Arabic and Persian-language communities amplified pro-Trump disinformation to a new audience

By Simin Kargar and Zarine Kharazian

The 2020 U.S. elections cycle showed that election-related disinformation was significantly homegrown: while foreign interference in various forms proved to be a real threat, the amount of disinformation produced by the domestic far-right media ecosystem, populated by fringe media and personalities often catapulted to the mainstream via President Trump’s now-deleted Twitter feed, far outweighed the apparent impact of content produced by foreign state actors.

But while foreign actors rarely produced original disinformation narratives targeting the U.S. elections in 2020, they did opportunistically seize on existing ones, recycling and localizing disinformation to suit their strategic interests. In the Middle East, as then-President Trump trailed in the polls, pro-Saudi and anti-Iranian government voices feared the loss of an ally in the White House, launching campaigns on Twitter to resurrect an old controversy about former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s emails and preemptively amplify messages of electoral fraud on the part of then-candidate Joe Biden.

These campaigns illustrate the synergies between U.S. domestic and foreign disinformation ecosystems. In addition, the involvement of Iranian opposition groups, notably Restart, in amplifying claims of electoral fraud demonstrates the role of foreign non-state actors in amplifying disinformation campaigns, and the extent to which unsubstantiated claims of electoral fraud in the United States became a topic of global conversation and attracted a range of opportunistic actors in the Middle East.

The “Hillary’s emails” controversy

The 2015 revelation about former Secretary of State Clinton using a personal email server while in office prompted extensive media obsession that continued through the 2016 presidential election cycle and led to several congressional hearings, as well as FBI and State Department investigations, which concluded no compelling evidence of systemic, deliberate mishandling of classified information.

In the run-up to the 2020 election, the release of declassified CIA documents revived the Hillary’s email controversy once again. Among these documents were heavily redacted notes of former CIA director John Brennan suggesting that he had briefed former President Barack Obama on Hillary Clinton’s alleged attempt to link Trump, then the 2016 Republican presidential candidate, to Russia. The attempt was allegedly “a means of distracting the public from her use of a private email server” ahead of the 2016 general election. The move was interpreted as political, seeking to bolster President Trump’s claims that former Obama administration officials conspired to fabricate connections between his campaign and Russia.

Following the announcement, Trump took to Twitter with provocative messages, calling for consequences for his rivals, including former president Barack Obama, Democratic candidate Joe Biden, and former Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton for launching a “coup” against his administration. His tweets sparked a wave of disinformation by his supporters, condemning the “Russia hoax” and asking for an investigation into the ‘real’ matter — i.e. Hillary’s emails.

These narratives were not limited to the United States, however. They were quickly adopted by Arabic and Persian-language echo chambers that were already primed to pivot and disseminate these allegations to undermine the credibility and integrity of Trump’s Democratic rival, Joe Biden, and the Democratic Party more broadly.

Pre-election disinformation

The Twitter campaigns in Arabic and Persian languages claimed new “revelations” about Clinton’s communications that supposedly exposed the scope of the Obama administration’s “corruption” in their dealings in the Middle East. In particular, these campaigns sought to revive conspiracy theories about U.S. support under Obama for the Islamic State (ISIS) and other terrorist groups across the region. The purveyors of the disinformation claimed that the new information substantiated what the rumors had suggested for years.

It started with mostly pro-Saudi accounts on Twitter. Reiterating outdated conspiracy theories about the United States’ role in instigating the Arab Spring, they blamed then-Secretary Clinton for provoking domestic proxies against the kingdom and Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS). Boasting MBS’s ability to dodge those threats, pro-Saudi influencers claimed — without evidence — that “newly leaked” Hillary emails proved her involvement in the smear campaigns and domestic unrest inside the kingdom.

