China’s COVID-19 messaging makes its way to South Africa

China leverages its investment in the South African media space to push Beijing-approved narratives and conspiracies.

China’s COVID-19 messaging makes its way to South Africa

Share this story

BANNER: (Source: Chinese Embassy in South Africa/archive)

From June through September 2021, China amplified Beijing-approved narratives and a conspiracy theory on the origin of COVID-19 in the local South African media space by leveraging its content exchange and syndication agreements with South African partner news organizations.

China’s actions in South Africa are part of a broader media strategy in Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2008, as part of China’s “going out” strategy, then-Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao urged Chinese media companies to go international and “present a true picture of China to the World.” This call was partly in response to what Beijing saw as unfair coverage of China during the 2008 Summer Olympic Games, in which Western media criticized China over its crackdown in Tibet while downplaying China’s achievements in hosting a successful Olympics. Beijing sees control over information space as critical for smoothing the way for Beijing to spread a positive “China story” (讲好中国故事) that pushes an image of China as a responsible power, and to create buy-in for Chinese concepts like “non-interference” over Western-focused “universal values” as the legitimate framework for international relations. It sees Sub-Saharan Africa in particular as fertile ground for these ambitions, due to what it sees as a shared history of foreign interference and a common experience as developing countries.

China’s media relationship with South Africa makes it a compelling case study for examining Chinese influence on the continent. For one, state-owned media outlet Xinhua’s content is available at no cost through a syndication agreement with South Africa’s African News Agency (ANA). And in a Global Media and China analysis of Chinese media influence in 30 African countries, Assistant Professor Dani Madrid-Morales of the University of Houston found that South African online portal iol.co.za was the top driver of news coverage of China in English-speaking Africa among all the sites surveyed. In 2018, China’s media influence in South Africa made headlines when South African journalist Azad Essa lost his column in Independent Media, which operates the online news media site Independent Online (IOL), following his report criticizing the persecution of Uyghurs in China. IOL, the second-largest media group in the country, is 20 percent owned by Chinese state entities.

The case study below looks in deeper detail at Chinese state media involvement in South Africa’s local media space. It shows the presence of a self-feeding mechanism: Chinese state sources push a particular narrative; local reports from China-funded local papers amplify it; then Chinese state media picks up these reports, editorializes them, and feeds them back into the South African media ecosystem through its distribution agreements. Chinese-linked actors and state media strongly pushed a narrative criticizing US “politicization” of the COVID-19 origin-tracing process following the release of a World Health Organization (WHO) report on where and how the disease arose. Claims of US politicization were reported in China-funded South African media; Chinese state media picked up this coverage, editorialized it, then distributed it back into South Africa’s local media space as free content.

In another example, Chinese state media engaged in the same process to elevate a conspiracy theory claiming COVID-19 originated in the United States rather than China. This conspiracy was first pushed by Chinese state media, picked up by a South African outlet, then editorialized and pushed by Chinese state media both in South Africa and internationally.

China’s investment in African media

China has greatly expanded the footprint of its state media in Sub-Saharan Africa in the past several years. China’s official state media agency, Xinhua, moved its Sub-Saharan Africa editorial offices from the Chinese mainland to Nairobi in 2006, and, in 2009, Beijing invested $6.6 billion to expand Xinhua’s footprint on the continent. By 2012, the state-run newspaper China Daily had launched its African edition, and China’s state-run television channel opened its first station outside of China in Nairobi, Kenya. In recent years, China has also established several initiatives under the auspices of the Beijing-led Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), including the subgroup the “Forum on China-Africa Media Cooperation (中非媒体合作论坛), and other programs under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), including the “Belt and Road Media Community Summit” (丝绸之路电视共同体高峰论坛), the “Belt and Road News Alliance” (“一带一路”新闻合作联盟). It has also built partnerships between foreign media outlets and China Central Television (CCTV), the official state broadcaster for China, in order to promote BRI. As of 2020, 30 in the Belt and Road Media Community Summit Forum participated in the Belt and Road Media Community Summit Forum.

The actual impact of Beijing’s efforts in the South African public media sphere is not fully understood, though academic researchers have determined that, what is evident so far, is mixed at best. For instance, Herman Wasserman, Professor of Media Studies at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, found in a recent study that South African journalists have not been overly influenced by the increasing presence of Chinese sources in the local media environment. Wasserman’s study revealed that South African journalists did not routinely access Chinese media to report on China-related events and relied on Western sources instead. Likewise, Dani Madrid-Morales, Assistant Professor of Journalism at the University of Houston, analyzed a database of 500,000 news articles and found that both French and English-language African news outlets — not just in South Africa — were less likely to use prepackaged content distributed by Chinese media (e.g., Xinhua, China Daily) over content from other major global media players (e.g., Reuters, AFP).

