#ElectionWatch: Russian Bots In Mexico?

Fact-checking claims of bots boosting Mexican messages

#ElectionWatch: Russian Bots In Mexico?

Fact-checking claims of bots boosting Mexican messages

In the buildup to Mexico’s presidential election on July 1, reports have been circulating of “Russian bots” amplifying political messaging in Mexico, raising fears of Russian state-backed interference, such as was seen in the United States in 2016.

@DFRLab has investigated these reports. We have been unable to verify claims of large-scale bot activity emanating from Russia. We have found one apparently Russian botnet boosting Mexican political messages, but this botnet appears to be commercially-run, boosting posts from a wide range of countries and on a wide range of subjects.

The exposure of this botnet underlines the ease with which internet users around the world can access bot amplification, the widespread presence of such commercial botnets in many political debates, and the importance of assessing all the evidence before attempting to attribute them.

Reports of Russian Interference

A number of international outlets began reporting on concerns over possible Russian interference in early May. On May 1, the New York Times ran an article headlined, “Bots and trolls elbow into Mexico’s crowded electoral field.” On May 10, CNN Mexico posted a video headlined, “Elections in Mexico 2018: is Russia interfering?”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6FPmMENnfKk

Both articles quoted digital researcher Manuel Cossío Ramos as saying that he had found apparently Russian bot-driven traffic boosting mentions of poll front-runner Andrés Manuel López Obrador. According to the New York Times, Cossío said that he found 4.8 million mentions of López Obrador posted to news sites and social media platforms from users outside Mexico, using a tool called Netbase. Two thirds of those mentions came from Russia.

CNN Mexico and, later, the Yucatan Times, quoted a figure of 112 million mentions of López Obrador, with 64 percent coming from Russia, and 18 percent from Ukraine.

The Yucatan Times article added that Cossío scanned Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Tumblr, and other platforms for mentions of López Obrador from April 10 to May 9. In his CNN appearance, he also gave examples of four hashtags, although he did not specifically link them to bot activity. These were #VivaMORENA, #YoVoyConLopezObrador, #LopezObrador2018 and #MuereElPri.

Verifying The Claims

Using the Sysomos online tool, @DFRLab scanned for mentions of “Lopez Obrador” and “LopezObrador” for the same time period, and for mentions of the four other hashtags over a full year. Each scan covered Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook public posts, blogs, forums, and news sites.

None of our searches confirmed Cossío’s results. Sysomos registered 96,900 mentions of “Lopez Obrador” across all platforms. Of those which gave a geographical location outside Mexico, half were from the United States, with small clusters in the United Kingdom, Canada, India and Venezuela. Russia and Ukraine did not even feature in the top ten sources.

Location data can easily be altered on some platforms, but there is no indication here of a major Russian or Ukrainian source.

The same applies to traffic on “LopezObrador.” This generated just over 217,000 mentions on all platforms, primarily Twitter; again, neither Russia nor Ukraine featured as a significant source of posts.

Our scans of the four hashtags mentioned by Cossío returned almost no results at all, even when extended across a full year. In total, Sysomos returned four mentions of #MuereElPri, eleven mentions of #YoVoyConLopezObrador and twenty-one mentions of #LopezObrador2018 in a year’s traffic. None of the mentions came from apparently Russian accounts marked by, for example, Cyrillic names, Russian locations or a predominance of Russian-language content.

Only on #VivaMORENA did we see a degree of traffic — 856 posts over the year, with distinct spikes in traffic on June 5, 2017; December 11, 2017; January 1–2, 2018; and April 22, 2018.

However, again, there is no indication that any of this traffic was Russian-linked. The traffic was driven by Spanish-language accounts, and a Sysomos scan showed no sign of Russian or Ukrainian locations.

This does not invalidate Cossío’s findings: the fact that our figures are significantly lower than those quoted in the earlier reports could indicate that a previously-existing botnet identified by Cossío was shut down before we ran our scans.

However, it does mean that we have been unable to verify Cossío’s claims of bot involvement, and of Russian or Ukrainian bots.

A Russian-seeming Botnet

A separate @DFRLab study did, however, identify a demonstrable botnet which shared Mexican political posts. We were first alerted to this botnet by Twitter user Josh Russell, in tweets on February 18 and May 3.

We individually verified the nature and behavior of some of the accounts Russell exposed, confirming that their behavior was botlike.

