Inauthentic Facebook assets promoted Russian interests in Sudan

Network with links to Russia’s Internet Research Agency promoted oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin and Russian naval presence in Sudan

Inauthentic Facebook assets promoted Russian interests in Sudan

Share this story

From Yevgeny, with love. (Source: Facebook and Reuters/Sergei Ilnitsky/Pool)

On May 27, 2021, Facebook removed a network of assets using inauthentic profiles, pages, and groups to amplify pro-Russian content in Sudan. The content primarily focused on promoting an image of Russia as a friend of the Sudanese people, while simultaneously painting prominent leaders as pawns of the United States. The pages and profiles worked to spread positive stories about Russia, focusing specifically on aid packages sent by Russian oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin and amplifying the benefits of the creation of a Russian military base in Port Sudan.

Facebook attributed the network to individuals previously involved in Prigozhin’s Internet Research Agency, which became notorious for its interference efforts during the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

The pages had a total following of 440,000 individual user accounts. Although only two pages had administrators based in Russia, pages that were administered from Sudan also posted pro-Russian content.

Facebook removed the network of 30 pages, six groups, 83 accounts, and 49 Instagram profiles after an independent researcher tipped off both the DFRLab and the platform about alleged Russian-operated Sudanese pages. The DFRLab had access to 29 pages, six groups, 79 accounts, and 48 Instagram profiles before they were removed by Facebook as part of an ongoing partnership to monitor election interference and identify disinformation spread on the platform.

According to a statement released by Facebook:

The people behind this activity used fake accounts — some of which were already detected and disabled by our automated systems — to post, comment on their own content, and manage Pages and Groups. Some of the accounts used photos likely generated using machine learning techniques like generative adversarial networks (GAN). This network appeared to operate across multiple social media platforms.

They posted in Arabic about pan-African news and current events in the region, including politics in Sudan, tensions in Chad, Ethiopia and Palestine, as well as supportive commentary about the Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and the relief aid initiatives in Sudan by Russian financier Yevgeniy Prigozhin, who was _indicted by the US Justice Department. Most recently, the operation’s posts began to criticize the Health Ministry of Sudan and claim that Prigozhin’s aid is being blocked from entering the country.

We began looking into this campaign after reviewing information about a portion of its activity shared by an independent open source researcher. We found some links between this operation and the network we removed in October 2019. Although the people behind it attempted to conceal their identities and coordination, our investigation found links to individuals associated with past activity by the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA).

This is not the first time Russian-linked content has been identified in Sudan. In 2019, Facebook identified pages associated with entities tied to Prigozhin and his private military company, the Wagner Group. Again in 2020, Stanford Internet Observatory and Graphika analyzed eight pages targeting Sudan that were associated with Russia as part of a larger Russian operation. In both reports, a number of pages presented themselves as “news” pages and posted political content focused on improving Russia’s image. Similarly, for this report, the DFRLab identified pages posing as politicians and news sites, spreading pro-Russian propaganda. Of the 29 pages reviewed by the DFRLab, 11 claimed to be either a politician or media, occasionally copying news content from legitimate websites while primarily promoting Prigozhin and Russia.

Russia’s presence in Africa has steadily increased over the last few years, with the country signing military cooperation agreements with at least 20 African countries. Wagner Group forces specifically were first spotted in Sudan in December 2017, providing training and weapons to the Sudanese armed forces. In 2018, Russian advisers, led by Prigozhin, drew up a program designed to ensure that Sudanese strongman Omar al-Bashir would remain in power and sent private military contractors to bolster al-Bashir’s forces. But in April 2019, despite Russian assistance, al-Bashir was deposed and replaced with a Transitional Military Council (TMC). However, protests that facilitated the ousting of al-Bashir continued, and on June 3, 2019, tensions came to a head as TMC forces, headed by a governmental paramilitary group named the Rapid Support Forces, massacred over 100 unarmed civilians. Russia continued to support the TMC, voting to block a United Nations bid to condemn the killing of civilians.

