Misinformation about Colombia’s national strike spreads online and on air

Colombian social media accounts and legacy media amplified false and misleading claims amid the ongoing Colombian protests

Misinformation about Colombia’s national strike spreads online and on air

Thousands of Colombians have taken to the streets in different cities across the country since April 28, 2021, initially in protest against a government tax reform proposal and its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As the protests continued, they have transformed into a larger movement against police violence.

Although the marches have been peaceful in many locations, at least 19 people have died, some due to police brutality. On social media, videos accurately showing police violence against protesters emerged. Amid the chaos, however, so did misinformation in the form of miscontextualized and recycled media, some of which aired on Colombia’s national public broadcaster.

In February 2021, Colombia’s Comité Nacional de Paro (“National Strike Committee”), comprised of unions, workers associations, and educators, called for a national protest against the Colombian government. On April 28, protests targeted the tax reform bill aimed at raising taxes, that according to the government would alleviate the economic crisis aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the course of several days, other unions, opposition parties, and civil society organizations joined protesters in the streets, while people in their homes showed solidarity through cacerolazos — an act of peaceful protest involving banging a casserole dish or pan to make noise — to complain about a range of issues, including the mismanagement of vaccination programs, lack of payments for medical personnel, current unemployment levels, as well as the killing of activists.

Although Colombian President Iván Duque withdrew his tax reform proposal — the main impetus for the demonstrations — and Finance Minister Alberto Carrasquilla resigned on May 3, the protests have continued, in part because of the police crackdown.

After police killed several demonstrators, the protests transformed into calls against police violence. An accurate count for the number of deaths related to the protests is difficult to determine, and various sources give different numbers. As of May 7, 2021, Colombia’s ombudsman’s office puts the death toll at 24. Official reports from that office also reported that 846 were injured during the protests and 89 people were listed as “disappeared.” Meanwhile, recent reporting by Temblores, a non-governmental organization that monitors police violence, suggests as many as 37 deaths as a result of police violence.

The recent protests were the first nationwide demonstrations to take place against the government amid the pandemic. Previously, in October 2019, the Comité Nacional de Paro called for massive protests against Duque’s economic measures — including the tax reform bill — that lasted until the following January. During the protests in November 2019, the DFRLab identified accounts on Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp that disseminated videos of supposed widespread looting, while suggesting Venezuelan migrants and vandals were behind some of the chaos.

During the first week of the 2021 protests, the DFRLab concluded that both social network users and media outlets have circulated misleading videos. Most of the videos analyzed were supposedly related to clashes involving protesters, policemen, and alleged infiltrators.

Inaccurate claims of support

In Cali, the biggest city in southwest Colombia, confrontations between protesters and police turned violent. At the time of writing, the total number of people killed during these protests has yet to be confirmed. However, during a press conference on May 4, Carlos Alberto Rojas, Cali’s secretary of security, said that a preliminary report showed that five people died and 33 were injured during two protests on May 3. Marta Hurtado, spokesperson for the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, condemned the violence in Cali and accused the police of “open[ing] fire on demonstrators,” including an attack on human rights observers in attendance alongside a UN delegation.

Media outlets have covered the protests in Cali from various angles, reporting on confrontations between demonstrators and policemen — some of them peaceful, some not — as well as incidents of looting and the protests’ local economic impact.

