Assad’s silent network: Syrian influence operations in Latin America

Assad regime effectively exploited the region’s existing disinformation networks, inserting narratives into popular sociopolitical causes

Assad’s silent network: Syrian influence operations in Latin America

Banner: People carry images of late Cuban President Fidel Castro and then-Syrian President Bashar al-Assad during the May Day rally in Havana, May 1, 2019. (Source: Reuters/Alexandre Meneghini)

Bashar al-Assad’s flight to Russia on December 9, 2024, marked the end of Syria’s fifty-year authoritarian dynasty that cost the lives of approximately half a million people. While this event symbolized a domestic turning point, it also disrupted the regime’s quiet but persistent influence operations in Latin America. Assad’s strategy relied on disinformation campaigns and tactical alliances, enabling the regime to build subtle but important impact.

Compared to China, Cuba, Iran, Russia, or Venezuela, Assad’s operations in Latin America were smaller in scope. Yet, his regime effectively exploited the region’s existing disinformation networks, aligning with popular social and political causes to insert its narratives. This allowed Assad to maintain a niche foothold in the disinformation space.

By the regime’s fall, it had developed a network that included a state-backed media platform, diaspora communities, and alliances with sympathetic political actors—often coordinated through Syrian embassies. These tools helped Assad bolster his legitimacy abroad, deflect criticism, and sustain his regime’s global influence. This investigation focuses specifically on the disinformation tactics and campaigns aimed at influencing the Latin American public.

Media presence

Bashar al-Assad’s regime utilized its alliances with authoritarian regimes in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela to penetrate Latin America’s disinformation landscape. The pre-existing influence networks and media infrastructure in these countries acted as conduits for the Syrian regime’s propaganda.

At the center of the media operations was the official state-controlled news agency SANA, which produced daily content in Spanish alongside other languages. The output was accessible through its website. SANA used a multichannel approach actively disseminating propaganda across various social media platforms, including Facebook, YouTube, Telegram and Twitter.

SANA resorted to cooperation agreements with Latin American media in the service of authoritarian regimes to reinforce its disinformation strategy, partnering with Cuba’s Prensa Latina and Venezuela’s TeleSur. The objective of these agreements was to increase the circulation of content and to challenge what they described as “disinformation produced by major media monopolies.”

From this collaboration came the documentary “Siria Resiste” (“Syria Resists”) in 2016, which accused Western media of misrepresenting the Syrian civil war. The film’s director, Miguel Fernández Martínez, then a correspondent for Prensa Latina, currently collaborates with Sputnik, a Russian disinformation platform.

On October 30, 2017, Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that Prensa Latina Vice President Héctor Miranda visited Damascus to renew its partnership with SANA. The meeting included Prensa Latina correspondent Oscar Bravo and Pablo Ginarte, the Second Secretary of Cuba’s Embassy in Syria.

The agreement enabled Prensa Latina to amplify Syrian regime messaging by producing favorable content and translating SANA articles into Spanish, hosted on a dedicated platform. Cuba’s disinformation ecosystem, through outlets like CubaDebate, CubaSi, Granma, and Nodal, further disseminated these narratives to local and global audiences.

Simultaneously, SANA expanded its Arabic and Spanish output, producing articles and videos that provided favorable coverage of the Cuban regime. This content emphasized key events, commemorative dates, and official statements, underlining bilateral ties and mutual friendship.

A similar strategy was extended to the Venezuelan regime. Records indicate that as early as 2006, Hugo Chávez and Bashar al-Assad signed memorandums to strengthen cooperation in media and communication. TeleSur not only crafted pro-Syrian regime narratives for its audiences but also broadcast direct messages from Assad himself through interviews produced in 2013 and 2017, with the possibility of additional instances. In return, SANA produced content commemorating Hugo Chávez and promoting Nicolás Maduro’s leadership.