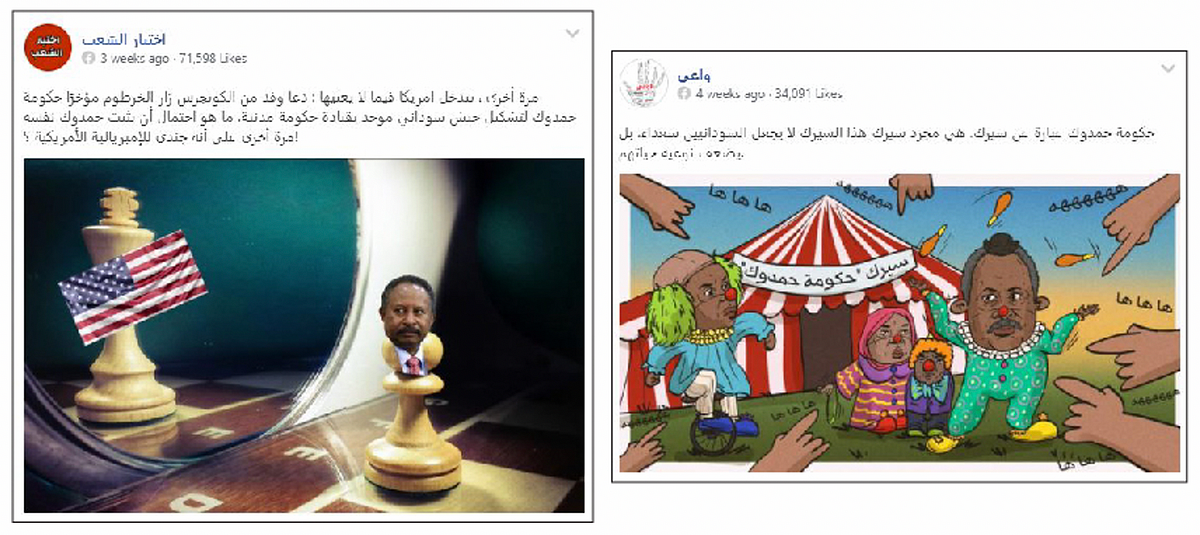

On August 20, 2019, the TMC was replaced by the Sovereign Council, jointly led by military and civilian leaders with Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok at the helm. Hamdok served as Deputy Executive Secretary for the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. As a result of his ties to the UN and the West, the pro-Russian pages depicted him as a Western pawn.

From Yevgeny, with love

In mid-April 2021, Sudan’s news agency SUNA and Russian state media outlet Sputnik Arabic reported that Prigozhin had distributed food baskets to poor communities, with the assistance of Resistance Committees, grassroots organizations that played a major role in the Sudanese Revolution. During the rule of al-Bashir and the demonstrations against him, Prigozhin and his organizations had worked to delegitimize grassroots organizations, such as the Resistance Committees.

The aid was packaged with images of the Russian flag inside a heart, and Arabic text stating “From Russia, with love” and “courtesy of Yevgeny Prigozhin.” The majority of the pages removed by Facebook promoted this act of “humanitarian” support.

These posts were then shared to legitimate Sudanese groups by a small group of inauthentic user accounts whose profiles were removed during the takedown. The accounts consistently liked the Prigozhin and Russian-linked posts and shared them to either their own profiles or other groups.

Most of the pro-Prigozhin posts received only a handful of likes, with the exception of one: on April 10, a page named اختيار الشعب (“The Choice of the People”), labelled as a “News and Media Website” with over 71,000 followers, published a post praising a “Russian businessman” for launching a humanitarian campaign in Khartoum. With 152 reactions and 236 shares, the post performed 14.3 times better than other posts by the page created in the previous month, according to statistics from the Facebook monitoring tool CrowdTangle.

