Protests Go Viral in Venezuela

Venezuelan protestors gather amid internet blocking attempts by the Maduro regime

Protests Go Viral in Venezuela

BANNER: (Source: @DFRLab)

Protests held around Venezuela on Wednesday, January 23, 2019, garnered widespread coverage around the world. In monitoring the protests, @DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center found reports of internet blockages, identified viral hashtag use, and were able to determine rough estimates for the crowd size of the main rallies on both sides in Caracas.

The January 23 protests happened amid a crisis that has engulfed the country for the last five years. Millions of people have fled the country, where food and medicine shortages are rife and inflation is currently projected to hit 10 million percent in 2019. In 2018, Nicolás Maduro won the Venezuelan presidential election, though many nations in the international community deemed the results fraudulent and with some countries referring to Maduro as a “dictator.”

January 23 is a historic day of protest in Venezuela dating back to 1958 when the country underwent a coup d’état to overthrow its dictator, Marcos Pérez Jiménez. This year was marked by massive protests in the streets and online, as well as dozens of violent incidents that have left at least 26 people dead, according to local sources.

In the midst of the protests, opposition leader Juan Guaidó, the National Assembly President, took an oath to be Interim President of Venezuela. The United States, Canada, Brazil, and most Latin American countries quickly recognized Guaidó as the acting head of state and government.

As the protests played out in streets across the country, the information environment online experienced similar activity, including disruption and virality

Internet Blockages

Throughout January 23, 2019, one of the state’s internet service providers (ISPs) likely throttled, which means to speed up or slow down the internet in a given area, and blocked parts of the internet amid the face-off between regime and opposition supporters.

January 23, however, was not the first time there have been reports of internet blockages in Venezuela. In June 2018, news emerged that some users were having problems accessing El Nacional, one of the main newspapers in the country. Also in June, TOR Network, a tool used to preserve privacy and browse anonymously, was also blocked by Cantv, a state-owned ISP that leads the home connection market in the country. A later study conducted by Venezuela’s Press and Society Institute found evidence of intermittent blockage of independent news websites Armando.info and El Pitazo, both on state and private internet operators, in August 2018.

Two days after Nicolás Maduro took his oath for a second term as president on January 10, Venezuelan internet users reported being unable to connect to Wikipedia in all languages. Venezuela Sin Filtro, a local non-profit dedicated to monitoring and countering internet restrictions in the country, reported that a Wikipedia blockage occurred from the morning of January 12 until January 18.

According to findings by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), the blockage started after several articles on Wikipedia were altered to refer to Juan Guaidó as President of Venezuela. OONI confirmed the existence of the block by Cantv. On January 21, Venezuela Inteligente reported a similar block, this time affecting Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

In this context, activists expected new blockages on January 23. Indeed, new connection difficulties were noticed by many sources, including Netblocks and Venezuela Sin Filtro, which stopped short of calling the situation a disruption.

Despite these constraints, social media activity around the January 23 political events went viral. Even with these reported restrictions in place, both pro- and anti-Maduro social media users shared hashtags and images of the protests, reinterpreting their content to suit each side’s agendas.

Later, in the afternoon, Maduro gave his own speech in which he stated that “the international media is censoring the Venezuelan people.” In doing so, he claimed that, while the opposition protests got wide coverage on news and social media that day, those supporting the regime did not. @DFRLab analysis, however, shows that the disproportionate coverage was representative of the differing size and spread of the two sides’ protests, with the opposition demonstration drawing a much larger crowd than the pro-Maduro marches and taking place in more parts of the country.

Crowd-size Estimates

Both pro- and anti-Maduro demonstrations took place on January 23, though they assembled in different parts of Caracas, Venezuela’s capital. Most mainstream media outlets, such as The Guardian, could only provide a very rough estimate, usually stating the crowd size to have been in the tens of thousands.