The biased coverage of Syria by Prensa Latina, SANA, and TeleSur functioned as a mechanism for news whitewashing. Local media, often unaware of the broader disinformation dynamics but eager for timely reporting on developments, unintentionally republished content from these outlets. This pattern appeared in media such as Brasil de Fato in Brazil, Diario Co Latino in El Salvador, and BoliviaTV and El País Tarijain Bolivia.

On June 10, 2024, SANA and Prensa Latina covered an event held at the Cuban Embassy, organized by Ambassador Luis Mariano Fernández Rodríguez. During the gathering, Prensa Latina journalist Fady Marouf and TeleSur correspondent Hisham Wannous were recognized for their “role in transmitting the truth and defending just causes hidden by mainstream media” about Syria. The meeting highlighted the collaborative relationship between the three media organizations.

Fady Marouf, who also served as head of SANA’s Spanish-language news section, had been decorated two years earlier by Ricardo Ronquillo, President of Cuba’s Union of Journalists of Cuba (Unión de Periodistas de Cuba, or UPEC by its acronym in Spanish) with the “Dignity Award,” for his “commitment to objective journalism in defense of the truth.”

Moreover, the Spanish-language office of SANA included journalists like Ghinwa Maia, based in Damascus, and Arowh Mahmoud, stationed in Havana. Their work focused on producing content that projected the image of a stable and functional Syrian regime, and the Assad family. The conflict with rebels was consistently framed as a product of external powers. Additionally, the office frequently produced stories promoting Syria’s bilateral relations with strategic allies like China and Russia.

Alongside its coordinated disinformation efforts with regional authoritarian allies, the Syrian regime’s narratives were spread through international platforms linked to external actors. Channels like Sputnik, Russia Today, Xinhua, and HispanTV, which operate in Spanish and Portuguese, amplified Assad’s messaging, enhancing its reach and embedding it within a pro-regime narrative in Latin America.

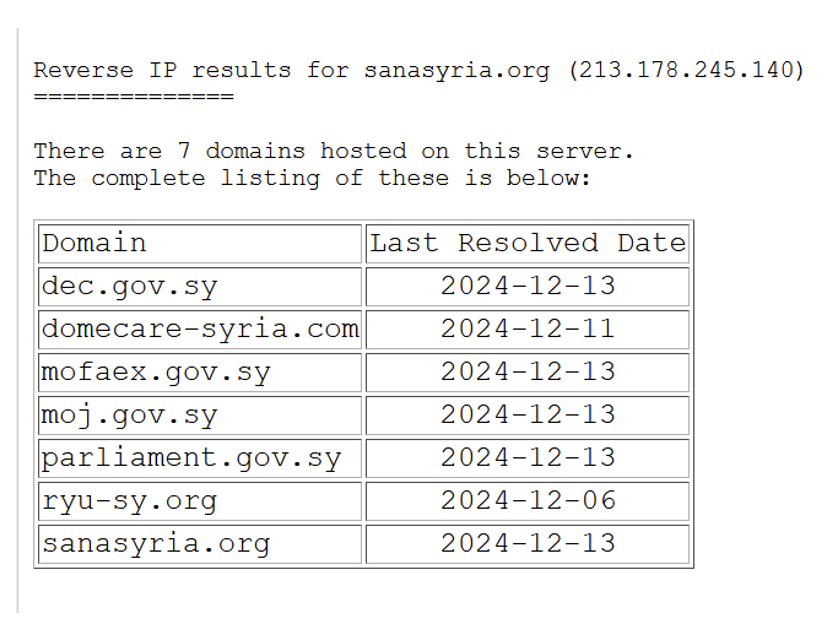

The investigation also identified sanasyria.org/es, a mirrored version of the official SANA news agency site. This duplication appeared to be a strategy to circumvent firewalls or content restrictions. While such blocks were improbable in Latin America, the site guaranteed continuous dissemination of Syrian regime narratives.

Reverse search techniques on the domain sanasyria.org revealed that it shares the same hosting server as official Syrian government websites, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Justice, and the Syrian Parliament. This connection provides strong evidence of the Assad regime’s direct involvement in managing this disinformation platform targeting Latin American audiences.