While the content of the post was relatively standard, engagement with it made it an outlier. However, a closer look at the comment sections revealed that the overwhelming majority of comments on the post were made by profiles using stolen images as their profile pictures. In one instance, one of the profiles attacked the Ministry of Health, saying no one was helping the poor. Other inauthentic profiles included in the takedown responded saying the ministry was ineffective, that ministers had fancy cars and lived in nice houses rather than helping the poor, and that Yevgeny Prigozhin was a true friend to Sudan.

On May 20, the pages started posting content claiming additional aid being sent by Prigozhin was being prevented from entering the country by the Ministry of Health, either due to governmental greed or Western influence. The DFRLab could not find any media sources indicating the Ministry of Health was preventing additional aid from entering the country, although a number of other Facebook pages reported that the Ministry prevented aid from entering the country for at least one month.

Confusion over a Russian naval base

On December 8, 2020, Russia and Sudan signed a draft agreement allowing Russian warships, including nuclear-powered ones, to be kept in Port Sudan on the Red Sea. According to the agreement, the base would function as a logistics center and strategic foothold in the region. Officially, it will be used to coordinate fighting piracy in the Red Sea and the region, but its very presence could have broader geopolitical implications as well.

In late April 2021, however, confusion arose over the status of the agreement. On April 28, the official Twitter account of Saudi Arabia-based news organization Al Arabiya claimed that the agreement to establish a naval base had been suspended. Russian media also ran with the story, but, on April 29, the Facebook page for the Russian Embassy in Sudan posted a statement saying the reports did “not correspond to reality.”

Between April 28 and May 3, the pages removed by Facebook posted content relating to the naval base and how beneficial it would be to Sudan. The pages blamed “corrupt authorities” wanting to blackmail Russia for putting a hold on the logistics center.

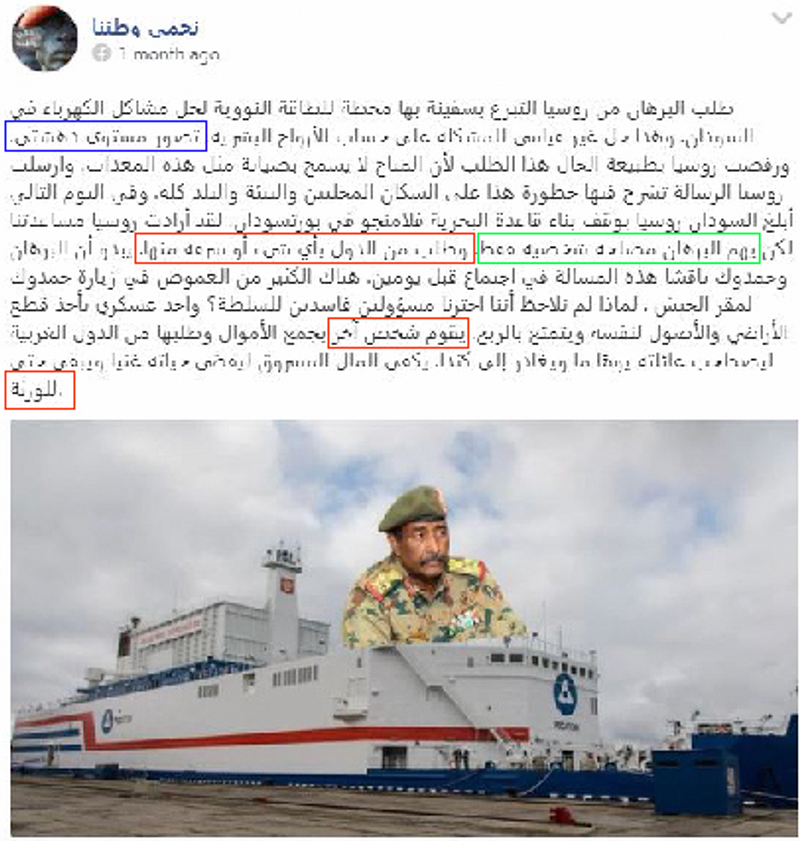

The pages also started posting negative content about of Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman al-Burhan, chairman of the Sovereign Council and previous head of the Transitional Military Council. The pages had previously been supportive of al-Burhan but changed tack after the confusion around the naval agreement. Al Arab later reported that al-Burhan met with a Russian delegation at the time of the confusion and that military cooperation with Russia would be postponed until the formation of a legislative council to ensure Sudan maintains support from the United States. On May 6, Lt. Gen. Mohamed Othman al-Hussein, chief of staff of the Sudanese Army, confirmed that the agreement had not been presented to or approved by parliament, as it had a number of clauses included by the previous regime that could be considered harmful to the country.

