Anonymous Facebook pages heavily promoted Brazil’s pro-Bolsonaro marches

September 7 rallies called for anti-democratic measures; at least two pages appear to be connected to larger organized networks

Banner: “Prison for Supreme Court” reads a placard during a rally in support of President Bolsonaro’s government on Brazil’s Independence Day. Tens of thousands of people have demonstrated in support of Bolsonaro with anti-democratic slogans. (Source: Reuters/DPA/Picture Alliance)

Anonymous Facebook pages — some of them appearing to be part of larger organized networks — gathered significant interactions on Facebook while promoting pro-Jair Bolsonaro marches that took place in early September 2021.

On September 7, 2021, Brazil’s Independence Day, supporters of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro took to the streets to demonstrate in broad favor of the Bolsonaro government. The marches were deemed by critics as a potential threat to democracy, as organizers seemed to share authoritarian ideation in alignment with the president’s own recent behavior, with some fearing the participants might invade Brazil’s Supreme Court much in the same way as the January 6 insurrectionists in the United States attacked the US Capitol. (Those fears were not ultimately realized.) Bolsonaro has already stated that he might not accept the electoral results of next year’s presidential election, and has verbally attacked the Supreme Court using vulgarities and unsubstantiated allegations.

Posts related to the protests gathered thousands of interactions on Facebook. Part of the conversation was led by public figures such as politicians and religious leaders. Among the most prolific actors promoting the marches, however, there were also pages whose owners were unknown. At least one of them seemed to be covertly connected to an extremist Bolsonaro supporter, while another appeared to be part of larger coordinated network.

That politicians and public figures in Brazil have been calling for anti-democratic acts is extremely concerning. But the presence of actors who are hiding themselves behind pages whose owners cannot be identified easily is also troubling, as it makes accountability harder.

Pushing the limits of democracy

Since his rise to political prominence, Bolsonaro has had an openly hostile approach to Brazil’s democracy, including pushing unsupported claims around the country’s electronic voting system during his original 2018 presidential campaign. Indeed, the country’s all-electronic voting system seems to be the president’s most constant democratic bugaboo.

Bolsonaro’s latest threats against Brazil’s democratic system emerged around the end of July 2021, when polls indicated his approval rating were plummeting and that he might lose his 2022 reelection bid. After that, the president reinvigorated his disinformation battle against the country’s electoral system, claiming the electronic voting machines were rigged and even saying there would be “no elections” in 2022 if electronic voting was kept in place.

The judiciary branch, which oversees the country’s electoral process, reacted by announcing they would probe Bolsonaro for spreading disinformation. In a sign that he did not respect the autonomy of other constitutional bodies, Bolsonaro demanded the impeachment of the Supreme Court judge in charge of these investigations. The demand was rejected by the Senate, but it precipitated a constitutional crisis with the incitement of his supporters against the Supreme Court.

Alongside threatening the judiciary, Bolsonaro started to make public statements that sounded like threats. For example, he said he “might have to play outside constitutional lines,” and added, “although he doesn’t want [institutional] disruptions, there are limits to everything in life.”

The marches in support of the president were planned amidst this crisis, with some of the organizers using the internet to promote anti-democratic ideas, calling for the demotion of all Supreme Court justices. Sérgio Reis, a Latin Grammy-nominated singer who supports Bolsonaro, reportedly told a friend on WhatsApp that there would be a truck driver strike alongside the protests and, if the Supreme Court judges did not resign, they would be “taken out by force.” Another organizer used Facebook and Instagram to call on truck drivers to break into the Supreme Court and congressional buildings. The police, following orders from the Supreme Court, raided the organizer’s house and those of other organizers to investigate whether they were fomenting violence.

According to investigations, the protest was financed by farmers, along with the strong support of religious leaders. Another concern was the involvement of military, especially the military police. Ahead of the protests, the governor of the São Paulo state suspended a police colonel after he called online for others to attend the protest; policemen in Brazil are banned from participating in political acts in an official capacity.

After the judiciary branch acted against some of the organizers, however, Bolsonaro, his allies, and protest leaders altered their language, instead claiming that the marches were simply to support the president and promote “freedom.” The change in rhetoric, however, did little to calm fears that the protests would become violent and result in an escalation of authoritarianism in the country.