Among the accounts we examined were @3DmktwdgMOpki06, screen name “Игорь”, which gave its location as the province of Penza in Russia, and @QB8zWz4LFLKfOKd, screen name “Петр Смирнов,” which gave no location.

The profile picture for @QB8zWz4LFLKfOKd is taken from American singer Kris Allen, apparently from his Wikipedia entry:

Both were created in April, both had alphanumeric handles of a type often seen in large botnets, and both posted identical retweets, with few or no apparently authored tweets — all typical of bot behavior.

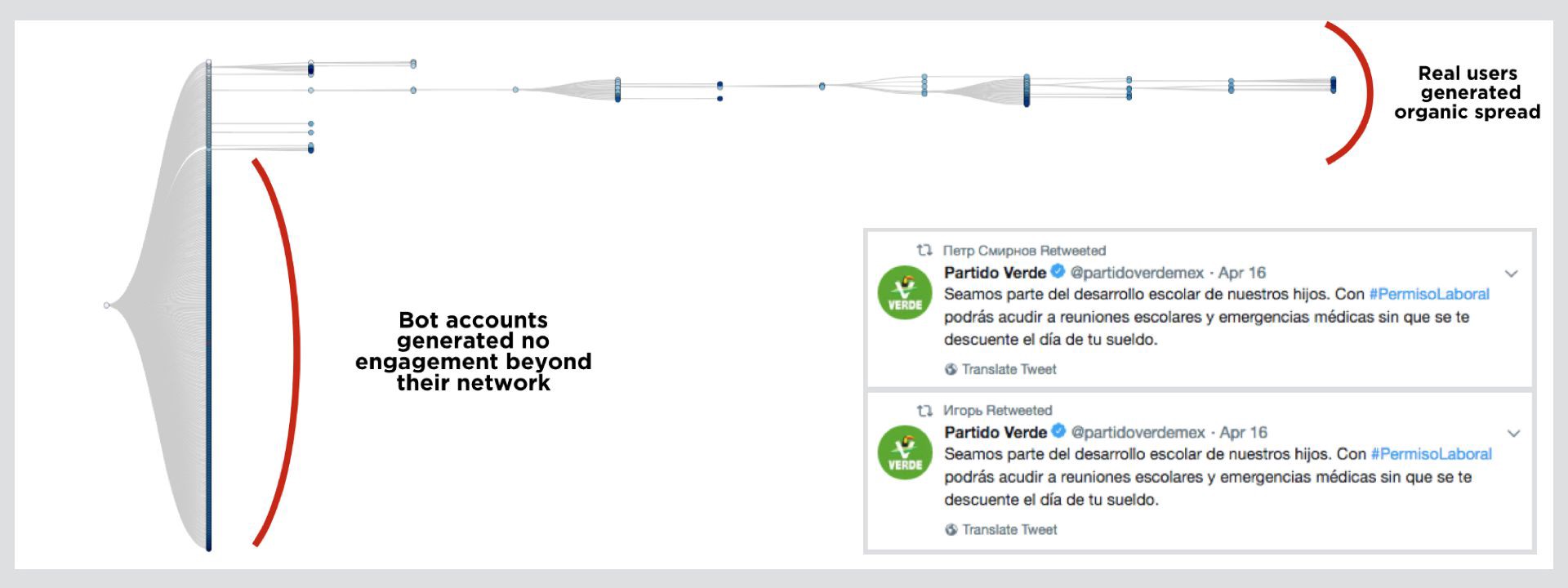

Among the posts they retweeted was one from the Green Party of Mexico, a verified account (@partidoverdemex):

According to a separate machine scan, the Green Party tweet was retweeted 697 times (the number has since fallen as Twitter suspended the bots involved). We scanned all the retweets, and found that approximately 18 percent came from accounts which gave their locations as being in non-Spanish speaking countries — especially Kazakhstan, Russia and Uzbekistan.

As mentioned, such indicators can be faked, but the proportion of them is high enough to suggest the presence of at least some accounts operated from the former USSR.

A machine scan also revealed that 263 retweeters had an authority score of 0 or 1 (out of 10), indicating that some of the accounts that retweeted Green Party’s post were likely bots. Below is a list of 260 accounts with a low authority score that retweeted the tweet. A large portion of those have Cyrillic or Russian-sounding usernames.

A visualization of the retweets of the post suggests that the initial amplification came from a community of genuine users, some of whom saw the retweet on others’ timelines and then retweeted it themselves. This is typical of organic engagement.

