Brazil’s electoral deepfake law tested as AI-generated content targeted local elections

For the first time, Brazil held elections under new regulations prohibiting deepfakes, yet dozens of instances proliferated prior to voting

Brazil’s electoral deepfake law tested as AI-generated content targeted local elections

Banner: AI-manipulated video shared by Salvador mayoral candidate Bruno Reis, showing him dance to his campaign song in different locations. (Source: @brunoreisba)

Brazil held municipal elections in October 2024 under strict new electoral regulations that banned campaigns from using unlabeled AI-generated content in an effort to combat AI-fueled disinformation. The DFRLab monitored the electoral landscape over a six-month period and found evidence of deepfakes circulating in various formats, including images, audio, and video across different platforms, like Facebook, Instagram, X, TikTok, YouTube and WhatsApp. We identified seventy-eight instances of content directly related to local candidates that was either confirmed or alleged to be synthetic, highlighting generative AI’s potential to compromise the integrity of the electoral landscape.

Almost 80 percent of the identified cases fit into at least one of six tactics:

- Pornography deepfakes targeting female candidates

- Manipulated content falsely accusing candidates of crimes such as corruption, bribery, or misconduct

- Impersonation of media figures and news reports to spread false information to affect the reputation of a candidate

- Appropriation of images of prominent Brazilian politicians to either falsely support a candidate or undermine someone’s candidacy

- AI-manipulated content about political events, such as dates of rallies, or the number of candidates or parties on a ballot

- Satirical and humorous political deepfakes

We also identified a single instance of a deepfake scam. In the remaining 20 percent of cases, the DFRLab could not access the raw materials to conduct analysis.

The use of AI to enable disinformation, especially the production of deepfakes, was a primary concern of Brazilian electoral authorities ahead of the October 2024 municipal elections, in which 150 million people voted to elect mayors, councilors, and other local officials across 5,568 municipalities. In February 2024, Brazil’s Superior Electoral Court, the body responsible for organizing and monitoring the election, approved a resolution regulating the use of AI during the 2024 electoral campaign.

As we reported in our prior analysis of the new rules, the regulations mandated that campaigns be transparent when disseminating materials manipulated by AI tools, such as improvements in image or audio quality, the production of graphical elements, or visual montages. Campaigns were thus required to clearly inform audiences when they used AI to create or edit electoral content, including specifying the tool employed. Additionally, the regulations prohibited using AI to produce false content or deepfakes intended to harm or favor a candidate. In cases in which the electoral court could prove that a candidate’s campaign used any of these tactics, it had the power to revoke their electoral registration.

Notably, these rules applied to generative media created by the campaigns themselves. Generative AI content produced by individuals not linked to parties, candidates, or campaigns is subject to civil and criminal laws.

Monitoring the online information landscape

To better understand the impact of the AI regulations, as well as the tactics, formats, and frequency of political deepfakes during Brazil’s municipal elections, the DFRLab monitored social networks, websites, blogs, and public messaging apps from May 1 to October 27, 2024. The research timeline comprised the pre-campaign period (May 1 to August 15), the leadup to the first round of voting (August 16 to October 6), and the runoff vote (from October 7 to October 27).

The investigation aimed to identify online user discussions or reports referencing political deepfakes. The monitoring combined a range of tools and methodologies to identify mentions of the keywords “deepfake” and “artificial intelligence” in Portuguese, along with variations in spelling and plural forms.

The research operated under two premises. First, there is currently no reliable and efficient method to systematically collect metadata and analyze synthetic content, especially across different platforms. Second, a major challenge is that producers of deepfakes intending to spread disinformation or cause harm would not openly identify their work as deepfakes; this makes detection even more difficult, especially in environments prone to a deluge of content, such as elections. Given these limitations, user discussions or reports referencing political deepfakes – either confirmed or alleged – are a valuable method to find instances of deepfakes already in the public domain.

The investigation used Google Alerts to track mentions of political deepfakes on websites and blogs in Portuguese, and the social media monitoring tool Meltwater Explore to identify discussions surrounding the topics of “deepfake” and “artificial intelligence” on X from May 1 to October 27. Notably, the X platform was temporarily banned in Brazil during the electoral campaign. Applying the same keywords on Meta, we also analyzed posts and political ads on Facebook and Instagram.