For many analysts, Bolsonaro is repeating former US President Donald Trump’s playbook by promoting disinformation and causing institutional instability ahead of the 2022 presidential election. The goal would be to undermine the electoral process so that he could gather support to reject electoral results if he fails to win, an increasingly likely scenario based on the most recent polling.

Facebook pages and groups behaving inauthentically

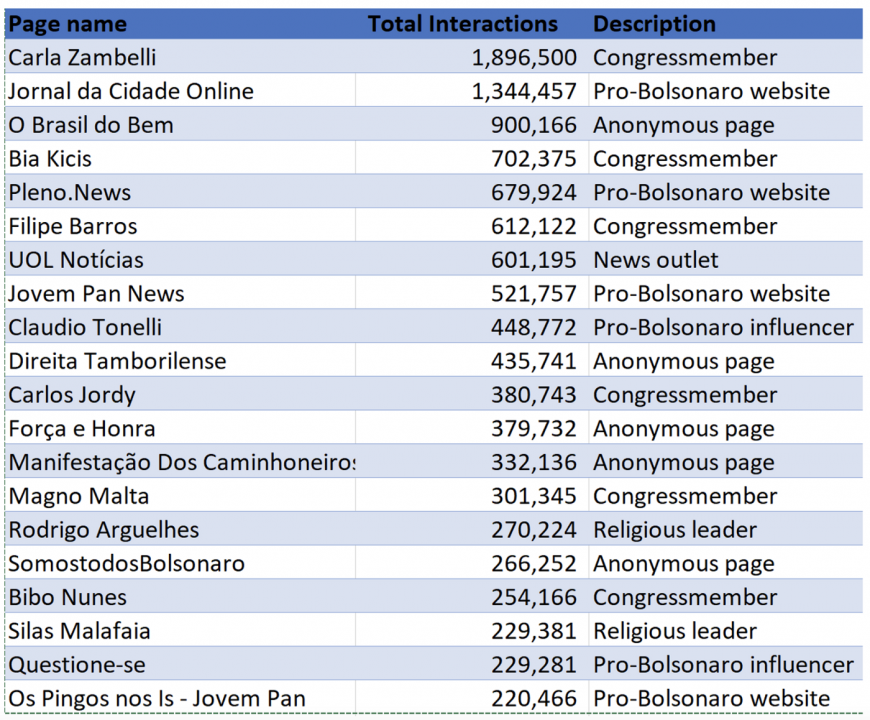

On Facebook, discussion prior to the events was not restricted to high-profile politicians and public figures with large number of followers. Alongside Facebook pages and accounts for congressmembers and religious leaders, anonymous pages and accounts that support the president received some of the highest volume of interaction on the platform.

A search for terms associated with the marches between August 1 and August 31 showed that, among the twenty pages and accounts that attracted the most interactions, five were pages run anonymously.