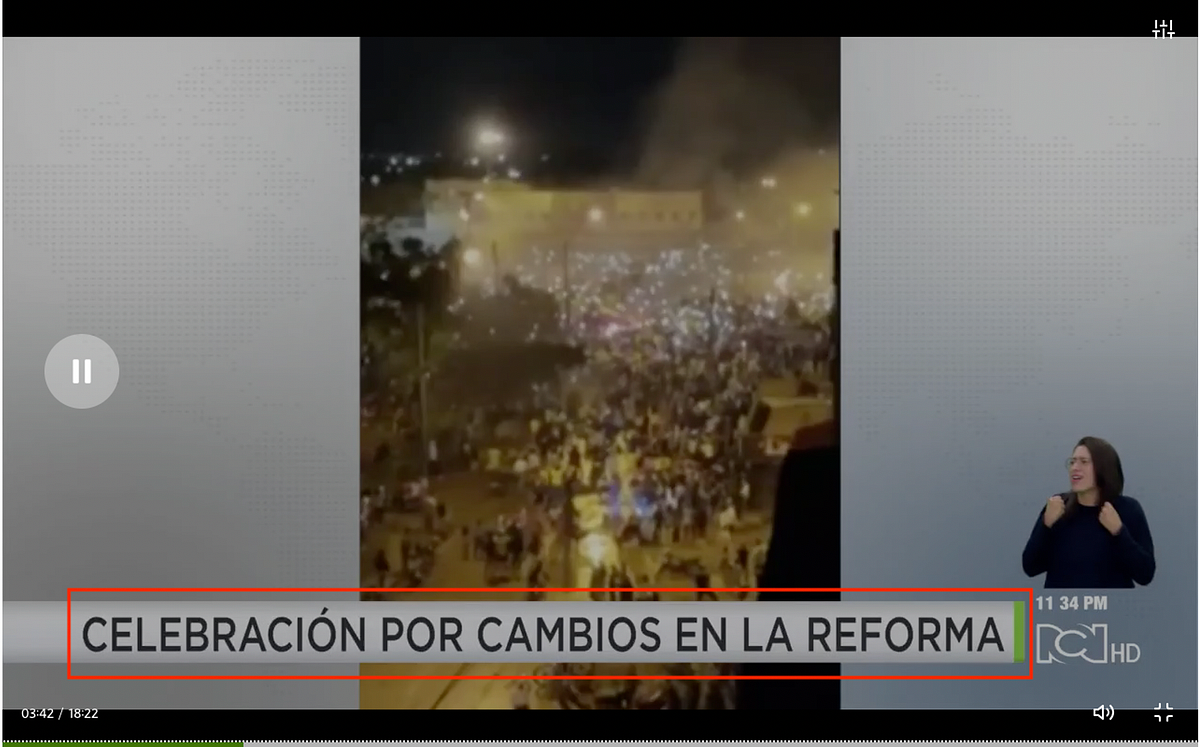

Two of the protests most widely covered by media were demonstrations in Loma De La Cruz and Puerto Rellena, which during the strike has been referred to as Puerto Resistencia (“Port Resistance”). On April 30, protesters in Puerto Rellena expelled members of ESMAD, a specialized police unit deployed to control protests. At 6pm local time, the protesters sang the national anthem to show solidarity against the tax reform proposal and, according to El Espectador, to celebrate police leaving Puerto Rellena. At the same time, in Bogota, President Duque announced in a televised speech that he would modify the tax reform proposal.

Later, Colombian TV broadcaster RCN misleadingly suggested that the protesters sang the national anthem to celebrate Duque’s announcement on changing the tax reform proposal. However, media outlets such as El Espectador, La Silla Vacía, and ColombiaCheck, debunked the RCN report based on posts and interviews with the demonstrators, who denied they were celebrating Duque’s announcement. ColombiaCheck, for example, interviewed an eyewitness who had recorded a video from the scene saying that people were celebrating the rejection of violence rather than anything to do with President Duque’s announcement. According to Colombian news magazine Semana, the RCN news program was the second highest-rated news program in the country as of March 19, 2021.

Recycling videos from protests in other countries

Twitter and Facebook accounts have also posted videos taken in other countries during unrelated protests, and incorrectly presented them as footage from the ongoing protests in Colombia. One example included recycled footage of a confrontation in October 2019 between members of the Ecuadorian police and army in Guayaquil. Two accounts belonging to a self-described Colombian journalist and academician incorrectly suggested that the attack occurred between members of the Colombian National Police and the Colombian Army during the protests in 2021. Meanwhile, another Twitter account posted the same video on April 28 and garnered over 27,000 views and 300 retweets. Accounts that quoted the post blamed the Colombian military and police for the violence during the protests.

