#ElectionWatch: Fraud Claims in Colombia

Dissecting accusations of ballot tampering in first-round polling

#ElectionWatch: Fraud Claims in Colombia

Dissecting accusations of ballot tampering in first-round polling

After the first round of voting in Colombia’s presidential election on May 27, citizens took to social media to share claims of ballot tampering in favor of leading candidate Iván Duque.

The conservative Duque won the first round with 39 percent of the vote, comfortably ahead of progressive rival Gustavo Petro, who garnered 25 percent. The two rivals are to face one another in a runoff on June 17.

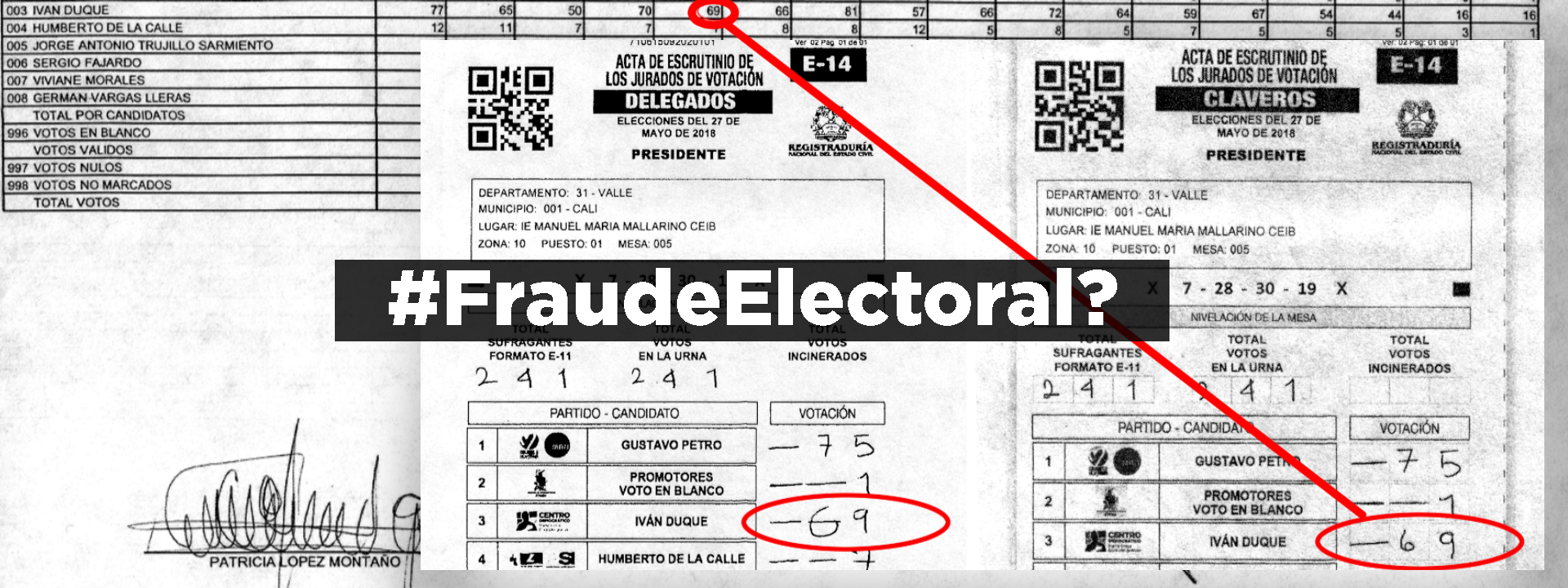

In response to the first-round scores, social media users began an amateur auditing exercise of voter tallying forms known as E-14, published online by the National Registry (Registraduría Nacional del Estado Civil), the institution in charge of election logistics. Some users shared images which they claimed proved that the forms had been tampered with.

Claims of electoral fraud, whether verified or false, are an increasingly pervasive phenomenon on social media (@DFRLab has documented similar claims in Germany, Scotland, and Russia, for example), and can be used to discredit the legitimacy of the final vote. This article assesses the claims made in Colombia, and the online traffic which spread them.

The E-14 forms are the documents in which officials write down how many votes each candidate had at their polling station. They are filled out manually and are the first step in a complicated vote count that lasts several days before results are made official by the National Electoral Council, Colombia’s supreme electoral authority.

The forms are scanned and published online, and are freely accessible for the public to scrutinize.

On May 29, social media users started reporting a pattern of apparent corrections in some of the scanned forms. Most of the reported amendments favored Duque.

https://twitter.com/lina_parga/status/1001650571957370881

https://twitter.com/lchsp_/status/1001622419566669825

Subsequently, Petro joined the conversation.

la rayita famosa que se dio como instructivo de la registraduría a los jurados de mesa, sirvió para alterar los resultados, espero que @Registraduria, corrija este entuerto pic.twitter.com/qK4VZKwyJK

— Gustavo Petro (@petrogustavo) May 29, 2018

On May 30, the tag #fraudeelectoral became a trending topic in Colombia on Twitter, and media picked up the story based on users’ findings. According to a scan conducted using the Sysomos online tool, between May 29 and June 5, over 288,000 tweets with the hashtag #fraudeelectoral were published, many of them included images of alleged alterations of the E-14 formats.

