How the Venezuelan regime weaponized video and messaging apps to persecute dissidents

Maduro promotes app that encourages users to report critics of the regime amid widespread demands for election transparency

How the Venezuelan regime weaponized video and messaging apps to persecute dissidents

Share this story

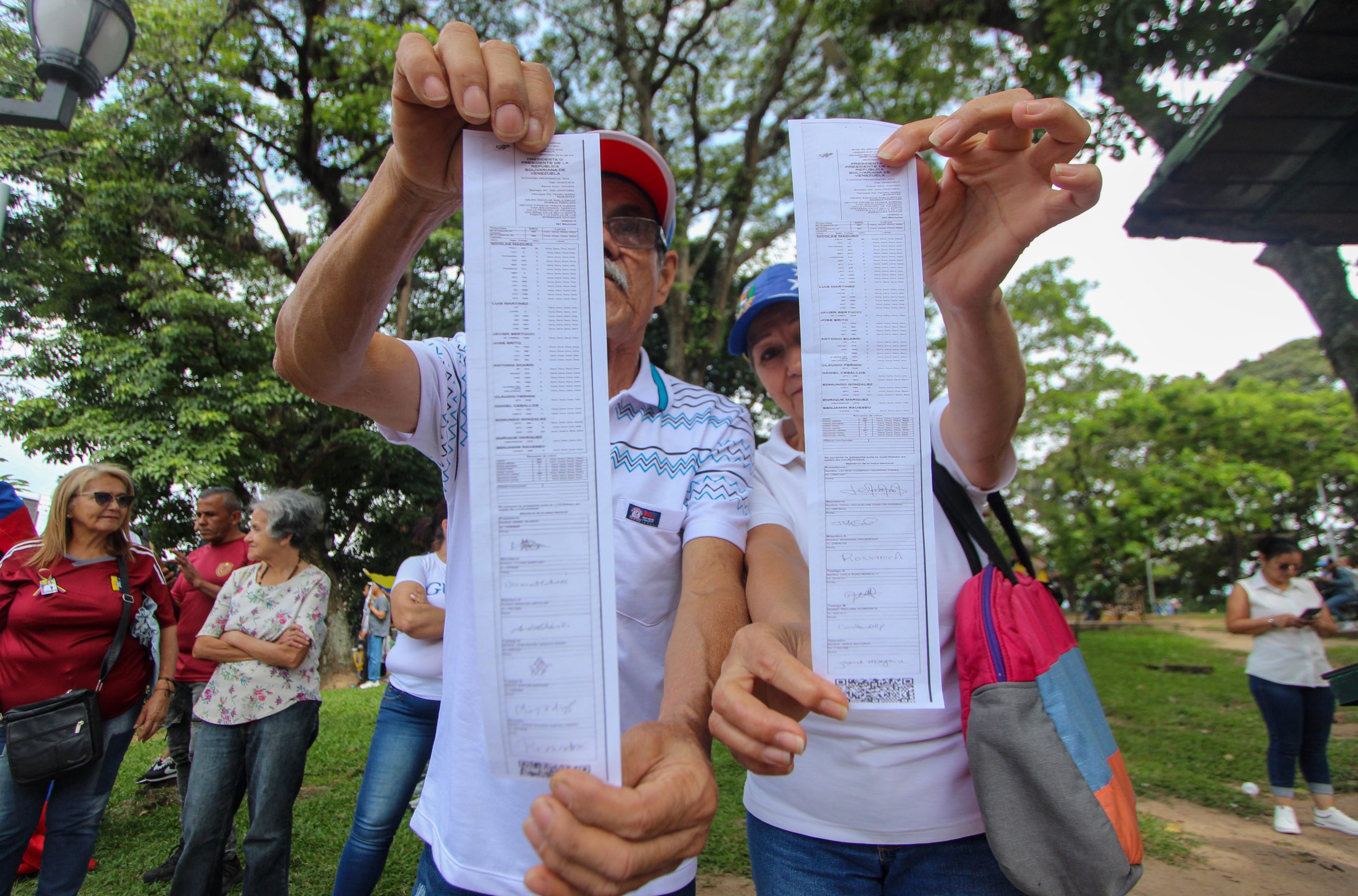

BANNER: Demonstrators hold copies of the voting records during a rally in San Cristobal, Venezuela, on August 17, 2024. (Source: Jorge Mantilla/NurPhoto via Reuters)

Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro is trying to control online narratives and suppress protests in order to maintain power after his regime claimed victory and accredited disputed electoral results, sparking domestic unrest and a decline in international support. In the face of growing claims of electoral fraud, Maduro has relied on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, WhatsApp, and VENapp to promote himself and encourage the persecution and violent repression of opposition demonstrators.