While studies indicate that China’s impact on press freedom in South Africa is minimal at best, this may not be the case in the rest of the continent. According to the 2021 World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), South Africa ranked 32 out of 180 countries evaluated by the organization, above the United States and the United Kingdom. Reporters Without Borders characterizes the country’s press environment as “guaranteed but fragile,” as the country’s 1996 constitution protects press freedom and an investigative journalism culture is well-established in the country. However, the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa is a different story. According to RSF, “with reporters attacked and arrested, their incomes failing, and media undermined by disinformation and draconian laws, the coronavirus pandemic has compounded the huge difficulties for journalism in Sub-Saharan Africa, where 23 of the 48 countries (two more than in 2020) are now marked as red or black on the World Press Freedom map, meaning the situation is classified as bad or very bad.” It remains “the world’s most dangerous continent for journalists in 2021.”

China’s growing influence in the media spaces of countries where press freedom is already fragile is troubling. Recent public-opinion polling supports the view that Chinese engagement on the continent is generally viewed in a positive light. Nonpartisan research institution Afrobarometer conducted surveys measuring public attitude toward China in 16 African countries between 2019 and 2020 and found that 59 percent of people surveyed viewed China’s economic and political influence in the continent as “somewhat or very positive,” compared to 58 percent who stated that US political and economic influence in their respective countries was “somewhat or mostly positive.”15 However, these results are down slightly from the last time the survey was conducted, over 2014–2015, in which 65 percent of those surveyed reported China’s influence as “somewhat” or “very positive.”

Similarly, Wasserman and Madrid-Morales have studied the reception and consumption of Chinese media in Sub-Saharan Africa since 2014. While their studies suggest that direct exposure to Chinese media, such as China Radio International (CRI) or CGTN Africa, is modest at best, they state that China’s strategy of distributing content to local African news media may have a greater impact. In 2019, Madrid-Morales analyzed28,000 news articles from over 100 news outlets in 28 countries, including 10 in Sub-Saharan Africa. Morales found that coverage of topics like BRI in Africa was “overwhelmingly positive,” compared to its coverage in countries like the United States and India.

Madrid-Morales stated that the skewed coverage could in large part be due to the fact that content from Chinese state media is often provided to local news agencies at low to no cost. This uptick in Chinese-sourced coverage is partly explained by the syndication agreements and content exchanges that Chinese state media have signed with a growing number of African partner organizations. Through these agreements, state media content is often available at no or low cost for newsrooms to distribute, including for example by Ghana’s News Agency (GNA) and South Africa’s African News Agency (ANA), as mentioned above.

As with sub-Saharan Africa more broadly, China’s activity in the South African media space has garnered increasing attention. Specifically, policymakers and civil society actors have pointed out China’s increased investment in South African media companies and questioned whether this has influenced press freedom in the country. As mentioned above, one well-known example is Independent Online (IOL), a news and information website in South Africa, 20 percent of which is controlled by Chinese state entities, including the China-Africa Private Development Fund (CADFUND) and China International Television Corporation (CITVC).

South African journalists are skeptical of companies, like IOL, that are heavily influenced by Chinese funding and express suspicion over their ties to South African government entities. For example, Chinese state backing facilitated the purchase of IOL by the Sekunjalo Consortium, whose leader has close ties to the ruling party in South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC). Journalists, civil society activists, scholars, and some opposition party members in South Africa are also skeptical of the ANC’s relationship with Beijing. For example, in 2009, members of South African opposition parties pointed to the sizeable campaign contributions the ANC received from Chinese donors as reasons for the party’s relative silence on China’s human rights record. The ANC has also blocked the Dalai Lama’s entry into South Africa on at least two occasions, following Beijing’s wishes, moves that opposition party members also criticized.

Some critics have also argued that, under President Jacob Zuma’s tenure from 2009–2018, the ANC sought to model itself after the CCP to prolong its rule. These criticisms appeared again in 2019 after then-Secretary General of the ANC Ace Magashule announced that the party’s members would engage in a CCP-led training program in advance of the 2019 elections. In February 2021, the South African Communist Party, an alliance partner of the ANC, and the CCP had held a joint celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of both parties, hosted by ChinAfrica magazine, a China state-owned publication targeting an African audience. In September, News24, a news outlet owned by South African-based media company Media24, reported that South African security services believed there was a “high likelihood” that Member of Parliament and ANC member Xiaomei Havard was working directly with the CCP’s United Front Work Department to pass classified information from South Africa’s government to the CCP.

China’s COVID-19 politicization narrative and the South African media space

In the first half of 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic shuttered economies across the globe, the United States and other Western countries frequently criticized China over its lack of transparency regarding the origin of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. This dynamic event led then-US President Donald Trump to announce in July 2020 that the United States would pull out of the WHO in response to it being too “subservient” to Beijing; President Joe Biden subsequently reversed this decision in one of his earliest executive orders.

In response to Western criticisms, China began to put out its own counter-messages accusing the United States of “politicizing” the coronavirus for its own ends. In the first half of 2020, Chinese diplomats and state media pushed these narratives among African counterparts. For example, on June 17, 2020, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered the keynote speech via video at the “Extraordinary China-Africa Summit on Solidarity against COVID-19,” attended by China, South Africa as the representative of the African Union, and Senegal representing FOCAC. Several African leaders also attended.