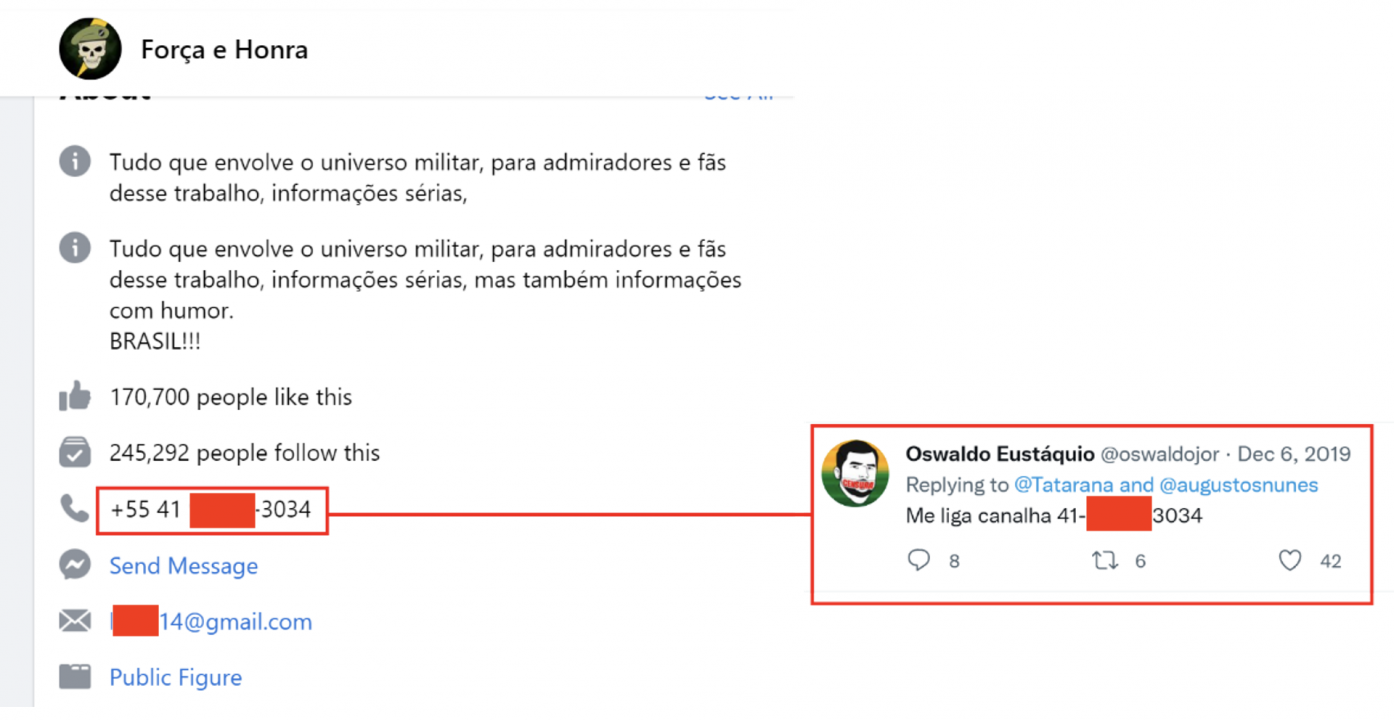

One of these anonymous pages was “Força e Honra” (“Force and Honor”), which describes itself as a page about the “military universe.” The page gathered around 380,000 interactions on Facebook on its different posts calling for the protests. Some of the most prominent posts featured people investigated for organizing the anti-democratic acts that are now being investigated by law enforcement.

Although the owner of the page was not identified in the page’s About section, it listed a phone number and email address. According to a search on Twitter, the phone number belongs to Oswaldo Eustáquio, a journalist who was arrested in 2020 for encouraging extremist and anti-democratic acts. Estáquio’s Facebook page was blocked following a ruling of the Brazilian Supreme Court and, according to himself, was only established in late August 2021.

The email that appeared on the page’s About session, however, belonged to a Eustáquio’s friend Hugo Alves, according to a LinkedIn search. Some videos posted to the page also identify Alves as the owner of the page.

Both Eustáquio and Alves have official Facebook pages.

Although these pages cross-promote content — for instance, they broadcast the same live video featuring Eustáquio on September 2 — neither Estáquio’s nor Alves’s official page acknowledges the existence of “Força e Honra” as a related page. This suggests that they might be using “Força e Honra” to reach a different audience, potentially in violation of Facebook authenticity policies that do not allow a person to “conceal a Page’s purpose by misleading users about the ownership or control of that Page.”