At the time of writing, the election results were opaque and unsettled. On July 29, 2024, the day after the election, Maduro’s National Electoral Council (CNE) announced that Maduro had won by around 700,000 votes, beating opposition candidate Edmundo González Urrutia. On August 2, the CNE confirmed Maduro as the president-elect with a margin of over one million votes. However, the results were disputed by the opposition, which presented tally sheets from polling stations that indicated González had won the election by a margin of nearly four million votes. The United Nations (UN) deployed a panel of experts to Venezuela, who shared an interim report that stated the evidence submitted to the UN by the CNE does not meet the legal requirements. On September 12, the United States levied sanctions against Maduro’s allies, citing electoral fraud. “Maduro and his representatives have falsely claimed victory while repressing and intimidating the democratic opposition in an illegitimate attempt to cling to power by force,” the announcement read.

The disputed election results have led to widespread protests in Venezuela, which have been met with violent repression by Maduro’s security forces, including police and armed civilian groups known as “colectivos.” Patrolling drones that are part of the nation’s enhanced digital repression toolkit were also deployed to surveil Venezuelan cities.

The Observatorio Venezolano de Conflictividad Social and the Centro para los Defensores y la Justicia reported on August 9 that 915 protests occurred in Venezuela between July 29-30, 2024. The organizations indicated that 138 of these protests faced some form of repression, primarily by colectivos, resulting in twenty-one deaths, mostly from gunfire. The UN reported that between July 28 and August 8, more than 2,400 people were detained, and twenty-three were killed. The UN described the regime’s actions as arbitrary detentions and enforced disappearances that violate the rights of the victims, which include more than one hundred minors detained under irregular procedures.

