Following Jovenel Moïse’s assassination, a subset of social media users promoted conspiracy theory around US involvement

By Samantha Delman

In the wake of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse’s July 7, 2021 assassination, a subset of Haitian and international social media users amplified a narrative that the US government allegedly participated in the crime.

While the appearance of conspiracy theories is normal in the absence of evidence-based information during major geopolitical events, when it comes to Haiti and its history of US and international intervention, unfounded online claims can pose a threat to stability in the country as they can add fuel to real-world unrest. While anti-government protests have unsettled the country in recent years, the assassination left no clear successor and resulted in renewed civil unrest and a power vacuum such that two prime ministers, a senator, and a gang leader all claimed power following Moïse’s assassination. Eventually, Prime Minister Claude Joseph, who had been in office since April 14, agreed to step down on July 20 and be replaced by Ariel Henry, whom Moïse had appointed as Joseph’s replacement just two days prior to the assassination.

Local authorities have named Haitian-American Christian Emmanuel Sanon as the mastermind behind the attack, but questions about motive and the operation’s financing remain open, leaving many Haitians skeptical of the official story. The fact that two of the people arrested for the murder were Haitian Americans, and the discovery of prior links between some of the private contractors involved in the assassination with the US Drug Enforcement Agency, also made social media users hesitant to believe that the US government did not play a larger role in the orchestration, organization, or financing of the assassination.