During his speech, Xi committed China to supporting the pandemic response in Africa. Xi then spent several minutes warning against the “politicization and stigmatization of COVID-19.” In a joint statement following the event, attending African countries “condemned the politicization of the virus and the ‘disinformation’ surrounding it,” “commended the Chinese government for its early efforts to contain the spread of the virus transparently,” and stressed the importance of “opposing the politicization of the epidemic” as a joint priority. ANC Chairman and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa also delivered remarks at the Summit, congratulating the CCP on its 100th anniversary and praising Xi’s leadership.

On March 30, 2021, the WHO released its long-awaited report on possible origin scenarios for COVID-19. The report came after a month-long investigation from a WHO team sent to Wuhan, China, in January with the explicit task of investigating how and where the virus entered the human population. Following the release of the report, on March 30, the United States and 13 other countries issued a joint statement outlining concerns that the report “was significantly delayed and lacked access to complete, original data and samples.” In a press conference the same day, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki criticized China’s lack of transparency when asked about the country’s participation in the WHO report, stating: “Well, they have not been transparent. They have not provided underlying data. That certainly doesn’t qualify as cooperation.”

In response to the joint statement, on March 31, China criticized “political manipulation” and “politicizing” the virus, with Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying stating: “We have repeatedly emphasized that origin tracing is a scientific issue, and it should be carried out cooperatively by global scientists and cannot be politicized, which is also the consensus of most countries… The politicization of origin tracing is extremely immoral and unpopular, which only hinders global cooperation and [the] global fight against the virus.” Partly in response to criticisms from the United States and other countries, the WHO proposed a second phase of COVID-19 investigations in China on July 16, which the latter rejected on July 22, instead calling on the WHO to “truly treat the origin tracing of the COVID-19 virus as a scientific matter, and get rid of political interference.”

Beginning in July 2021, China prioritized the COVID-19 politicization issue in its diplomatic engagements. In nearly every public meeting with a foreign counterpart beginning on July 16, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi emphasized the “politicization of COVID-19” as China’s core foreign policy concern. For example, in a readout of his meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on July 16, as posted on the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, Wang stated: “We must continue to work together to oppose the stigmatization and politicization of the COVID-19 pandemic and the virus origin tracing.” On July 24, Wang met with Portuguese Foreign Minister Augusto Santos Silva; the headline for the meeting in Chinese state media was “Wang and Portuguese counterpart slam politicization of COVID-19.” Wang made similar remarks during a meeting with Finnish Foreign Minister Pekka Haavisto on July 25, for which a readout of his remarks read: “the US has been trying to politicize the outbreak, stigmatize the virus, instrumentalize the virus origins-tracing work and hyped the lab leak conspiracy theory.” At a Ministry of Foreign Affairs Press Conference on July 30, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian emphasized that “stopping the politicization of COVID-origin tracing” was essential to pandemic recovery.

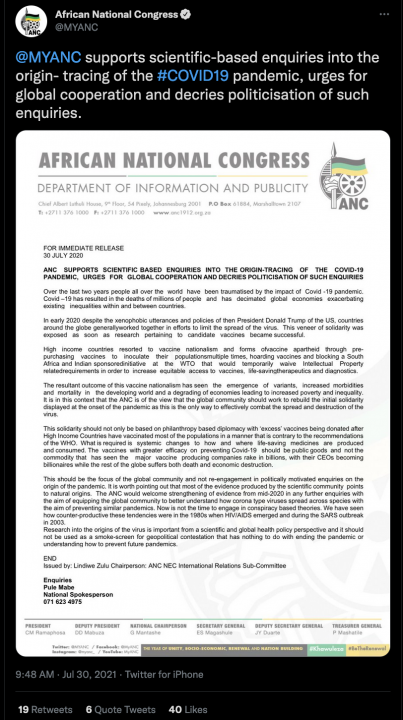

The same day of Zhao’s press conference, the ANC released its own statement on Twitter in which it “decrie[d] politicization” of COVID-19 origin tracing.

While the ANC statement did not mention China or the United States specifically, it is similar to Chinese state narratives emphasizing “science-based inquiries” and “politicization of COVID origin-tracing.” The statement was picked up by Chinese state media and circulated in both its English and Chinese-language editions, to create the impression that the ANC directly supported China’s narrative. The day following the ANC statement, Xinhua published an article titled “Stop politicizing COVID-19 origin tracing — S. Africa’s governing party.” Xinhua released a series of articles over the following days that cited the ANC statement but that were also heavily editorialized to fit Chinese priorities. For example, in a Xinhua article published August 2, the article cited the ANC statement before accusing the United States of pressuring WHO to skew the results of the report: “Experts have also voiced concerns about the WHO’s independence in the matters, saying that some WHO experts and researchers were under enormous pressure or even intimidated by the United States after they voiced support for the conclusions of the China-WHO joint study on COVID-19 origins in the Chinese city of Wuhan.”