Additionally, we analyzed messages from 290 Brazil-based public groups on WhatsApp dedicated to political discussions, as well as the activity of 815 official profiles of mayoral candidates and pre-candidates for Brazilian state capitals on X, Instagram, Facebook, Telegram, and YouTube. This analysis was conducted by creating a dashboard of relevant accounts on the social media monitoring tool Junkipedia.

More details regarding our analytical approach can be found in our overview of our research methods, their strengths and limitations, and the challenges of identifying deepfakes, published in conjunction with Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s NetLab UFRJ on October 2, 2024.

Tactics and formats

The DFRLab identified 78 confirmed or alleged cases of political deepfakes from May 1 to October 27. Six retroactive cases from December 2023 to April 2024 emerged during data collection but were not included in the final list of incidents, as they fell outside the electoral calendar’s time parameters.

Of these 78 instances, 65 of them targeted mayoral candidates. The remaining 13 instances comprised nine cases involved misleading information about councilor candidates four cases related to deputy mayoral candidates. These instances took place in 67 cities, with São Paulo, the largest city in Latin America, leading the list with eight cases.

The deepfakes appeared in various formats, with 48 videos, 17 audio clips, and six images. The DFRLab could not confirm the original format of the content in seven cases.

WhatsApp was the main platform on which the alleged political deepfakes were disseminated, with 25 incidents. Instagram ranked second with 13 incidents, followed by TikTok with three, X with two, and YouTube with one. Once the content was published, it often spread to other platforms.

In terms of narratives, twenty-seven incidents referred to cases in which a candidate was accused of a crime, such as corruption, bribery, harassment, or pedophilia, in an effort to undermine the credibility and reputation of the targeted politician. Ten instances used the tactics of impersonation of media figures to mislead voters.

Eight instances misled the public about political events, such as the dates of rallies or the number of candidates on ballots. An additional eight were satirical and humorous political deepfakes. Five cases were pornography deepfakes, while four cases employed images of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and former President Jair Bolsonaro to deceive voters.

Forty-nine of the identified cases had been reported to Brazilian authorities, leading to investigations or legal actions.

Pornography deepfakes

Five female candidates were reported to be victims of deepfake deepfake pornography, in which AI was used to generate realistic-looking nude images. The incidents happened in the cities of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Bauru, and Taubaté, targeting the politicians Letícia Arsenio, Tabata Amaral, Marina Helena, Suéllen Rosim, and Loreny Caetano.

In one case , two deepfake images circulated on X portraying Tabata Amaral, the mayoral candidate for São Paulo. In one image, Tabata was presented as sticking out her tongue and wearing Playboy bunny ears. In the other, the congresswoman was presented in a swimsuit leaning suggestively on a sofa. The account @AQUELECARA posted the two images on September 7. The post received 114 comments, 138 shares, 2,200 likes and 612 bookmarks at the time of analysis.

Impersonation of media figures

The faces of prominent Brazilian journalists were extensively used in AI-manipulated videos to mislead voters. In ten instances, frames from broadcast news programs were edited using AI to either promote a candidate or damage their reputation.

In Igarapé do Meio, a city in the state of Maranhão, a deepfake video emerged on August 6 accusing the local government, including mayor Almeida Sousa, of financial fraud within the public education system. The video manipulated genuine footage broadcast from January 2024 by the TV program Fantástico. The original footage discussed financial crimes committed by public authorities in the cities of Turiaçu, São Bernardo, and São José de Ribamar, all located in Maranhão.

The video may have sought to damage the reputation of Mayor Sousa, who was supporting the candidacy of his wife, Solange Almeida.

Another instance emerged in Fortaleza, the capital of Ceará, involving mayoral candidate Evandro Leitão. A manipulated video falsely connected local politicians from Ceará to the largest criminal organization in Brazil, known as Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), using footage from the TV program Domingo Espetacular.

In Itapecuru Mirim, in Maranhão, and João Pessoa, the capital of Paraíba, candidates Ricardo Lages and Eliza Virginia posted deepfake videos on their social media accounts. These videos promoted the candidates by impersonating journalist William Bonner, the anchorman of Jornal Nacional, the most-watched Brazilian news program.

“Dr. Ricardo’s staff campaign has just announced that they will soon bring some great news that will be crucial for the election in Itapecuru,” said the deepfake anchor in a video posted by mayoral candidate Lages on his Instagram account.