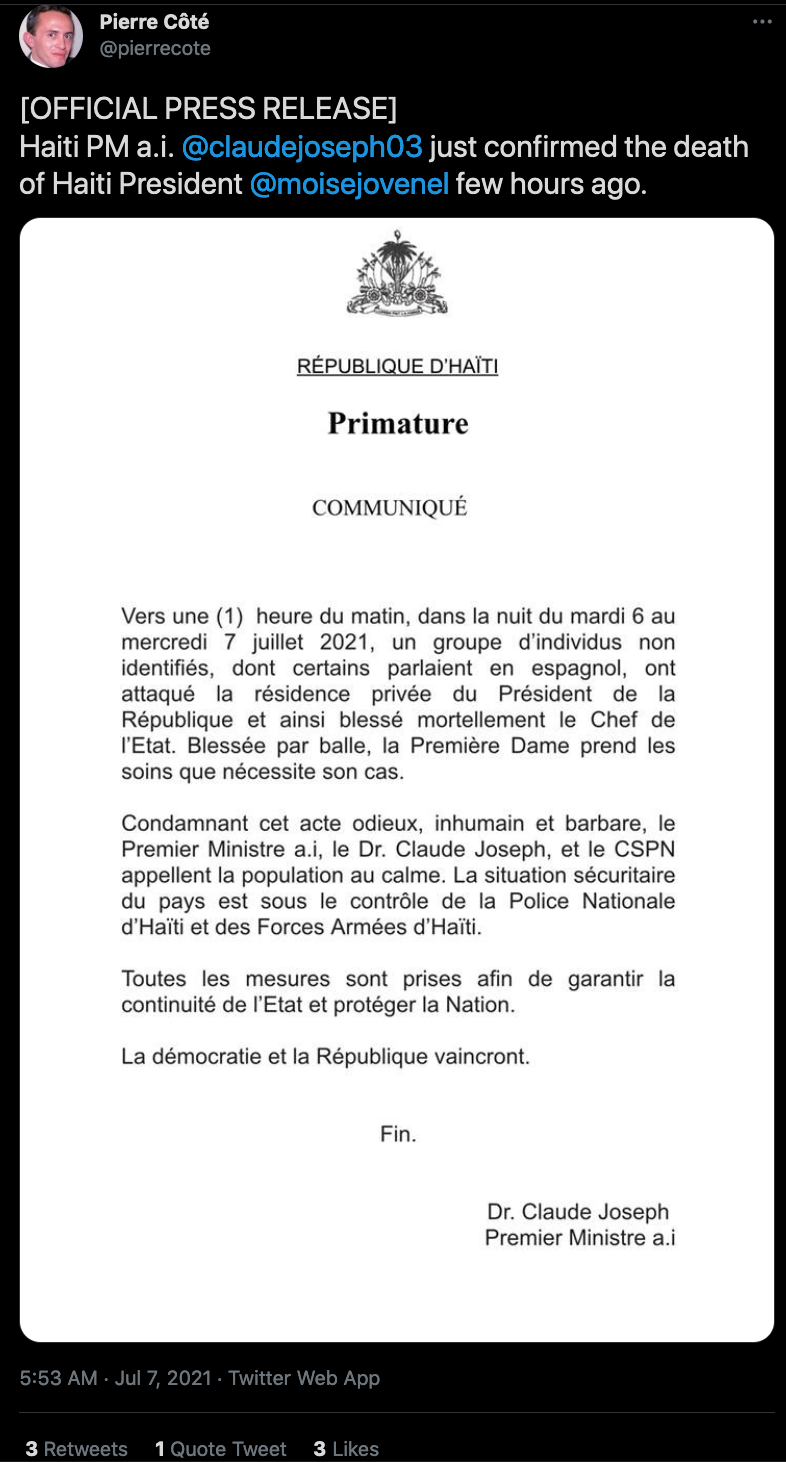

The assassination

According to an official statement released by former Acting Prime Minister Claude Joseph, a group of unidentified attackers infiltrated Moïse’s private residence at approximately 1:00 am local time (5:00 am GMT), killing him and injuring his wife, First Lady Martine Moïse. No members of his security detail were injured or killed in the attack, however, spurring speculation as to their possible involvement.

Moïse was backed by the United States but had become, in the words of US Gregory Meeks (D-NY), “increasingly authoritarian.” Many in Haiti contested his power, leaving behind a long list of enemies, any of which could have had a motive for orchestrating his murder.

After the assassination, the Haitian National Police accused 28 privately contracted individuals — comprised of 26 Colombian mercenaries and two Haitian-American translators — of executing the attack. Seventeen of the 28 individuals under investigation for the assassination have been detained, while three were killed in the pursuit of the suspects, and eight fled successfully.

National Police Chief Leon Charles named a Haitian-American doctor, Christian Emmanuel Sanon as the mastermind behind the attack. Charles claimed that Sanon hired a Miami-based private security firm; he hypothesized that the motive for the assassination was Sanon’s personal political ambitions, citing his past criticism of the corruption around the Haitian government’s use of international relief funds in the wake of the 2010 earthquake, his YouTube video addressing Haitian leadership, and a May 2021 decree from his organization in which he declared that Haiti urgently required a transitional government.

Following Charles’ statement, establishment and mainstream media, including The Daily Beast and The New York Times, were quick to run with the story on Sanon. Police theories and suspect interviews suggested that the mercenaries were originally hired to kidnap Moïse and force his resignation and then to aid Sanon’s peaceful ascent to the presidency in Haiti. Somewhere along the way, however, plans changed, leaving the president dead, sparking civil unrest, and catalyzing a power vacuum in Haitian politics.

Many people, however, expressed skepticism over Sanon’s ability to finance and execute this assassination autonomously. He had previously filed for bankruptcy in 2013, and was an entirely obscure figure in Haitian politics, leaving many online users questioning whether his political ambitions were the true motive behind the attack.

Finally, one of the individuals arrested in relation to the attack was a former DEA informant. Reuters reported that a DEA official wrote in an email, “One of the suspects in the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was a confidential source to the DEA. These individuals were not acting on behalf of DEA.” The official also stated agency had encouraged the former informant to surrender to Haitian police. Moreover, the hired team is said to have entered the private residence of the president disguised as DEA agents and, when arrested, told investigators that it was a “DEA operation.” In addition, a DEA hat was found alongside weaponry in Sanon’s home.

Following then-Prime Minister Claude Joseph’s request for the foreign intervention of troops, the United States responded by sending the FBI and Department of Homeland Security to Haiti to aid in the investigation. Joesph’s call for troops deepened the political divide, as Haitian citizens have advocated for nonintervention following more than a decade of United Nations presence under Operation MINUSTAH.

Social media users and online engagement with conspiracies

Online users have remained skeptical of Sanon’s role and taken to the internet to insinuate the alleged participation of the US government — via the DEA or otherwise — in the assassination.

