Givi Gigitashvili, “Suspicious Twitter accounts amplified hashtags ahead of Polish nationalist march,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), November 15, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/suspicious-twitter-accounts-amplified-hashtags-ahead-of-polish-nationalist-march-4fcf1a69de93.

Suspicious Twitter accounts amplified hashtags ahead of Polish nationalist march

Accounts promoting a nationalist march in Poland exhibited multiple indicators raising questions of their authenticity.

Suspicious Twitter accounts amplified hashtags ahead of Polish nationalist march

Share this story

BANNER: Far-right groups march in Warsaw on Polish Independence Day, November 11, 2021. (Source: Jakub Podkowiak/PRESSCOV/Sipa USA via Reuters Connect)

At least 100 Twitter accounts amplifying hashtags connected to a controversial far-right independence march in Poland exhibited multiple indicators of bot-like behavior. Whether run by actual people or automated, such accounts can be used for deceptive purposes, such as inauthentically boosting politically motivated hashtags into Twitter’s “trending” list, creating a false sense of their relative popularity.

Nationalist groups hosted the march on Poland’s Independence Day on November 11, 2021. The organizer, the Independence March Association, has hosted the annual event since 2011. One of most prominent far-right groups within the association is the National Radical Camp (ONR), which according to Poland’s Supreme Court legally qualifies as a fascist group.

The march has a recent history of violence. In 2017, a group of women activists protesting the event were brutally attacked by male participants; the women later faced charges of disrupting a legal assembly but were acquitted in 2019. During the 2020 march, which took place without a permit and in defiance of pandemic restrictions, nationalists clashed with police. After several officers were injured, police used tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the crowd. This history of violence had raised concerns about public safety during this year’s event.

The 2021 march

Prior to this year’s march, the Independence March Association petitioned authorities to re-designate the march as a “cyclical” event — a status required by Polish law to prioritize annual events over others attempting to register for the same date and location. The march previously held this designation, but it was revoked in 2020 after Polish authorities refused permits for the event. The request to re-designate the march as cyclical was granted by Konstanty Radziwiłł, governor of Masovia province and a member of the ruling right-wing Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS in Polish).

In a bid to revoke the permit, Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski, a member of centrist opposition party Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, or PO), appealed Governor Radziwiłł’s decision in a Warsaw court. Mayor Trzaskowski argued that the 2020 march did not officially take place, since it occurred without a permit and in defiance of pandemic restrictions; this, he claimed, meant it could no longer be deemed a “cyclical” event. On October 27, 2021, a court accepted the mayor’s appeal and overturned the governor’s decision to grant the march cyclical status.

After his successful appeal, Mayor Trzaskowski wrote on Twitter that the march would now constitute an illegal gathering. On November 10, one day prior to the march, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs Błażej Poboży appealed to the authorities of Warsaw to remove “stones, gravel, and cobblestones” from the streets to prevent provocateurs from disturbing the peaceful march. (It is unclear if any such action took place.)

Despite the October 27 ruling, the march went ahead in Warsaw as originally planned on November 11. Organizers said that up to 100,000 people participated. Unlike recent years, there were no major incidents of violence during the march, and Mayor Trzaskowski described the gathering as “calm.” However, participants of the march publicly burned the German flag, an image of Polish opposition leader Donald Tusk, and the LGBT flag, all of which symbolize for the participants a liberal international order in opposition to their nationalist sentiments. Police also arrested several participants.

A few days before the court’s decision on October 27, the DFRLab observed suspicious Twitter accounts amplifying hashtags connected to the march. Though these hashtags were initially launched by march organizers, the suspicious accounts started to promote them, possibly in an effort to reinforce the false impression of broader support on Twitter.

The DFRLab analyzed the following hashtags:

#MarszNiepodległości (“Independence March”) — a general hashtag connected to the march that was actively promoted by the official Twitter account of the Independence March and other far-right organizers of the event. By promoting this hashtag after October 27, 2021, organizers conveyed a message that the march would still take place despite court’s decision.