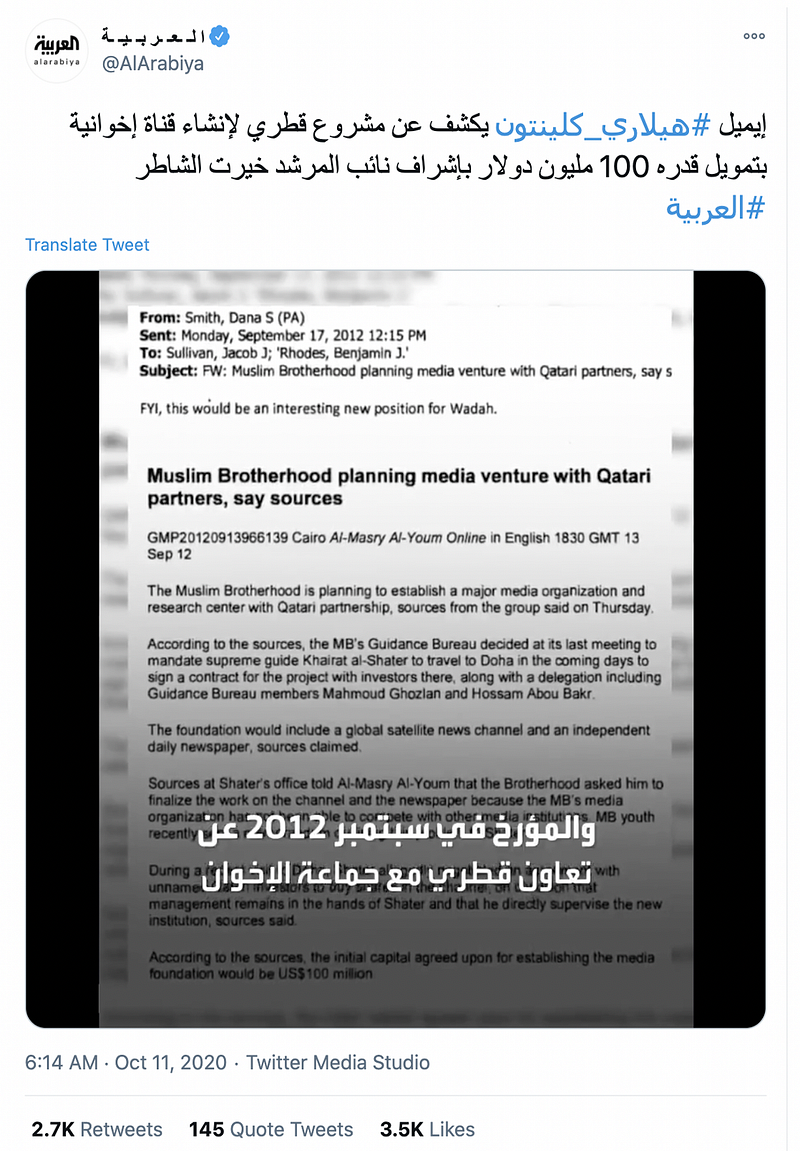

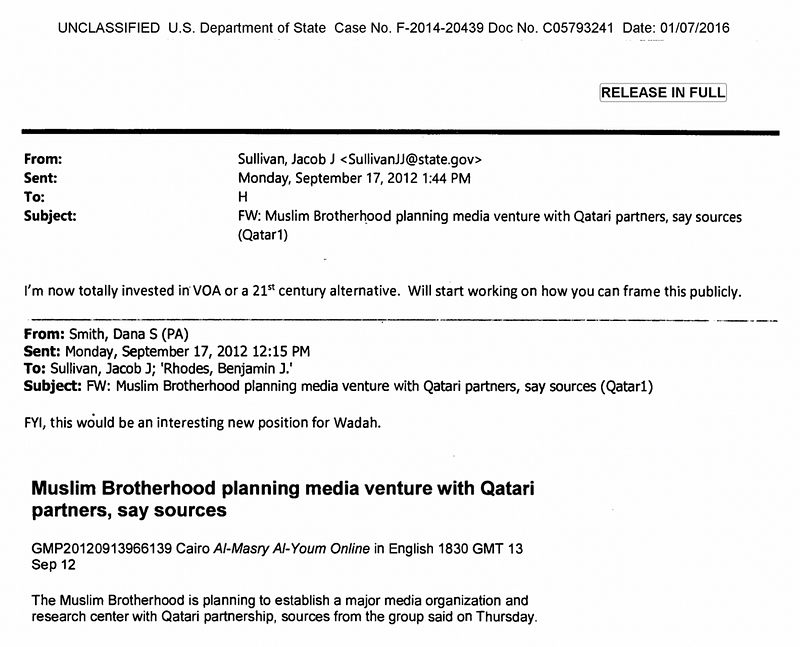

Then, Al Arabiya, a Saudi-owned television news channel, stepped in, capitalizing on the public attention that these allegations were harvesting. On October 11, 2020, Al Arabiya aired a segment in Arabic that claimed “newly leaked” documents showed that then-Secretary Clinton was aware of the support of Qatari partners for a Muslim Brotherhood satellite channel, suggesting U.S. backing of the group. According to these “revelations,” Qatar had invested over $100 million in a new media platform to be administered by Khairat al-Shater, the Deputy Supreme Guide of Muslim Brotherhood. The allegations spread quickly on social media. In particular, pro-Saudi and pro-Emirati governments influencers such as @fdeet_alnssr and @AlraisiSaeed amplified the purported leaked documents, blaming the Obama administration for the supposed coverup. They also seized the opportunity to criticize Al Jazeera, the Qatari-owned news agency, for not covering the “truth” about the alleged revelations.

The email in question was nothing new, however. It contained no secret information and was not even recently released. The unclassified email was already included in the publicly disclosed Hillary emails that have been available since 2016. Moreover, the email thread merely referred to an article published by Egyptian mainstream news outlet Al-Masry Al-Youm Online (also known as Egypt Independent) in English on September 13, 2012. It was supposedly part of regular exchanges about regional developments of interest to Clinton and her high-ranking staff. Jacob Sullivan, longtime Democratic strategist and the incoming national security advisor for President Biden, responded to the thread on September 17, 2012, underscoring his support for U.S. institutions like Voice of America or “a 21st century alternative” in the evolving media and information landscape. But, of course, that part was left out of Al Arabiya’s coverage.

