Local support for Russia increased on Facebook before Burkina Faso military coup

Pro-Russian support increased in the Sahel, with residents of Burkina Faso holding Russian flags while celebrating recent coup.

Local support for Russia increased on Facebook before Burkina Faso military coup

Share this story

BANNER: People gather in support of a coup that ousted President Roch Kabore in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, January 25, 2022. (Source: Reuters/Anne Mimault)

Pro-Russian content spread on West African social media in the months ahead of the January 2022 military coup overthrowing the government of Burkina Faso. Online support for Moscow has steadily increased since then, including Facebook pages administered from the Sahel region dedicated to Russian Wagner Group mercenaries.

In September 2021, mentions of the Wagner Group by Facebook pages administered in Burkina Faso increased 19-fold, following claims the Russian private military contractor was headed to neighboring Mali. Although there did not appear to be any significant coordination among the Burkina Faso pages, as uncovered in our investigation of pages in Mali, the pages actively amplified false claims that Wagner soldiers were present in West Africa and promoted anti-French, pro-Russian narratives.

Support for Russia and demands for its intervention in the Sahel are not new. Protesters celebrating the coup told The New York Times they were inspired by Russia’s intervention in the Central African Republic (CAR) and Mali. However, traditional media in Burkina Faso were more skeptical of Russia’s involvement in the region, despite also showing a massive uptick in mentions of Wagner over the last few months.

Russian support in West Africa

On January 24, 2022, Burkina Faso’s state television station announced that the country’s military had deposed President Roche Kaboré in a coup, dissolved parliament, and suspended the constitution. Frustrations at the government’s inability to stem increasing violence from Islamist militants boiled over the day before the coup, as protesters ransacked the headquarters of Kaboré’s political party and soldiers demanded support in their fight against insurgents.

Burkina Faso’s new interim president, Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, had been appointed commander of the unit responsible for security in the capital in December 2021 after an attack by militants killed 49 officers and four civilians. Before taking power, Damiba allegedly attempted to persuade Kaboré twice to employ the Wagner Group, the Russian mercenary company that has assisted other African countries in fighting jihadists, according to The Daily Beast. Kaboré reportedly refused on both occasions.

Sahel countries, including Burkina Faso and neighboring Mali, have been wracked by spates of killings by Islamist extremists linked to al Qaeda and the Islamic State, both of which control large swathes of the region. French troops deployed in 2014 to fight the militants. Following the June 2021 coup in Mali, however, France announced it would start withdrawing from the region, culminating with French President Emmanuel Macron’s February 2022 announcement that French troops would withdraw from Mali. Anti-French sentiment has swept through West Africa, as citizens of the Sahel blame France, and the West more broadly, for failing to curb insurgencies in the region. Russia has increasingly been seen as an alternative option, particularly following the country’s perceived success at fighting militants in the CAR.

In a January 25 post to the Russian social network VKontakte (VK) via his company Concord Group, Russian oligarch and Wagner Group founder Yevgeny Prigozhin said the coup represented a “new epoch of decolonization” in Africa, stating that African states have been seeking freedom from Western rule and that he welcomed the military putsch in Burkina Faso. In a followup post on January 29, he wrote in French, “Vive une Afrique libre!” (“Long live Free Africa!”)

Meanwhile on Twitter, the account for the Community of Officers for International Security (COSI), a nongovernmental group representing Russian contractors in the CAR, also posted a statement from its director, Alexandre Ivanov. Ivanov was supportive of the coup and offered to train the Burkina Faso army using “experience acquired in CAR.” In 2021, a group of United Nations experts raised the alarm over the CAR government’s use of “Russian trainers” and their connections to a series of human rights violations.