#MarszNiepodległości2021 (“Independence March 2021”) — promoted the 2021 march.

#NiepodległośćNieNaSprzedaż (“Independence is not for sale”) — the slogan for this year’s march; Polish nationalists claim that Poland sold its independence to the European Union (EU) in exchange for money and strongly oppose “relinquishing independence” for EU financial assistance.

#11listopada (“November 11”) — promoted annually by nationalists ahead of the march and Polish Independence Day.

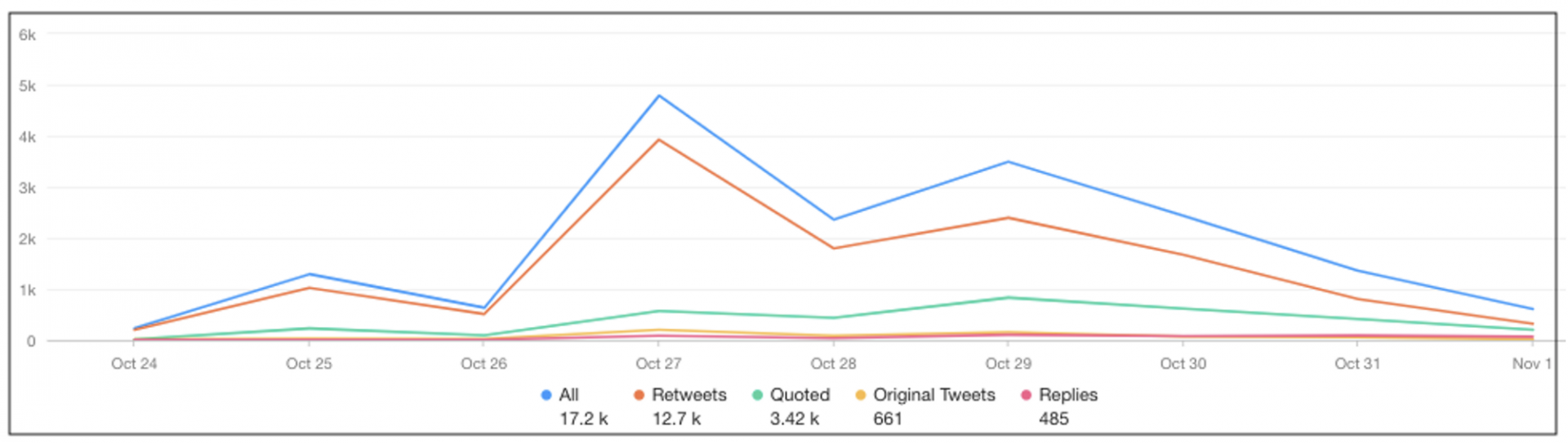

A review of Twitter data using the monitoring tool Meltwater Explore showed that 17,280 tweets mentioned these hashtags between October 24 and November 1, with mentions reaching the highest volume on October 27, when the court’s decision became public. A closer look at Twitter accounts mentioning the hashtag showed that many of them exhibited signs of unusual behavior.