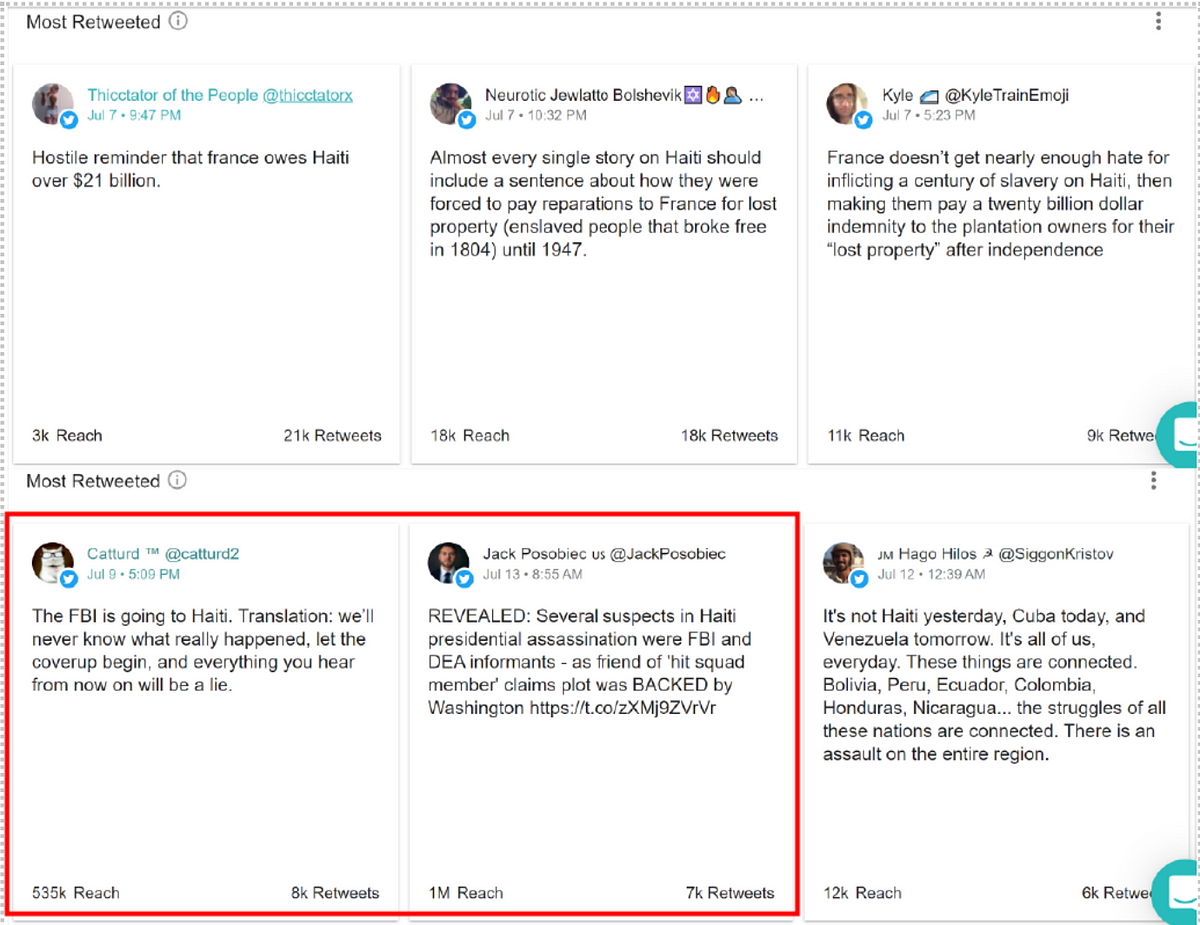

On Twitter, posts that suggested that the US was somehow involved in the plot received substantial engagement — in terms of the number of retweets, they were only behind those that discussed France’s colonial past in Haiti. Using social media monitoring tool Meltwater Explore, the DFRLab queried the most retweeted posts to use the words “Haiti” or “Moïse” in the 30 days between June 20 and July 19, 2021. Among the six most retweeted posts, two mentioned conspiracies regarding US involvement in the assassination, both of which belonged to well-known US right-wing Twitter influencers, far-right conspiracist Jack Posobiec and pseudonymous troll Phillip Buchanan, who operates under the Twitter handle @catturd2. Posts from the two influencers, both of whom have histories of promoting misinformation and conspiracy theories, contributed to broader narratives in pro-Trump communities that seek to undermine confidence in US national security agencies. According to the Meltwater query, the two posts combined reached more than 1.5 million users; Posobiec and Buchanan received 7,000 and 8,000 retweets on their posts, respectively.