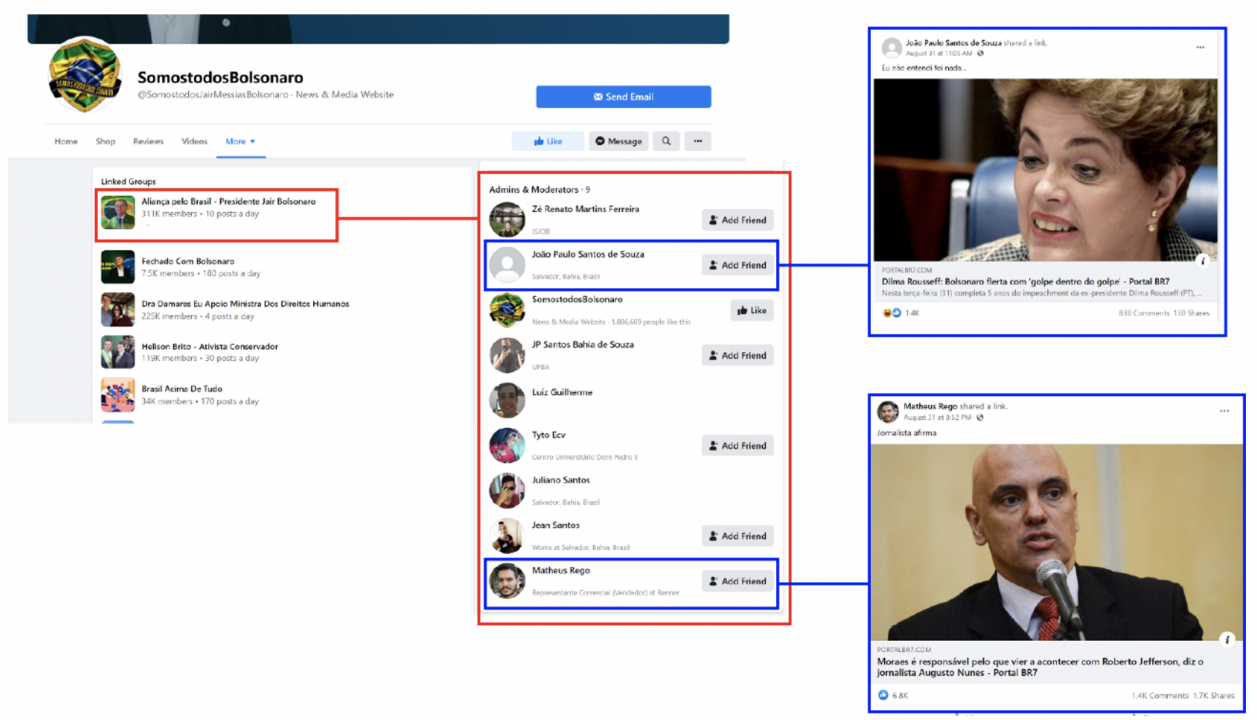

Another anonymous page that received considerable engagement was “Somos Todos Bolsonaro” (“We are all Bolsonaro”). The page garnered 266,000 interactions on posts of website articles about the protests and posts calling for the marches.