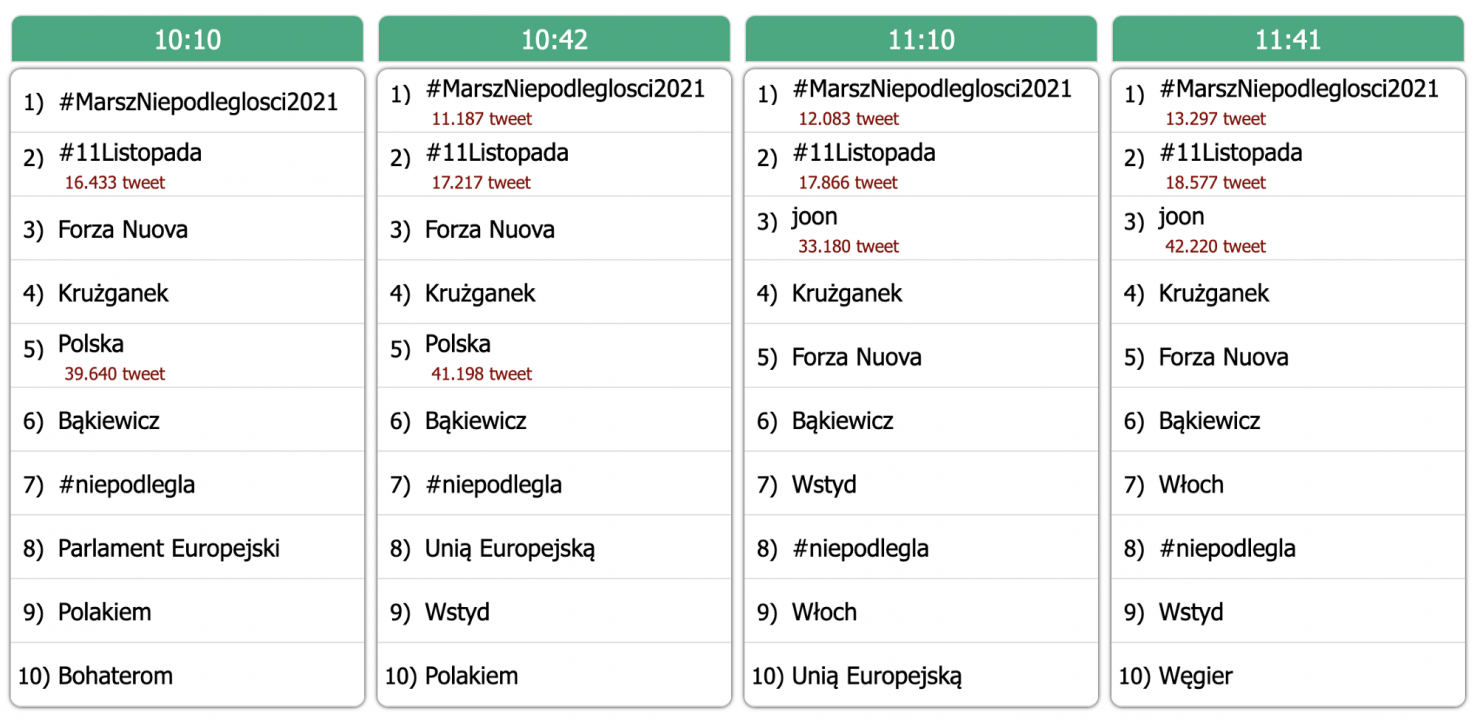

The DFRLab analyzed mentions for each of these hashtags between October 24 and November 1, 2021, and found that #MarszNiepodległości was the most popular hashtag of the group during the observation period. According to trending data collected by the Twitter Trending Archive tracker, the hashtag trended throughout the day of the court ruling and the day afterwards. On the afternoon of the march, it reached the top of Poland’s trending list, ultimately landing as the top five most mentioned trending topics that day.