Operation Knock Knock

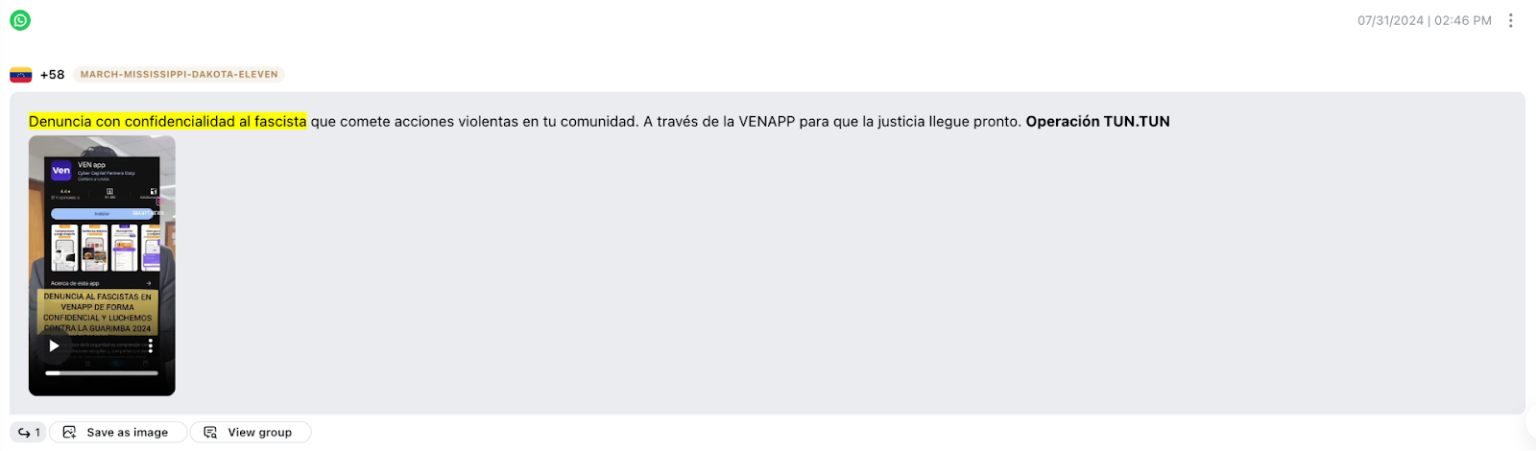

Beyond the violent repression targeting street protests, Maduro has activated his communications apparatus to silence protests taking place on digital platforms. In the weeks following the election, the Maduro regime implemented “Operación Tun Tun” (“Operation Knock Knock”). This repressive strategy uses multiple digital platforms to target independent media, human rights defenders, activists, and opposition party members through coordinated online campaigns of stigmatization and persecution. “Operation Knock Knock” has resulted in thousands of arrests and reports of judicial violations. Moreover, Maduro’s security forces and pro-Maduro accounts have distributed videos in which alleged detainees incriminate themselves, ask Maduro for forgiveness, and blame opposition leaders for hiring them. These videos include memes mocking the detainees or horror movie soundtracks.

Operation Knock Knock employs previously documented tactics, such as recording seemingly forced confessions. For years, the Maduro regime has maintained the practice of recording prisoners and violating their rights to due process. Maduro officials and supporters have previously amplified regime-produced videos that show political prisoners confessing to crimes, possibly under duress, as exemplified in the case of Roland Carreño. In addition, we observed the resurgence of a tactic that encourages party supporters to expose their neighbors. Previously, the regime used online platforms to encourage citizens to report migrants returning to Venezuela amid the social and economic crises brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic in the countries where they had sought refuge, labeling these individuals as “biological weapons.”

Facilitating digital persecution through VenApp

Amid the amplification of “Operation Knock Knock,” Maduro-controlled institutions and pro-Maduro accounts promoted on social media a directive issued by Maduro to use an application called VenApp to submit reports on dissenting individuals. The reports gathered personal information, including addresses, of demonstrators and opposition electoral witnesses in order to facilitate their arrests.

