RT and Sputnik: Clean Bill of Health?

Fact checking the Russian Foreign Ministry’s claims

RT and Sputnik: Clean Bill of Health?

Share this story

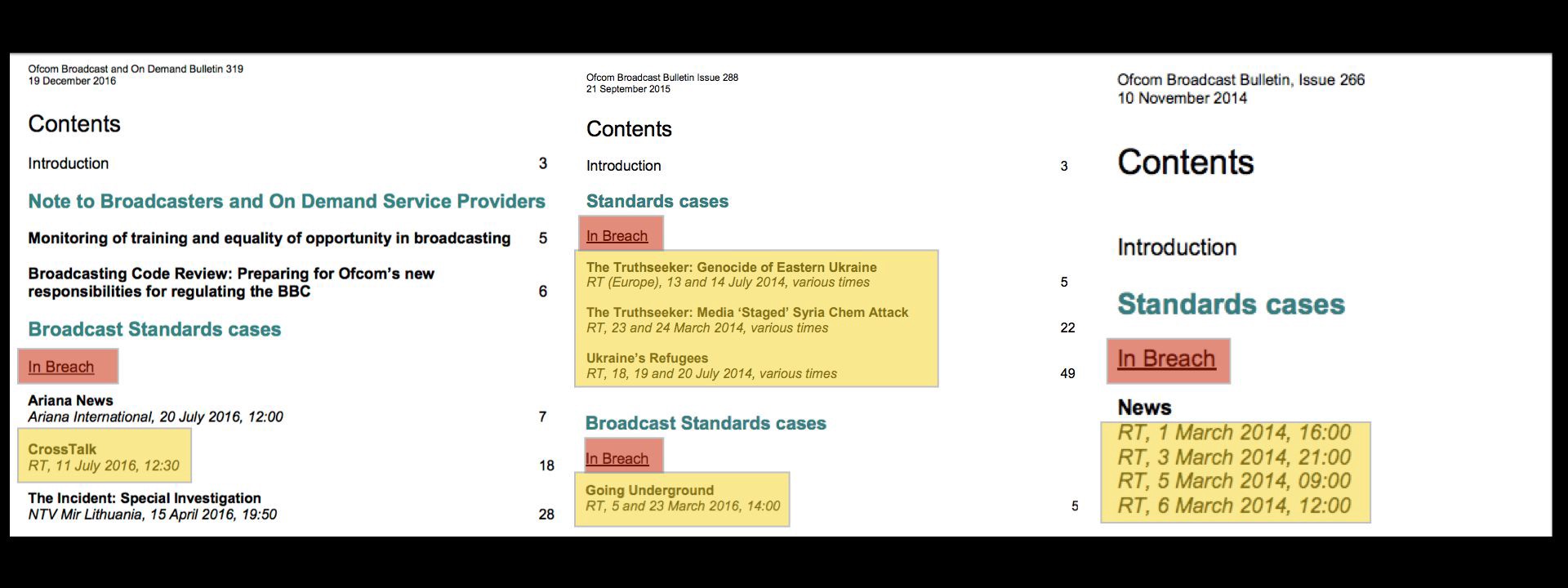

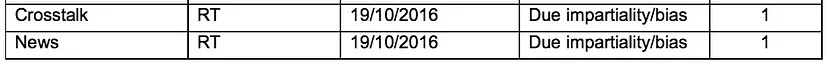

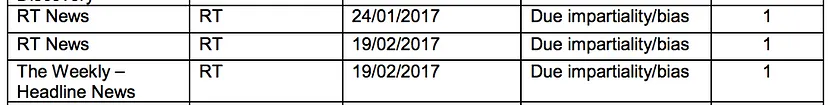

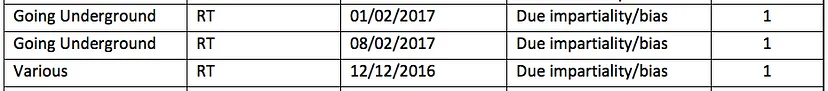

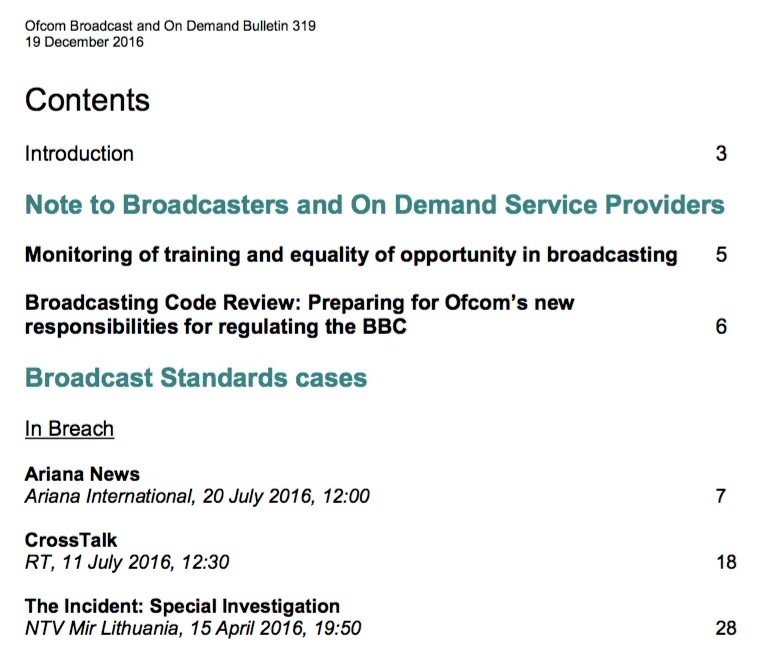

BANNER: Contents pages of Ofcom bulletins, showing some of RT’s violations.

The Russian Foreign Ministry says that state-funded broadcasters RT and Sputnik have a clean bill of health. Three times since late April, it has attacked critics of the two outlets by claiming that the UK’s telecoms regulator, Ofcom, has found them not guilty of false reporting.

The fact that the Russian government is defending its outlets is not new. (Earlier examples are found here, here and here.) What is new in the latest statements is their appeal to the authority of Ofcom.

The invocation is startling, because Ofcom has repeatedly found RT guilty of violating the UK’s broadcasting standards.

What lies behind the Russian Foreign Ministry’s statements, and are they correct?

Claims and counter-claims

The first incident came in April. On April 18, British daily The Times published an editorial criticizing Russia’s policies. The editorial included a reference to “fraudulent propaganda, pushed by fake news outlets such as Russia Today and Sputnik.”