SANA also adopted established disinformation tactics to build credibility with Latin American audiences. It collaborated with media outlets like Spain’s La Comuna magazine and featured Spanish-speaking academicians such as Pablo Sapag, who framed the Assad regime as a reaction to geopolitical divisions and Western disinformation. The platform also exploited the visibility of well-known Latin American leftist figures, including Aleida Guevara, Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s daughter, to enhance the reach and acceptance of its messaging.

An analysis revealed shared and coordinated narratives emerging from the Syrian regime and the broader disinformation ecosystem. These narratives emphasized anti-imperialism, anti-American and anti-Israel rhetoric, and a strong focus on national sovereignty. They frequently condemned sanctions and external pressures, advocating instead for an alternative political and economic order. This alignment also emphasized solidarity within the Global South as a means to challenge perceived capitalist and hegemonic dominance.

Disinformation on X

SANA’s Spanish-language presence on X (formerly Twitter) began in December 2019, gaining a following of about 49,000 users. An analysis of activity between January 2022 and December 17, 2024, shows the publication of 32,845 tweets. During this period, the account accumulated 1.3 million likes and 867,525 retweets, expanding its visibility. For this investigation, the tweets were categorized by country and narrative focus, with 95% successfully coded, while 1,586 tweets remained uncategorized.

Since 2022, SANA’s output directed at Latin American audiences has predominantly focused on six key actors: Syria, Russia, Israel, Ukraine, Palestine, and the United States. Intriguingly, “The West” — often associated with NATO — ranked as the eighth most significant theme, portrayed as a destabilizing global influence.

Alongside its focus on legitimizing the Assad regime, Syrian disinformation operations dedicated 37.1% of their output to promoting allied authoritarian regimes, such as Algeria, Belarus, China, Cuba, Iran, Nicaragua, North Korea, Russia, and Venezuela. While propaganda coordination with Cuba exists, Russia dominated the content share with 76.91%, followed by Iran at 10.11% and China at 9.77%. In comparison, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela accounted for only 3.39%, 0.45%, and 2.15%, respectively.

Graph: Allies Autocratic Regime Mentions

As expected, SANA functioned as an instrument to promote and legitimize Bashar al-Assad’s regime to external audiences. The dominant narrative portrayed the government as rebuilding Syria, fostering national reconciliation, and restoring normalcy. Al-Assad, along with his wife and ministers, was consistently depicted as leading these efforts and delivering motivational messages. The messaging also emphasized how government and civil stability were threatened by the activities of “terrorists” still operating in the country.

The conflict between Israel and Palestine, as well as Lebanon, generated the most audience engagement for SANA. However, the coverage was extremely biased, consistently depicting Palestinians as victims of Israeli aggression. For instance, during the October 7, 2023, attacks, in which Hamas entered Israel, killing, kidnapping, and committing acts of sexual violence, SANA characterized the events as acts of Palestinian “resistance.” Amid the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, SANA capitalized on the regional solidarity in Latin America to emphasize the Syrian regime’s backing of the Palestinian cause. By aligning itself with an issue that resonates deeply with specific sectors, the regime sought to promote its image as a positive actor.

Notably, this investigation highlights SANA’s role as a mirror platform for disseminating Russian propaganda across Latin America. In a region often targeted by disinformation campaigns from authoritarian actors, SANA integrated and amplified Russian narratives. This included supporting disinformation regarding the invasion of Ukraine and promoting Russia as a victim of sanctions imposed by Europe, NATO, and the United States.

Other prevalent discourses consistently characterized the United States as a destabilizing power. The narratives accused it of invading sovereign states, imposing sanctions, supporting Israel’s operations, killing civilians, and undermining Syria’s security through the financing of terrorist groups.