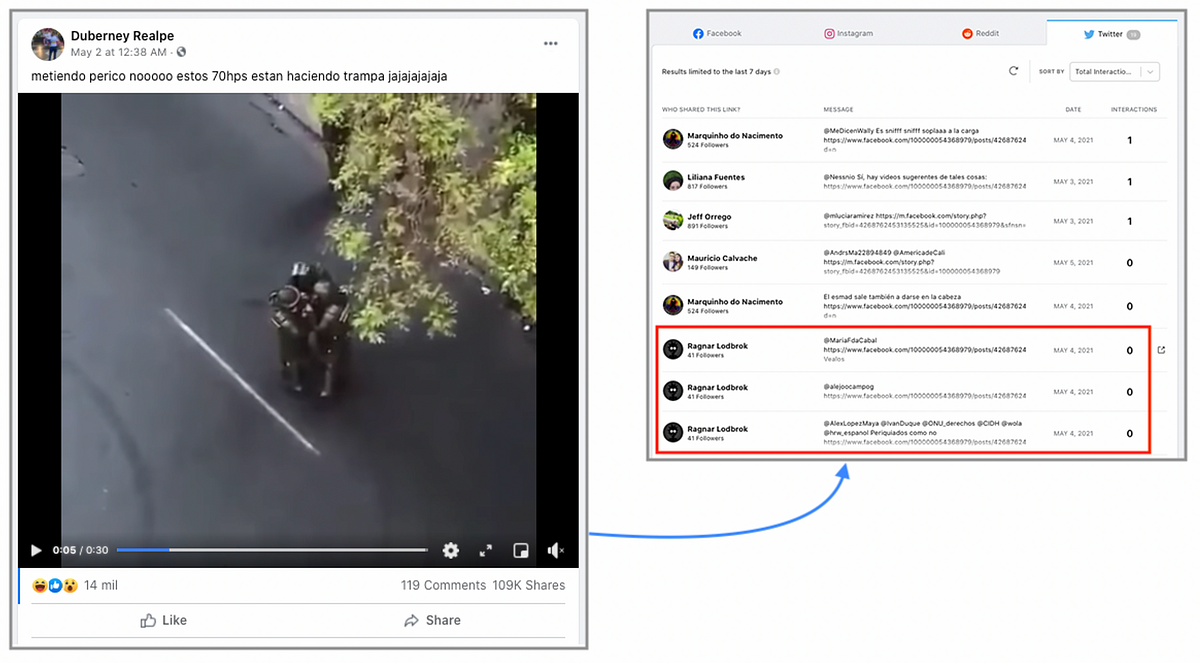

On May 2, Facebook accounts also amplified a video that actually showed carabineros — Chilean police officers — during the October 2019 protests in Chile. One of the accounts, with its location set to Cali, posted the video and falsely claimed it showed members of Colombia’s ESMAD police unit using cocaine. The misleading post garnered over 14,000 reactions and 111,000 shares. Chilean media outlet La Tercera debunked the video in 2019 and said that the police officers might have been applying an ointment used to protect themselves from tear gas.

ColombiaCheck and La Silla Vacía, meanwhile, debunked both videos and explained that the same content also appeared on social media during the protests in November 2019 in Colombia targeting the Colombian security forces.

Police abuse of power during the national strike

While protests exploded across different cities in Colombia, social media users shared videos documenting instances of police violence against the protesters. As noted earlier, the Colombian Ombudsman’s Office officially reported at least 24 deaths during the demonstrations some NGOs placed the number of deaths higher. According to civil society organizations and independent media, some of these deaths occurred as a result of excessive violence by the National Police. For example, on May 2, 2021, the Colombia-based independent investigative media outlet Cuestión Pública reconstructed an incident in which a police officer in Cali shot and killed a 17 year-old teenager.