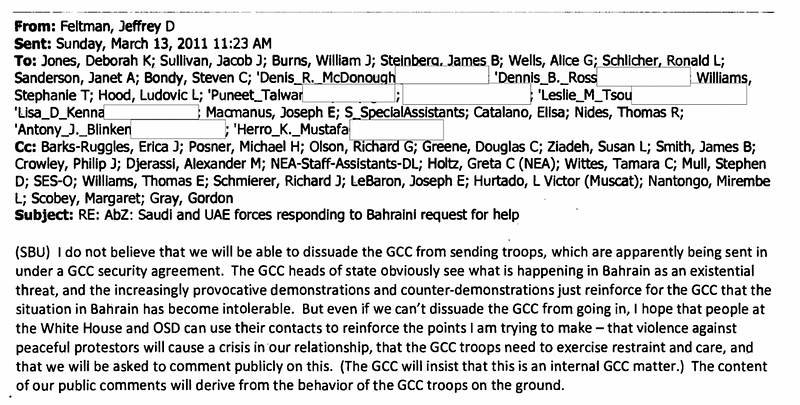

Al Arabiya pushed more claims on the same day. It alleged a rift between then-Secretary Clinton and her Saudi peer, Saud bin Faisal, in 2011, according to yet another newly leaked Hillary email. Al Arabiya claimed that Faisal hung up on Clinton as she urged the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC, which is headed by Saudi Arabia) to revise its decision to send in troops to Bahrain as the Arab Spring reached the country. The request was purportedly interpreted as interventionist and reinforced Saudi’s suspicions that the Obama administration was supportive of toppling Gulf state autocracies. Al Arabiya also claimed that Clinton compensated for this humiliation by approaching Qatar to expand US support for other fringe terrorist groups across the region — once again laying accusations without providing any evidence.

The email that Al Arabiya referred to was also already included in the Hillary Clinton email archive that was released to the public in 2016. The thread was an exchange among State Department authorities about their exchanges with Saudi, Emirati, and Kuwaiti authorities about the prospect of the Saudi-led intervention in Bahrain and its implications for US-Saudi relations. The particular email in question only mentions Faisal’s intention to call Secretary Clinton to discuss the matter — there is no indication of an actual phone call falling through.

The Clinton emails ‘scandal’ goes to Iran

It did not take too long until the so-called Clinton emails “scandal” reached Iranian opposition groups. Multiple Twitter users close to nationalist and pro-monarchy factions of the opposition (i.e., supporters of the exiled crown prince, Reza Pahlavi) began promoting emails related to Iran’s geopolitics. Much of these tweets left out or tweaked important details included in the emails to portray the Obama administration, which Joe Biden was a key part of, and Democrats as hypocrites and sympathetic to the Iranian regime.

