Seven steps to spread a conspiracy: How Russia promoted weapons trade allegations

Kremlin sources planted and amplified fake stories about Western weapons destined for Ukraine being sold in Germany

Seven steps to spread a conspiracy: How Russia promoted weapons trade allegations

Share this story

BANNER: A US cavalry scout assigned to 2nd Cavalry Regiment fires a Stinger missile using Man-Portable Air Defense Systems (MANPADs) during a live fire exercise at the NATO Missile Firing Installation (NAMFI) off the coast of Crete, Greece, November 6, 2017.

A conspiracy theory claiming Western-made weapons destined for Ukraine are being illegally sold online can be traced back to the Russian disinformation machine. In this article, the DFRLab examines the seven steps Russia took to disseminate and bring credibility to a conspiracy theory asserting that Ukraine sold Stinger man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) on the dark web, presenting a danger to Europe’s security because they are capable of downing civilian aircrafts.

For Russian audiences, this narrative is likely intended to demonstrate that the Ukrainian government is hypocritical and corrupt for purportedly profiting from the sale of Stinger MANPADS. And by suggesting that military aid to Ukraine could be used against civilians elsewhere in Europe, this narrative is intended to prove to Western audiences that Ukraine is an unreliable and dangerous partner.

The DFRLab has previously covered similar iterations of this narrative.

Step 1 — Build a false foundation

On September 7, 2022, the obscure YouTube and Telegram channel Journalisten Freikorps (“Free Corp of Journalists”) published a six-second video of a Stinger MANPAD lying on the ground. The video description claimed the footage was filmed at the German port of Bremen on July 20, 2022, as Ukrainian military personnel were being arrested for transporting multiple “tubular devices.” The post also claimed the Ukrainian troops were aboard the ship Floriana, sailing under a Ukrainian flag, and bound for Turkey.

In the footage, an authoritative German voice can be heard asking someone to stop filming. Researchers from the Ukrainian fact-checking organization StopFake and the US fact-checking organization Lead Stories found that the audio was copied from an old YouTube video uploaded on January 23, 2022. In addition, while the Floriana is a real vessel, it sails under the Maltese flag rather than the Ukrainian flag. Bremen police confirmed the report was false and that they “did not arrest any Ukrainians who dealt in weapons.”

The Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) conducted a separate investigation into Journalisten Friekorps’s assets and found the organization was connected to Russia by tracing it to an expired Russian e-commerce domain name. The organization also spread anti-Ukraine petitions in Germany that were recently included in a Facebook takedown covered by the DFRLab and promoted other websites aimed at discouraging support for Ukraine. Further analysis from threat intelligence researcher Kyle Ehmke found a connection between Journalisten Friekorps and other pro-Russia websites in German.

The Journalisten Freikorps Telegram channel was created on May 18, 2022; it typically reposts short news stories from local German media outlets. The Journalisten Freikorps YouTube channel was created on August 24, 2022 and links to a non-functioning website.

