Divisive ad campaign targets candidates ahead of Colombian presidential primary

Two Facebook pages promoted paid campaigns sharing homophobic, manipulated, and false content.

Divisive ad campaign targets candidates ahead of Colombian presidential primary

Share this story

BANNER: Presidential hopeful Gustavo Petro (center) at a presidential debate in Bogota, January 27, 2022. Petro was targeted in the Facebook Ads campaign. (Source: Reuters Connect/Sebastian Barros/NurPhoto)

Ahead of Colombia’s 2022 presidential elections, hyper-political Facebook pages pretending to be neutral platforms paid for ads across Meta platforms to attack a wide spectrum of political leaders, ranging from left-wing presidential hopeful Gustavo Petro to right-wing former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe.

The pages Micolombia (“My Colombia”) and Colombia LIBRE (“Free Colombia”) spent the equivalent of nearly USD $48,000 on ads related to politics or elections between December 30, 2021 and January 28, 2022 — more than any other organization or presidential campaign in Colombia in the same period.

The advertising campaign has amplified homophobic, hateful, manipulated, and false content, exacerbating social and political polarization in the run-up to Colombia’s elections. In doing so, the campaigns may have potentially violated Meta’s branded content policy and community guidelines on hate speech. On February 9, 2022, Colombia LIBRE’s Facebook page went offline — it remains unknown whether the removal was through administrator or Meta action — while its Instagram account used to distribute the ads remained active.

The pages have not publicly shown support for a particular presidential candidate, and the DFRLab was not able to connect the campaign to any candidate. There are, however, clear links between the campaigns and marketing agencies Cdigital SAS and Marketing Digital Strategy, indicating that “disinformation for hire” might be a challenge in Colombia’s general election.

Disinformation and misinformation were pervasive on social media platforms during the previous presidential elections in Colombia in 2018, as well as during the country’s peace deal referendum in 2016. The social unrest against current President Iván Duque’s government that began in April 2021 also triggered public debate around the presidential elections much earlier than is normal, creating a more volatile political environment well ahead of any electoral activity.

The divisive political ads preceded two important deadlines for the selection of presidential candidates. Candidates intending to run independently without coalition support need to submit their registration to Colombia’s electoral authorities by March 11, 2022,. On March 13, the coalitions will hold primary elections, known locally as inter-party consultations. Prior to the consultations, each potential selection is referred to as a “pre-candidate.” The first round of the presidential election itself will be held on May 29, 2022. If no candidate is elected with more than 50 percent of the vote, a runoff between the two candidates with the most votes will be held on June 19.

Ads exploiting ruptures

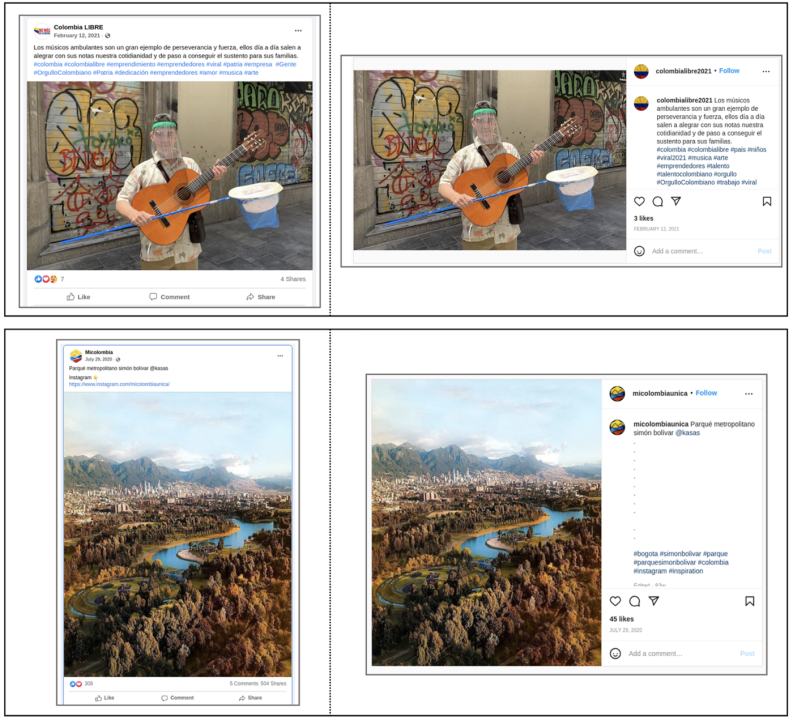

The Facebook pages used ads to amplify their political narratives while creating a distinct façade of organic posting behavior. Colombia LIBRE’s Facebook page and affiliated Instagram account, for instance, posted photos of local entrepreneurs and memes about entrepreneurship, while Micolombia posted mostly photos of Colombian travel destinations.