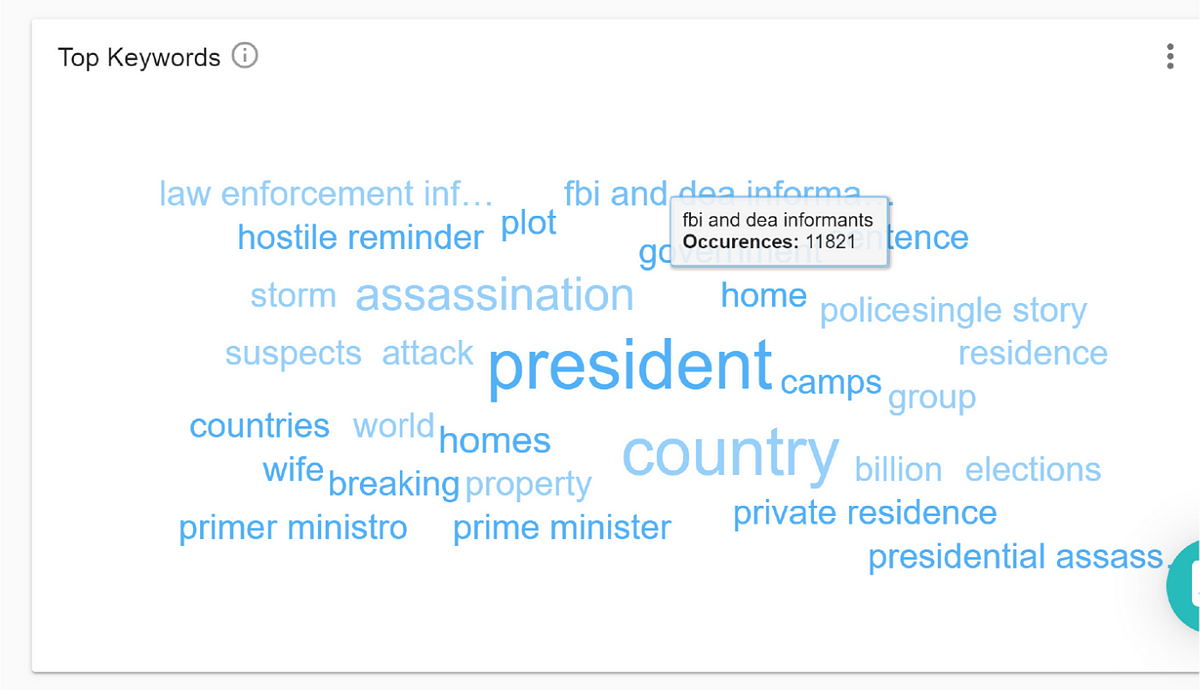

The DFRLab also analyzed the keywords found alongside “Haiti” or “Moïse” in social media posts between June 20 and July 19. A Meltwater Explore query showed that some of the most used words included the phrase “fbi and dea informants.”