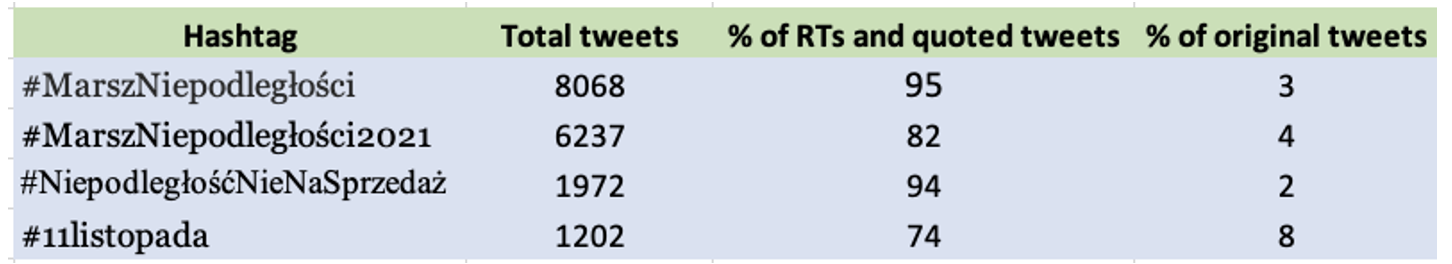

For all four hashtags, a majority of mentions came from retweets and quote tweets rather than original tweets.