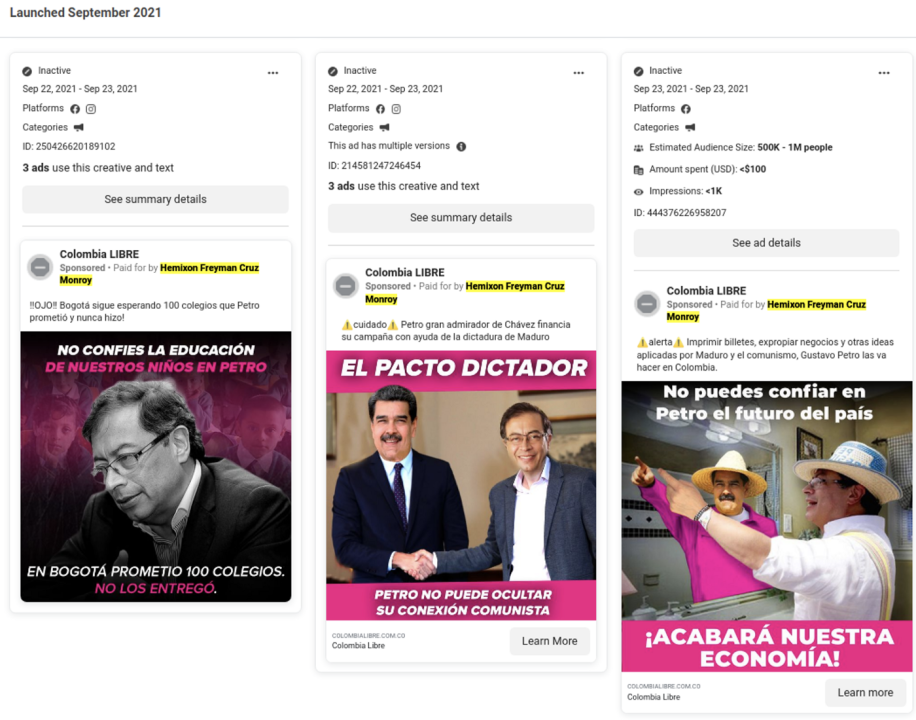

According to a query of Colombia LIBRE’s ad library, the page posted its first ad campaign on September 8, 2021, and had published 670 ads as of February 7, 2022. The total cost for these ads was more than 191,600,000 Colombian pesos (nearly USD $48,500). Meanwhile, Micolombia spent over 106,500,000 Colombian pesos (nearly USD $27,000) on twenty-four ads posted between January 20 and February 7, 2022.

Colombia LIBRE and Micolombia’s campaign appeared to change focus according to what was happening in the run-up to the March 13 candidate selection. Colombia LIBRE started paid campaigns on September 8, 2021, targeting only Gustavo Petro, which suggested the campaign was coming from political opponents. Petro, a left-wing candidate, is currently leading the polls.