Calls to hire the Wagner Group spread on Facebook prior to coup

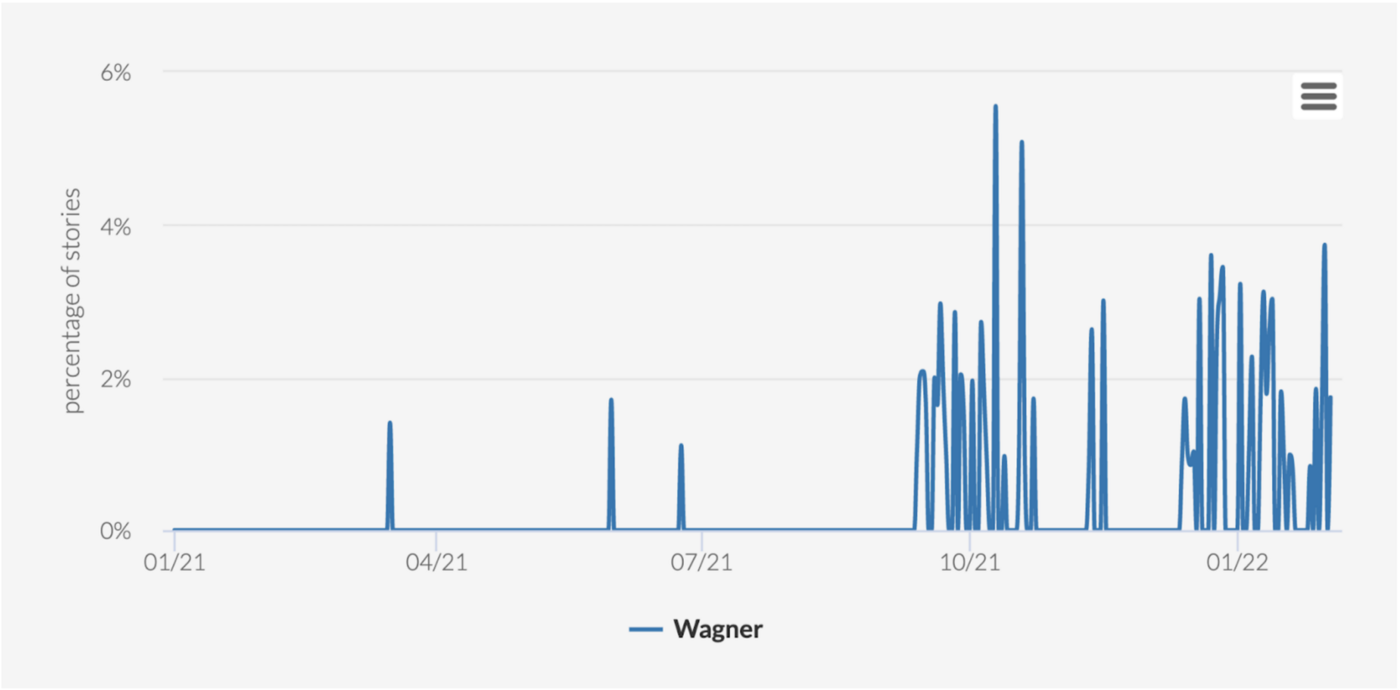

To better understand how the Wagner Group was being represented in Burkina Faso’s social media environment, the DFRLab and Code for Africa conducted a search across Facebook pages with administrators based in that country. According to this search query, conducted using the Facebook-owned research tool CrowdTangle, mentions of Wagner on Facebook pages administered from Burkina Faso spiked after September 13, 2021, when Reuters reported that Mali was in talks with the mercenary group.

Prior to the Reuters report, Wagner was rarely mentioned on Facebook pages administered in Burkina Faso. Between September 12, 2019 and September 12, 2021, Wagner was referenced just 66 times. These posts primarily commented positively on Wagner’s involvement in other African countries, including Libya and the CAR. In contrast, from September 12, 2021 until January 26, 2022, the same pages referenced Wagner 1,240 times, a 19-fold increase. Additionally, engagements on posts mentioning Wagner increased by 6,363 percent, from 5,500 to 350,000.

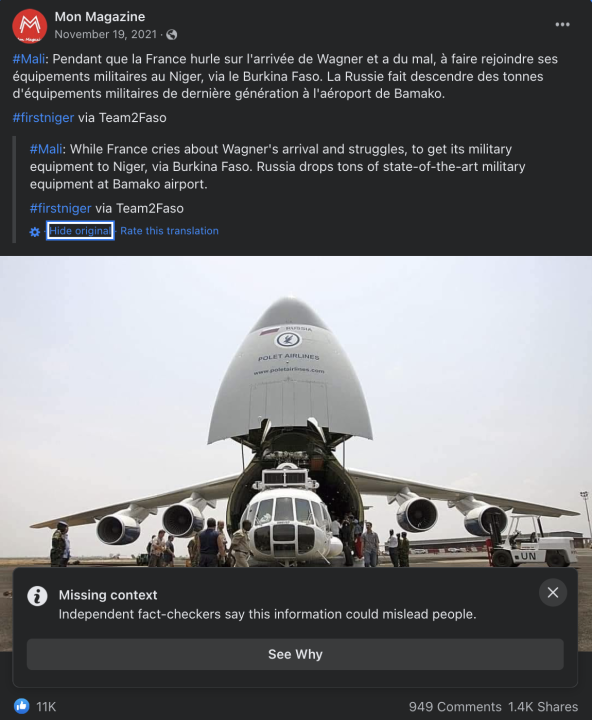

Posts about Wagner from September 12 onwards primarily focused on Russia’s support fighting insurgents in Mali. The post with the highest number of engagements criticized France for voicing concerns over a potential deal between Wagner and Malian leaders. However, the post was labeled as misleading by independent fact-checkers, as the image included with the post was taken in 2004, and did not show Russia delivering weapons to Mali.