The Xinhua articles featuring the ANC statements were then distributed to local South African news organizations under the content distribution agreement Chinese state media has with IOL, which published the articles on its website with the editorialized content from Xinhua included. In this instance, local news about a statement from the ANC was picked up by Chinese state media, editorialized to fit its narrative priorities, then redistributed back into the South African media ecosystem on local media platforms.

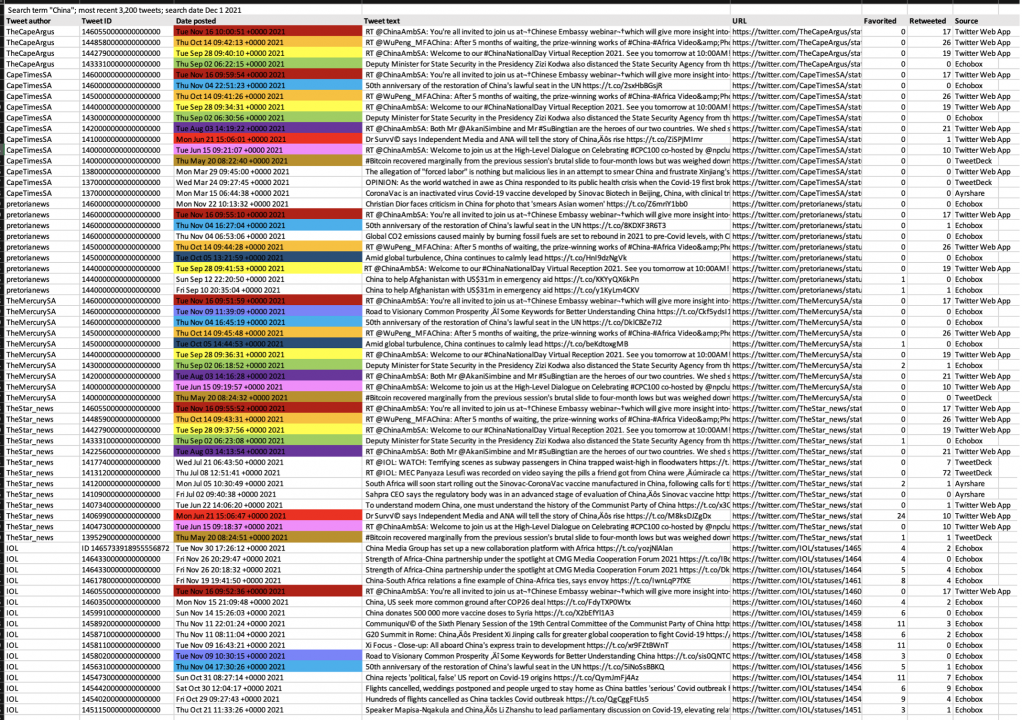

IOL oversees several news organizations in South Africa with sizeable Twitter followings, including @TheCapeArgus (with 46,900 followers), @CapeTimesSA (38,500 followers), @pretorianews (41,600 followers), @TheMercurySA (222.9k followers), @TheStar_news (with 220.8k followers), and @IOL itself (560,500 followers). The news items that IOL receives from Xinhua are distributed to these other media platforms, which in turn release the content on their websites or social media platforms. A search of the most recent 3,500 tweets for each of the above Twitter handles found that news with the term “China” often consists of retweets from Chinese diplomatic accounts and Xinhua-provided content; preliminary sentiment analysis finds that the vast majority of tweets were overwhelmingly positive towards China.