Also, on May 30, the General Prosecutor, Nestor Humberto Martinez, said in a press conference that he had evidence of a “nauseating” operation of electoral corruption, but he would only reveal it after the second round to “avoid anyone saying that I am intervening in politics.”

A lot of memes appeared and mocked the way the numbers were crossed and amended in the forms. There was even a computer font someone published overnight, the “E-14 Duque”, based on crossed characters.

The tone of the conversation was belligerent. Some people directly accused the Registry of complicity with the alleged fraud. It responded by publishing a press release explaining the situation and pointing out that the electoral procedure had already accounted for confusions of the jurors in the E-14 formats.

Its director, Juan Carlos Galindo, responded by asserting that “not every mistake can be labelled as an electoral fraud.”

The Registry followed up with a second press release, which called the allegations of fraud “fake news,” and posted a message across its homepage, which said, “marks and amendments on the E-14 forms DO NOT CONSTITUTE FRAUD.”

[facebook url=”https://www.facebook.com/RevoquemosAPenalosa/videos/642500972783854/” /]

How did the fraud claims go viral?

Analysis using Sysomos by @DFRLab showed that the hashtag #FraudeElectoral grew on May 29, and reached 238,000 tweets over the course of the day on May 30, before dropping off steeply the following day.

A high proportion of the traffic was generated by retweets, rather than authored posts. The Sysomos scan showed that 81.2 percent of the mentions were retweets. This is at the upper end of probability for organic traffic, but not so high that it indicated a large-scale attempt at bot manipulation.

Acoording to the Sysomos scan, the most-retweeted tweet to use #FraudeElectoral was posted by @FelipeCampoG, an unverified account which only has 1,955 followers, but achieved 7,309 retweets.

However, a scan of traffic on the tweet showed that its most important amplifier was Petro, who retweeted it to his 3.2 million followers. @FelipeCampoG tagged Petro in his post; thus, the discrepancy between his own following and the impact of his tweet can be explained by organic interest, not artificial manipulation.

Other top-performing tweets came from the verified accounts of journalists Daniel Samper Ospina (2.31 million followers), Felix de Bedout (1.91 million followers), and Vicky Dávila (2.69 million followers), demanding a clear explanation of the allegations. Given the size of their followings, there is no reason to suspect artificial amplification of these posts: they reflect genuine audience reach by genuine reporters over the claims.

Overall, we did not find evidence to suggest large-scale bot involvement in the Twitter traffic. The majority of posts came from accounts of medium authority (a measurement of an account’s interaction with, and influence on, other accounts; bots tend to have the lowest authority scores); the great majority of users only posted once.

A few accounts did post rapidly, and at very high volumes, but they were limited both in influence and in volume.

The user @sebasorozco93 (no avatar, mostly dormant) tweeted or retweeted the hashtag 389 times between 6:00 p.m. and midnight on May 29, more than one time per minute. It then stopped tweeting on May 30.

This spike is unusual, especially given that the account only tweeted 68 times without the hashtag. However, this does not resemble an automated account, as it has several authored unique tweets.

Another user, @Kevin73929829 (also no avatar), was created in February 2018, but remained dormant until May 30, 2018. Of the 190 retweets it shared since, 174 were related to the allegations of fraud. This activity is botlike; however, as of June 7, the account had no followers, making it, at best, of marginal significance.

There are several other accounts with similar patterns, but only some 10 percent of the tweets that used the hashtag had low authority scores consistent with bot activity . We have no evidence so far of large-scale botnet activity: we could not find coordinated efforts between several accounts, or repeated messages.

On Facebook, meanwhile, reports of the alleged fraud were amplified by groups and pages that explicitly support Gustavo Petro’s candidacy in their avatars or their billboard images. However, it is not possible to prove direct involvement of the official campaign in these publications.

https://www.facebook.com/naranjamov/posts/1753003488096758

News reports of the alleged fraud were also mostly shared by Petro supporters on Facebook, according to Crowdtangle.

Conclusion

The concerns over allegations of electoral fraud appear to have begun organically, and to have stemmed — ironically — from Colombia’s own transparency in publishing scans of the E-14 forms.

Much of the traffic on #FraudeElectoral was driven by high-profile journalists with followings in the millions, and expressed their concern over the allegations. A significant part of the traffic, not surprisingly, was driven by Petro’s supporters, and indeed, by Petro himself.

In and of themselves, the alleged violations appear to have been small in scale — certainly not enough to materially change the first-round results, according to the Mission of Electoral Observation. Furthermore, according to the Registry, the human mishaps on the forms did not compromise the integrity of the vote count.

However, the allegations had a potential online reach of hundreds of millions of users (315.8 million, according to a Sysomos scan), and generated hundreds of millions of posts.

The significance of these claims is therefore not so much the scale of possible violations they revealed, but the scale of the conversation they sparked. With the second round of the election due in ten days’ time, it will be important for the authorities in Colombia to monitor, expose and explain any allegations of fraud extremely quickly, to avoid a viral outburst of possibly misplaced wrath.

#ElectionWatch in Latin America is a collaboration between @DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.