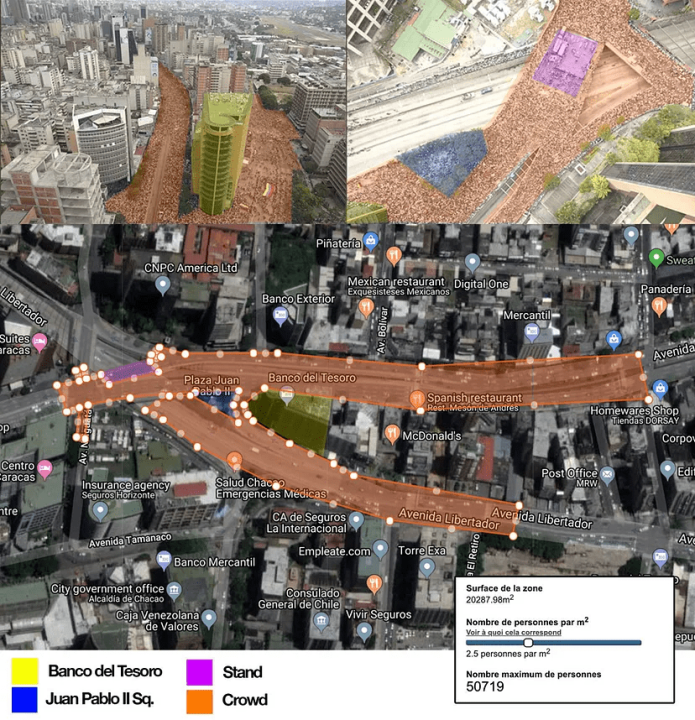

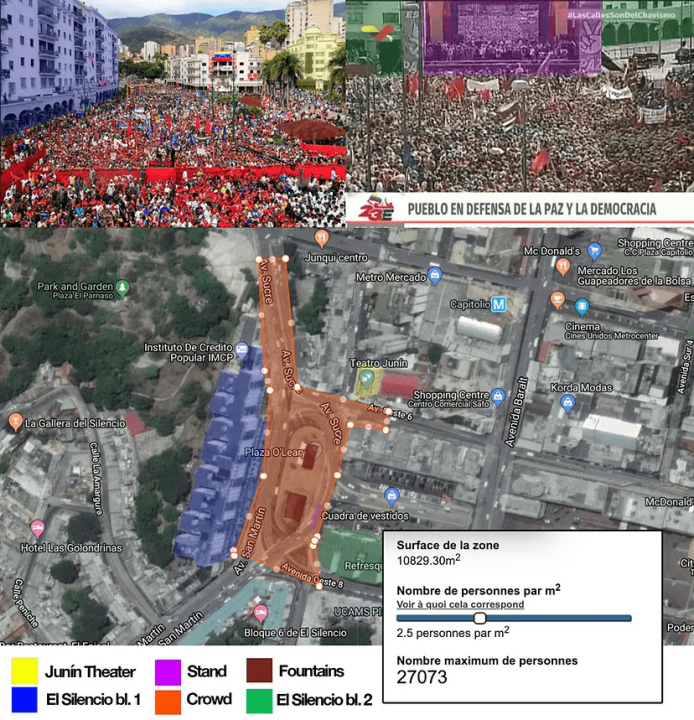

In performing its analysis, @DFRLab looked at the main gathering locations for each march: the pro-Maduro march gathered in the O’Leary Square (near the Parliament and Miraflores Palace, the Venezuelan presidential house) while the anti-Maduro protest assembled in Juan Pablo II (John Paul II) Square in the financial district of Chacao.

To compare the attendance at each march, @DFRLab chose photographs from social media that captured a wide perspective and, using the tool MapChecking, determined a crowd-size estimate. To ensure the most accurate estimates, we selected images that were published when each gathering seemed to be at peak attendance and that were consistent with other photographic evidence posted around the same time.

While the actual crowd density is impossible to determine, @DFRLab assumed a crowd density of 2.5 people per square meter for the photos being analyzed based off of the relative density in the photos.