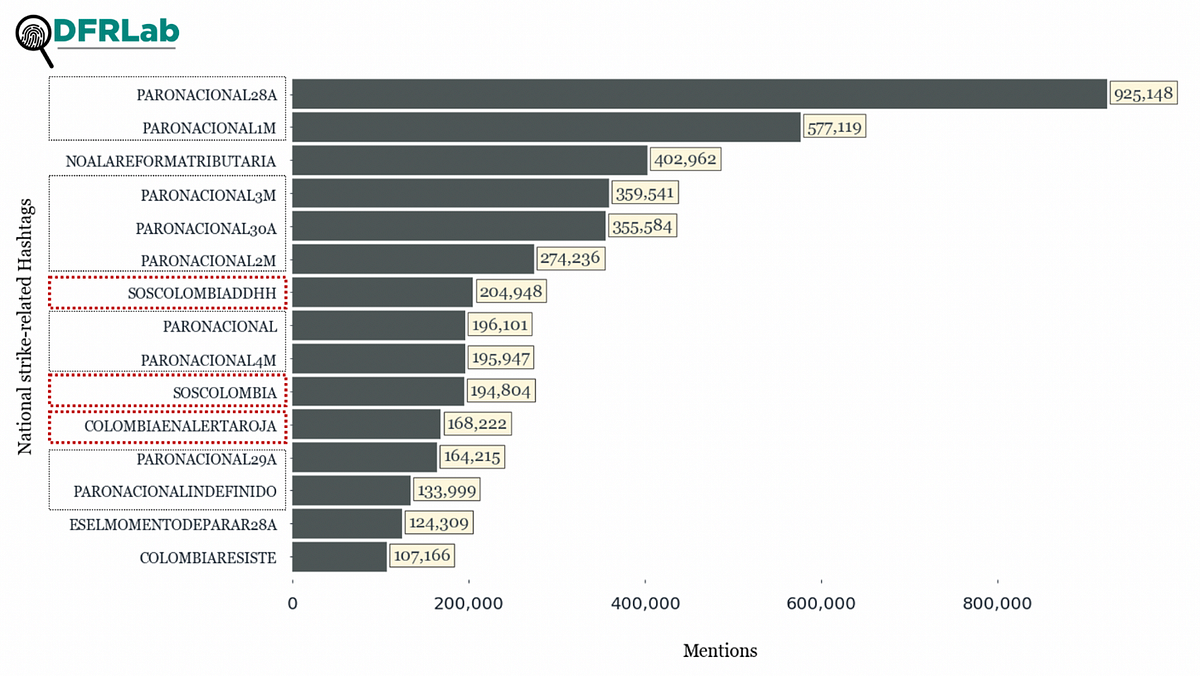

On Twitter, protest-related hashtags such as #ParoNacional28A (“National Strike April 28”) and #ParoNacional1M (“National Strike May 1”) have trended every day in Colombia since April 28. Using the social media listening tool Meltwater Explore, the DFRLab analyzed the volume of mentions of these hashtags. As of May 4, nearly three million tweets have been posted by roughly 450,000 accounts.

