#ElectionWatch: Beyond Russian Impact

What effect Russia’s U.S. operation had and how to respond

#ElectionWatch: Beyond Russian Impact

What effect Russia’s U.S. operation had and how to respond

Ever since Special Prosecutor Robert Mueller published his bombshell indictment of thirteen Russians for interfering in the 2016 U.S. election, debate has reignited over whether the meddling actually made a difference.

It is important to first answer this question, and then move beyond it, because until Americans can agree on what Russia did, they are unlikely to agree on how America should respond. With the midterm elections fast approaching, a rational response is vital.

Opinions on whether Russia’s operation made a difference themselves differ sharply. “The results of the 2016 election were not impacted or changed,” tweeted U.S. President Donald Trump, the weekend after the indictment.

General McMaster forgot to say that the results of the 2016 election were not impacted or changed by the Russians and that the only Collusion was between Russia and Crooked H, the DNC and the Dems. Remember the Dirty Dossier, Uranium, Speeches, Emails and the Podesta Company!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 18, 2018

“Thirteen people interfered in the US elections? Thirteen against multi-billion-dollar budget special agencies? Against intelligence and counterintelligence, against the newest technologies? Absurd? — Yes,” wrote Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zahkarova.

Russia’s actions “helped get Trump elected,” retorted Trump opponent Scott Dworkin, on Twitter as @funder.

Russia paid for Facebook ads promoting Jill Stein: ‘Trust me, it’s not a wasted vote’

It only helped Trump get “elected.” #TrumpColluded https://t.co/W6E3W5Lylq

— Scott Dworkin (@funder) February 18, 2018

Did Russia change or impact the results? Part of this question is beyond the reach of open source research. Judging whether Russia’s operation changed the election results could only be done by reading voters’ minds or accurate polling, and trying to establish which specific piece of information tipped them one way or the other.

We can, however, estimate whether the operations had an impact on voters and their votes, by analyzing how they affected the manuevers of the Trump and Hillary Clinton campaigns.

In the intensity of election season, any event which makes one candidate look bad, and the other look good, has the potential to change individuals’ voting intentions. The more events, the greater the potential.

Therefore, an operation which consistently makes one side look bad or unpopular, and makes the other side look good or popular, over a long period, is almost certain to have some impact on the vote tally. That impact may be marginal; but even a marginal change can, in a tight race, make a difference.

Did Russia’s influence operations behave in that way? The answer is an unequivocal “Yes.”

Starting on October 7, 2016, and every day until the election, Wikileaks released troves of emails hacked from Clinton campaign manager John Podesta by Russian hackers. The attribution of Russia to the hacks has been confirmed by the U.S. intelligence community, Dutch intelligence, and cyber analysts at ThreatConnect and CrowdStrike.

Those leaks put the Clinton campaign — already under pressure over Clinton’s private email server — at a competitive disadvantage. The mainstream media around the world ran articles on the Podesta leaks throughout the critical final month.

All that month, the Clinton team responded to the leaks, which reducing their ability to build any positive narrative or handle other problems, notably the negative narrative around the private server — a significant burden for any campaigning team in the countdown to voting day.

Were the leaks alone enough to tip the election to Trump? Probably not. Would Clinton’s campaign have been able to perform differently if the leaks had never happened? Certainly.

Much the same applies to the emails which Russians hacked from the Democratic National Committee and leaked before the Democratic National Convention.

The hacks provided a dark undercurrent to reporting as Clinton sealed the nomination. The behavior they exposed led to the resignation of DNC Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz — a setback for any campaign, less than four months from voting day.

Without the DNC leaks, both the DNC and the Clinton campaign would have been able to behave differently in the build-up to the election. That was not a decisive impact, but it was an impact in close election nonetheless.

Clinton’s disadvantages were Trump’s advantages. Both candidates had handicaps, but only Clinton’s campaign was further handicapped by two damaging sets of leaks provided from the Russia Federation. That gave the Trump team significant extra ammunition.

Trump himself mentioned Wikileaks or its leaks well over 100 times in the final month of campaign. These included at least 14 tweets mentioning Podesta or Wikileaks between October 7 and November 8, urging people to read the leaks.

“I love Wikileaks!” he proclaimed on October 10.

That same day, at a rally in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, he read out the false claim, drawn directly from a Podesta leak, that Clinton adviser Sidney Blumenthal had blamed her for the death of American diplomats in Benghazi.

Analysts have traced Trump’s quote to a text which was tweeted a few hours earlier. One of the most influential accounts to tweet that text was called @TEN_GOP, which has also been exposed as a Russian account. Trump’s quote may, therefore, have come via a Russian troll, as well as a Russian hacker.