Per social media reports, the Chacao (anti-Maduro) protest assembled well before 12:00 p.m. Venezuela time, when Guaidó’s speech was scheduled. Guaidó actually started speaking at 1:35 p.m. @DFRLab analysis of photos posted by Twitter account @MariaAlesiaSosa at 11:36 a.m., two hours before Guaidó’s speech, estimates that Juan Pablo II Square held an approximate crowd of over 50,000 people at that time. The pictures are consistent with dozens of other images and videos posted on Twitter between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. the same day.

Maduro, on the other hand, was originally scheduled to speak at 1:00 p.m., though he also did not speak on schedule. Diosdado Cabello, President of the Venezuelan Constitutional Assembly and one of Maduro’s strongest allies, gave a speech at the pro-Maduro rally, starting at 3:00 p.m. Cabello announced that Maduro would offer his speech from the balcony of nearby Miraflores Palace, where he finally took the stage around 4:00 p.m.

Cabello’s crowd in O’Leary Square, which was presumably bigger than Maduro’s since the regime leader was initially expected to make his appearance there, was roughly 27,000 people strong. The analysis was made based on a video of Cabello’s speech on YouTube and a photograph taken from the stand, posted by the account @Maduro_en at 4:39 p.m.

Hashtag Campaigns

A common feature of the Venezuelan social media sphere is a daily, regime-led hashtag campaign. As a means of counter-programming the official hashtags, Maduro’s opposition has also started using similarly political hashtags to drive the narrative online.