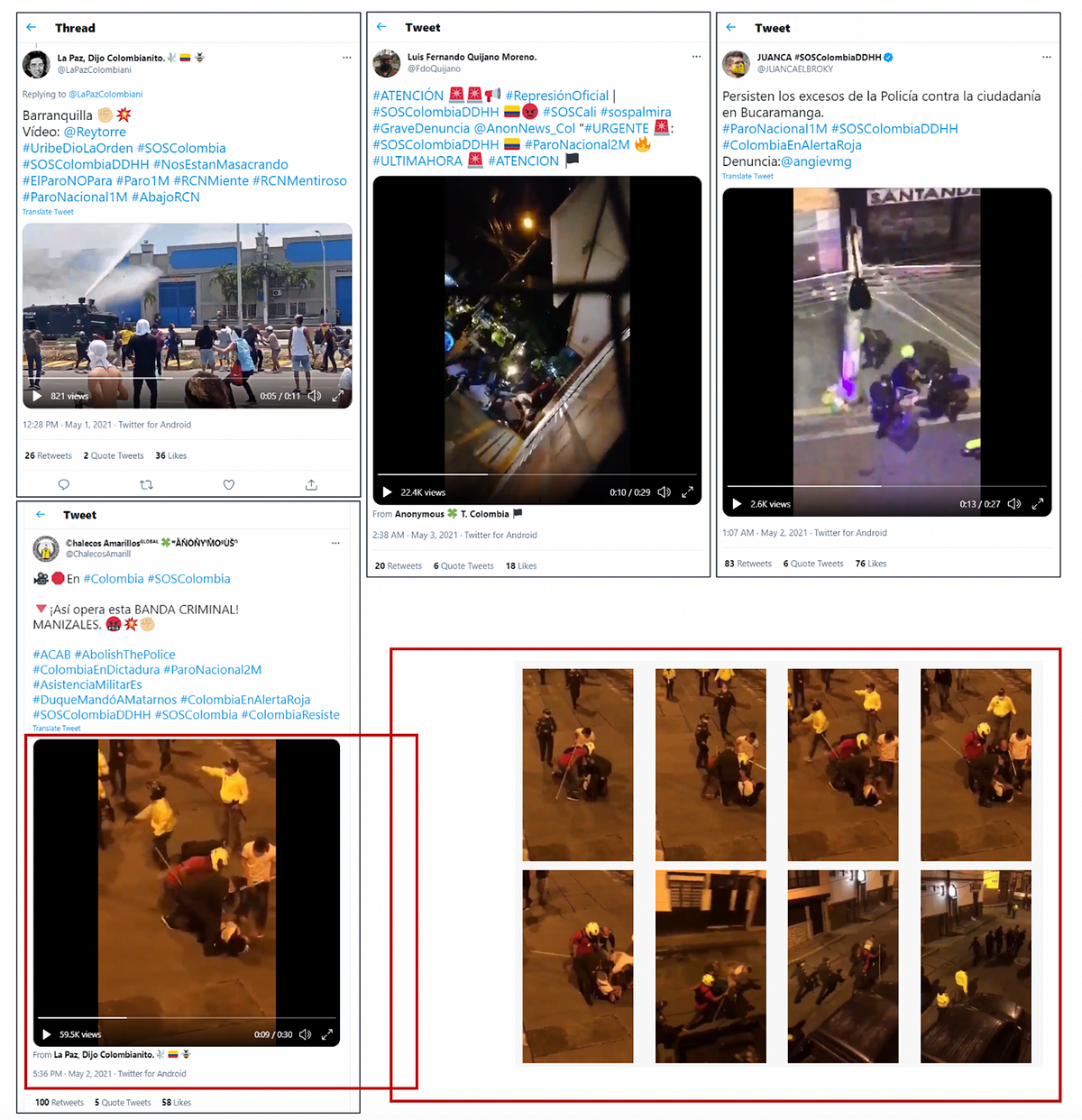

These hashtags were accompanied by additional tags, such as #SOSColombiaDDHH (“SOS Colombia Human Rights”), #SOSColombia, and #ColombiaEnAlertaRoja (“Colombia on red alert”). The content of these tweets often included narratives or videos highlighting excessive force by police.

Although conversations around the national strike have been circulating primarily on Twitter, social media accounts have used other social media platforms, including TikTok and Instagram, to upload content around the protests.