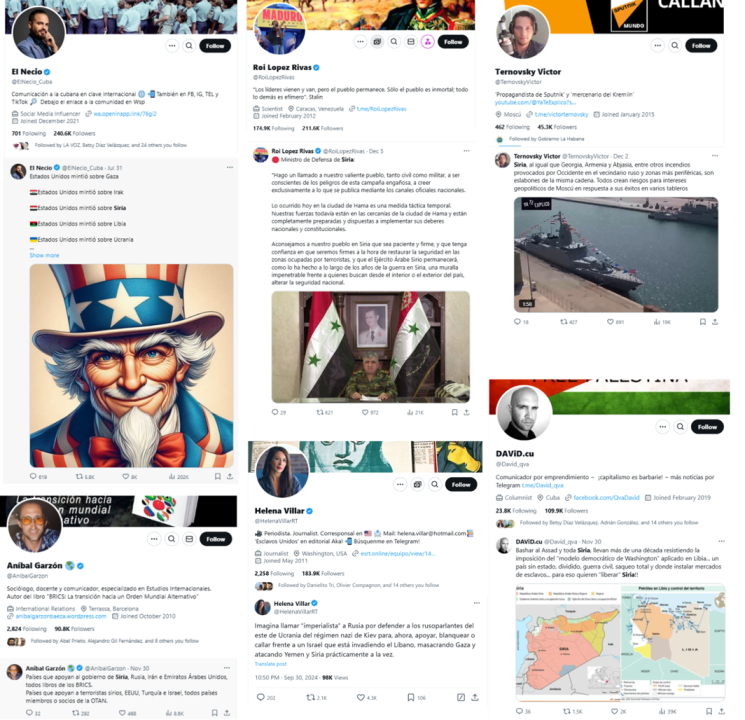

Another aspect of the dissemination of narratives relied heavily on prominent disinformation actors linked to authoritarian regimes across social media. Bots, a critical element of the digital propaganda ecosystem, played a central role in amplifying this content. Their messaging consistently underscored Western culpability in the Syrian crisis, redirecting attention away from the regime’s actions.

Conclusion

The Syrian disinformation campaigns aimed at Spanish-speaking audiences, bolstered by regional influence networks, raise important points. Firstly, it illustrates how even small authoritarian states with limited financial resources prioritize building propaganda frameworks to spread disinformation internationally. Secondly, it highlights how these regimes collaborate with each other to amplify narratives, thereby distorting reality and diverting attention from issues that undermine their legitimacy. For instance, Syrian propaganda, tailored for Spanish-speaking audiences, placed significant emphasis on promoting Russian, Iranian, and Chinese narratives.

Thirdly, the findings show that the campaigns sought to position Syria as a supporter of popular causes in the region, fostering legitimacy and support among target audiences. Bashar al-Assad’s regime also benefited from preexisting regional disinformation ecosystems created by other authoritarian states, alongside its control over other international media outlets such as Al-Mayadeen. Finally, the passivity and failure of Latin American governments to recognize the threat posed by foreign interference and disinformation allowed the Syrian regime to maintain unhindered operations in the region.

Despite its efforts, the pro-Syrian regime propaganda never reached the scope of that of other actors such as Cuba, Russia and Venezuela. It was marginalized and confined to the most radical supporters of these regimes or specific organizations within the Arab diaspora. As a result, Bashar al-Assad’s fall was widely welcomed by the media, political figures, and the public at large. In contrast, the cooperative relationship between the Cuban and Syrian dictatorships led to other repercussions. Following the arrival of rebels in Damascus, the Cuban embassy was targeted, forcing its personnel to flee to Lebanon.

Michel Navarro is a researcher and PhD candidate at Corvinus University of Budapest, where he focuses on lobbying activities, influence and information operations, and foreign interference conducted by authoritarian states targeting democratic societies. He is an alumnus of the DFRLab Digital Sherlocks program. Additionally, he has served as a lecturer in geopolitics at Metropolitan University of Budapest and collaborated with Global Voices.

Cite this case study:

Michel Navarro, “Assad’s silent network: Syrian influence operations in Latin America,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), February 5, 2025, https://dfrlab.org/2025/02/05/assad-syria-latin-america.