Similar to claims made in the Arabic language, these networks also falsely alleged that these emails were newly released by the State Department. They mostly mirrored the Arabic content. For example, one of the most influential nodes in this campaign, a self-proclaimed libertarian researcher based in Mashhad, Iran, Ali Mosaddeghi (@mosaddeghi_ali), posted a translation of Al Arabiya’s claim about then Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal terminating the phone call with Secretary Clinton. He then went on to praise Faisal’s firm move as a wise one which brought long lasting peace to Bahrain. He also described President Obama as a “criminal” and his foreign policy in the Middle East as fodder to terrorism across the region.

While the Arabic and Persian language communities were distinct, there were several accounts, like @moaaddeghi_ali, that appeared to serve as “bridges” between the two, receiving mentions in both Arabic and Persian.

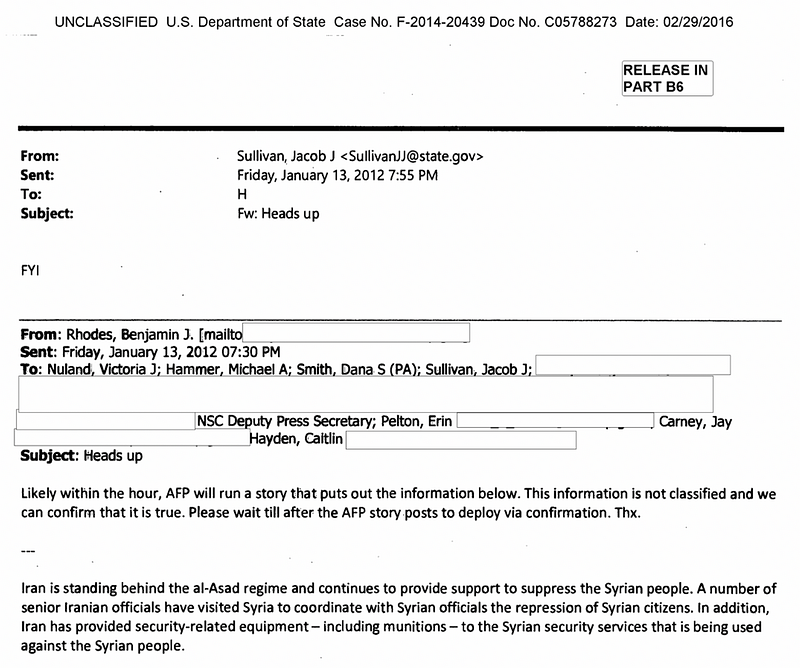

Other users went further in twisting the details regarding Clinton’s emails. They pointed to different analyses and media pieces that were shared with then Secretary Clinton as evidence of her endorsement of the view expressed therein. Take the example of a self-proclaimed Iranian-Canadian-American conservative with an account of Parler — the controversial platform hosting US far-right supporters of President Trump. @nazanin7 referred to an email thread from January 2012, flagging that Agence France-Presse (AFP) was about to disclose Iran’s support for the Assad regime amid the Syrian civil war. The email confirmed that the information was not classified and that the State Department could corroborate it. The email was forwarded to Hillary Clinton as a “FYI” — but that point did not matter to the amplifiers of disinformation.

Iranian pro-monarchy communities were not the only spreaders of disinformation. Restart, a fringe group of Iranian dissidents and adherents to QAnon-style conspiracy theories also participated in the campaign. For instance, without referring to any specific email, they reiterated old unfounded claims that ISIS was ostensibly born out of a collaboration among the Obama administration, Iran’s Quds Force under Major General Qassem Soleimani, and Iraq’s former Prime Minister, Noori al-Maliki.

Since 2016, Restarters have sought to appeal to President Trump and his supporters. They have adopted the slogan “Make Iran Great Again,” (MIGA), a play on Trump’s MAGA or “Make America Great Again”, and have promised a government based on the Cyrus cylinder from 6th century BC and the US Constitution. Restarters frequently reply to the president’s tweets, often using #MAGA together with #MIGA. Restart has received some attention from their far-right peers as well. In an interview with InfoWars, the controversial far-right conspiracy theory platform, Mohamad Hosseini, the self-proclaimed leader of Restart opposition and former entertainment host for Iran’s state-owned television (IRIB) was praised as Donald Trump of Iran.

