Blowing The Whistle On Sputnik

A former reporter shines a light on how Kremlin propaganda works

Blowing The Whistle On Sputnik

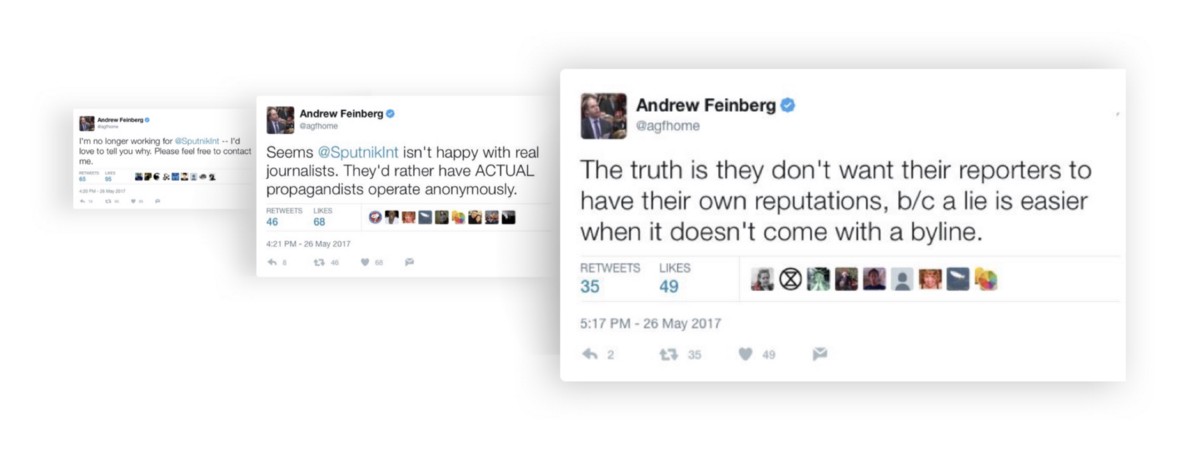

BANNER: Source: Andrew Feinberg / Twitter

On May 26, Andrew Feinberg, a correspondent covering the White House for Sputnik, tweeted that he no longer worked for the known Kremlin outlet. He then invited interested parties to ask him why.

I'm no longer working for @SputnikInt — I'd love to tell you why. Please feel free to contact me.

— Andrew Feinberg (@AndrewFeinberg) May 26, 2017

He added in a separate post, “Seems @SputnikInt isn’t happy with real journalists. They’d rather have ACTUAL propagandists operate anonymously.”

Seems @SputnikInt isn't happy with real journalists. They'd rather have ACTUAL propagandists operate anonymously.

— Andrew Feinberg (@AndrewFeinberg) May 26, 2017

The @DFRLab, which has long tracked Sputnik’s output, interviewed Feinberg. He explained the working conditions and editorial practices at Sputnik and the ways in which it differs from bona fide news organizations.

This testimony can be compared with the experience of other whistleblowers from the Kremlin machine, notably former anchors Liz Wahl and Sara Firth of Kremlin television station, RT, to gain further insight into how Russia’s state propaganda machine works.

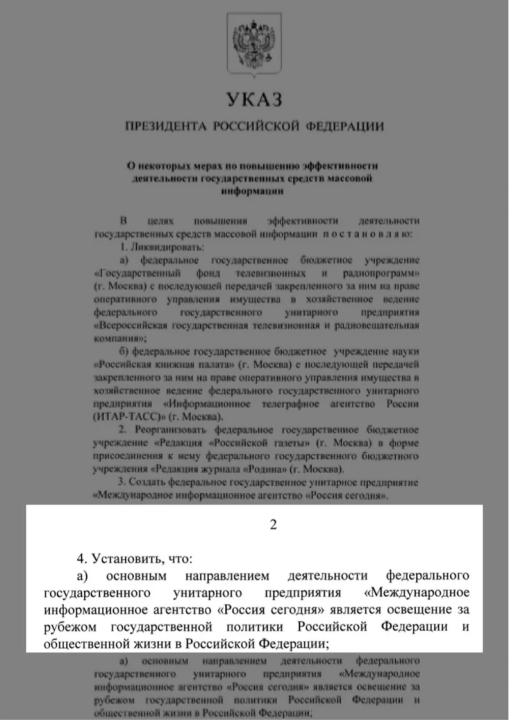

State Agency

Sputnik is a state-funded outlet created in December 2013 as part of a broader restructuring of Russian government media. According to the presidential decree, which established its parent company, Sputnik’s purpose is “reporting the state policy of the Russian Federation, and public life in the Russian Federation, abroad.”