A week later, the Russian Foreign Ministry responded with a statement accusing The Times of “fiction” and “information attacks.” The ministry said the Times editorial team “should be perfectly aware that the British media regulator, Ofcom, never found any proof that the media in question disseminate false information.”

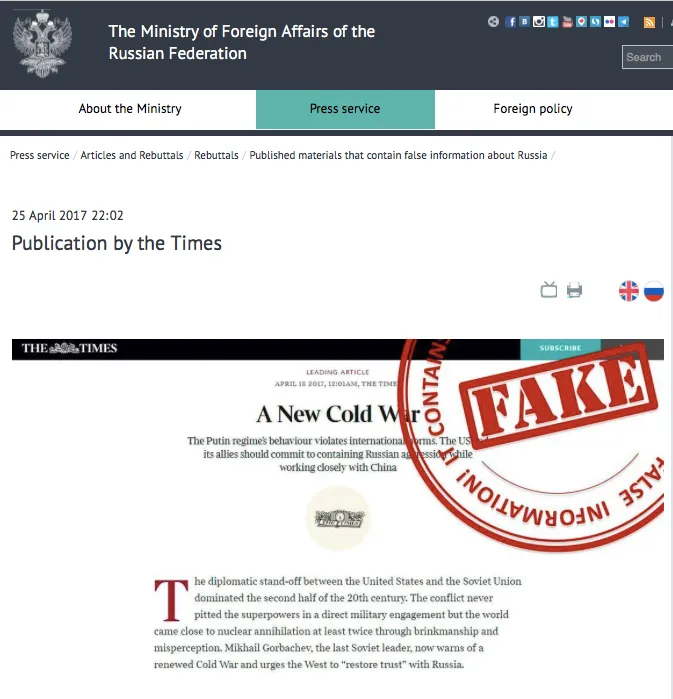

The second incident came in May, after The Times published an opinion piece accusing the Russian government of interfering in the US and French elections, and claiming that Russia controls “a formidable apparatus of fakery disguised as news, principally the broadcaster Russia Today (RT) and the purported news agency Sputnik.”

On May 20, the Russian Foreign Ministry responded, accusing The Times of “slander,” “fake news,” and “professional jealousy.”

The ministry argued, “We assume the UK media circles are aware of the British media regulator Ofcom’s check of the Russia Today (RT) and the Sputnik news agency’s operation. It is known for a fact that none of the information products issued by these two Russian media outlets fall under the category of fakery. Meanwhile, The Times is regularly caught spreading fake news.”