Restarters amplify claims of electoral fraud

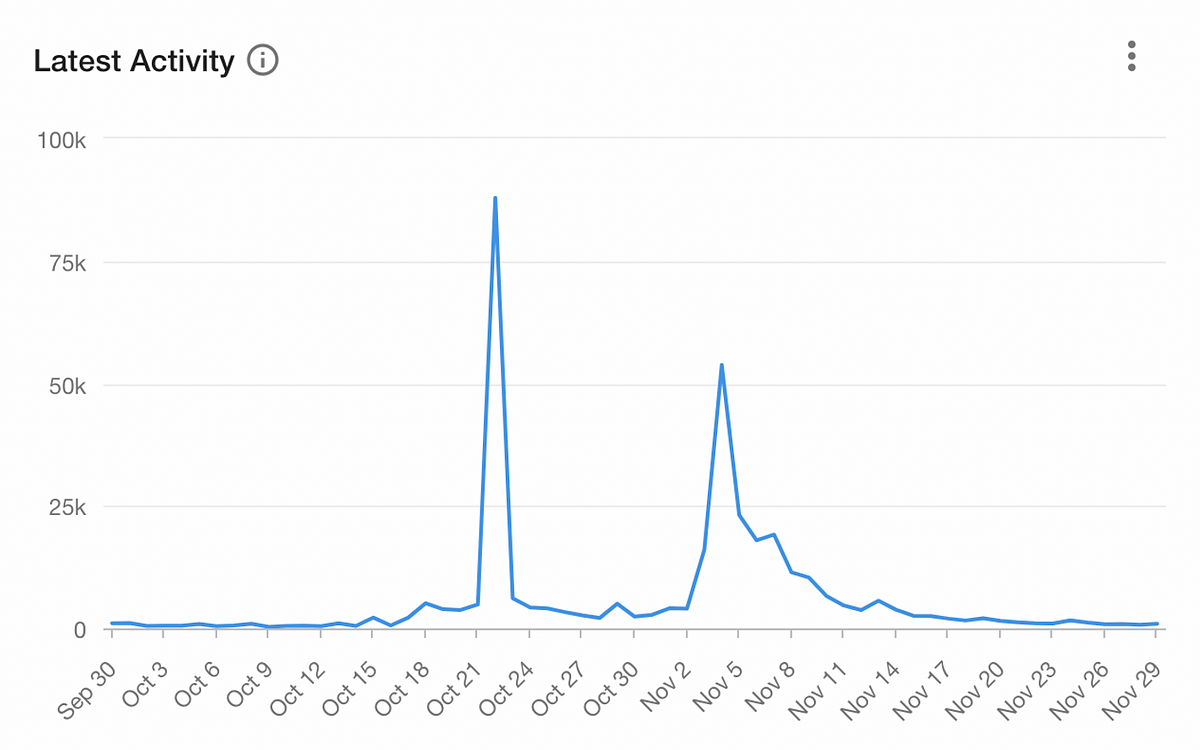

Throughout the 2020 election cycle, Restarters advocated for the reelection of Donald Trump and consistently amplified his false claims on topics such as antifa being a terrorist organization while attacking Joe Biden for his alleged support of terrorism. Their activities peaked on October 23, the day after the last presidential debate, with hashtags #Trump2020 and #Restart_opposition.