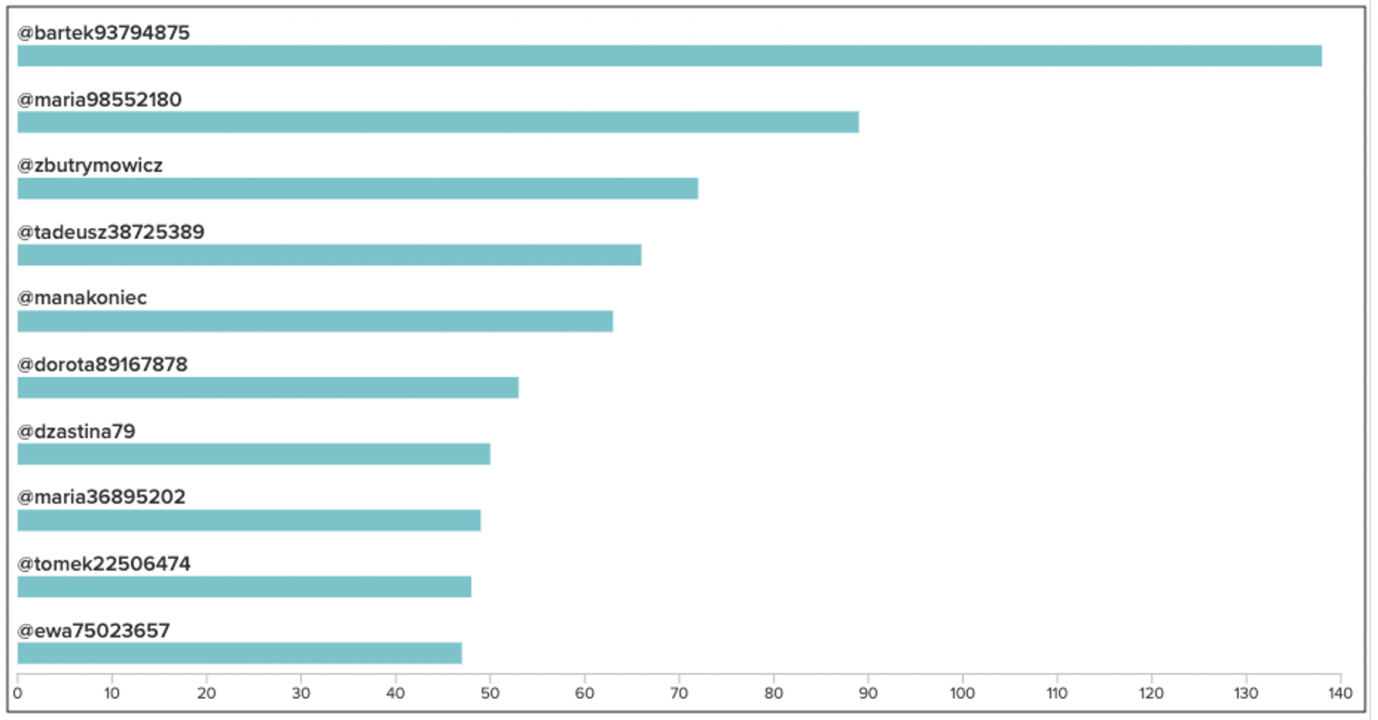

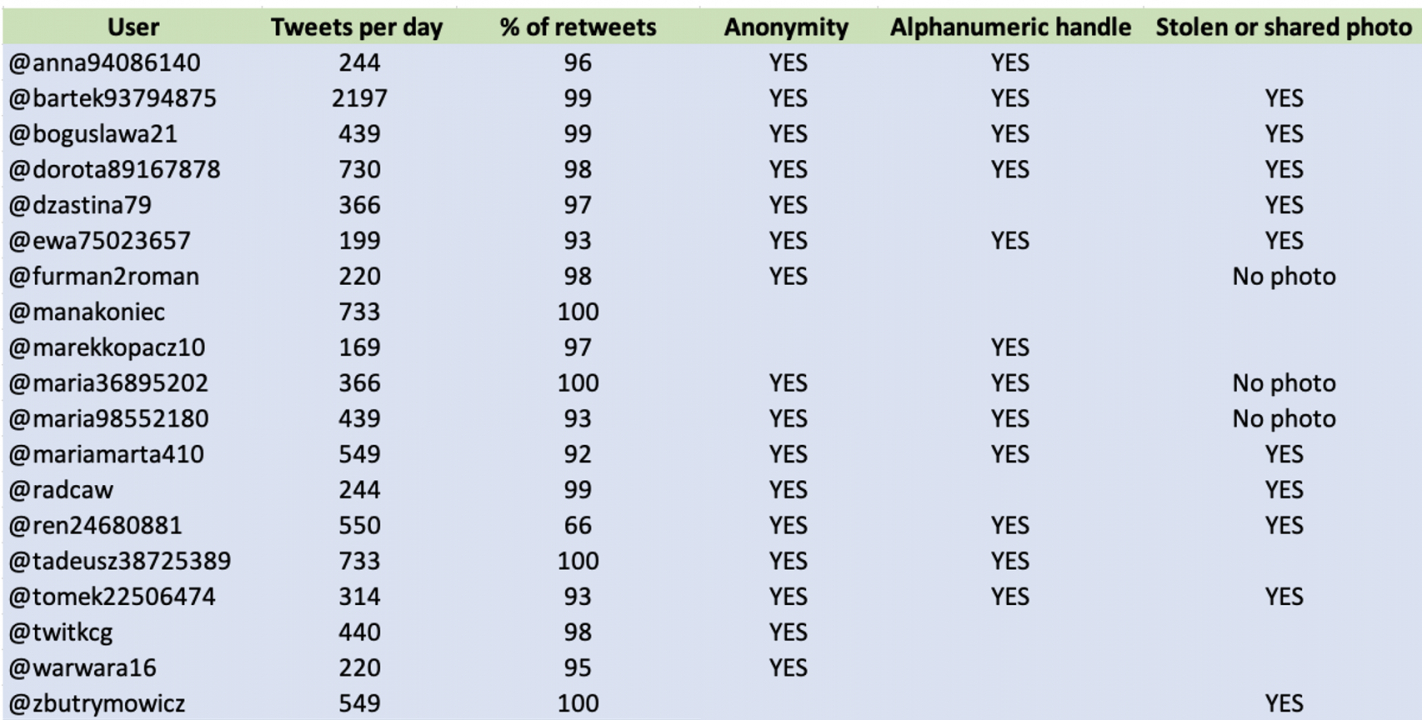

An analysis of the 10 most active Twitter accounts showed that they posted these hashtags 675 times in total during the observation window. An analysis of these accounts using the DFRLab’s bot identification framework and open-source tool Truthnest revealed that they all exhibited indicators of bot-like behavior.