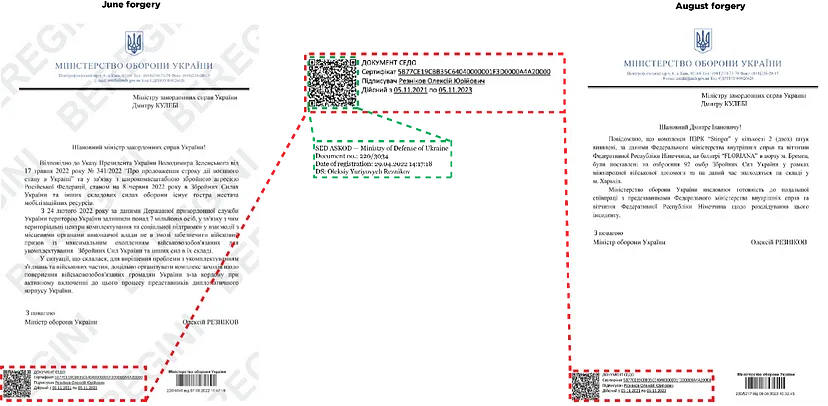

Step 2 — Use forgeries to support a false debunk

The next step in the Russian playbook is providing additional “evidence” to cement the narrative. In this case, a September 7, 2022 article by the fringe Ukrainian publication National Bank of News (NBN) claimed it had fact-checked the story using a letter that turned out to be a forgery. The article, which appeared the same day Journalisten Freikorps published the video to its Telegram and YouTube videos, discussed a Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung interview with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. NBN claimed that Scholz “deliberately” delayed weapons shipments to Ukraine because of the Journalisten Freikorps video. The article then stated that Ukrainian troops were not detained in Germany for transporting weapons, “debunking” the claim using the forged letter.

The letter in question, purportedly written by Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov, was addressed to Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba. It claimed that the Stinger MANPADS identified at the port of Bremen were now in Kharkiv. In the letter, the word “Kharkiv” is written as “Харьків,” which is a combination of the Ukrainian spelling “Харків” and Russian spelling “Харьков.” The letter also used a copy of Reznikov’s digital signature, stolen from another document signed on April 9, 2022; it previously appeared in a September 2022 forged letter documented by the DFRLab.

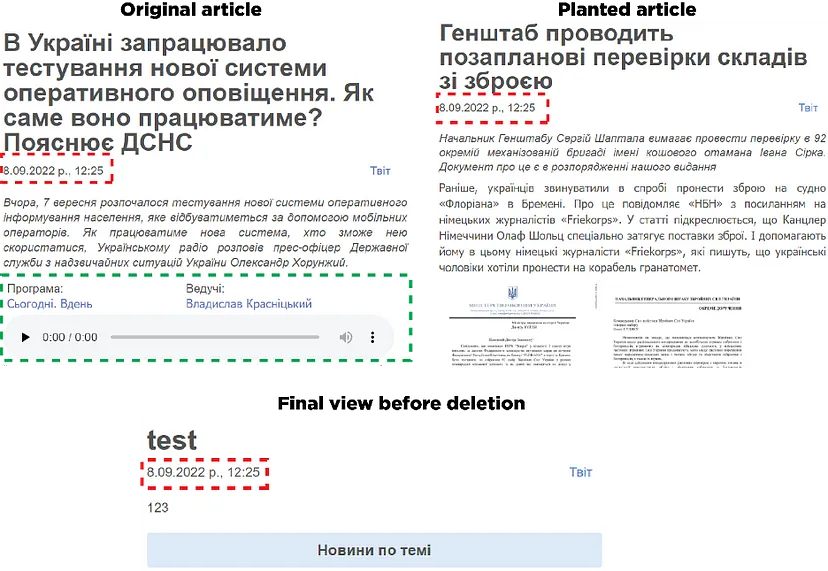

Step 3 — Plant bogus evidence in a credible source

The next day, on September 8, Ukraine’s public radio broadcaster published a story at 12:25pm about the testing of a new emergency notification system. According to archival versions of the piece preserved by the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, at some point in the next three hours, hackers breached the website and replaced the text with a new story titled, “The General Staff conducts unscheduled inspections of warehouses with weapons.” In addition, there is a third version of the story that appeared before the article was taken offline with the title “Test” and the body text “123.” Ukrainian Radio confirmed the breach to the DFRLab.

The inserted story was about Serhiy Shaptala, Chief of the General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, demanding inspections of the 92nd Mechanized Brigade. The article quoted Freikorps and NBN and shared the forged Reznikov letter. The article also included another document, which does not bear any digital signatures. The document sets out an additional “separate assignment” to check on the availability of Stinger systems, resulting from random inspections that purportedly found three missing Stinger MANPADS.

While the style of the hacked article is somewhat similar to the style of Ukrainian Radio, it lacked one essential component — audio. Ukrainian Radio embeds audio clips in its articles, containing excerpts from its broadcasts. The hacked story did not include any audio recordings.