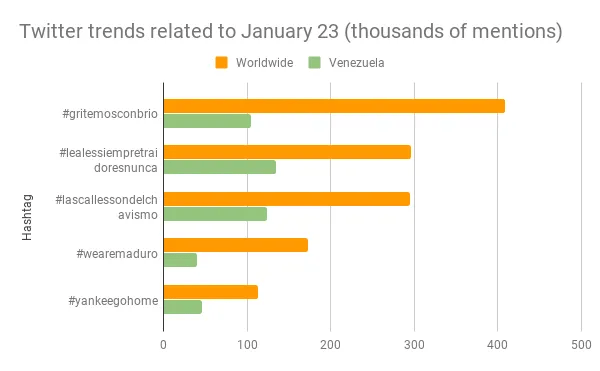

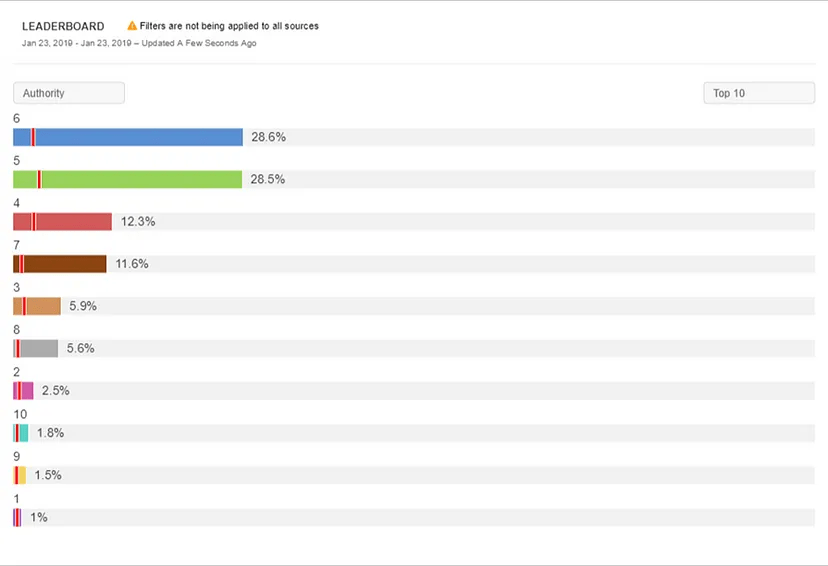

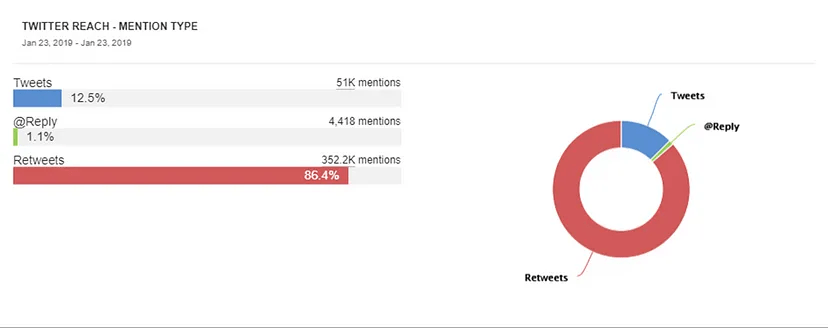

To analyze Twitter trends in and on Venezuela on January 23, @DFRLab aggregated the most popular hashtags. On Twitter, the most popular hashtag in the country supported Maduro, while a pro-Guaidó hashtag was the most prevalent globally. Among the 10 most mentioned hashtags in the country, five were clearly connected to one side or the other (with four linked to Maduro and one to Guaidó), and the remaining five related to the protests were used by both Maduro’s and Guaidó’s supporters.

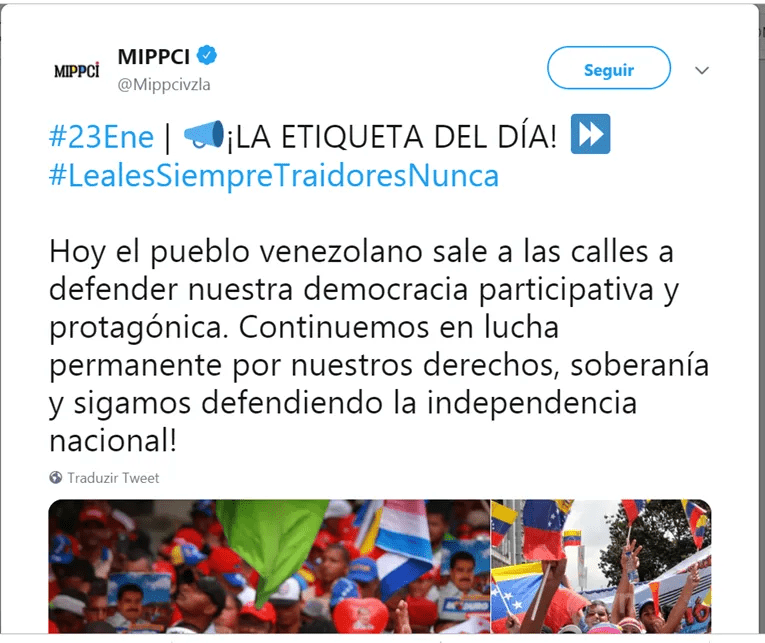

In Venezuela, the most popular hashtag was #lealessiempretraidoresnunca (translated from Spanish, “Always loyal, never traitors”), which was initially pushed by the Twitter account of the Venezuelan Ministry of Communication and Information.