While nominally distinct from RT, Sputnik has the same editor-in-chief and shares a number of writers. As such, the two outlets are best viewed as complementary agencies with a common agenda and editorial stance.

In an email to the DFRLab, the Sputnik press office described its mission:

Sputnik’s motto is «Telling the untold». This has been an enormous amount of work to see through as of recently, that we would eagerly leave to robustly financed and highly professional mainstream media, would they only give us a chance to provide the full picture, including Russia’s narrative, for the sake of broad press freedom. It is almost medieval to suggest that a media outlet that does not solely and blindly follow the Western discourse is being accused of heresy.

Feinberg joined Sputnik in December 2016. He told the @DFRLab that he was aware of the agency’s ownership but did not consider it an obstacle to working there:

When I took the job at Sputnik, I was fully aware it was state owned. I didn’t think that in itself was a problem as long as there was the editorial independence I was promised, but things quickly started taking a different turn.

Wahl expressed a similar sentiment in a 2014 interview with the Daily Beast, after she spectacularly quit RT during a live broadcast:

When I came on board, from the beginning I knew what I was getting into, but I think I was more cautious and tried to stay as objective as I could.

Wahl resigned after a series of editorial decisions which, in her eyes, sacrificed objectivity and accuracy in favor of the Kremlin’s chosen geopolitical narrative:

I cannot be part of a network that whitewashes the actions of Putin. I am proud to be an American and believe in disseminating the truth and that is why, after this newscast, I’m resigning.

Feinberg’s account of his decision to leave Sputnik after less than six months is very similar.

Command and Control

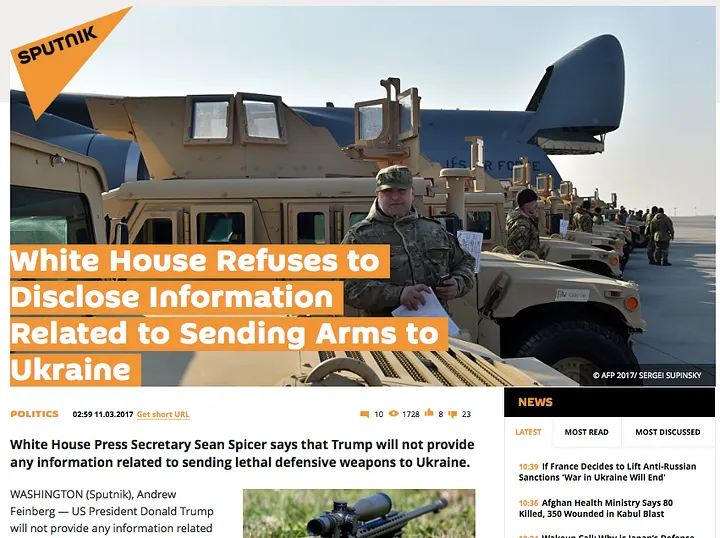

Feinberg said that his first “clash” with Sputnik’s editorial policy was about his independence to ask questions.

One of the first questions I asked in a White House briefing was if the President would use the National Defense Authorization Act to send lethal weapons to Ukraine, and if not, did that have something to do with not antagonizing Russia. When I got out of the briefing I was told that I shouldn’t ask questions when they didn’t know what they were going to be, ostensibly so that people could transcribe them.

The first part of his statement can readily be verified. According to the White House transcripts of daily press briefings, Feinberg asked his question on March 10. He subsequently filed a brief report, which Sputnik published.