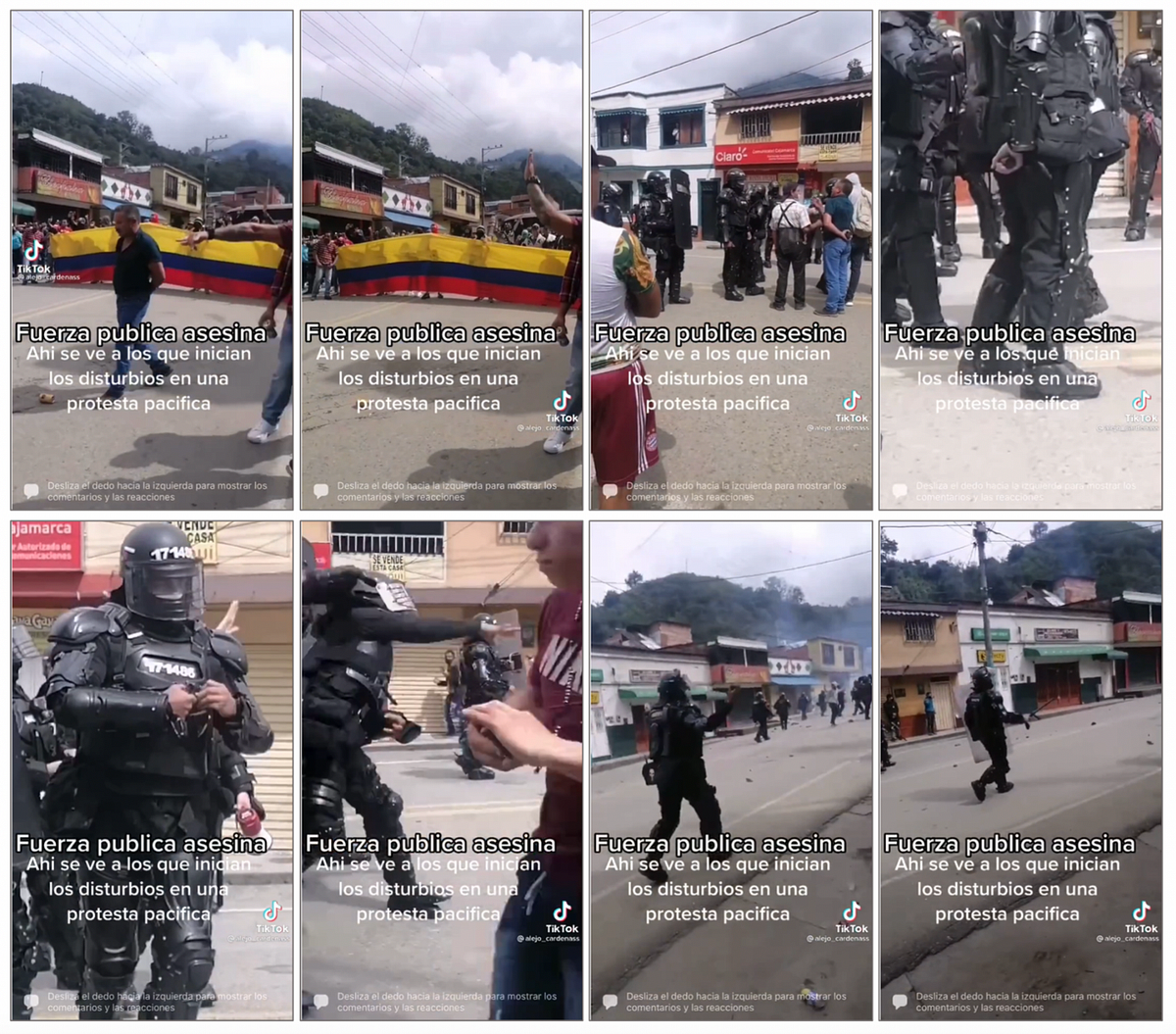

For example, the following image shows freeze frames of one widely circulated TikTok video in which protesters were confronted by ESMAD forces, who responded with tear gas. The video included text derisively describing the police force as “fuerza publica asesina” (“Deadly Public Force”). Initially, the video disappeared from the platform, but at the time of writing, it appears to have been restored. It has been favorited more than 148,000 times and shared more than 20,000 times.