Comments on the post were primarily supportive of Russian involvement in West and Central Africa, and called for Wagner to assist Burkina Faso in its fight against Islamist militants.

On September 16, as Wagner discussions began gaining traction in Burkina Faso, a pro-Wagner page named “Wagner Burkina Faso” appeared on Facebook, run by a single Burkina Faso-based administrator. At the time of writing, the page had grown to more than 26,000 followers. On its first day, the page published a post saying Wagner had arrived in Mali, reusing a 2019 image of Russian troops and armored vehicles in Syria. Since then, the page has consistently promoted Wagner, denigrated France, and called for Russian intervention in the Sahel.

Support for Russia and Wagner pre-dates the September 12 report of the alleged deal between Mali and Wagner, however. A page named “Défendons notre pays le Burkina Faso” (“Let’s defend our country Burkina Faso”) was created in February 2019, nearly two years before the coup, and started posting positive content about Russia as an ally of the Sahel soon after its creation. Its posts expressed support for Russia while criticizing France, calling for Burkina Faso to hire Wagner. At the time of publishing, the page had over 82,000 followers.

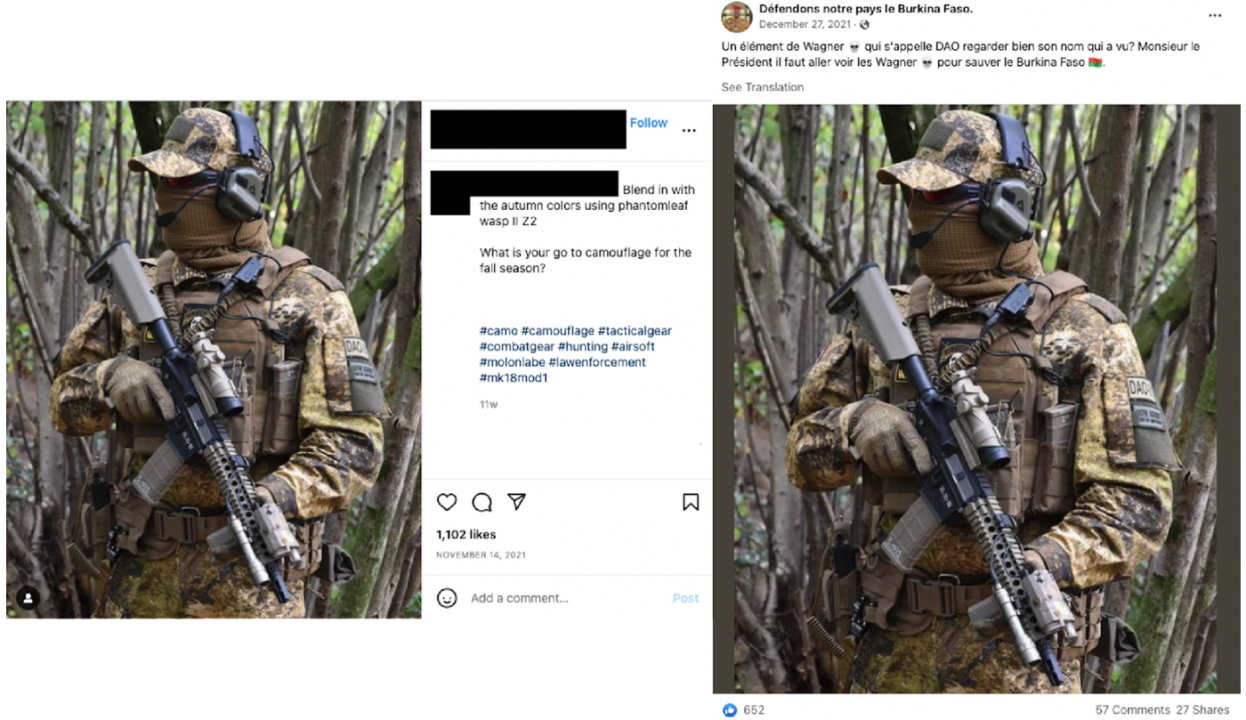

The page also repurposed images of Airsoft enthusiasts in camouflage from Instagram, claiming they were Russian soldiers. This technique was also used by other Burkina Faso-based pages that posted images of men holding Airsoft air rifles next to claims that France had failed the Sahel and Wagner would save the region from terrorists.