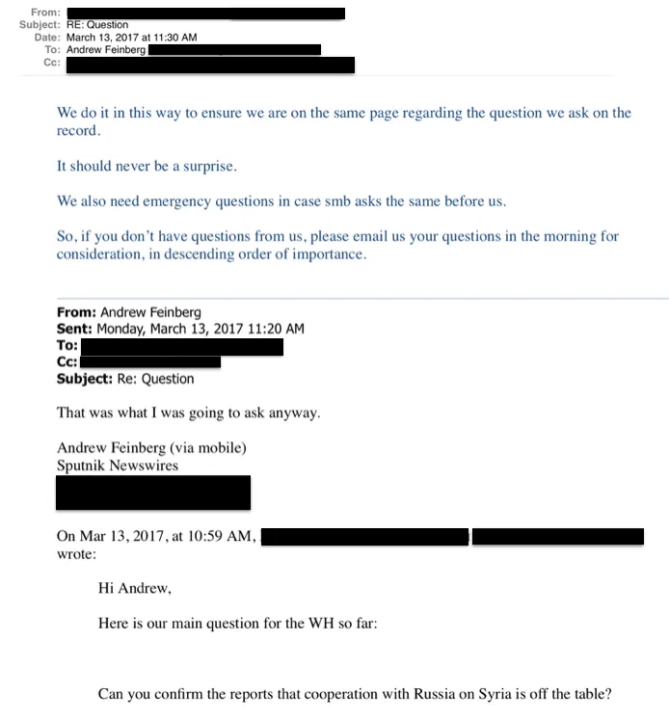

On the second part of Feinberg’s statement, the @DFRLab asked Sputnik whether it was part of editorial policy to pre-clear journalists’ questions and headlines. The answer was categorical:

Absolutely not. We do discuss job assignment with our reporters, as we believe that brainstorming is a good practice in journalism. The headlines at Sputnik as at significant part of leading international media remain with the editors.

However, to back up his statement, Feinberg shared with the @DFRLab a screenshot of an email exchange with an editor on March 13, confirming that questions asked on the record should “never be a surprise” and adding, “If you don’t have questions from us, please email your questions in the morning for consideration, in descending order of importance.”

The mail explained that “We do it in this way to ensure we are on the same page regarding the question we ask on the record.”

Editorial control was not limited to questions. Feinberg said that the content of individual stories was also subject to pre-clearance:

They have to approve the headline and the slant before you write the story (…) No one really has an assigned beat. Even when you’re watching something online, the pool reporters can come in and pitch a headline first and then they get to write the story.

This editorial micromanagement increasingly irked Feinberg, who saw it as a method of controlling reporters:

I’ve never had that degree of heavy-handed editorial interference. It’s all couched with excuses and logic that seem reasonable if you’re a wire with limited resources, but at the same time, that culture is targeted to massage a certain sort of reporting.

Again, this agrees with an account Wahl wrote for the UK-based Institute for Statecraft, in which, as an anchor, her questions were set by her editors and, in at least one case, “dictated” to her:

The Russian leaders [of RT America] were closely involved in our day-to-day coverage, not just providing guidance on what stories to cover and how to report them, but also sourcing the ‘expert’ commentators we had to interview.

Central editorial guidance is a standard feature of reporting in worldwide news wires — deciding, for example, which is the main story of the day, asking individual bureaus to provide reactions to it, or asking questions on behalf of colleagues who cannot attend an event. However, the degree of control which the whistleblowers say that RT and Sputnik exercise remains extremely unusual.

Facts and Facets

Feinberg also stated that he grew disillusioned with Sputnik’s coverage of issues of importance to Russia. Again, the Crimean issue was an example. Feinberg highlighted Sputnik’s writing on the “referendum,” conducted during the Russian military occupation of the peninsula and widely regarded as illegitimate, which justified Russia’s annexation.

When they were writing on Crimea, their context left out the guys with the tanks and guns who were everywhere during the referendum. I couldn’t put that in, it wouldn’t have made it past the first edit, but leaving that out is to ignore reality.

This statement can be checked against Sputnik’s reporting. A number of articles on the agency’s website in February, March, and April 2017 provided very similar background paragraphs on the events which led up to the annexation:

Crimea rejoined Russia in 2014 when about 97% of its citizens voted in favor of reunification in a referendum. Nevertheless, the West condemned the result, imposing several rounds of sanctions against Russia.

None mentioned the conditions surrounding the vote, the report from a Russian agency exposing the turnout and support for annexation was much lower, or the vote’s rejection by 100 members of the United Nations General Assembly.

Feinberg said that Sputnik’s coverage of other issues of importance to the Kremlin was similarly distorted.

You learn very quickly that you have to put the Russian perspective, and the most absurd version of it. That’s what they want. There’s no opportunity to do real journalism.

This tallies with specific cases, which the @DFRLab and other observers, have identified (such as here and here).

He highlighted two cases in which Sputnik’s coverage appeared aimed at promoting a specific Kremlin narrative. The first concerned a mustard gas attack launched by Islamic State against an Iraqi military base housing U.S. and Australian advisory forces in April. The attack is not reported to have caused fatalities, although 25 Iraqi soldiers required treatment.