Step 4 — Launder the source of information

The next step in the Russian disinformation playbook is to launder the source of the information by appearing to amplify other coverage. On Telegram, Journalisten Freikorps highlighted the “investigation” of “Ukrainian colleagues” at Ukrainian Radio — e.g., the hacked web page — adding that they “hope for the answers.” The post included a screenshot from a dark web marketplace and claimed that users can order Stinger MANPADS online. Journalisten Freikorps suggested that the dark web shop and the disappearing weapons may be related. The use of the dark web as a scarecrow is a recurring approach that Russian disinformation outlets have relied on since the invasion of Ukraine, as the DFRLab has previously reported. The DFRLab attempted to access the dark web marketplace, but the site was unreachable at the time.

Later, Journalisten Freikorps published another post that said Ukrainian Telegram groups are offering to pay people to place dark web orders. The claim appears to have originated from a single Telegram account that published two posts in a Telegram group, one in English and one in Ukrainian, offering payment for dark web orders. However, Ukrainian moderators immediately deleted the post and kicked the account out of the group. The account is no longer active on Telegram.

Journalisten Freikorps also published a screenshot of a private chat allegedly sent to them by a German student who claims to have exposed the dark web marketplace and alerted local police in Dresden. The DFRLab attempted to verify the student’s claim with Dresden police, who told the DFRLab, “the occurence you are refering to ist [sic] know to Polizeidirektion Dresden and is currently under investigation from the Staatsschutz department of Dresden Police.”

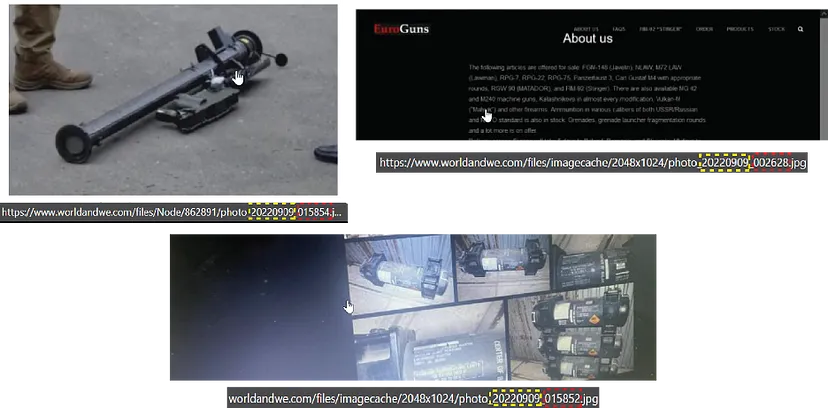

Step 5 — Time the release

Image metadata suggests that some consideration also went into timing the release of the disinformation campaign materials. A key website in the operation is World and We, a blogging platform where registered users can publish stories. On September 17, it published a story about the Stinger MANPADS and said that Ukraine “has already been repeatedly convicted of outright lies,” so any denials should be ignored. The article also claimed Europe’s security was under threat. The article cited the Journalisten Freikorps’ Telegram channel and included images of the forged letters and the supposed dark web marketplace. Three image file names contain the date “20220909” and times that range from 12:26:28 a.m. to 1:58:54 a.m. This is a standard naming format many computers use when taking a screenshot or saving a file. The images published on the website do not follow a unified naming system, suggesting images maintain the file name provided by the author. The file name suggests that preparations were underway for this article as early as September 9. However, it was published eight days later. While the reason for this delay is unknown, it is worth noting that during this period the Ukrainian army was conducting a counteroffensive in Kharkiv oblast that was making headlines.

On September 14, the story also appeared on the German website Weltexpress, which accepts payment for coverage. The outlet has previously published pro-Kremlin narratives, including an article that blamed Ukraine for the Bucha massacre. Weltexpress cited the NBN article and the “evidence” provided by Journalisten Friekorps. After Russian media began promoting the narrative), the Weltexpress article was amplified by Olga Petersen, a Russian-born German politician with the Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) party. In her post, Petersen said she would ask the Hamburg senate to investigate. AfD is known to have links with Russia.