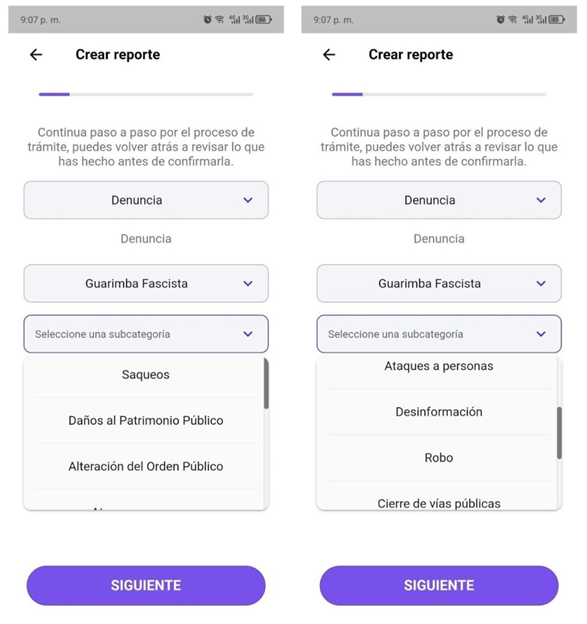

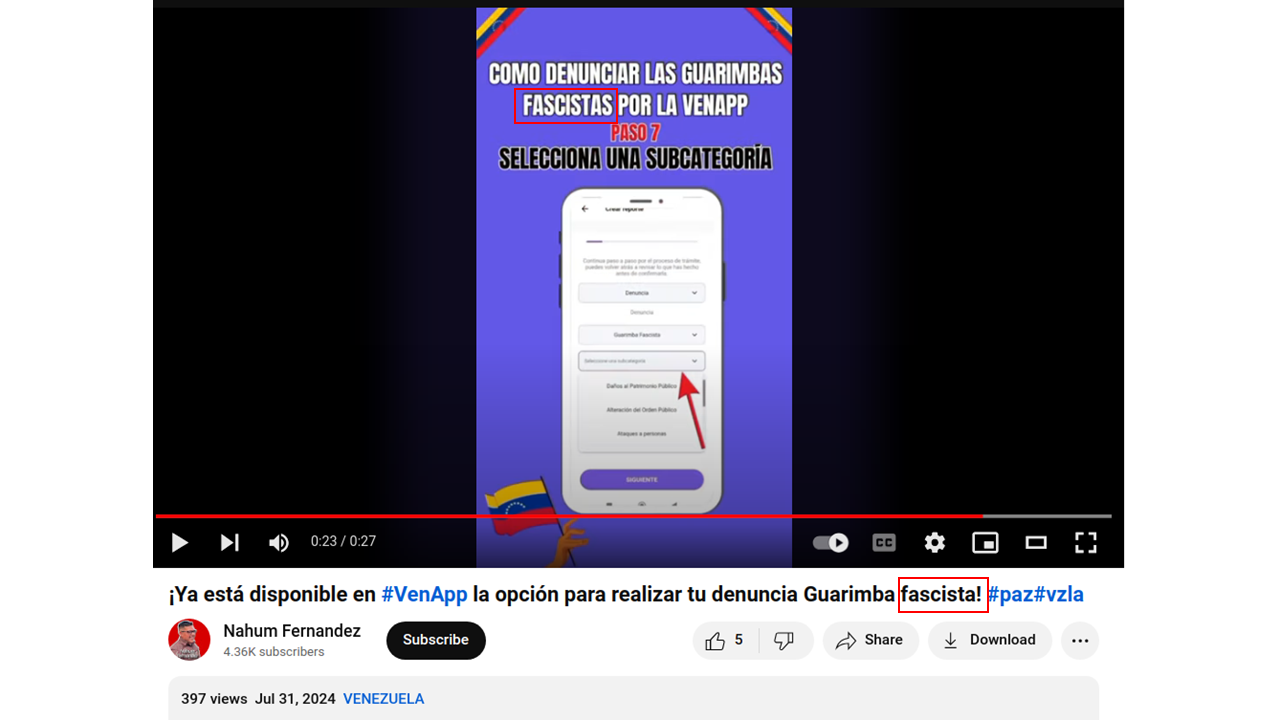

VenApp was initially created for internal use by Maduro’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) during the 2022 gubernatorial campaign. Later, the app was altered to serve as a platform to report failures in public services. After the election, Maduro announced a new update to the app that introduced a function to create reports against “Guarimbas Fascistas,” a pejorative and stigmatizing term that the regime uses against protestors.

The DFRLab’s July 2024 report, Venezuela: A playbook for digital repression, warned that VenApp “could become a dangerous reporting tool against political activities such as opposition door-to-door campaigning or citizen assemblies. Government and police officers could use geolocation to locate protest participants.” This threat has been realized.

On July 31, Apple and Google removed VenApp from their application stores for infringement of the terms of use. In response, regime supporters and authorities promoted other channels to send the reports, such as WhatsApp or social media accounts. Despite the app store bans, the VenApp APK file continues to be distributed via Telegram and various online forums, enabling the app to be downloaded to Android devices.