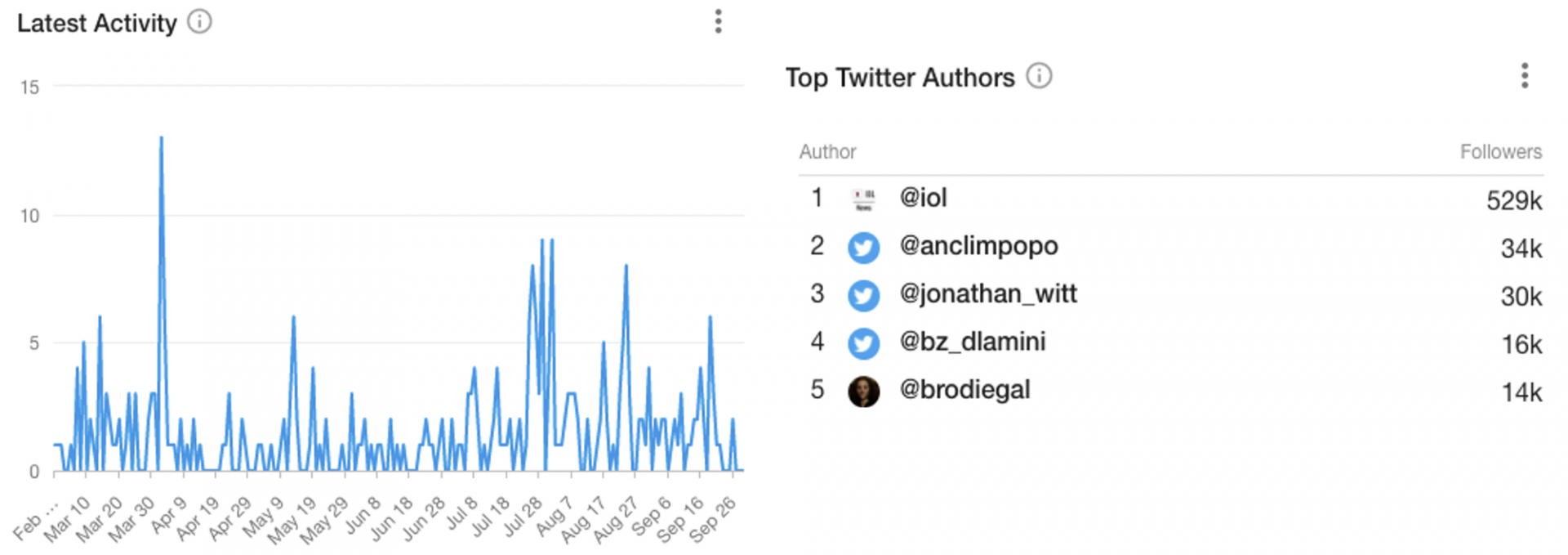

A social media meta-analysis reveals that Chinese efforts may have been successful in elevating the “COVID politicization” narrative in South African social media. According to a DFRLab query using Meltwater, mentions of “COVID politicization” (or “politicisation)” by Twitter accounts with profiles indicating that they are based in South Africa increased by about 91 percent between March 31, 2021, and September 30, 2021, with peaks near March 31 and mid-July, coinciding with China’s diplomatic push of the message. Among Twitter accounts that mentioned the keywords, IOL’s official account (@IOL) had the largest reach, with over 500,000 followers on the platform.

China leverages relationship with IOL to spread COVID-19 conspiracy theory

In addition to the politicization narrative, in the early days of the pandemic Chinese state actors began to circulate a false narrative claiming that COVID-19 originated in Fort Detrick, a US military base in Maryland. The DFRLab wrote about the initial spread of the Fort Detrick conspiracy as a part of its report Weaponized: How rumors about COVID-19’s origins led to a narrative arms race. Following the release of the March 2021 WHO report and the subsequent proposals for a second WHO investigation, China renewed its efforts to promote the Fort Detrick conspiracy theory.

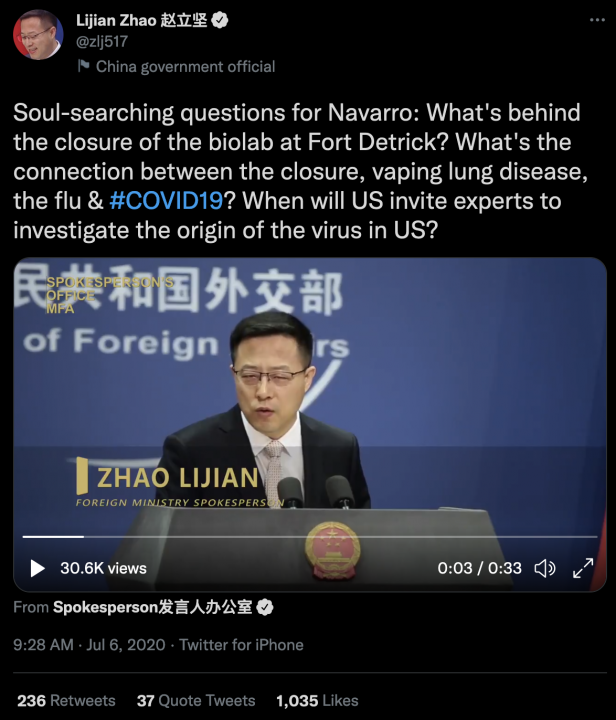

For instance, on July 6, 2020, spokesperson Zhao tweeted: “What’s behind the closure of the biolab at Fort Detrick? When will US invite experts to investigate the origin of the virus in US?” Chinese state television even aired a special report titled “The Dark History behind Fort Detrick” that detailed actual containment breaches at the lab in 2019 to bolster allegations that it was also the potential “leak site” for COVID-19. While the lab was temporarily shut down over problems with the disposal of hazardous materials, the accusations that Fort Detrick is a potential origin site for COVID-19 are unsubstantiated.

An analysis of news articles, Chinese state narratives, and social media activity during the peak of China’s retaliation over the WHO report (July through September 2021) showed that China potentially leveraged its position in the South African media sphere to manipulate the local media environment and give credence to the Fort Detrick conspiracy theory, both within South Africa and in the broader international environment. Coordination between the Chinese consulate in South Africa, China-funded news organizations, and Chinese state media sought to push the Fort Detrick conspiracy theory anew and cast doubt on China as the original source of the COVID-19 virus.