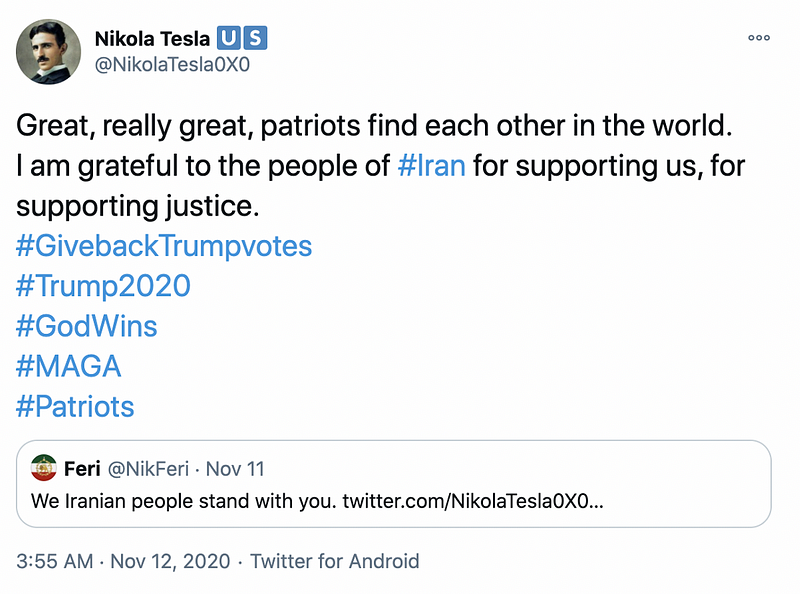

Since election night, when President Trump prematurely claimed victory, Restarters and other Iranian opposition groups, such as pro-monarchists, have insisted that Trump won the election. They have continued to amplify and engage with Trump, other Republican figures, and their MAGA counterparts on Twitter, using the hashtag #StopTheSteal to accuse Democrats of having stolen the election. Their activities were occasionally promoted by Republican figures, such as Georgia representative, Marjorie Taylor Greene, who ran her campaign for Congress on such conspiracy theories as QAnon.

Echoing the MAGA supporters’ tagline, Restarters also populated a fringe hashtag #GiveBackTrumpVotes with pro-Trump messages. Their activities peaked on November 4 and received sporadic praise from the MAGA community as well. Between October 1 and November 30, 2020, Restart alone posted 359,000 tweets, amplifying false claims of election fraud.