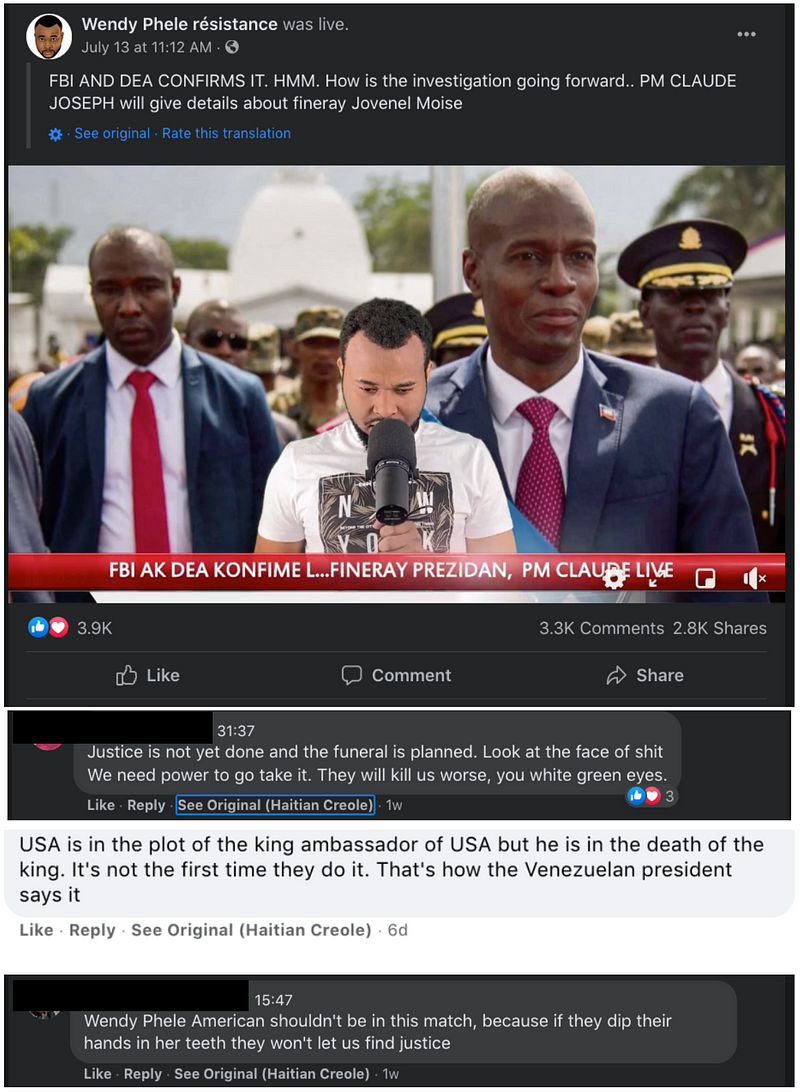

On Facebook, allegations of US involvement appeared mostly in comments to posts, demonstrating that even objectively factual social media posts have been effectively polluted by the conspiracy theories taking hold in their comments sections.

For instance, a livestream by Facebook page “Wendy Phele résistance,” a self-proclaimed human rights advocate, received 3,900 likes and 3,300 comments, many of which emphasized conspiracy theories and a general distrust of the establishment.

One of the commenters used the term “white green eyes,” which seemed to suggest an anti-white or anti-imperialist epithet. Others suggested conspiracies regarding undercover US operations and a negligent investigation to serve as a cover-up, stemming from a long history of US and UN foreign intervention in the region.

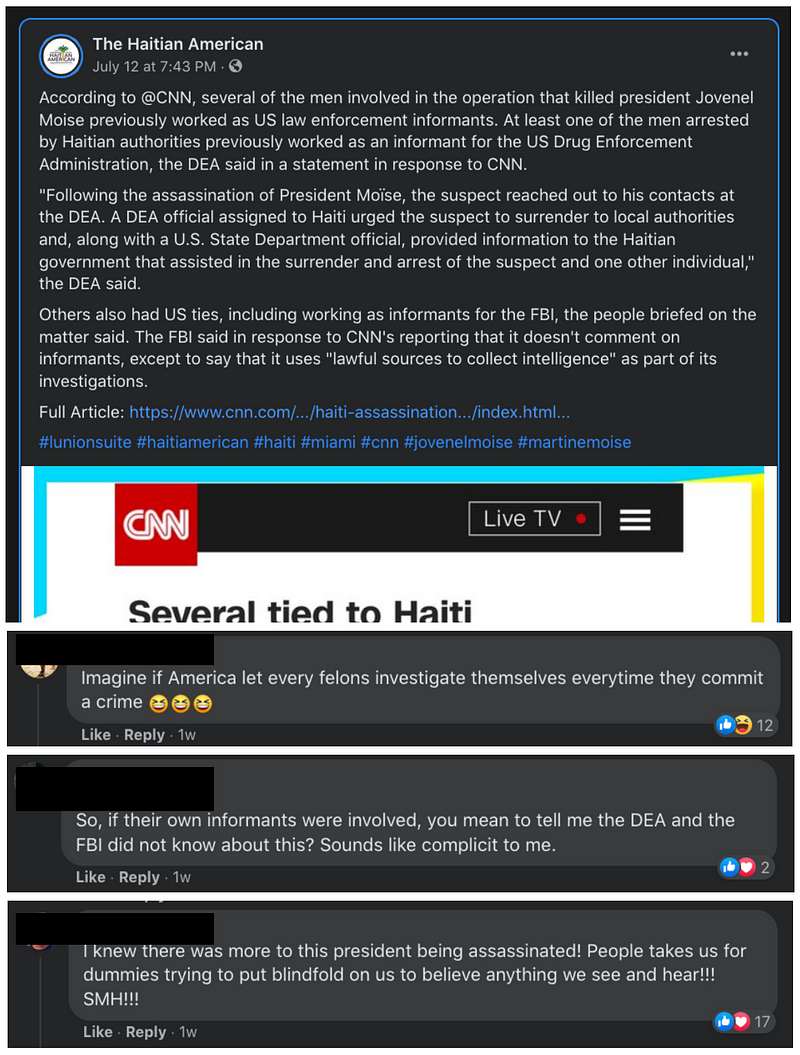

A post to the Facebook page for society and culture website The Haitian American shared a CNN article exposing the suspects’ ties to the US law enforcement community and was similarly met with heavy engagement in the comments section from conspiracy theorists convinced that the United States played a role in the assassination.