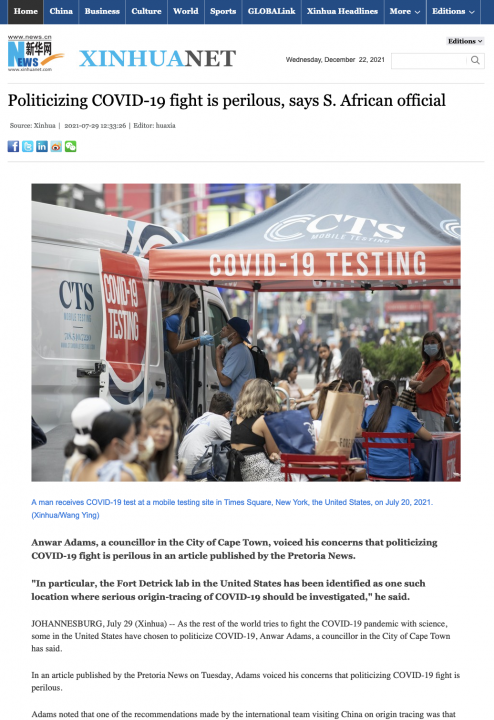

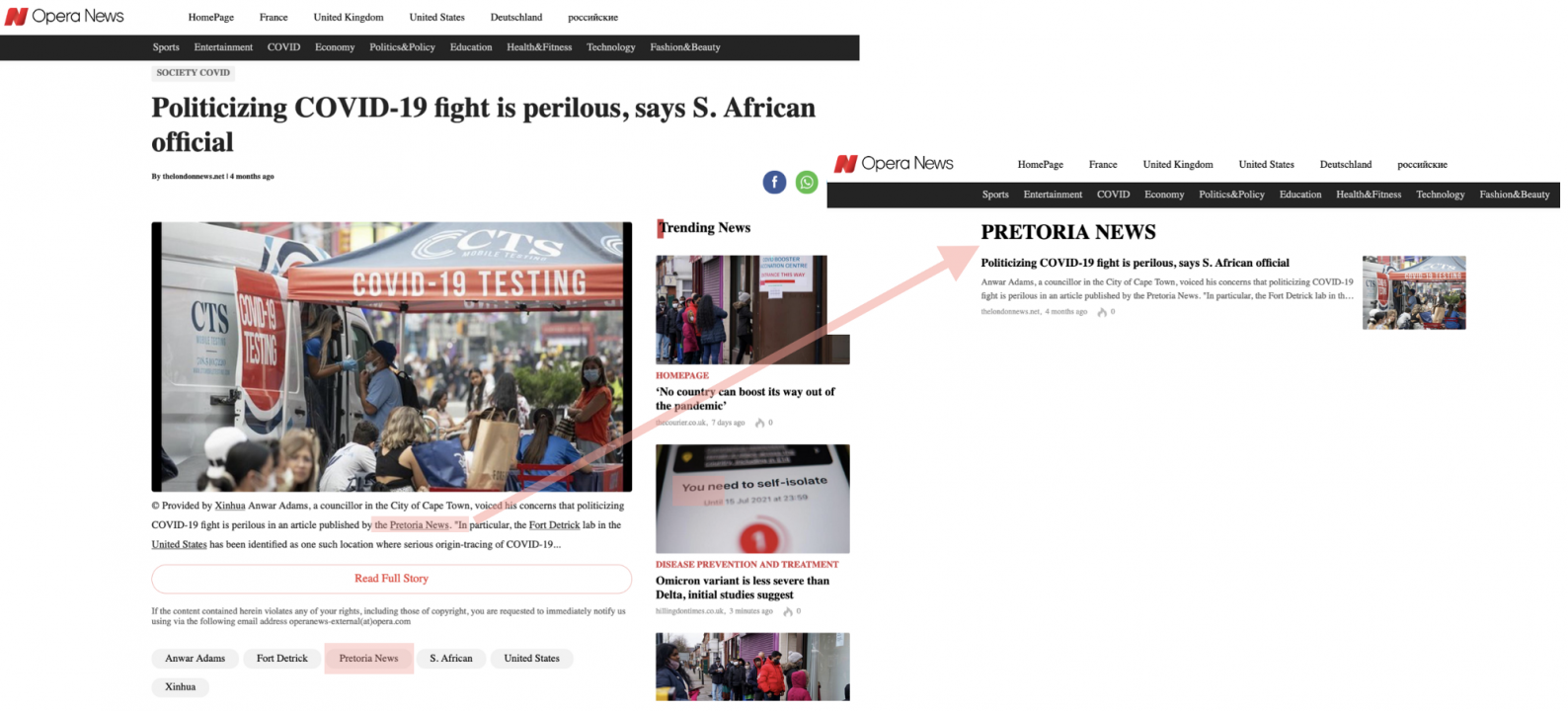

For example, on July 28, IOL published an opinion article titled “Politicizing Covid-19 fight is perilous,” written by Anwar Adams, a councilor in the City of Cape Town, in which the author states, “the continuous politicization of origin-tracing, the propaganda against China…all point to one thing: the US has something to hide.” He goes on to mention Fort Detrick at length, but largely uses it as a means of attacking the WHO and its supposed beneficial treatment of the United States (by not investigating Fort Detrick) while attacking China (by investigating the Wuhan lab). Anwar, for his part, has repeatedly demonstrated extreme regard for China, for example, by participating in an event co-hosted by IOL and Beijing Review, which falls under the China International Publishing Group that itself is under the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department, or pushing for positive relations publicly.