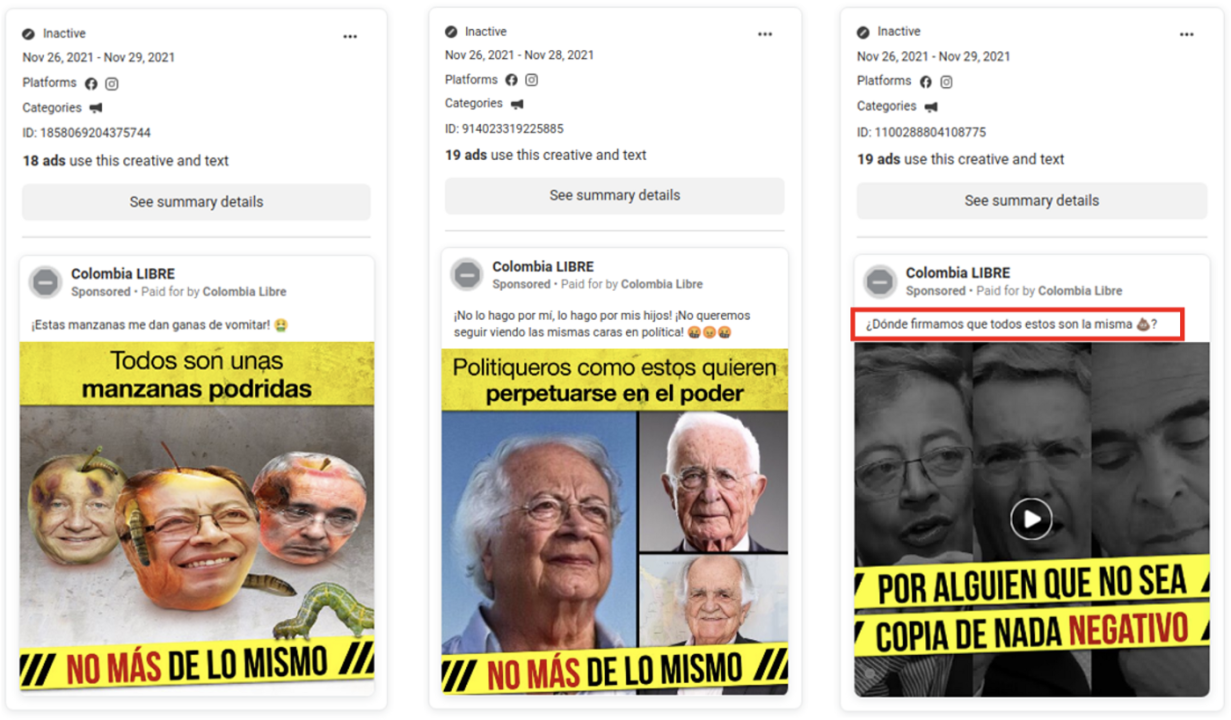

After the Centro Democrático (CD) party nominated Óscar Iván Zuluaga as its candidate on November 26, precluding any participation in the consultations alongside other right-wing parties that previously supported CD, there was a change of direction. Around the same time, the right-wing coalition Equipo por Colombia indicated it was experiencing internal divisions.

The page then ran new ads criticizing CD leader Álvaro Uribe and pre-candidates including Zuluaga, but also pre-candidates from other political ideologies, including centrist Sergio Fajardo and independent Rodolfo Hernández. The ads’ change of political targeting may have been a result of internal divisions on the right.

Later on December 3, the Colombia LIBRE ad campaign renewed its focus on Petro and Uribe. MiColombia began doing the same on January 20, 2022.