Ten days later, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov also referenced Ofcom in a comment defending RT and Sputnik against claims of propaganda:

“As for Sputnik and Russia Today, not long ago Britain’s Ofcom was dealing with similar accusations. It did not find any violations of journalistic ethics. I would like to repeat that this is the opinion of those that are considered independent agencies that are in a position to conduct an expert evaluation.”

Ofcom — the background

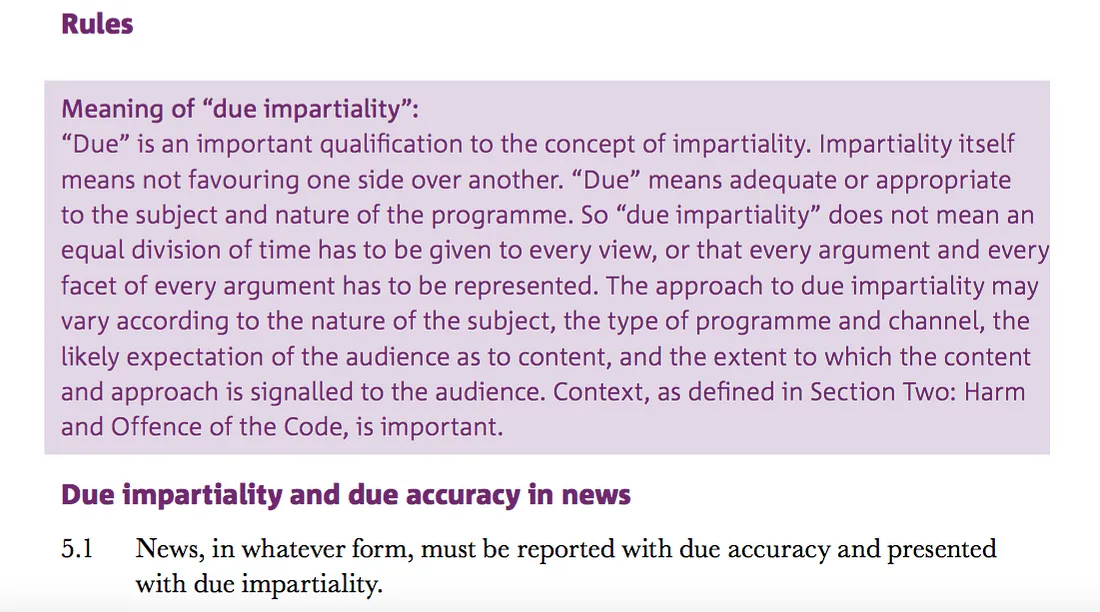

Ofcom is the UK’s independent telecommunications regulator. One of its functions is to enforce standards in broadcasts made over the airwaves — TV and radio, but not, significantly, internet-only products. The standards are published online, and cover a number of issues, including decency, hate speech, the protection of younger viewers, and advertising.

Section 5 of the code concerns news reporting, and states that “news, in whatever form, must be reported with due accuracy and presented with due impartiality.”

Ofcom has the right to investigate broadcasters who are suspected of violating the code; this is usually done on the basis of complaints from the public. In the two years from July 2014 to July 2016, RT was found to have violated the standards of news reporting for programs covering Ukraine in November 2014 and September 2015 and Turkey in July 2016.

These findings led to repeated criticisms by RT’s supporters. On October 29, 2016, for example, the Russian Foreign Ministry accused Ofcom of “clear bias” against RT. In 2015, an opinion piece by RT presenter Afshin Rattansi claimed that Ofcom’s task is to “hound mainstream UK broadcast media.”

In 2014, Lavrov himself accused Ofcom of “censorship,” while RT Editor-in-Chief Margarita Simonyan accused Ofcom of “an attempt to influence editorial our policy.”

The recent invocations of Ofcom are therefore all the more striking.

RT’s defense

On July 5, the BBC interviewed RT’s London bureau chief, Nikolay Bogachikhin, and asked him about RT’s relationship with the regulator.

Bogachikhin said: “We have a very productive relation with Ofcom, but sometimes we have a different view on what this amount of dueness is in the ‘due impartiality’ rule so… but we are working on it, so that’s not something unusual. I’m pretty sure that all the other broadcasters were found in breach many more times than us.”

The final sentence does not match the facts. A survey of all Ofcom broadcast bulletins from January 2014 to July 2017 showed that RT had had ten programs found guilty of violating the rules on accuracy, impartiality, and “materially misleading” audiences, in four different bulletins (November 2014, September 2015, July 2016, December 2016).

Only one broadcaster had more programs found in violation of the code over the same period: the Indian outlet Times Now, which had twenty programs listed in two rulings (February 2017 and April 2017).