Amplifying Maduro’s claims on YouTube

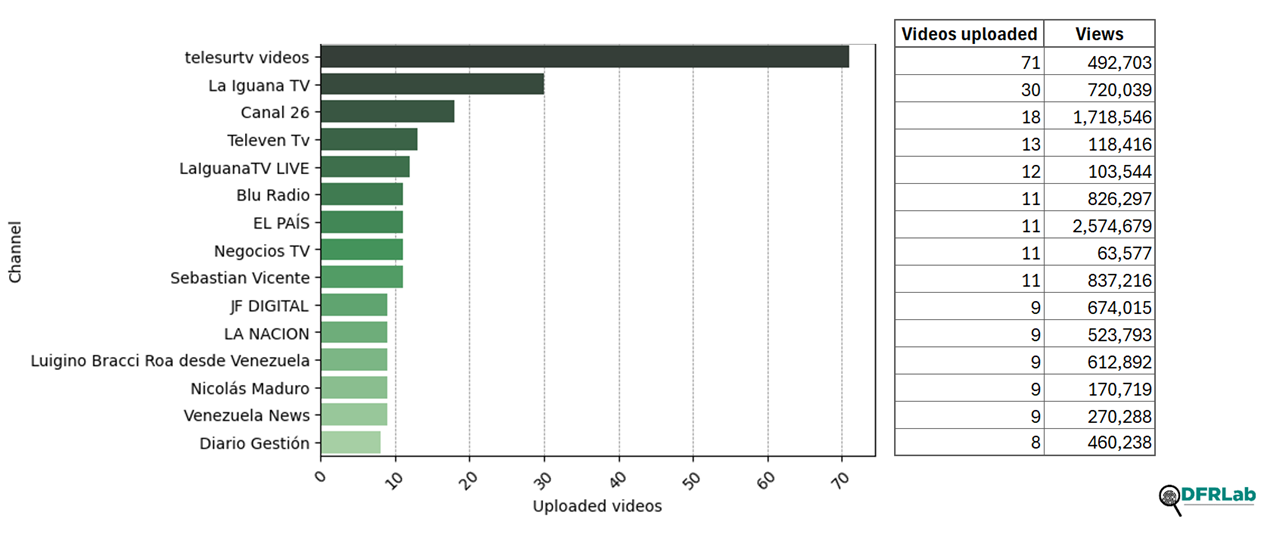

To assess how Maduro’s strategy of digital repression was amplified, promoted, and coordinated, the DFRLab conducted advanced searches on video platforms YouTube and TikTok using keywords such as “fascist squads,” “Operation Tun Tun,” and “VenApp.” On TikTok, we analyzed four accounts that appeared in text and advanced image searches as the most active in sharing the regime’s propaganda and the personal information of detainees and protesters between July 28 and August 9, 2024. On YouTube, we identified 1,564 videos published between July 28 and August 4, 2024. We examined the fifteen most active channels and deconflicted those sharing neutral news coverage, leaving six channels, all of which were linked or aligned with the regime. For example, Telesurtv, a channel belonging to the Maduro-controlled regional broadcaster Telesur, published seventy-one videos, the highest number of videos in our dataset, receiving more than 492,000 views. The five other most active channels included Maduro’s official channel, Nicolás Maduro, La Iguana TV, Venezuela News, and Luigino Bracci Roa desde Venezuela, which published a combined total of sixty-nine videos garnering nearly 1.9 million views.