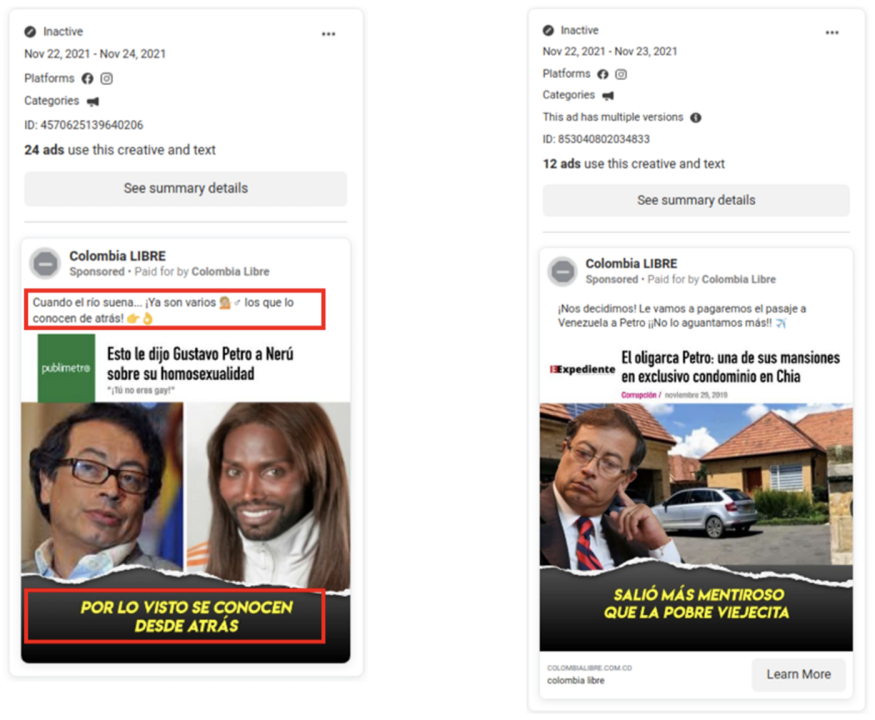

Colombia LIBRE’s ads against Petro contained memes and videos that amplified highly dubious and exaggerated narratives promoted by right-wing leaders, such as a claim that Petro would lead Colombia to a dire situation similar to Venezuela’s chavismo ideology if he were elected president.

Colombia LIBRE also pushed misleading claims about Petro based on headlines from partisan websites such as the pro-Uribe El Expediente, which previously promoted a right-wing agenda during the 2018 presidential elections. The ads did not tag any of the media outlets, and there was no indication that the outlets had any knowledge that their content was being used in the ads.

At least one of the ads featured homophobic content. Such hyperbolic attacks may resonate in Colombia, which still struggles with problems of violence targeting the LGBT community.

The ads targeting Petro and other political leaders primarily used memes and videos to discredit them. For instance, one used a meme showing pictures of the faces of Petro, Uribe, and Hernandez to describe them as rotten apples. The post’s text contemptuously read, “These apples make me vomit.”

A coordinated effort

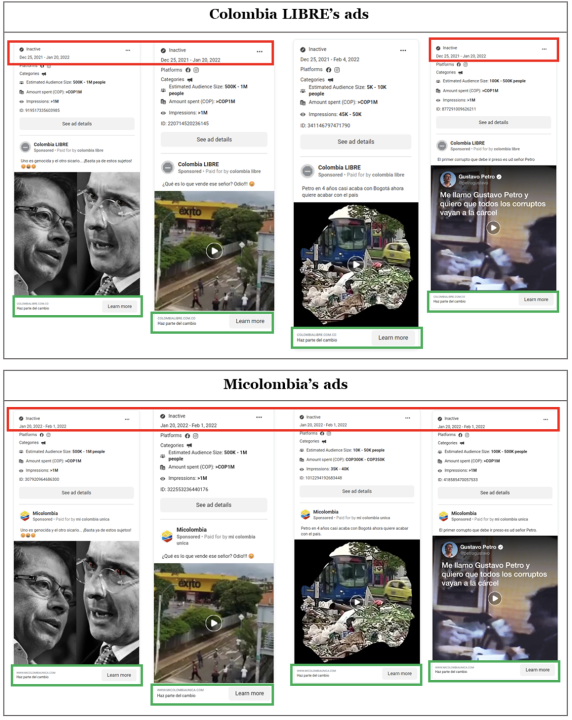

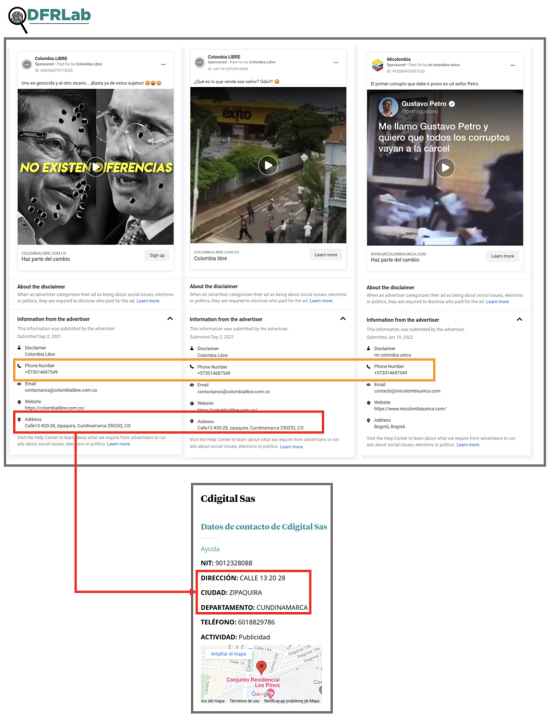

Colombia LIBRE’s and MiColombia’s ad campaigns were coordinated, as their advertisers shared the same contact information. And after January 20, Micolombia’s paid campaigns also began to use content from Colombia LIBRE’s earlier ads.

