar lines, in 2019, Gazeta.ru claimed that by inviting American troops to the country, Poland committed an act of voluntary occupation.

All of these statements are crafted to undermine relations between the U.S. and Poland. Poland is the closest ally of the United States in Eastern Europe, and the two countries actively cooperate in various fields, such as security, international organizations, and the economy. Poland is also the leading trade partner for the United States in the region, and the United States is Poland’s top non-EU investor. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine was a wake-up call for Poland to seek higher security guarantees from its NATO partners. Therefore, the U.S. military presence in Poland is not a symbol of occupation, but the reassurance of NATO support to the country amid heightened security concerns over Russia’s assertive activities in its neighboring countries.

Another claim made by the fabricated letter was that “carrying out Defender Europe 20 maneuvers near the Russian border is an obvious provocation.” Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs called Defender Europe 20 trainings an “aggressive act,” which can trigger further tensions in international politics. Along similar lines, Kremlin-funded RT dubbed Defender Europe 20 a “provocation against Russia” and asserted that the largest U.S. exercises in Europe in 25 years would deteriorate the security situation of the region. The article went so far as to suggest that the exercise has nothing to do with ensuring security in Europe and that its sole purpose was to irritate Russia. Sputnik asserted that massive deployment of the U.S. Army to a peaceful and prosperous Europe was a “planned provocation.” Another Sputnik article suggested that, although Russia is not explicitly mentioned as a target of Defender Europe 20, the anti-Russian theme of the maneuver is no secret to anyone.

Poland, meanwhile, invited Russia to send its representatives to observe the Defender Europe 20 military exercises — an invitation that Moscow declined because accepting would inconveniently complicate its narrative of being the target of the exercise.

The article also suggested that “the phobic disposition of the Polish leaders dominates common sense. This does not promote Poland’s security; our country is rather perceived as a battlefield.” Pro-Kremlin actors have voiced similar claims many times in the past. Vladimir Dzhabarov, Deputy Chairman of Russia’s Federation Council Committee on Foreign Affairs, taunted Poland for wanting to be a “U.S. military base” rather than a “normal” country. In the same vein, pro-Kremlin media outlet Tsargrad “uncovered” a U.S. plan allegedly to turn Poland into “the main anti-Russia Shepherd dog” in Eastern Europe ready to fulfill any command from Washington.

Kremlin actors routinely disparage governments that choose a closer partnership with the West. This is especially true in case of the former Soviet republics and satellite states. For example, Russia has questioned Ukraine’s right to existence as an independent country and calls Georgia the “colony of the West.” Similarly, Moscow has lamented that Poland is no longer under its sphere of influence and chose to align itself with the “rotten West.”

Hackers distributed the fake letter by publishing it on various news websites

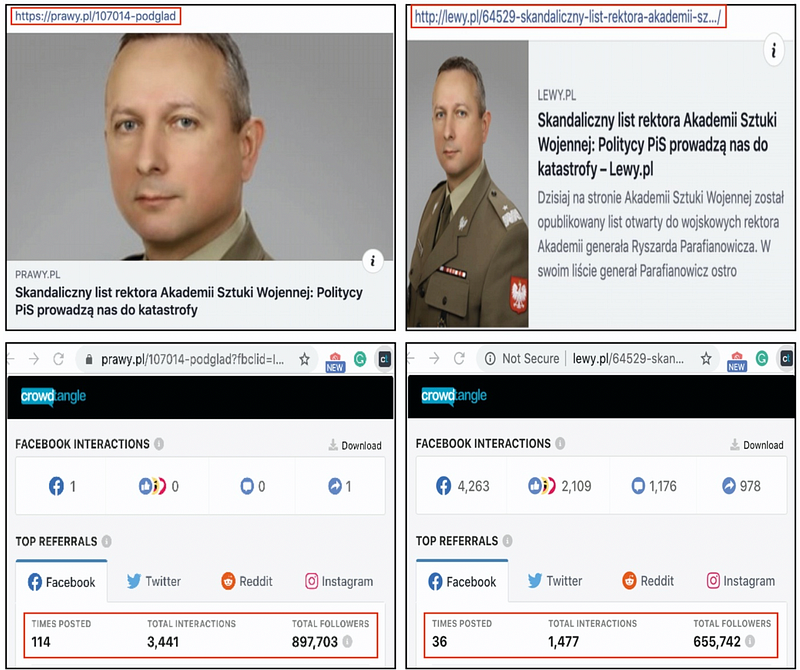

After the fake letter appeared on the WSA website, articles with the headline “Scandalous letter from the Rector of the Martial Arts Academy: PiS politicians lead us to disaster” were published on the websites of two conservative Polish outlets, Prawy.pl and Lewy.pl. Remarkably, both articles were posted retrospectively; the Lewy.pl article was back-dated to February 2019, the one on Prawy.pl was back-dated to February 2020. Editors of both outlets denied that their editorial teams published the articles.