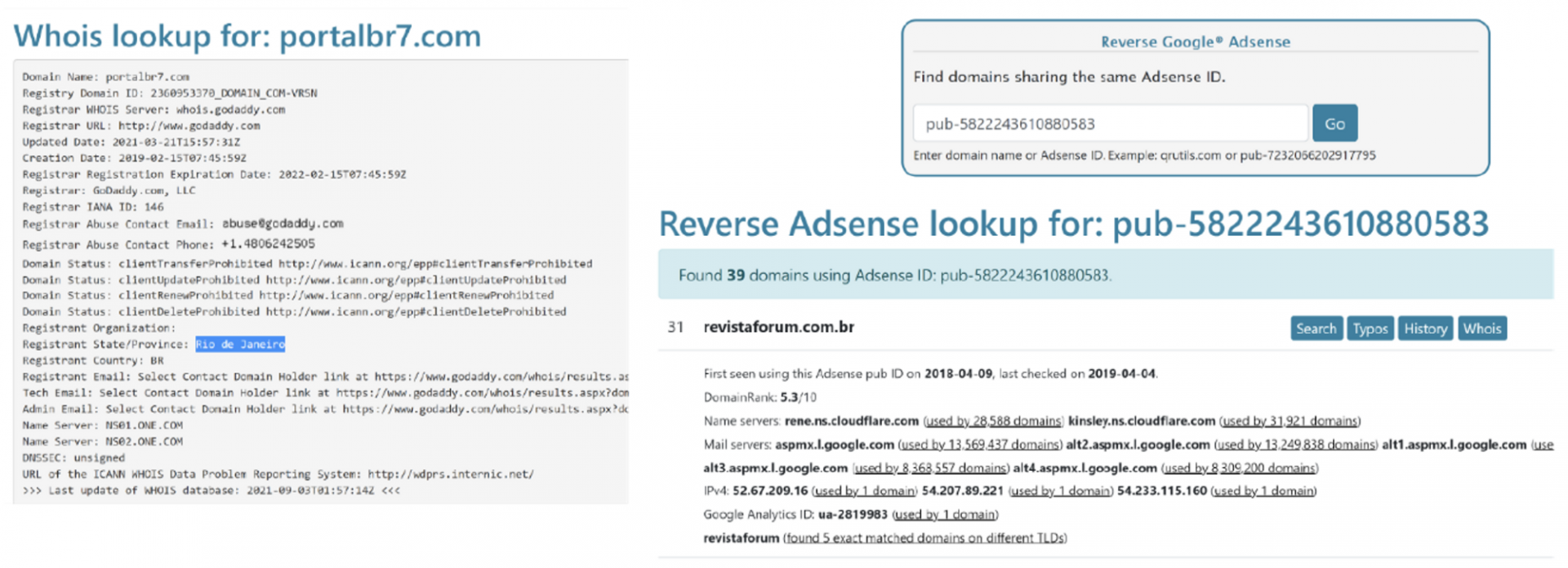

“Somos Todos Bolsonaro” presents itself as a “news and media website” and links to external website “portalbr7.com” on its About page. The website, however, has its own official Facebook page, and does not link to the “Somos Todos Bolsonaro” page on its website. It is possible that “Somos Todos Bolsonaro” has no connection to the website and is unlawfully claiming a connection to it. It is also possible, though, that the page is related to the website but, for some reason, is not their official Facebook page.

PortalBR7 does not state who its owners are on its website. It was registered anonymously in the city of Rio de Janeiro via GoDaddy, according to a WHOIS search of the domain name. It shares a Google Adsense ID (an ad tracker number) with another thirty-nine domains, including well-known left-leaning websites in Brazil. Rather than suggesting that all these websites are connected to the same owners, however, this might indicate that all their advertisements are managed by the same firm.

Besides the possible connection to this website, “Somos Todos Bolsonaro” is connected to different Facebook groups. The page lists fourteen groups on its “related group” session, three of which are owned by the page. Admins and moderators of the largest of these groups, named “Aliança pelo Brasil” (“Alliance for Brazil”) after the party Bolsonaro attempted to create, frequently shared articles from PortalBR7 to the groups, further raising the possibility that the page and groups might have been part of a coordinated effort to amplify the website.

Image map showing how Somos Todos Bolsonaro listed “Aliança pelo Brasil” as a “linked group” on Facebook; the moderators of the Aliança pelo Brasil group; and how two of those same moderators share links to portalbr7.com stories to the group. (Source: Facebook)

Among the other anonymous pages that garnered interactions were a page connected to a truck driver and two that do not seem connected to larger networks. Per its Instagram account, for example, “Brasil do Bem” appeared to belong to a person called “Daniel Correa,” but the DFRLab was unable to find open-source evidence about this person. Elsewhere, the phone number provided on the page “Direita Tamborilense” indicates that it belongs to a couple that lives in the Northeast of Brazil, while the final page, “Manifestação Dos Caminhoneiros Do ES,” apparently belonged to Bira Nobre, a truck driver who ran for state legislator in 2018.

As fears of authoritarianism rise in Brazil, identifying how potential inciteful information flows online becomes essential. While law enforcement, researchers, and journalists had already identified the main organizers and public figures who promoted the September 7 marches, anonymous pages were also responsible for a significant part of the conversation.

Signs that some of these pages are connected to larger networks, including to actors who have been probed for promoting anti-democratic ideas in the past, raise concerns about the possibility that these pages are hiding behind a façade of anonymity to promote anti-democratic ideas.

Cite this case study

Luiza Bandeira, “Anonymous Facebook pages heavily promoted Brazil’s pro-Bolsonaro marches,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), September 28, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/anonymous-facebook-pages-heavily-promoted-brazils-pro-bolsonaro-marches-335f4757a44b.