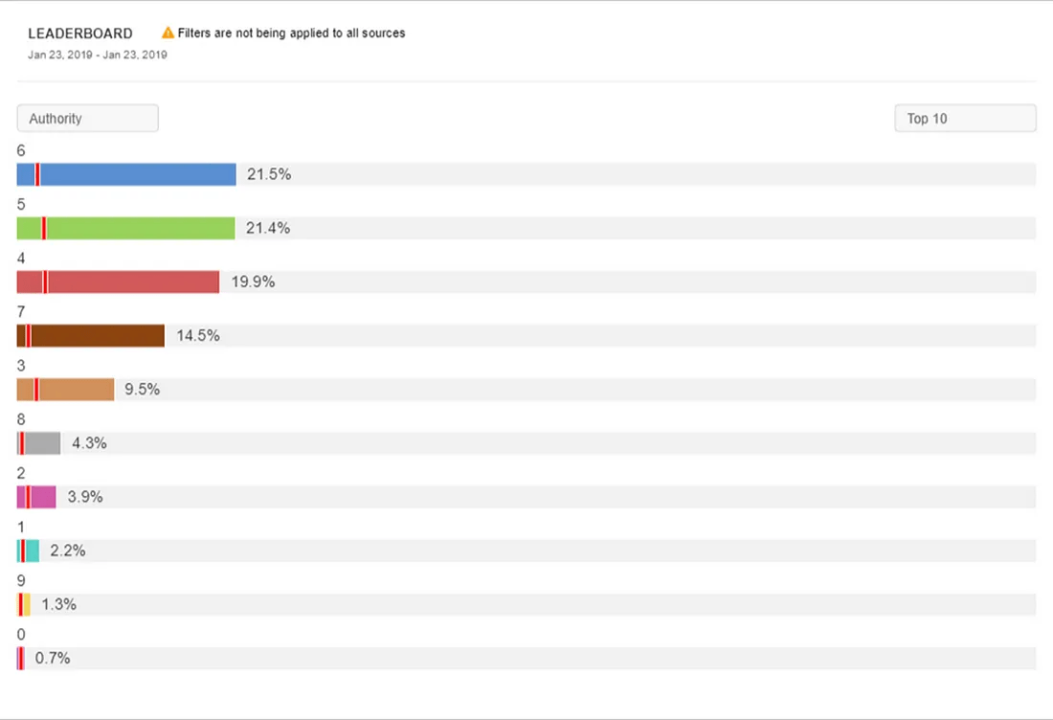

While there have been reports in the past about the Venezuelan government using bots to amplify its content online, a preliminary analysis by @DFRLab did not find clear evidence of automated amplification of hashtags trending around the protests. The vast majority of the accounts that used it (89.9 percent) had an authority score above 4, which is not considered suspicious. Authority scores are based on an account’s activity and influence. When the average authority scores of all accounts used in a hashtag campaign falls between 1 and 3, the activity indicates the presence of bots, which typically have authority scores in that range. On average, accounts with an authority score of zero to three make up about 21.4 percent of all Twitter users.