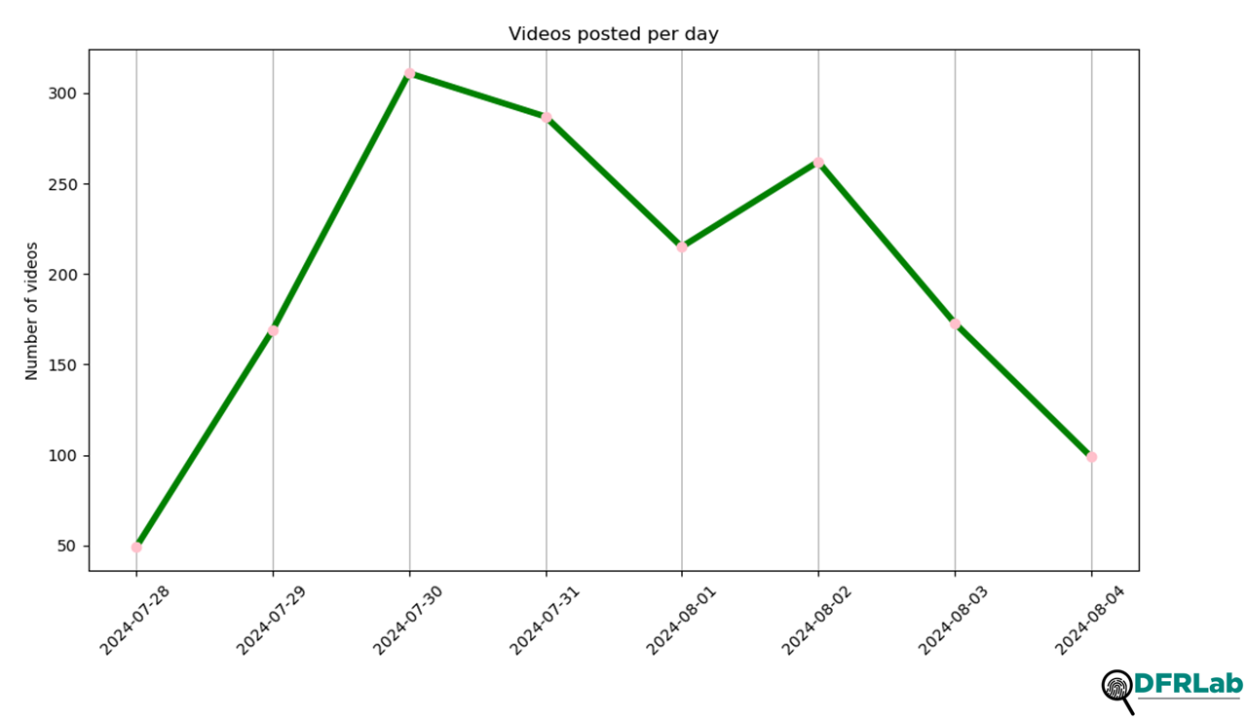

The videos published by the pro-regime channels echoed Maduro’s narrative, framing the protests as part of a coup and destabilization effort led by “the global far-right” or opposition leaders, with no mention of the concerns regarding the lack of transparency in the election results. Additionally, the accounts also shared Maduro’s televised broadcasts where he stigmatized protesters and the opposition as “terrorists” or “fascists.” In a video shared by Luigino Bracci Roa desde Venezuela, Maduro promoted the VenApp application “to report criminal and delinquent groups with complete privacy and confidentiality.” Between July 30-31, when Maduro began promoting VenApp as a medium to target protesters, posting behavior surged, with more than 600 videos published during this period.

In addition to the channels belonging to officials or media aligned with Maduro, the regime’s narratives were also broadcast by individual accounts, however these videos received far fewer views. For instance, RalitoDigital, an account previously associated with regime-affiliated campaigns on different platforms, shared a video with the phrase “any spark that ignites, any spark that gets extinguished” in the title. Maduro and former President Hugo Chavez have used this phrase for years to incite violent repression against protesters.

Meanwhile, PSUV member Nahum Fernández published a YouTube video explaining step-by-step how to use VenApp to report protesters, whom he referred to as “fascists.”

On August 9, the channel Con El Mazo Dando, which belongs to the regime’s second-in-command Diosdado Cabello, was removed from YouTube. This occurred despite Cabello’s announcement just two days prior that YouTube had recognized his channel for reaching 100,000 subscribers. YouTube has previously suspended channels associated with media outlets closely tied to Maduro and his allies.

In parallel, the regime recently expressed reluctance to continue using TikTok, a platform on which Maduro campaigned for more than two years, trying unsuccessfully to gain support from Venezuelan youth. Independent commentators indicated that the reason for moving away from TikTok was the backlash Maduro received from influencers and users.

A more explicit persecution on TikTok

Similarly to YouTube, TikTok users have posted videos featuring audio of Maduro calling on citizens to report the identities and location of demonstrators in the context of “Operation Knock Knock.”