Of the sixteen ads placed by each page, four of them contained videos and accompanying text overlapping each other, using the same calls to action.

The ads also garnered user reactions that highlighted their dubious nature. Between December 2021 and January 2022, Facebook users posted negative comments about the ads in the recommendations and reviews section of Colombia LIBRE’s Facebook page. Colombia LIBRE apparently was deleted — either by the operator or by Facebook— at some point in the first week of February 2022; this disappearance followed Facebook users and other internet reporters denouncing the content of the ads in public posts on Facebook and Twitter.

Marketing firm connections

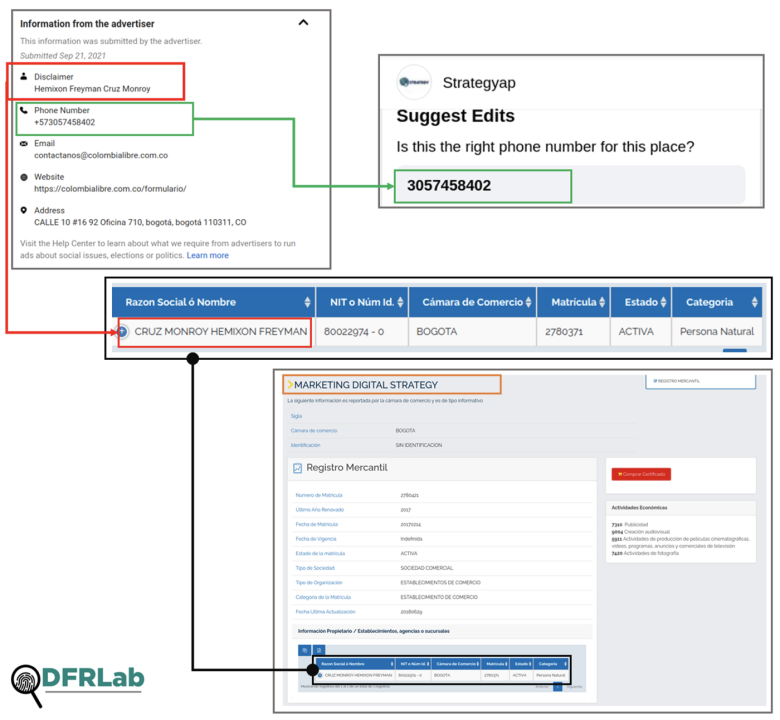

The information from the advertisers available on Meta’s Ad Library Report showed connections with two marketing firms: Cdigital SAS and Marketing Digital Strategy.

The advertiser behind twenty-two anti-Petro ads posted by Colombia LIBRE on September 23 and 24, 2021, was an individual by the name of Hemixon Freyman Cruz Monroy.

A search of Registro Único Empresarial y Social (RUES), Colombia’s business registry database, showed that Cruz is the legal representative of marketing firm Marketing Digital Strategy. On Facebook, Marketing Digital Strategy has a page named Strategyap. This page has changed names eleven times since its creation. The latest change happened on January 21, 2022, after Camilo Andrés García, whose Twitter account declares that he is a “Christian, journalist, and neo-communist,” posted a thread and a blog in which he revealed he contacted Cruz, impersonating a client. García said Cruz told him he was working for a presidential campaign but did not reveal the name of the candidate.

Strategyap has the same phone number and location that appears on Colombia LIBRE’s Ads Library.

Contact information on the disclaimers for Colombia LIBRE and Micolombia also linked the two pages with Cdigital SAS, a marketing firm located in Zipaquirá, a city close to Bogotá.