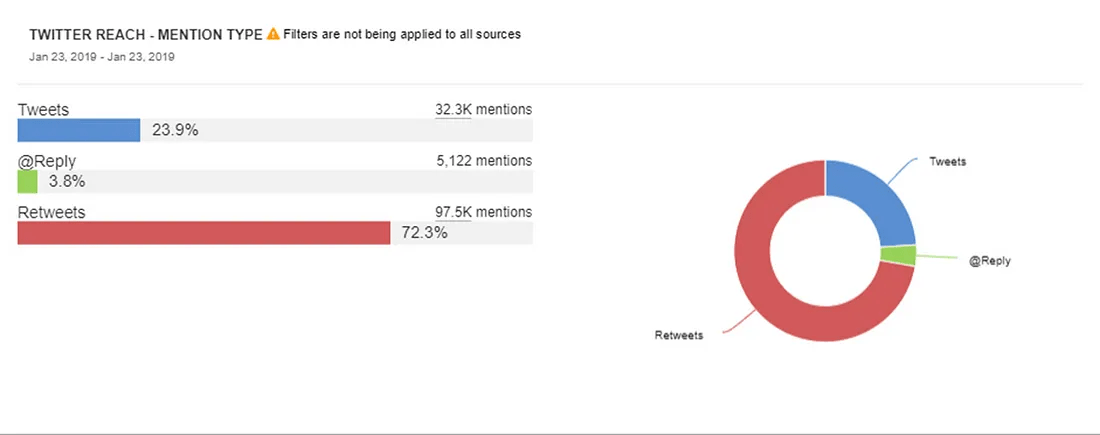

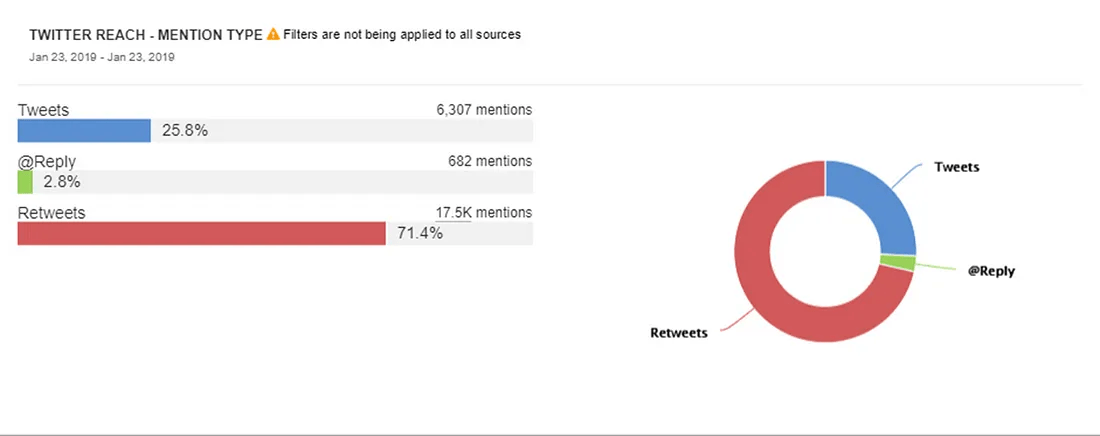

The scan also shows that most mentions to the hashtag were retweets rather than original posts. The percentage of retweets (72.3 percent) was higher for the #lealessiempretraidoresnunca hashtag than for the hashtag #23ene (#23Jan), which was used both by the opposition and by Maduro supporters. A large proportion of retweets using a hashtag is one indicator of automated accounts, as they use retweets to amplify their message. More research is needed, however, to identify whether there are signs of bot-like behavior on the amplification of the regime-pushed hashtag.

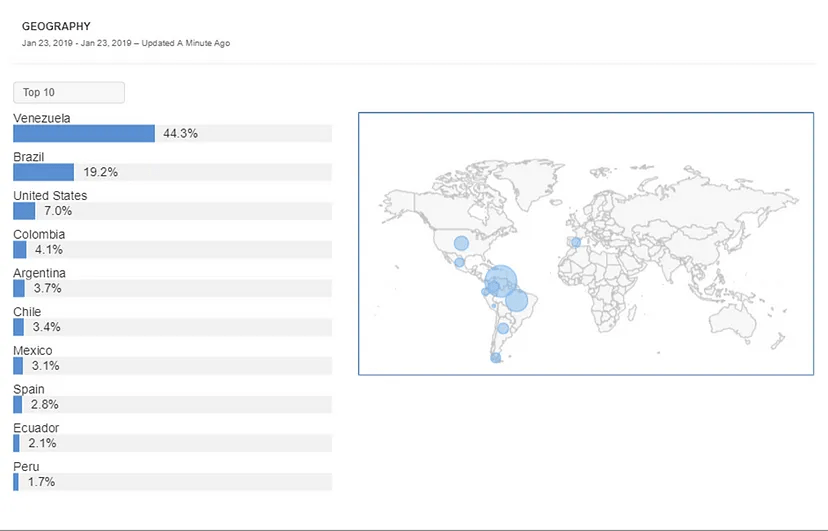

The most mentioned hashtag about the events worldwide was #gritemosconbrio, which was posted by Guaidó, amplified by his supporters, and yielded 408,800 mentions. The sum of the hashtag mentions in support of Maduro in the top 10 outperformed #gritemosconbrio, the only exclusively pro-Guaidó hashtag to make the top 10. Some posts, however, used multiple hashtags, thus this total number does not represent the most posts, only the most mentions.