Chinese state media, including People’s Daily, China Daily, and Xinhua, picked up and promoted Adams’ article in their English-language editions, further editorializing and elevating the Fort Detrick narrative. Though Adams mentioned Fort Detrick in his original article, China Daily’s article claimed: “Anwar Adams, a councilor in Cape Town, South Africa, said an investigation should be conducted into the Fort Detrick lab to determine the origin of SARS-CoV-2, given that the biosafety incidents that occurred at the lab coincided with the start of COVID-19 outbreaks.” There is no mention of “biosafety” in Adams’ original op-ed, but it does list a number of problems — both alleged and actual — that happened at the US military research entity.

Similarly, Xinhua quoted Adams as saying: “In particular, the Fort Detrick lab in the United States has been identified as one such location where serious origin-tracing of COVID-19 should be investigated.”

This editorialized summary of Adams’ article was shared widely by Chinese state media, including in an article published by China Daily titled “Netizens Demand Truth on Fort Detrick.”

The Chinese state media’s editorialized takes on Adams’ commentary, which included comments giving further credence to the Fort Detrick conspiracy theory, were then distributed as Xinhua content to local South African news organizations as part of Xinhua’s content agreement.

For example, Opera News, a Chinese-owned news aggregator with around 150 million readers in Africa and which has a content-sharing agreement with Xinhua, published the Chinese state media version of Adams’ article on its website and social media pages. It did so, however, somewhat unclearly. It posted the story with a byline as from “TheLondonNews.net,” an external website to which a user is redirected when clicking the “Read Full Story” prompt. There are, however, a few indications of its provenance, with the “Provided by Xinhua” blurb for the photo and a “Xinhua” tag at the bottom of the post.

The Opera News post also has a tag for Pretoria News and an embedded link for Pretoria News in the excerpt of the TheLondonNews.net piece. When clicking the embedded link, a user is directed to an author page for Pretoria News on Opera News that would, notionally, include links to all of the former outlet’s articles being published to the latter. The only article listed, however, is the one in this case study, the link to which is recursive, sending the user right back to the originating Opera News page.

The full article found on TheLondonNews.net, however, does not feature an embedded link to Pretoria News but includes Xinhua as its byline.