The pro-Russian pages started to blame al-Burhan for allegedly ending the agreement, claiming he only had his own interests at heart. From early May onward, the pages continuously posted content lambasting al-Burhan, saying he was corrupt, greedy, and worked for the West.

Edited Russian profile pictures

Many of the images used by the accounts as profile pictures or banner images were taken from the Russian social media platform VKontakte. To make the images unique and thus more difficult to find using a reverse image search, some of the more active profiles cropped the images and flipped them horizontally. The images had also been manipulated to change certain colors without looking overly edited. The DFRLab tried to recreate these edits using image editing software and found it required multiple subtle changes. Most notable, the different images required different edits; in one example, a t-shirt was changed from red to orange, while in another example a long-sleeved shirt was changed from blue to purple. However, neither image was simply lightened, as the skin tones of the people themselves were not always altered substantially.

In other instances, more drastic measures were taken to make it harder for reverse image searches to recognize the images used as profile pictures. One image, again taken from the profile of a VK user, had hair added to it. The image was also flipped, the contrast and blue tones enhanced and the skin smoothed.

As a result of these edits, reverse image searches using Google, Bing, and TinEye did not return results. Only the Russian search engine Yandex was able to identify the edited images, returning results showing the unedited VK profiles.

Anti-government posts

While Facebook noted that posts included narratives supportive of Hamdok, the pages reviewed by the DFRLab appeared to have become more critical of him and members of the Sovereign Council, particularly since the controversy erupted over the proposed Russian naval base. The prime minister was depicted as being supportive of the West as a result of his ties to the UN and his dual British-Sudanese citizenship, with one page depicting him as a literal pawn on a chessboard. The pages blamed him for Sudan’s struggling economy, saying he had failed to fix the country, and that the Sovereign Council acted more like a circus than a government.

Many of the pages that were supportive of the Sudanese military and the Rapid Support Forces for their connections with Russia and the Russian military claimed Hamdok wanted to interfere with the military and bolster the Sudanese armed forces with international soldiers to increase his control, making Sudan dependent on the West for military support. This was presented as a weakening of Sudan’s military, which had previously received support from Russia.

One of the pages that had administrators based in Sudan and Russia went so far as to say that things were better for the Sudanese people under the rule al-Bashir’s dictatorship.

Copied and translated posts

Some of the content posted to the assets de-platformed by Facebook appeared to have been translated from another language. Grammatical errors, such as random changing of pronouns and switches from formal to informal speech were common, combined with the use of phrases that would be confusing to a native Arabic speaker.

In the image below, the blue text indicates a phrase that is not commonly used in Arabic. Text in red boxes contains grammatical errors, while the text in the green box contains a confusing mix of pronouns.