The pro-Guaidó hashtag was particularly inflated by users in Brazil and the United States, two of the first countries to recognize Guaidó as the legitimate President of Venezuela. In Brazil, where the hashtag performed particularly well, the threat of “Venezuelization” was used by far-right then-candidate, now-President Jair Bolsonaro during his 2018 electoral campaign. Again, a preliminary analysis found no evidence of inauthentic amplification of the hashtag.

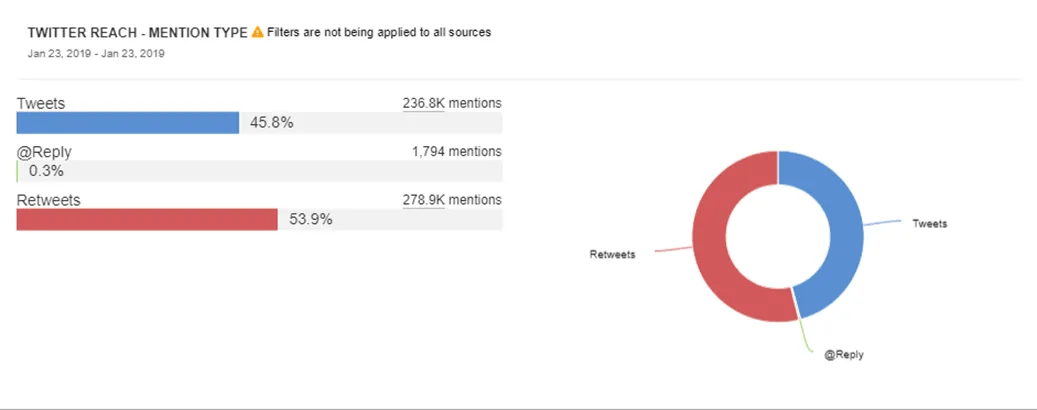

The machine scan also shows that the number of retweets of the pro-Guaidó hashtag was bigger than the one of the hashtag #23ene (53.9 percent retweets).