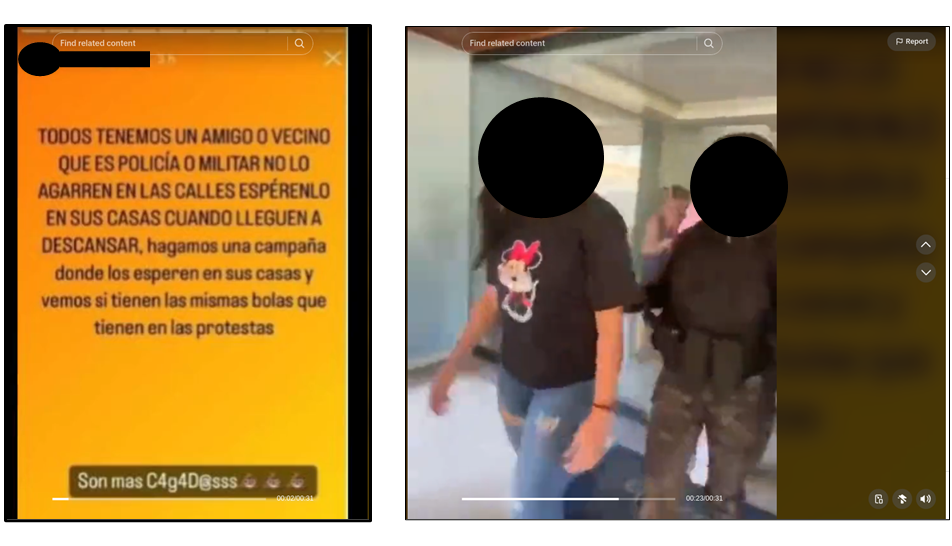

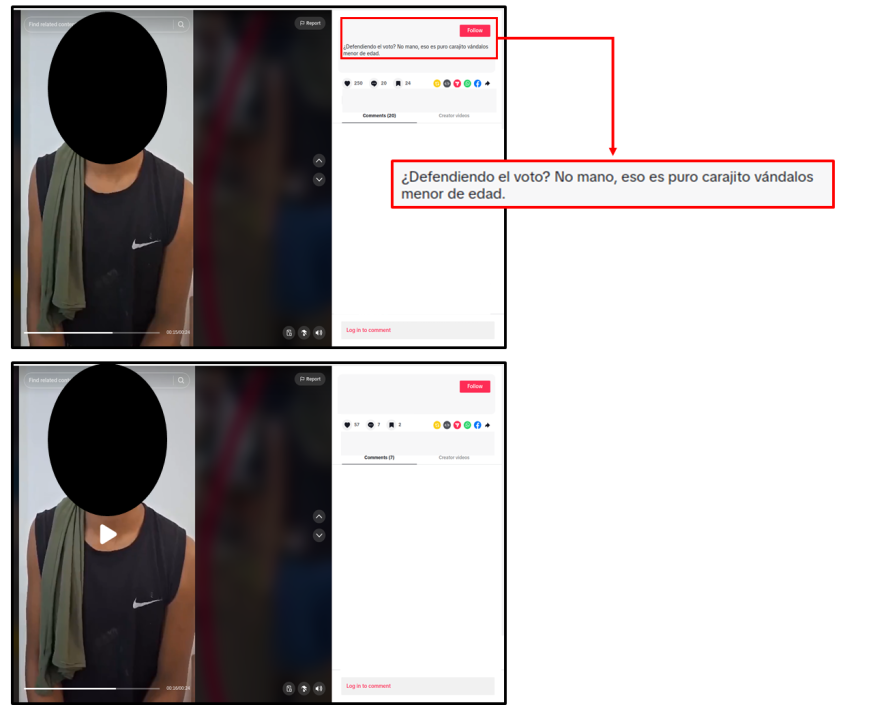

Four identified TikTok accounts uploaded nearly forty posts; two of those accounts belonged to the Venezuelan regime’s security corps, and two belonged to users who primarily publish pro-regime content. The official accounts belong to the National Bolivarian Armed Forces of Venezuela and the Anti-Drug Division of the Police Force. Throughout the course of our investigation, the Anti-Drug Division account was removed from TikTok. The forty identified posts contained videos and photos showing people being detained and later incriminating themselves on camera for supposed crimes committed while demonstrating against Maduro. Some of the videos also included memes mocking the detainees. Other videos included screenshots of social media posts advocating against Maduro or regime institutions, followed by images of the supposed authors under arrest.

The account belonging to the Anti-Drug Division of the Police Force was the most active in sharing photos containing “wanted” notices or videos of alleged protesters incriminating themselves. Between July 28 and August 9, the account uploaded twenty-four posts that garnered nearly 284,000 views. The content featured individuals seemingly revealing their full names and identification numbers, admitting to alleged crimes, retracting their actions, or blaming opposition leaders like Maria Corina Machado for being the masterminds behind the protests.

An analysis of the videos posted by the Anti-Drug Division of the Police Force revealed that the narratives of stigmatization and persecution developed in two stages. The first fifteen posts, published between July 30 and August 2, contained videos and photos with “wanted” posters seeking personal information about alleged protesters and opposition activists and accusing some of being involved in drug trafficking. After August 2, the posts primarily featured videos of detainees supposedly confessing and asking for forgiveness. Additionally, on at least three occasions, at least one of the two identified supporter accounts published the same video as the Anti-Drug Division account. Throughout the course of our investigation, one video was removed from the TikTok page of one of the supporter accounts.

The Bolivarian National Armed Forces and the two supporter accounts posted a total of seventeen videos promoting persecution and sharing photos of alleged detainees. These videos collectively received over 111,000 views.

The DFRLab refrained from publishing links or channel handles as some individuals appear to be minors. Others appear with visible injuries, and it is difficult to determine whether the injuries were inflicted before or during detention.

This report was produced as part of the joint Venezuelan election monitoring implemented by ProBox, DDIA, and the Atlantic Council’s DFRLab. See the Spanish and English reports.

Cite this case study:

Daniel Suárez Pérez and Iria Puyosa, “How the Venezuelan regime weaponized video and messaging apps to persecute dissidents,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), September 23, 2024, https://dfrlab.org/2024/09/23/venezuela-weaponizes-apps/.