After an initial analysis of the top 10 accounts revealed suspicious behavior, the DFRLab expanded its analysis using its bot identification framework to review the top 100 most active accounts and found that all of these accounts posted at least one of the selected hashtag no less than than 15 times during the observation window. Of the 100 accounts analyzed, 76 of them posted more than 144 tweets per day, while the remaining 24 posted between 72 and 99 tweets per day, based on a sample of their most recent 2,200 tweets. The DFRLab generally regards posting more than 72 times a day as suspicious and more than 144 times as highly suspicious, though it is not unusual for politically active Twitter accounts to post at high rates, especially around notable events. In this case, though, some of the accounts posted more than 500 times a day, with one account, @bartek93794875, averaging an extraordinary 2,197 per day, which is particularly unusual for typical Twitter users.

To further investigate the behavior of these accounts, the DFRLab studied the amplification efforts of the accounts, noting the hashtags had a high ratio of retweets or quote tweets using the exact same text to original tweets. A Truthnest query of the 100 most active accounts showed that for 92 accounts, more than 90 percent of their content was retweets or quote tweets, and for the remaining eight accounts the figure was more than 85 percent.

Another common indicator of bot-like behavior is using alphanumeric handles, indicating these automated accounts are possibly generated by Twitter’s algorithm. Of the 100 accounts analyzed, 41 had alphanumeric handles, including @bartek93794875 (2,197 tweets per day), @tadeusz38725389 (733 per day), @maria98552180 (439 per day), and @maria36895202 (366 per day).

The fourth indicator of potential bot-like behavior is anonymity, in which accounts do not provide personal details in their bio or use generic profile photos. Notably, at least 85 of the 100 accounts analyzed showed signs of anonymity.

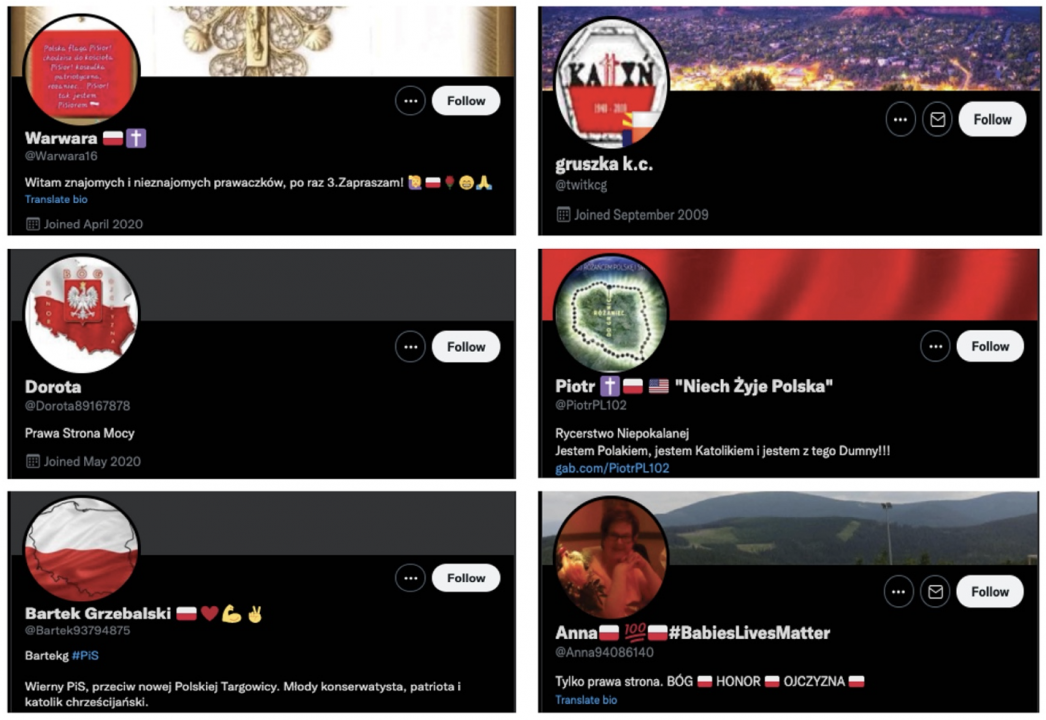

In terms of content, the DFRLab examined these profiles and found some of them to contain potential signs of nationalism including the use of the Polish flag in their profile photos and names. Their profile bios also said that they support right-wing ideology or the ruling PiS party.