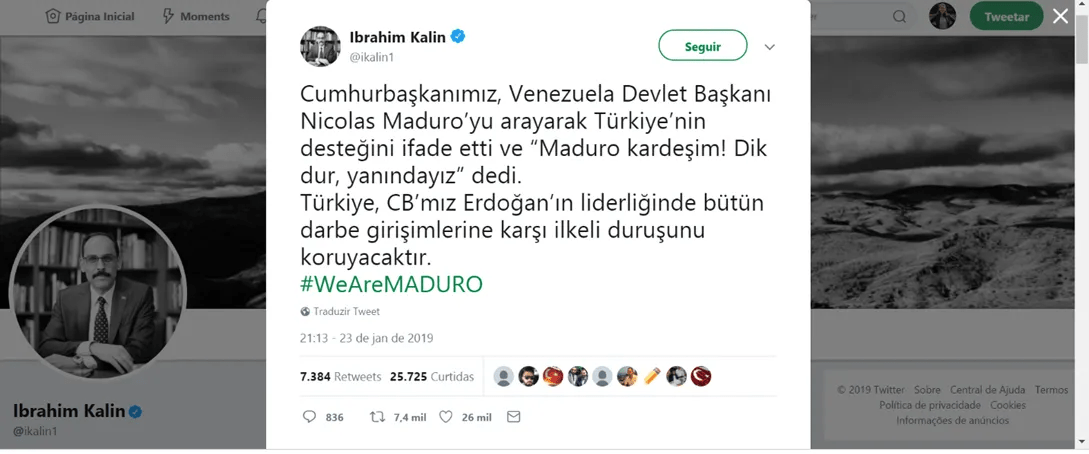

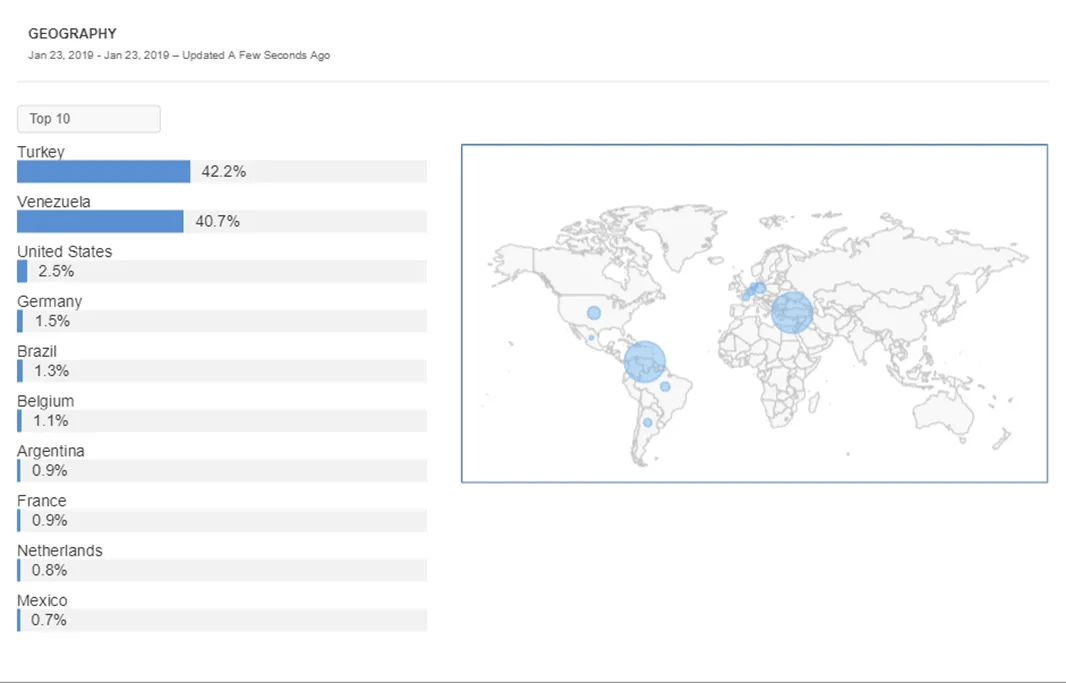

A separate, unexpected trend centered around the hashtag #WeAreMaduro, which started in Turkey and received, by a narrow margin, more mentions in the country than in Venezuela. Turkey was one of the countries that offered support to Nicolás Maduro, with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan considering Guaidó’s declaration a coup.

The most popular post using the hashtag was made by Ibrahim Kalin, the presidential spokesperson. It was retweeted 7,384 times as of January 25. He wrote “Turkey stands against any coup attempts.”

A preliminary analysis of the authority scores for the Turkish accounts using the hashtag did not show that they were coming from low authority accounts, indicating that accounts that exhibit bot-like behavior did not factor heavily into the spread of this hashtag. In a similar fashion to the hashtags analyzed previously, #weareMaduro had a higher percentage of retweets than the “neutral” hashtag #23ene.

Conclusion

Despite connection difficulties and suspected blockages, the Venezuelan internet was alive with activity during the January 23 protests. People at the protests, both those in favor of and against the Maduro regime, actively published photos and videos to social media, allowing for multiple perspectives of the events. Maduro nevertheless complained that social media coverage was one-sided against him.

@DFRLab’s analysis on crowd-size reveals that the anti-Maduro gathering was significantly larger than the pro-regime rally, with approximately 50,000 attending the former and roughly 27,000 at the latter.

Trending hashtags on Twitter regarding the events in Venezuela that day had mixed popularity, locally and globally: a pro-Maduro hashtag yielded the most mentions in Venezuela, while a pro-opposition hashtag was the most used worldwide.

The consequences of the protests on January 23 are still being felt and will continue to be for many days to come.

Jose Luis Peñarredonda is a Digital Forensic Research Assistant at the @DFRLab.

@DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center will continue to analyze the events of the day to provide further insight into what transpired.