The version shared by Eliza Virgina depicted Bonner claiming that she was “the best candidate for councilor for 2024”. It was posted on WhatsApp.

Political events

Another tactic identified by the DFRLab was the use of deepfakes to mislead voters about political events or the election more broadly. In eight instances, alleged deepfakes sought to cause confusion over ballots, voting locations and the like.

In Monsenhor Gil, a city located in the state of Piauí, an Instagram profile posted a deepfake video in which mayoral candidate Evandro Abreu appeared to be misleading voters on how to fill out ballots. The account was suspended in the first round of the election for publishing disinformation.

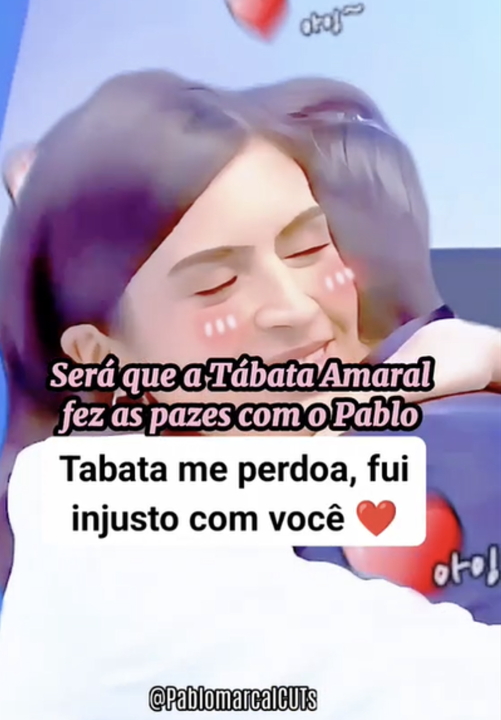

On September 25, a user shared an altered video in a public WhatsApp group featuring São Paulo mayoral candidate Tabata Amaral, in which she appeared to hug her political opponent, Pablo Marçal, during a debate. The video included the subtitles “Tabata, forgive me, I was unfair to you” and “Will Tabata forgive Marçal?” The video intended to misrepresent Marçal by depicting him admitting to committing personal offences against Amaral. At the end of the video, it falsely depicted the two candidates hugging, surrounded by red heart emojis and the phrase “Love you.”

Appropriation of images of Brazilian politicians

The political reputations of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and former President Jair Bolsonaro were used to either support or undermine candidates’ campaigns. Four identified deepfakes depicted Lula and Bolsonaro in manipulated audio and video clips.

In August, a TikTok video portrayed Bolsonaro urging his supporters to vote for candidate Pablo Marçal in São Paulo. “Despite past differences and discussions, I want to express my support for Pablo Marçal,” AI-generated Bolsonaro said in the video. “I ask all my friends and supporters to also support Pablo Marçal.”

The video includes a watermark for the TikTiok account @capitao.jairbolsonaro, suggesting this profile may have originally published the video. Although the account handle includes the former president’s name, it is not an official account.

Bolsonaro and Marçal engaged in a series of public disputes during the elections. Marçal sought the former president’s official support in the São Paulo mayoral race, but Bolsonaro supported another candidate, Ricardo Nunes.

Elsewhere, in the city of Mirassol, located in the state of São Paulo, a deepfake video circulated on public WhatsApp groups depicting candidates Junior Ricci and Valéria Volpe as supporters of the Workers’ Party (PT), which is affiliated with Lula. However, the two candidates belong to a different political party. The altered video featured a static image of the candidates and an invitation to a political event on August 4. It also featured a falsified audio clip of Lula allegedly saying, “Attention! Leftists of Mirassol, come to the party convention.”

Humorous deepfakes

The DRLab identified eight examples of satirical and humorous political deepfakes. While this format does not intend to mislead, in certain contexts it has the potential to distort public perception of events.

Humor was used to either undermine or promote candidates’ reputations. For example, Bruno Reis, the mayoral candidate for Salvador in Bahia, created and uploaded two promotional deepfake videos in September on his Instagram account depicting him dancing to his campaign jingles.

In another example, Brian Masçon, a councilor candidate in Baependi, a city located in Minas Gerais, posted a deepfake video on his Facebook account. The video featured a popular meme in Brazil in which a girl complains about a concert. The video replaced the girl’s face with Masçon’s and added a voiceover in which he said, “In this election, Brian can’t be left out. I work every day until 3 AM. What kind of Baependi is this?”