The Colombian connection

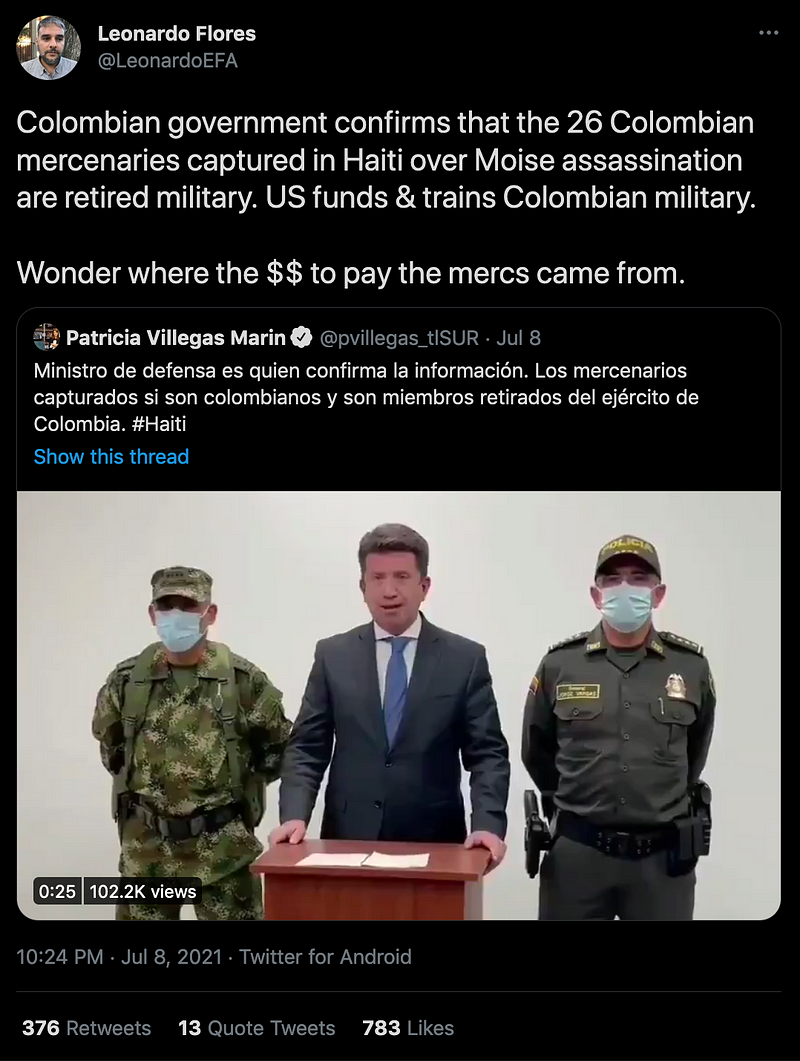

In addition to the DEA connection, both Al Jazeera and Voice of America, among other publications, presented evidence indicating that seven of the Colombian mercenaries hired to orchestrate the assassination received military training in the United States. One Twitter post responding to the Ministry of Defense’s announcement of the mercenaries’ nationality, before even learning of their ties to US military training, insinuated that the relationship between the United States and the Colombian mercenaries was implicit.

Kremlin-funded RT also connected the United States to the Colombian mercenaries. In a video posted to Ahí les Va, RT’s Latin America-focused YouTube channel, presenter Inna Afinogenova compared Moïse’s murder to the failed Operation Gedeon, in which foreign mercenaries attempted to remove Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro from power in 2019. Afinogenova mentioned the participation of Colombian mercenaries on “paramilitary operation in Afghanistan, Iraq, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen” to claim that Colombia is well positioned to be one of the top source of mercenaries for hire in Latin America, and that the United States is the main “business operator through its numerous and euphemistic ‘security firms.’”

As more information comes to light, more questions have been generated than answers. The motive behind the assassination or the financing that funded the mercenaries remain unknown. Additionally, the investigation has yet to prove or disprove the suspicions domestic or foreign involvement.

While no one seems to know the full extent of what happened, a subset of social media users continue to argue that there is more to the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse than current reporting suggests. With so much still unknown, disinformation, conspiracy theories, and conflicting or false narratives are thriving and will likely continue to do so in the weeks and months to come.

Samantha Delman is a research intern with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Cite this case study:

Samantha Delman, “Conspiracy theories emerge in the wake of Haitian president’s assassination,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), July 27, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/conspiracy-theories-emerge-in-the-wake-of-haitian-presidents-assassination-ef1ea914185a.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.