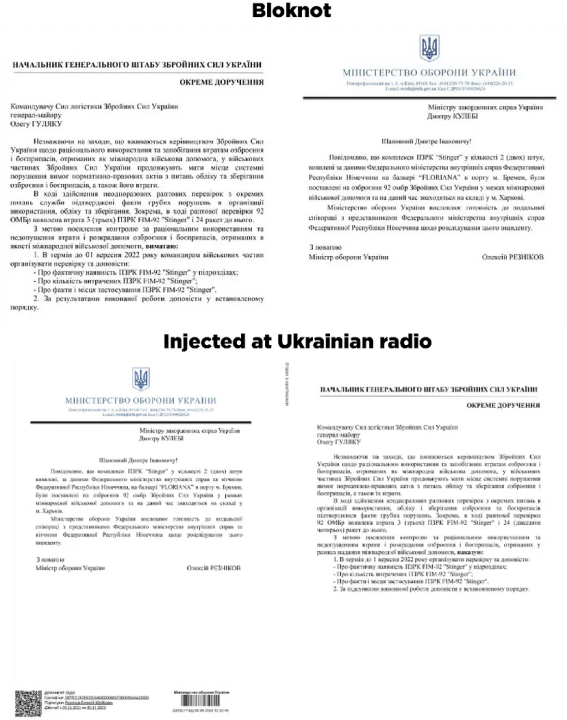

Step 6 –Pro-Kremlin sources pick up the baton

On September 16, the pro-Russia YouTuber Vladimir Gorbovskiy published the Stinger video on his Telegram channel. He claimed that German authorities had contacted Ukrainian officials to discuss missing weapons and Ukraine responded that it was storing the weapons. He then hypothesized that the weapons would be used against civilian aircrafts in Europe. Another Telegram channel found a Bremen police statement regarding the theft of electronic equipment and falsely interpreted it as being related to the Stinger operation.

On September 17, World and We’s Telegram channel published the Stinger video and asked, “Germans, have Lufthansa planes fallen yet?” A few hours later, the abovementioned World and We article was published. The story was republished verbatim by the pro-Russia fringe media outlet Naspravdi.info, while a slightly edited version appeared on the pro-Kremlin website Bloknot. Bloknot also published a followup story that claimed people in the West were protesting military aid to Ukraine. This story included one image with “2022–09–08” in its name. The article also included the two documents shared in the hacked Ukrainian Radio story; however, it shared the documents in reverse order. This is noteworthy because the two documents were shared as a single image file. The Bloknot version also removed the digital signature. A comparison of the documents revealed minor differences in the document that does not bear a letterhead, indicating the text was slightly edited.

The story also circulated in mainstream pro-Kremlin media. The tabloids Moscow Komsomolets and Komsomolet’s Pravda repeated the claim that Ukrainians had been detained in Germany for trading weapons and amplified the narrative that a German student discovered the illegal marketplace. They also cited anonymous “local media” to claim that the weapons were intended for the Kharkiv counteroffensive.

The next day, the story appeared on Channel One Russia. It then reached Twitter, where it was shared by Dmitry Polyanskiy, the Deputy Permanent Representative of Russia to the United Nations. The story also made waves on Russian social media platform VK. The posts appeared on both personal pages and groups, including one dedicated to the city of Boston. The VK posts mostly cited the archived Ukrainian Radio article as evidence.

Step 7 — Prepare some “analysis” and translate it into English

War On Fakes, a pro-Kremlin disinformation outlet masquerading as a fact-checking organization, also reported on the claim, first in Russian, and a few hours later in English. The article replicates much of the World and We article, cites the NBN article, and includes a screenshot of the Ukrainian Radio article. The article claims that “Western arms were literally flooding from Ukraine to different countries of the world,” and concludes that Ukraine should not be trusted. The article was shared on Facebook by the Russian Embassy of New Zealand.

Cite this case study:

Roman Osadchuk, “Seven steps to spread a conspiracy: How Russia promoted weapons trade allegations,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), March 9, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/03/09/seven-steps-to-spread-a-conspiracy-how-russia-promoted-weapons-trade-allegations/.