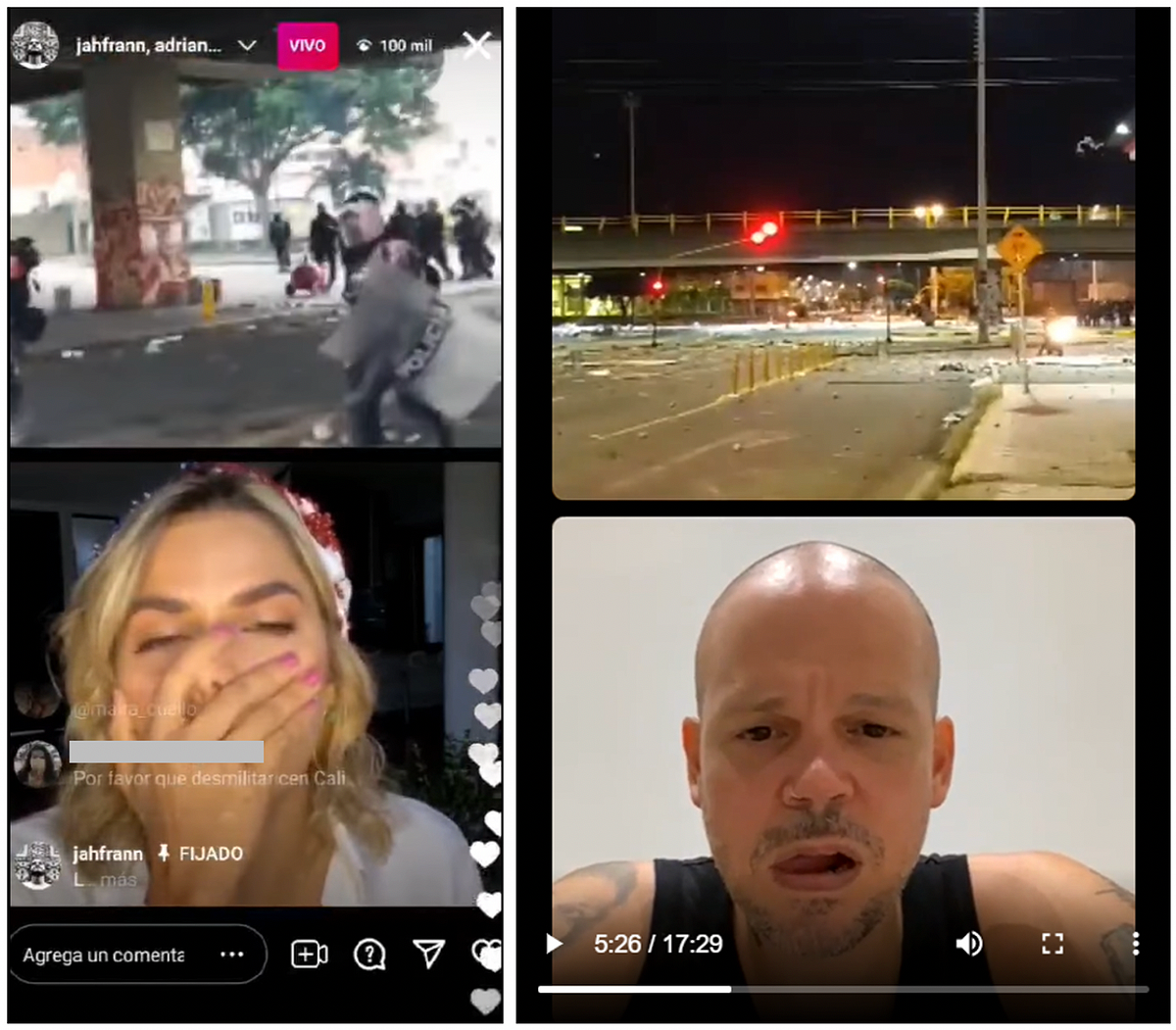

On Instagram, some users have streamed the protests using the platform’s Instagram TV feature. For instance, the user jahfrann, who identifies themselves as a member of the press, has streamed police abuses of power during the national strike in Cali. On May 3, Puerto Rican singer René Pérez Joglar, known as Residente, joined one of those streams to document the protests. The stream garnered more than 4 million views. Jahfrann also connected to Colombian singer Adriana Lucía during a livestream, reaching more than 100,000 viewers.

The DFRLab will continue monitoring the ongoing protests in Colombia, as strike organizers have announced that new demonstrations will take place in the coming days.

Daniel Suárez Pérez is a Research Assistant, Latin America, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Esteban Ponce de León is a Research Assistant, Latin America, with the Digital Forensic Research Lab.

Cite this case study:

Daniel Suárez Pérez and Esteban Ponce de León, “Misinformation about Colombia’s national strike spreads online and on air,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), May 7, 2021, https://medium.com/dfrlab/misinformation-about-colombias-national-strike-spreads-online-and-on-air-9c754666c06.

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from our #DigitalSherlocks.