Copy/paste country crossover

Although there is evidence that mentions of Wagner from Burkina Faso-administered Facebook pages increased significantly following the Reuters report that Mali was on the cusp of making a deal with the company, this was not the only example of content crossover between the two countries.

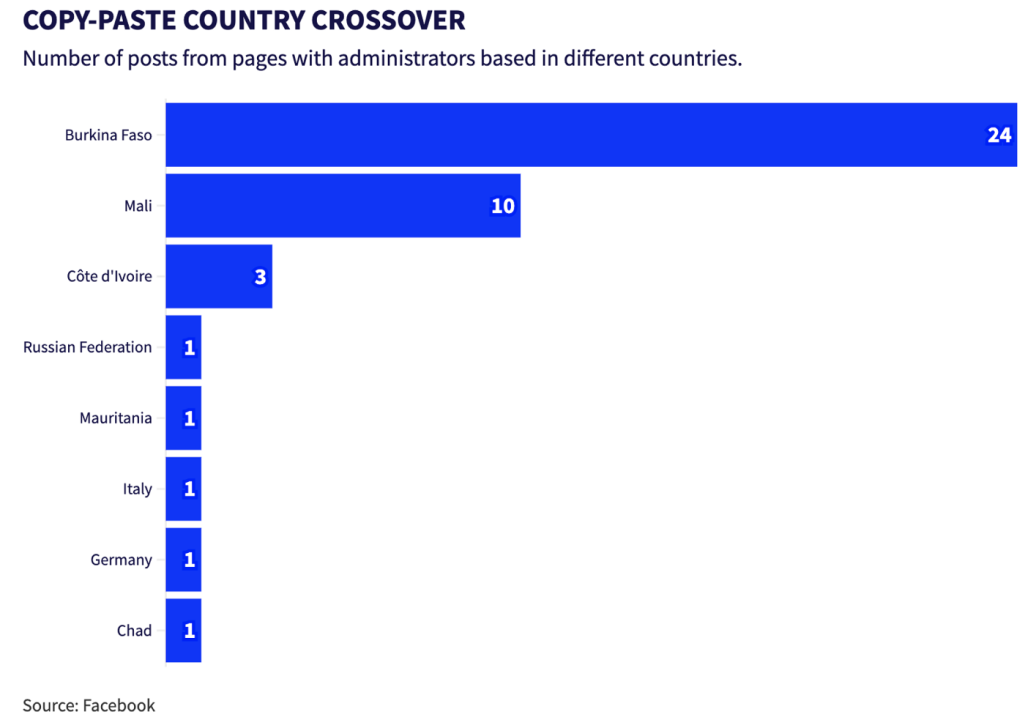

A post by the verified Facebook page for Burkinabe radio station Radio Omega regarding Ivanov’s offer to send Russian instructors to Burkina Faso was copied by at least 42 other pages, including 24 pages with administrators based in Burkina Faso. Some of the copied text included the hashtag #Omega, perhaps as a credit of sorts, while others simply copied the content without crediting Radio Omega. The copied text, sometimes accompanied by different images, was reposted by pages with administrators based in other West African countries, such as Mali and Chad, as well as diaspora communities in Europe. Although some pages copied and posted the content within minutes of Radio Omega’s original post, the DFRLab could not find evidence of coordination.

Traditional media amplification

Mentions of Wagner also increased in local Burkina Faso media outlets in parallel with social media. From January 1, 2021 until September 12, 2021, Wagner was mentioned four times by local media outlets, according to CivicSignal Media Cloud, a media monitoring platform that tracks African media mentions, including 23 outlets in Burkina. From September 12, 2021 to February 3, 2022, Wagner was mentioned in 93 articles, an increase of 2,325 percent from the previous period.

However, unlike the narratives seen on social media, some of the narratives spread by traditional media were more critical of Wagner and Russia’s presence in the Sahel. A recent editorial by the news site Aujourd’hui au Faso (“Today in Faso”) commented on the risk of Wagner filling the vacuum that will be left by France.

Despite criticism in traditional media, support for Russia and calls for Wagner to support Burkina Faso — and the broader Sahel region — continue to grow on social media. The presence of Russian flags at celebrations and demonstrations held the day after the military took control of the government of Burkina Faso shows how pro-Russian influence, often proliferated online, impacts real-word perceptions of the country.

Cite this case study:

Tessa Knight and Allan Cheboi, “Local support for Russia increased on Facebook before Burkina Faso military coup,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), February 17, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/local-support-for-russia-increased-on-facebook-before-burkina-faso-military-coup-a51df6722e59.