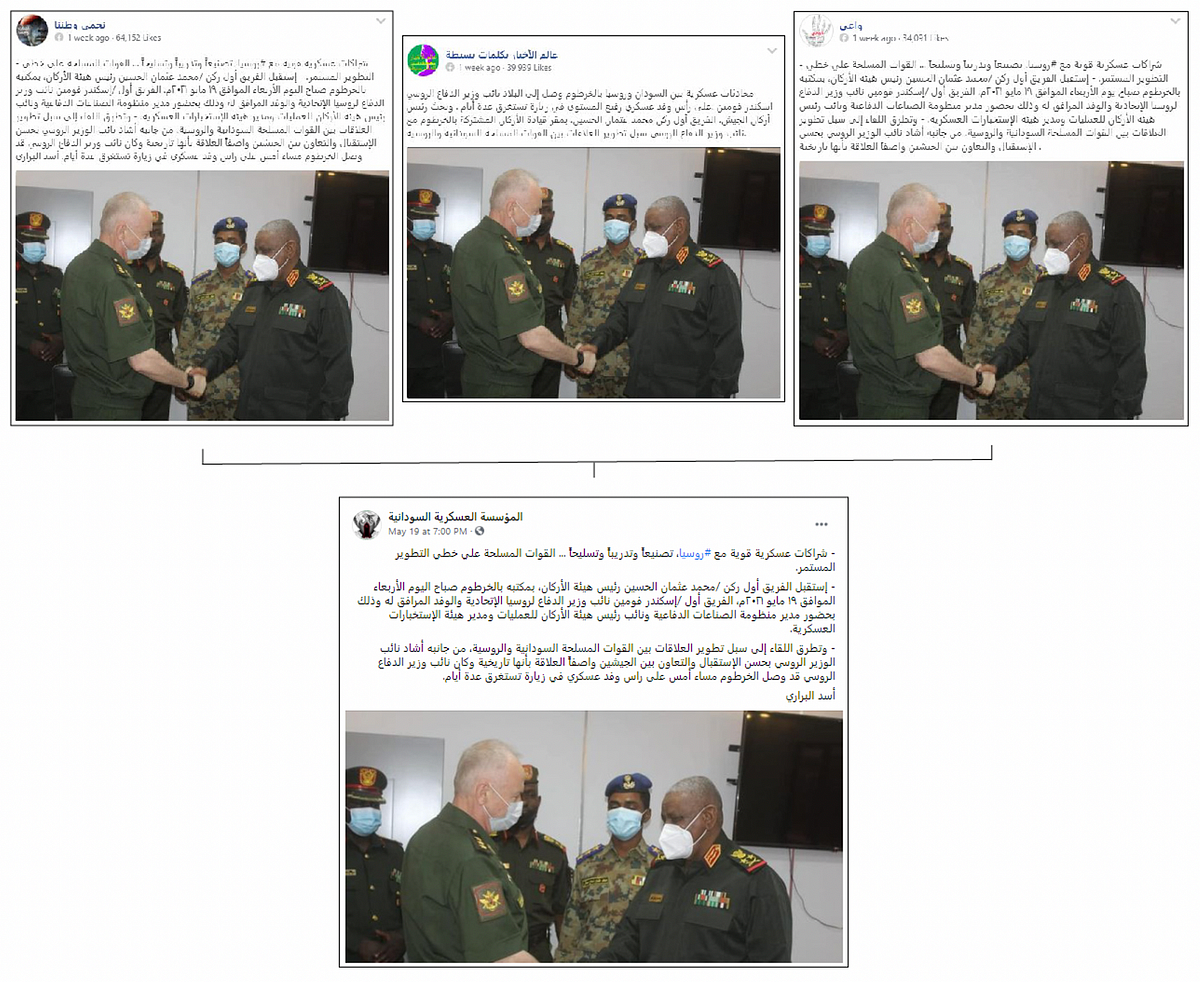

Many posts also appeared to have been copied from other sources, including other Facebook pages. In one instance a meeting between Sudanese and Russian military leaders was copied from a pro-Sudanese military page. In some posts it was edited slightly, but other pages kept the text identical.

Ultimately, the network of assets removed by Facebook appeared to have continued in the footsteps of previous de-platformed networks by promoting Russian interests in Sudan and claiming that Yevgeny Prigozhin was more of a friend to the Sudanese people than their own government could ever be.

The DFRLab team in Cape Town works in partnership with Code for Africa.

Additional research by DFRLab Associate Director Lukas Andriukaitis, and Code for Africa’s iLab Investigative Analyst Lujain Alsedeg.

Cite this case study:

Tessa Knight, “Inauthentic Facebook assets promoted Russian interests in Sudan,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), June 3, 2021, https://dfrlab.org/2021/06/03/inauthentic-facebook-assets-promoted-russian-interests-in-sudan/.