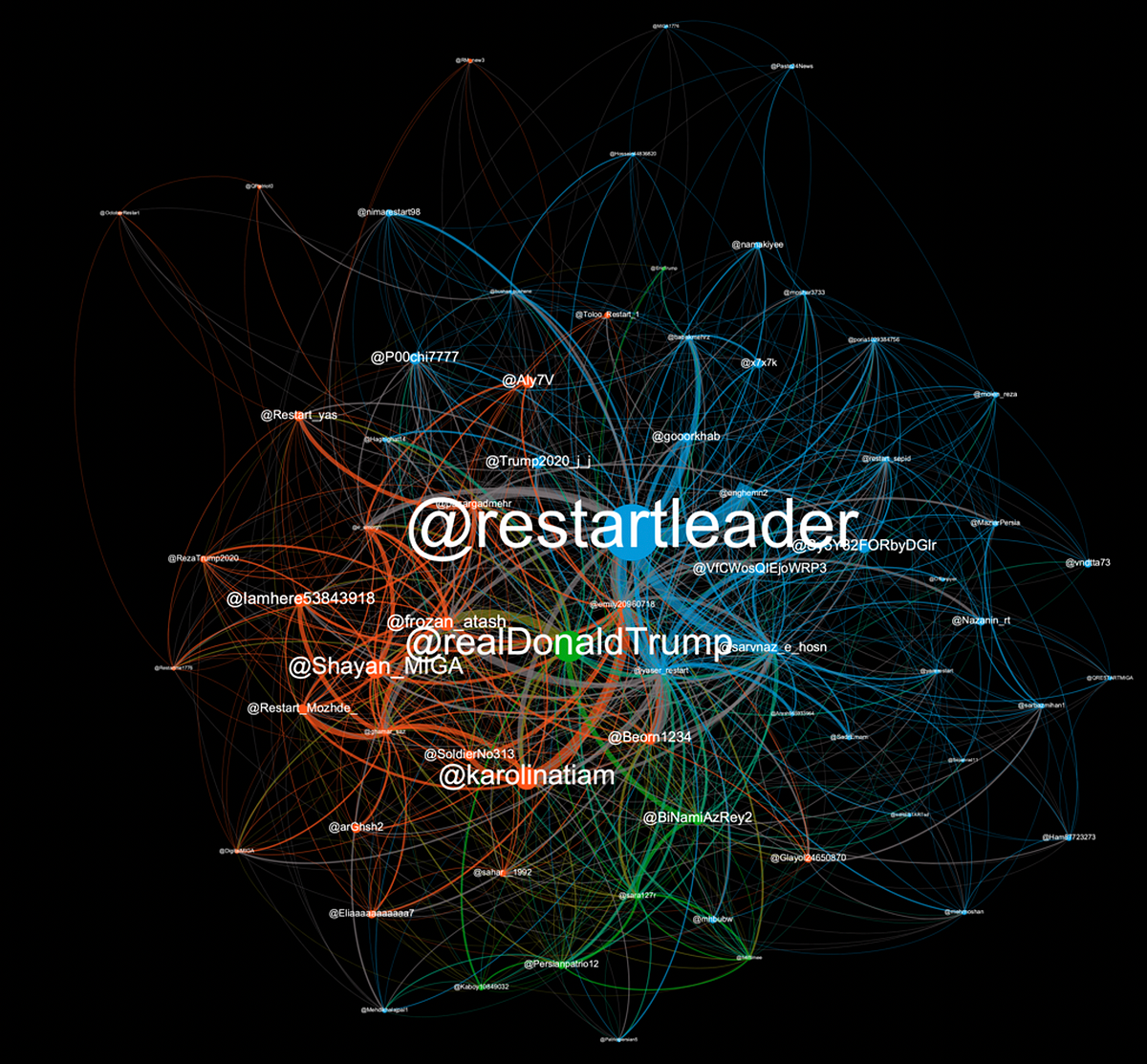

A network of Persian-language tweets alleging U.S. election fraud from October 21 — October 23, 2020 further shows Restart’s role in amplifying pro-Trump disinformation narratives in Persian. During this period, when Iranian opposition groups’ amplification of disinformation about the U.S. election peaked. The primary accounts involved in amplifying these claims were aligned with Restart, and the accounts receiving the most in-links in tweets about electoral fraud in Persian were those of Trump and Restart leader Seyyed Mohammad Hosseini.

Disinformation campaigns are not exclusive to states and their agents. Non-state actors can be equally motivated to weaponize social media and cultivate falsehoods for their strategic interests.

The presidency of Donald Trump, his antagonistic approach toward the Iranian regime, and friendly nudges to Iran’s arch rival, Saudi Arabia, have emboldened multiple non-state actors to manipulate online conversations and maximize their interests. For example, over the past years, several Iranian opposition groups have sought to appeal to the Trump administration and vie for influence over U.S. foreign policy toward the Iranian regime with complaints about human rights abuses or economic mismanagement.

The recent disinformation campaigns about Hillary Clinton’s emails were an attempt by pro-Trump Persian and Arabic-speaking communities to demonize then Democratic candidate, Joe Biden, portraying him as yet another “dangerous” Democratic president for security in the Middle East. To these communities, another term of Trump could have facilitated regime change in Iran and expansive influence for Saudi Arabia and its allies, such as the United Arab Emirates, across the region. By promoting such claims, these non-state actors sought to do their bid in supporting President Trump, as their presumed ally in the White House.

Yet these campaigns had their origins in the political developments in the United States. Incidents such as selectively releasing CIA documents by the Director of National Intelligence unleashed conspiracy theories not only at home but also in other contexts and languages. Across the Middle East, some audiences were already primed for conspiracy theories about the U.S., in part because of the complicated history of U.S. involvement in the region. The new allegations maximized traction and believability by speaking to the existing distrust among some of these communities. Election disinformation campaigns by non-state actors from the Middle East may not have been particularly novel in method and content, but their timing and targets call for closer investigations. They indicate how disinformation travels borders, languages, and contexts. They also underscore how regional media outlets as well as fringe movements can push political narratives that go well beyond their intended local targets, reaching the United States and around the world. Disinformation often starts at home but leaps in many unanticipated directions. The 2020 election season presented no shortage of this trend.

Simin Kargar is a Nonresident Fellow with the Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).

Zarine Kharazian is Associate Editor with the DFRLab.

Cite this case study:

Simin Kargar and Zarine Kharazian, “How US elections disinformation fueled foreign policy falsehoods across the Middle East,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), March 18, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/how-u-s-election-disinfo-fueled-foreign-policy-falsehoods-across-the-middle-east-1d53f4f47734.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.