Feinberg said Sputnik’s editors insisted that it belonged in the same category as the chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun in Syria, which killed dozens of civilians, mainly children, prompting U.S. retaliation:

They wanted me to frame it as a chemical attack on U.S. forces and ask why we weren’t responding as we did to the Khan Sheikhoun attack. It’s not even comparing apples and pears, it’s apples and penguins.

In the event, Sputnik’s follow-up coverage of the attack focused on the ability of U.S. and Australian troops to respond to chemical attacks. RT’s coverage, however, included an interview on the question of why the “Western media” had treated the Iraq attack differently from the Khan Sheikhoun one.

For Feinberg, the last straw was Sputnik’s coverage of the death of U.S. Democratic Party staffer Seth Rich. As the @DFRLab has reported, Sputnik continued to insinuate that Rich was murdered in 2016 because he leaked emails to Wikileaks, even after Rich’s family protested and Fox News retracted the story which triggered the claim.

The Seth Rich story was one of the things which led to my no longer being there. Sputnik’s purpose in pursuing the Rich narrative was to obfuscate and be able to say, ‘If he did it, there was no Russian hacking. Russia, what’s that?’

Again, this use of questionable practices to cover a story in a way favorable to the Kremlin coincides with Sara Firth’s comments in 2014, after she resigned over RT’s coverage of the MH17 crash:

Rule one of the Russia Today style guide is to blame Ukraine, or anything else, rather than Russia (…) It’s scary that it’s genuine RT guidance on how to do a story, and you have to believe it to succeed there.

Firth claimed that RT staff were “asked on a daily basis… to obscure the truth.”

This also coincides with Wahl’s assessment of RT:

My experience as an RT reporter and anchor was that RT’s main goal is not to to seek truth and report it. Rather, the aim is to create confusion and sow distrust in Western governments and institutions by reporting anything which seems to discredit the West, and ignoring anything which is to its credit.

Feinberg’s account matches with these earlier statements, and with much of the coverage @DFRLab observed in both RT and Sputnik. It also echoes the findings of the UK’s regulator, Ofcom, which has repeatedly found RT guilty of violating the obligation to preserve due impartiality in its coverage.

Chain of Command

Feinberg provided some insight into the chain of command within Sputnik and the extent to which its coverage appears dictated by political considerations in Moscow.

This is significant, because like RT, Sputnik insists that it is editorially independent, rejecting accusations that it is steered by Kremlin policy — a point reinforced in the press service’s email:

It is only natural that our colleagues in Washington D.C. are better equipped to navigate U.S. news terrain than we are in Moscow. So, however flattering it might be to us that we rule the world from the Moscow newsroom, it’s absolute nonsense to assume that our D.C. team toes the line of Moscow.

While Feinberg could not give an insight into individual editorial decisions, he suggested that the overall angle of coverage was decided in Moscow and conveyed to the Washington bureau by Russian editors:

I think the information warfare is there, but it’s done by people much higher up the chain. I was at the end of a very long chain of command. Among the editorial team, the two Russians were very much in charge.

This also applied to allegations that Sputnik’s coverage on social media was amplified by “botnets,” networks of fake accounts used to repost articles, giving them more publicity:

Do I think there was collusion between the Sputnik reports and the botnets? I think whatever coordination is done there happens in Moscow.

This, again, is consistent with Wahl’s description of work at RT America:

The News Director and Business Director were Russian. The nature of the relationship between Moscow and these Russian managers proved to be murky, as most of us were kept in the dark about the origins of the directives we would receive.

Feinberg even claimed that contact between the American staff and the Moscow bureau was actively discouraged:

They’d get upset if I mailed the IT department without permission. I don’t think they wanted Americans to contact Moscow.

Asked to comment on Feinberg’s departure, Sputnik’s press office said that his claims were “false accusations” and that his departure was due to a failure to provide “the same level of professional journalism and the amount of exclusive stories that our clients and readers are looking for.”

Conclusion

Feinberg’s account of the months he spent at Sputnik is consistent with the accounts of other whistleblowers who have departed the Kremlin-funded, English-language media.

It describes a world in which journalistic independence is subordinated to editorial control, local bureaus are subordinated to central command, and journalistic standards are subordinated to an overall political narrative.

This behavior is not consistent with an independent news outlet, such as Sputnik claims to be. However, it is consistent with a centrally-managed government communications service, in which key messages and narratives are distributed from the center to regional hubs for amplification.

Feinberg’s comments thus provide further evidence which helps us to understand the nature and activity of the Kremlin’s outlets.