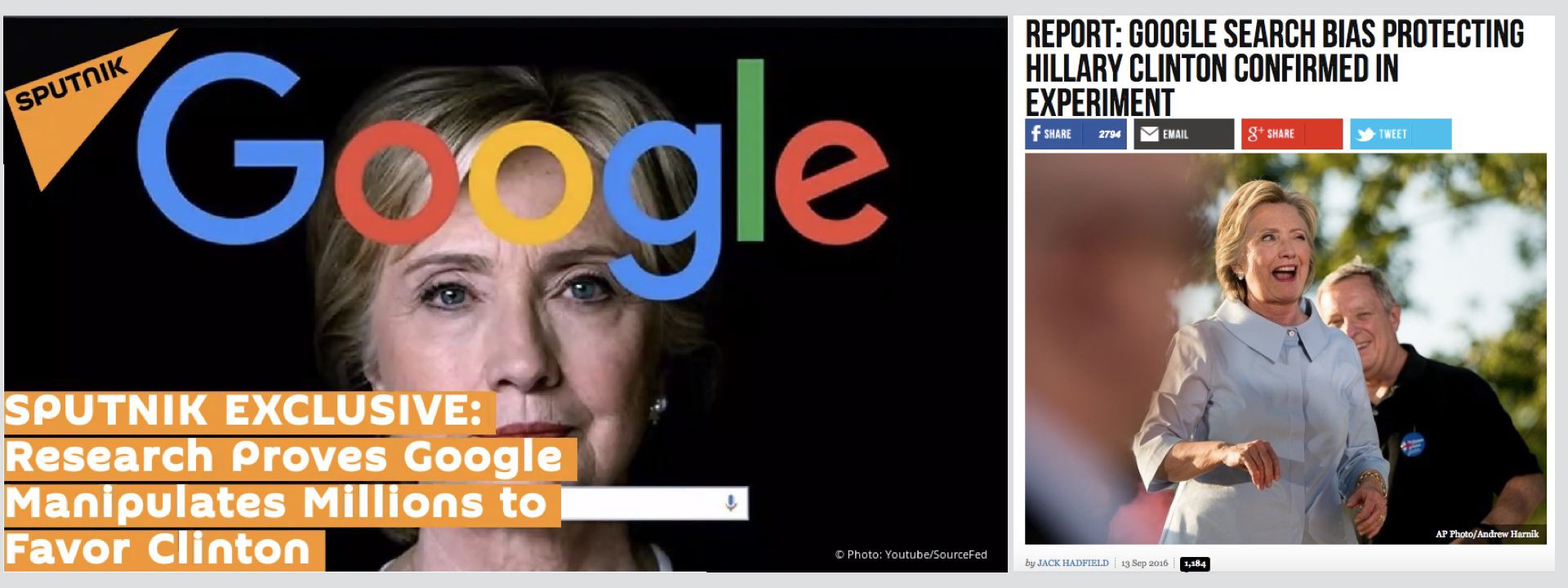

On September 29, 2016, Trump accused Google of “suppressing” bad news about Clinton. That claim had first surfaced in June, and been debunked.

Why did Trump revive it in September? Two weeks before his speech, the claim had resurfaced in a lengthy article run by Kremlin propaganda outlet Sputnik. It was picked up by conservative outlets the Trump campaign is known to have followed, including Breitbart, which attributed it to Sputnik.

It is likely that the Trump campaign took the allegation from those American outlets. What is certain is that the American outlets took their story from Sputnik.

These examples were cumulative; to them should be added Russia’s social media operations, which attacked Clinton and boosted her main rivals, organized Trump rallies in Florida and New York, and urged potential Clinton supporters not to vote.

“Particular hype and hatred for Trump is misleading the people and forcing Blacks to vote Killary. We cannot resort to the lesser of two devils. Then we’d surely be better off without voting AT ALL.” — Russian troll factory post, October 16, 2016, highlighted in Mueller’s indictment (para 46a).

Some of these social media accounts were highly influential. @TEN_GOP was retweeted by Trump campaign officials, including future National Security Advisor General Michael Flynn. @Crystal1Johnson was retweeted by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey on the opposite side of the political spectrum.

According to Facebook, Russian troll posts on the platform reached an estimated 126 million Americans between January 2015 and August 2017. Twitter accounts such as @TEN_GOP and @Jenn_Abrams boasted tens of thousands of followers.

The accounts posed as genuine Americans so successfully that the media treated them as spokespeople for their communities. Russian accounts were repeatedly quoted, as Americans, in online articles; one memorable Los Angeles Times piece cited just two Twitter accounts to illustrate the position of pro-Trump Americans, but both were Russian trolls.

Thus, Russia’s influence operation penetrated at least one vocal pro-Trump community so effectively that it came to speak for it.

We cannot say whether the Kremlin’s interference was enough to change the results of the election, but it certainly changed the campaign. Repeatedly, and for months, the Russian operation imposed extra burdens on the Clinton campaign, and furnished extra ammunition for Trump.

To argue that the Russian operation made the difference between a Trump win and a Clinton one goes beyond the evidence; but to argue that it made no difference is simply not credible.

Moreover, to continue arguing about this point is to miss a bigger one. Russia’s operation had a demonstrable impact on America’s political parties during an election campaign; Wasserman Schulz’s resignation was, in part, a product of that. With the midterm elections approaching, the priority should be to find ways to stop any such interference having an effect again.

Some steps have been taken. Facebook and Twitter have — belatedly — shut down the known cluster of Russian accounts; Facebook has announced more transparency in its political advertising. Mueller’s indictment has shed new light on the ways in which the troll operation worked. Researchers at NBC News, the Wall Street Journal, the Huffington Post and other outlets, together with online researchers such as UsHadrons, PropOrNot, Conspirator0 and many others, have compiled treasure troves of data on the last operation.

The best response would be a unified one, led by the White House. Given the state of partisan rancor in the United States over the Russia issues, that appears unlikely.

Yet there are ways to identify online disinformation, and to expose automated “bots.” Russia’s operations have been extensively analyzed by groups such as the EU’s East Stratcom Team, CEPA’s Information Warfare Initiative, and the European Values think tank’s Kremlin Watch, among many others.

Russia’s information campaign in 2016 penetrated an unprepared information space. The challenge is to make the America of 2018 more resilient. With the government divided over the issue, the onus falls on individual users to protect themselves, rather than waiting for their leaders to take the lead.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.