The same meme was applied in another deepfake targeting mayoral candidate Thiago Silva in Rondonópolis, a city in Mato Grosso. The politician claimed that the video was edited by his opponents and shared on WhatsApp to damage his reputation; he added that he had reported the incident to electoral authorities.

Credibility undermined by misconduct

The most common form of deepfakes we observed involved the publication of allegations of misconduct to undermine the credibility of a candidate. We identified twenty-seven cases in which candidates were accused of crimes, offences, or immoral behavior by deepfake content, often framed as leaked media.

In Ribeirão Pires, São Paulo, mayoral candidate Gabriel Roncon reported being a victim of a video on WhatsApp which contained AI-generated audio purporting to be his voice. In the audio, he appears to admit to having tampered with the results of an electoral poll.

In Vitória do Xingu, Pará, mayor Márcio Viana reported to local authorities that he was a victim of a video deepfake posted in WhatsApp groups. The video depicted a man being intimate with a teenager. Alongside the video, text claimed the man in the footage was the mayor.

In multiple cases, candidates who were victims of deepfake content defended themselves publicly via their social media accounts. These include six cases in which candidates sponsored ads on Meta platforms to amplify the fact that that they had been targeted.

In certain instances, candidates attempted to refute or cast doubt on all instances of leaked content, even those that appeared credible. This highlights how the spread of manipulated media can simultaneously undermine the credibility of authentic content, thus creating a situation known as the liar’s dividend. For instance, in Fortaleza, mayoral candidate André Fernandes used his social media accounts to claim that he was targeted by an alleged deepfake audio circulating on WhatsApp impersonating his voice. He accused his opponent, Evandro Leitão, of creating the deepfake, in which Fernandes allegedly discussed distributing money to pastors and community leaders to buy votes, after falling behind in the polls for the municipal election runoff. At the time of writing, the candidate had not yet provided evidence that the audio was falsified. Additionally, the fact-checking organization Projeto Comprova submitted the audio for analysis by experts and tools designed to identify deepfakes, but the results were inconclusive.

In Palmas, the capital of Tocantins, another case involving an alleged deepfake also remains inconclusive. On September 23, mayoral candidate Professor Júnior Geo broadcast on television an audio clip purported to be of his opponent, Janad Vacari. In the audio, the voice attributed to Janad aggressively addressed an employee, referring to the person as an “idiot.” This recording circulated widely on WhatsApp groups during the electoral campaign, but Janad disputed its authenticity, claiming it was an audio deepfake. The case is currently under investigation.

Alleged deepfakes that didn’t involve AI

As the research focused on user discussions and news reports referring to instances of deepfakes during the electoral calendar, it led to several instances in which content was erroneously purported to be AI-generated when it had simply been edited without AI tools.

The DFRLab observed that these inaccurate descriptions persisted not only among candidates but also among judges and authorities who were examining potential violations of the electoral regulation. For example, in Gravataí, a city in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, an electoral judge ordered candidate for councilor Paulo Silveira to remove an alleged deepfake from his Instagram account. This content was said to be targeting mayoral candidate Luiz Zaffalon and his running mate Levi Melo. The legal action was initiated by the two candidates who claimed that Silveira posted an altered image on his Instagram account portraying them as clowns. The photo was accompanied by a critique of the local public health service.

In the legal case, Zaffalon and Melo claimed that the content in question was a “deepfake” because it featured the candidates’ heads on the bodies of different characters. They also requested the revocation of the councilor’s electoral registration.

In a preliminary decision, electoral judge Valéria Eugênia Neves Wilhelm accepted their claim and ordered the immediate removal of the content. However, in a followup decision, judge Régis Pedrosa Barros rejected the classification of the image as a deepfake, instead recognizing it as an instance of basic image editing. “Although the image included with the message is in very poor taste and could even lead to claims for moral damages in civil court, it is not a deepfake, but rather a crude montage,” he said. The cases analyzed by the DFRLab reveal confusion stemming not only from a misunderstanding of the definition of deepfakes but also from a lack of clarity in electoral regulations regarding the classification of synthetic content. Additionally, the limited access to tools to verify the authenticity of deepfake media allowed this confusion to persist within in the information environment.

Cite this case study:

Beatriz Farrugia, “Brazil’s electoral deepfake law tested as AI-generated content targeted local elections,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), November 26, 2024,