Among other broadcasters, NTV Mir Lithuania, which shows programs in Russian, had six programs in violation (June and July 2015, March and December 2016, June 2017). China’s CCTV had four programs found guilty in a single judgement in February 2015; Fox News had three violations in September 2015 and August and November 2016; the UK’s Channel 4 had three violations in February, April and December 2015.

RT’s record, as far as Ofcom’s findings on accuracy and impartiality go, is therefore unusually poor.

The Russian Foreign Ministry’s claims

The Russian Foreign Ministry’s two latest references to Ofcom, and Lavrov’s remarks, differed in the detail, but made the same basic argument: it is wrong to accuse RT and Sputnik of fakes, violations or propaganda (all three terms were used), because Ofcom has checked them.

Part of this argument can be dismissed immediately. Ofcom’s mandate is limited to broadcasts made on the airwaves. Since January 2017, Sputnik, which formerly aired on digital radio in London, is an internet-only outlet, and, as such, is not subject to Ofcom.

The Russian Foreign Ministry’s claim that Ofcom cleared Sputnik of violations cannot, therefore, be accurate.

The question of a “check” on RT is more nuanced. From late 2016 onwards, Ofcom assessed a number of complaints against individual RT programs. These included three broadcasts listed in the Ofcom bulletin in November 2016 (pages 104–105), three listed in March 2017 (page 34), and a number listed in April 2017 (page 105).

In each bulletin, Ofcom stated that these individual programs “did not raise issues warranting investigation.”

The Russian Foreign Ministry’s claim that Ofcom conducted a “check,” and found no violations, is therefore partially correct.

However, as the screenshots from the relevant bulletins show below, Ofcom’s assessments covered individual programs, identified by the program name, broadcaster, date, and nature of the complaint.

To refer to an Ofcom check of RT’s “operation” more broadly, as the Russian Foreign Ministry did, is therefore inaccurate. Ofcom cleared individual RT programs; it did not clear the broadcaster as a whole.

Violence and violations

This leaves the claim that RT and Sputnik were not found to have committed “fakery” (in the words of The Times and of the Russian Foreign Ministry statement) or “violations of journalistic ethics” (in Lavrov’s words).

These are two different, but concentric, terms. “Violations of journalistic ethics” can cover a range of offenses, including deliberate inaccuracy and bias; “fakery” appears to refer more narrowly to inaccuracy, although the term is poorly defined.

Lavrov’s statement is therefore more sweeping; it is also misleading. As recently as December 19, 2016, Ofcom found RT guilty of violating the obligation to preserve due impartiality in a talk show, CrossTalk, during a discussion of the NATO Warsaw summit.

More broadly, as was discussed above, RT has a particularly poor record, with multiple programs found guilty of violations.

Lavrov’s May comment that Ofcom investigated “not long ago” and “did not find” violations would therefore be correct, if “not long ago” were taken to mean “in the past five months.” Over any longer time period, it is wrong.

The claim of “fakery” is more difficult to assess, because “fakery” is not a technical term with a legal definition used by Ofcom. The term “fake news” is even more vague. Recent analyses from various journalistic sources have, for example, named three sorts of fake news; five sorts; and seven sorts.

It is unclear which definition The Times used. Judging by the use of the phrase “disseminating false information,” the Russian Foreign Ministry’s definition focuses on information that is inaccurate or misleading, as opposed to biased.

Conclusion

Three points seem clear. First, in September 2015, Ofcom found RT guilty of “materially misleading” its audience, in a broadcast on the use of chemical weapons in Syria. The Ministry’s claim that Ofcom “never found any proof that the media in question disseminate false information” is therefore incorrect.

Second, and in justice to RT, it should be noted that this ruling was an exception. RT has not been found guilty of repeatedly violating standards of accuracy in the way that it has been found guilty of repeatedly violating standards of impartiality. Whether RT can fairly be termed a “fake news outlet” more broadly therefore depends on whether the term “fake news” itself only covers accuracy, or also impartiality.

Third, there is a pattern to RT’s violations of the obligation to preserve due impartiality. All the most recent cases concerned organizations which the Russian government saw as its opponents at the time — the Ukrainian government (Ofcom rulings in 2014–15), the Turkish government (July 2016), and NATO (December 2016).

Thus, while RT may or may not be a “fake news” outlet, depending on the definition, it does appear to support and amplify the Russian government’s narrative, even at the cost of journalistic standards. This behavior is characteristic of propaganda outlets.

This may explain why the Russian Foreign Ministry has taken to defending it — even at the cost of providing “evidence” from Ofcom that is irrelevant, incomplete, or incorrect.