As it turned out, both websites were compromised, as hackers had replaced the old content with articles containing the fake letter.

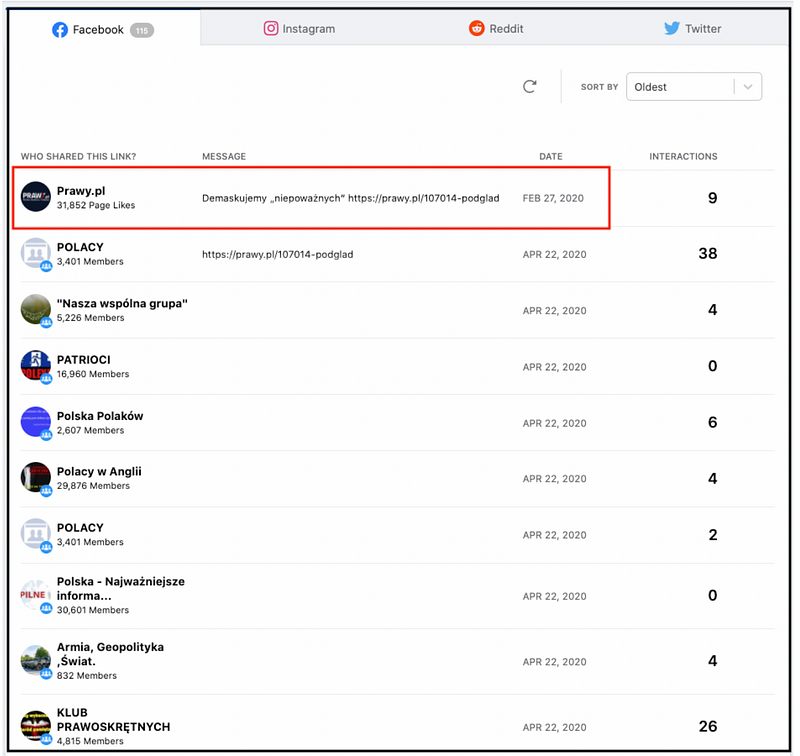

The DFRLab used CrowdTangle to check the spread of Prawy.pl and Lewy.pl articles on Facebook and found that multiple users worked actively to post articles in various Facebook groups before they were removed. A CrowdTangle analysis showed that the article published on Prawy.pl was posted 114 times and garnered almost 3,500 interactions, and the article published on Lewy.pl was posted 36 times with total interactions of nearly 1,500. This leaves the impression that disseminating a fabricated article in social media was a part of the cyber-disruption operation.

Moreover, the CrowdTangle search showed a link to the old article on Prawy.pl, which hackers had replaced with the fabricated letter, was posted on Prawy.pl’s Facebook page on February 27, 2020. After hackers replaced it, the new content was available through the old link, which the hackers used to post the letter to numerous Facebook groups.

The articles also appeared in two other Polish news sites, ono24.info and Podlasie 24, as well as English-language site The Duran. The Duran is registered in Cyprus, and its director, Peter Lavelle, hosts a political talk show at Kremlin-funded RT. The Duran has previously published false information, and its coverage is heavily pro-Kremlin. The DFRLab could not confirm whether The Duran published an English version of the article intentionally or whether hackers also compromised its website.

DFRLab analysis showed the cyber disruption and Russia’s longstanding disinformation efforts against Poland share a number of similarities. This specific cyber-attack is being taken seriously by Polish authorities since hackers managed to compromise the WSA website, formally operating under the Ministry of National Defense. It is possible that malicious actors were testing the resilience of the cybersecurity system of strategic state institutions, with the aim of causing more harm in future. Taking into consideration the specific circumstances in which two previous and latest cyber-attacks against Poland took place, though, Polish authorities should hopefully be able to better anticipate when and how adversaries might launch similar disruptions in the future.

Givi Gigitashvili is Research Assistant, Caucasus, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab and is based in Georgia.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.