Subsequent retweets, however, failed to trigger any secondary user engagement at all. This is typical of bot insertions, in which a large number of bots retweet an initial post, but do not generate any follow-on retweets, because they have no human followers who might do so.

Commercial Bots

Thus, the Green Party’s tweet was clearly retweeted by a botnet, and many of the accounts in the botnet appear to have been Russian. So far, the diagnosis is clear.

However, this should not be taken to mean that the botnet in question was part of an attempt to interfere in the Mexican election by a politically-motivated actor. A deeper look at some of the accounts in the network confirms that they are commercial bots, apparently hired out to retweet or like posts by any user who is willing to pay for them, in any country.

For example, @3DmktwdgMOpki06 (“ Игорь”) retweeted posts in English, Russian, Spanish, Japanese and Arabic, on a range of subjects including cars, earthquakes, online earnings, Nicaraguan politics and a video of Japanese tourism mascot @love2chiitan kicking a martial arts post. Such are the joys of the internet.

Many accounts in the network retweeted the same posts, especially from a relatively small number of high-profile users. The following scan, using the Twitonomy.com online tool, lists the users most retweeted by six other accounts in the network.

Among the most-retweeted accounts are @Mark_Beech, a British rock journalist, @supermorgy, a Philippines-based lifestyle magazine, @love2chiitan, a Japanese tourism mascot and @ImAngelaPowers, the CEO of an insurance agency.

Nor did all the accounts in the network have apparently Russian identities. A large number seemed Spanish-speaking, especially Venezuelan. These included @rebeka252 (screen name “Génesis Vásquez”), which gave its location as Venezuela, but also shared the same Japanese video as apparently Russian members of the botnet:

Unusually, this account was created in 2009. It posted many of the same retweets as other members of the network, but followed each one with a reply to the retweeted account, posting just an emoji, or a scramble of letters:

Some of the account’s earlier posts appear human, but its later behavior is botlike; the similarity of its posts with other members of the network is too close for coincidence.

The Venezuelan claim is likely to be deceptive. A number of the accounts which claimed a location in Venezuela posted commercial-seeming tweets in Russian. These included @alepp1304 (screen name “Alejandro Patiño”), which posted two Russian-language tweets (not retweets) advertising a Russian cryptocurrency exchange service, each preceded by a jumble of letters.

Similarly, the account @ysah140399 (screen name “ysamarhidalgo”) interspersed the same cluster of retweets with Russian-language ads for the steroid Clenbuterol in Ukrainian pharmacies, real-estate in Russia and job vacancies in Belarus.

It, too, retweeted the @love2chiitan video, one of the posts most commonly shared by the network.

Also unusually, this account is linked to an active Facebook account, and appears to have taken a photo from it. However, its posts match those of the confirmed bots in this network. Moreover, for it to post Russian-language commercials about local services across the former USSR is exceptionally unusual behavior for a Venezuelan user, even an automated one; it is far more in character for a Russian-language user assuming a Venezuelan identity.

This also suggests that the botnet is managed from the Russian-language space.

Conclusion

This botnet appears to be work in relatively small clusters, numbering in the hundreds or low thousands (for comparison, @DFRLab has encountered botnets which numbered tens of thousands of accounts). This suggests that the clients — not necessarily the holders of those accounts which were retweeted — opted to buy small packages of retweets, to avoid too obvious an explosion in traffic.

The network does appear to be of Russian-language origin, although, as with all botnets, this identification can only ever be tentative.

However, it would be wrong to think of it as a state-backed influence operation, or even as a foreign attempt to interfere in Mexico’s domestic politics. The mixture of tweets which it amplifies, in many languages and on many themes, is not consistent with a political influence campaign; rather, it is characteristic of bots for hire, rented out to users who want to amplify certain posts.

Its presence on the fringes of Mexico’s political debate confirms, once again, the borderless nature of social-media bots, as well as of social media. @DFRLab has already identified apparently American-run bots in South Africa and Russian-run bots in Germany; the presence of apparently Russian-run bots in Mexico confirms the trend of commercial bots being used for ever more political amplification, in ever more countries.

It also underscores the importance of detailed analysis, evidence-based research, and precise terminology. These are likely to be, technically, Russian bots, in the sense of commercial bots operated from the Russian-speaking world; there is no evidence to suggest that they are bots sponsored by the Russian state.

#ElectionWatch in Latin America is a collaboration between @DFRLab and the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center at the Atlantic Council.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.