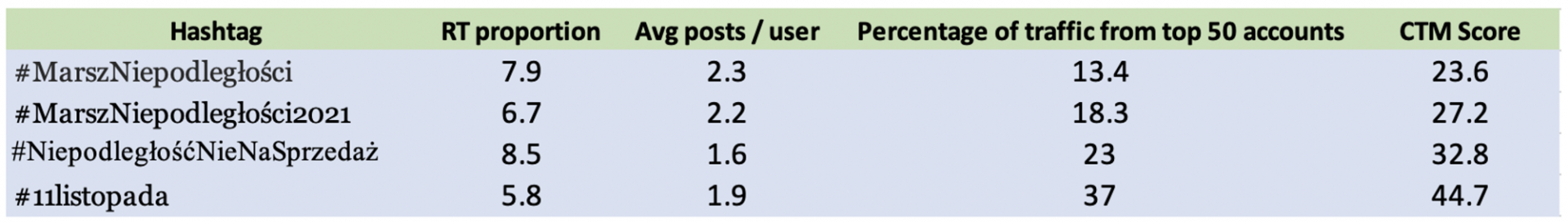

The DFRLab also measured traffic manipulation on these hashtags using the Coefficient of Traffic Manipulation (CTM). CTM measures the likelihood of manipulation of traffic flow, which is defined as “an attempt by a small group of users to generate a large flow of Twitter traffic, disproportionate to the number of users involved.” A DFRLab report on CTM published by the Oxford Internet Institute found that organic, non-manipulated control samples scored a CTM of 12 or lower. All four of the examined hashtags scored higher than 23.

The CTM is expressed by the following equation, in which R is the percentage of retweets, F is the percentage of tweets from the 50 most active accounts, and U is the average number of posts per user: CTM = (R/10) + F + U. The DFRLab’s analysis showed that the #MarszNiepodległości hashtag registered the lowest CTM score, while #11listopada registered the highest score.

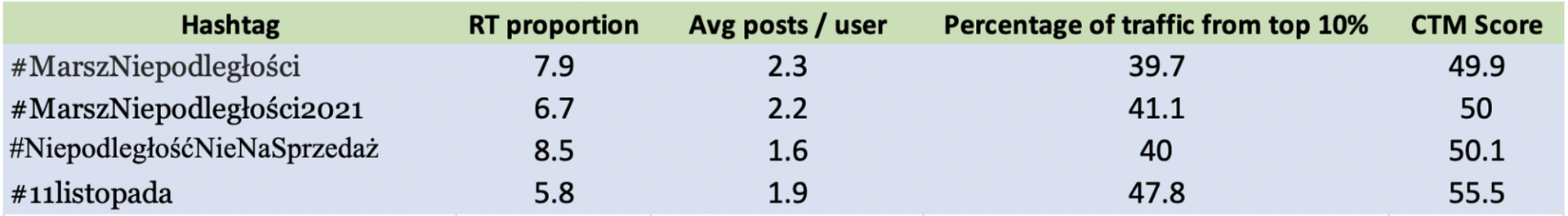

However, the proportion of traffic generated by the 50 most active accounts can be an insufficient indicator of hashtag manipulation when taking into consideration that traffic flows per selected hashtags significantly differ in size. To address this caveat, the DFRLab calculated CTM scores for each selected hashtag based on the top 10 percent of most active accounts.

The DFRLab found that the most active 10 percent of accounts registered more than around 40 percent of the mentions on average. This adds more evidence to the finding that a small group of accounts likely tried to manipulate traffic on selected hashtags.