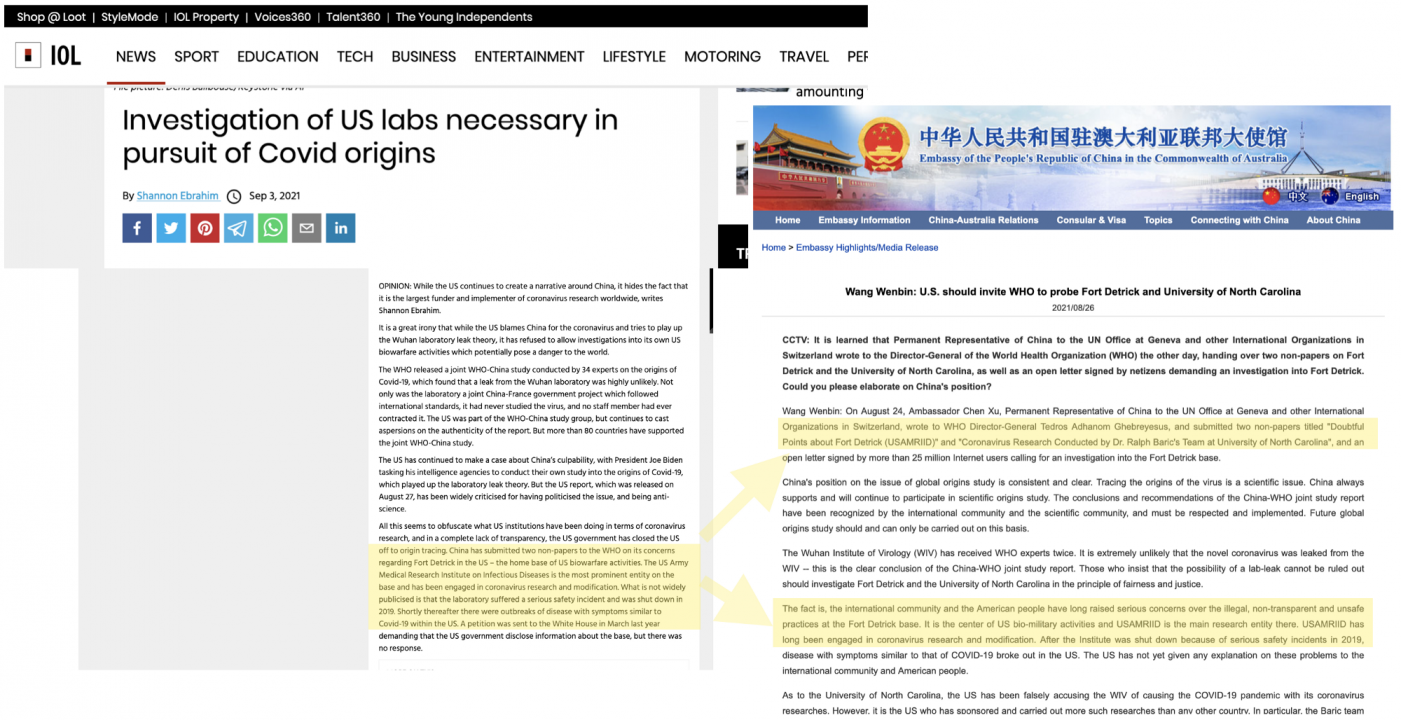

In a similar example, an opinion piece written by IOL editor Shannon Ebrahim and published on the news outlet’s website closely resembled Chinese state talking points on COVID-19 politicization and speculation about Fort Detrick. Ebrahim, like Adams, also has a history of taking a very pro-China stance on political issues. For example, she has supported China’s claims of territorial sovereignty over the contested South China Sea, written on its leadership in the United Nations Security Council, and praised China’s economic contributions to Africa. As mentioned above, IOL is partly owned by Chinese state media. On September 3, 2021, Ebrahim wrote an opinion piece titled: “Probe into US Labs Necessary in Pursuit of COVID Origins,” which includes very similar wording to those pushed by Chinese state officials.

In the September 3 piece, Ebrahim writes:

“China has submitted two non-papers to the WHO on its concerns regarding Fort Detrick in the US — the home base of US biowarfare activities […] What is not widely publicized is that the laboratory suffered a serious safety incident and was shut down in 2019. Shortly thereafter there were outbreaks of disease with symptoms similar to Covid-19 within the US.”

An earlier presser from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, posted August 24, 2021, read similarly:

“[China] submitted two non-papers to the [WHO] […] the Fort Detrick base […] is the center of US bio-military activities and USAMRIID is the main research entity there […] after the Institute was shut down because of serious safety incidents in 2019, disease with symptoms similar to that of COVID-19 broke out in the US.”

Elsewhere, the language in Ebrahim’s article also closely resembled talking points — though not the specific wording — from an August 24 opinion column published in the Cape Times by Lin Jing, Consul General at the PRC Consulate in Cape Town. His article, titled “Trace Covid with Science, Not Politics,” states:

“In May this year, the US President Joe Biden ordered intelligence agencies to ‘redouble’ efforts to investigate the origins of Covid-19, including the theory that it came from a laboratory in China, and report back to him within 90 days. The move has aroused grave concern about the politicization of this scientific issue in the world, and has been firmly opposed by global scientists. By employing intelligence personnel, setting a deadline, and even presetting results, it has been laid bare that the US will frame and discredit China by any foul means in the name of investigation of virus origins.”

While Ebrahim’s article reads similarly:

“The US has continued to make a case about China’s culpability, with President Joe Biden tasking his intelligence agencies to conduct their own study into the origins of Covid-19, which played up the laboratory leak theory. But the US report, which was released on August 27, has been widely criticised for having politicised the issue, and being anti-science.”

In a similar fashion to the Anwar Adams piece, Ebrahim’s essay was picked up, editorialized, and promoted by Chinese state media. A September 10 People’s Daily feature on Ebrahim’s essay reads: “Investigation of US labs necessary for COVID-19 origins tracing: S. African media.” In using the suffix “S. African media,” the title of the article implies that the call for an investigation into Fort Detrick is supported generally by many entities in South African media rather than representing the opinion of a single author in a China-funded outlet. This is a known tactic of China’s, whereby state media will co-opt outside voices or “foreign experts” as a means to gain legitimacy for the narratives it promotes or will at times misrepresent commentary as representative of broader public opinion. The Chinese consulate in Cape Town also promoted Ebrahim’s article on its webpage the day it was published.

Conclusion

The case study above shows evidence of a recursive process in which Chinese state sources push a particular narrative, reports from China-funded local news sources like IOL subsequently amplify it under their own banners and bylines, and then Chinese state media editorializes these local news reports before feeding them back into the South African media ecosystem through its distribution agreements.

The problematic aspect of Chinese state media’s news sharing arrangements with South African sources is not that state media is supplying China-approved content to local media; rather, it is that it warps public discourse by filtering often politically charged issues through a China-centric lens. This is especially problematic for issues like COVID-19 origin tracing and politicization, which resonate deeply with a South African public that is seeing COVID-19 infections at their peak and which has suffered due to a lack of available vaccines. Ironically, the narrative China has pushed attacking COVID “politicization” is in fact seeking to politicize the issue among vulnerable publics.

Cite this case study:

Kenton Thibaut, “China’s COVID-19 messaging makes its way to South Africa,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), December 22, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/chinas-covid-19-messaging-makes-its-way-to-south-africa-f89ff7504be.