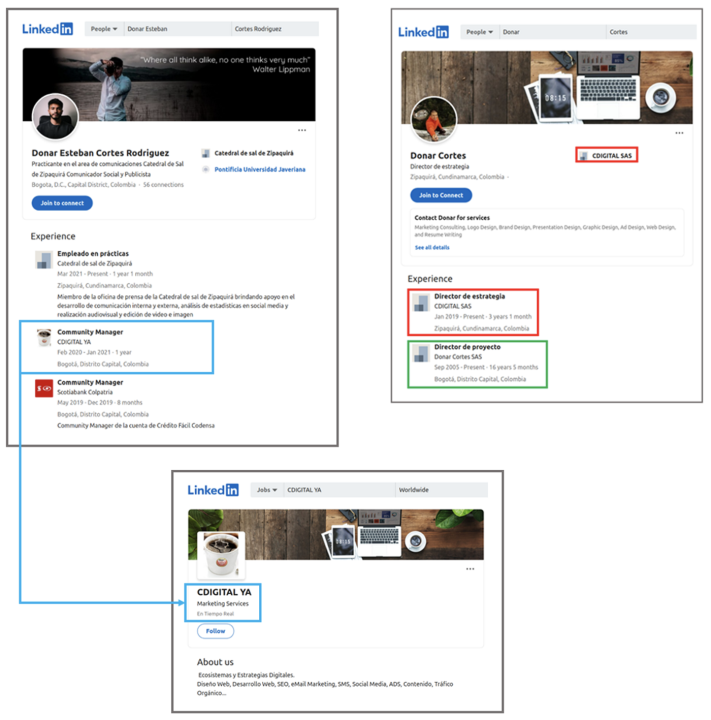

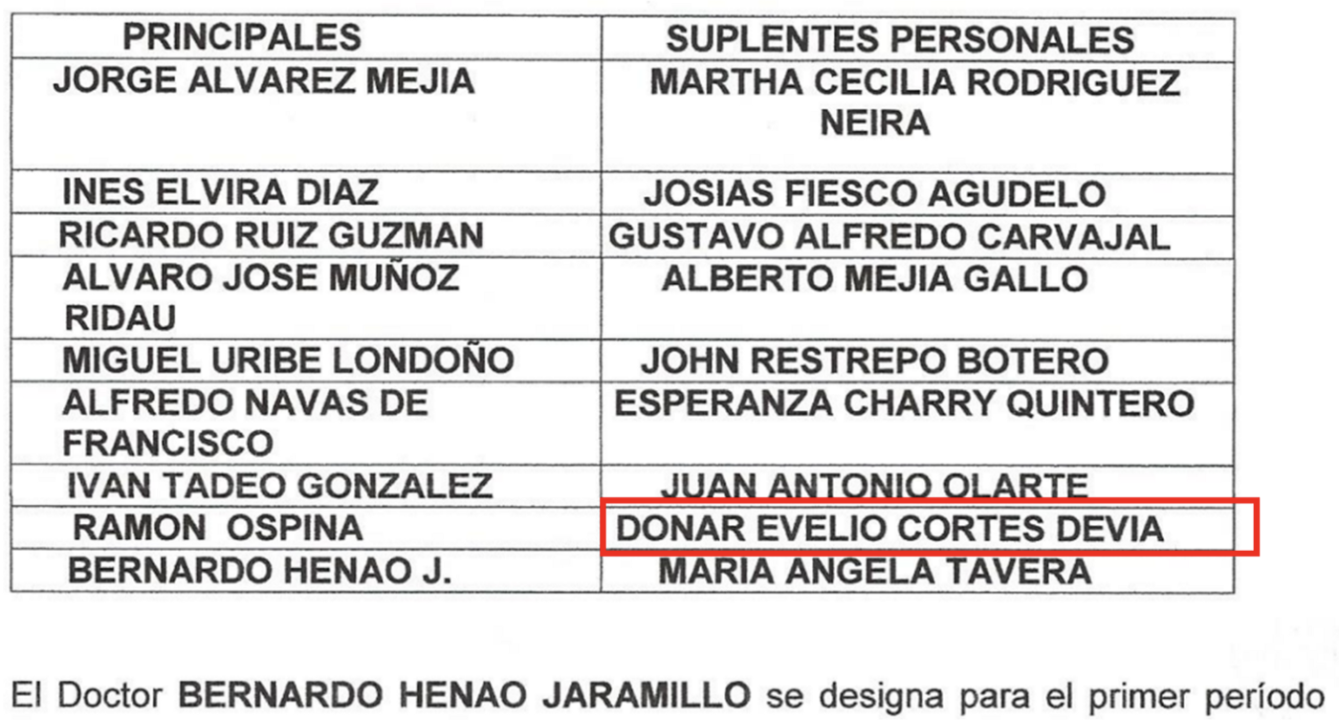

RUES information shows that Donar Esteban Cortes Rodriguez is the legal representative of Cdigital SAS. The registration is still active, most recently updated on September 27, 2021.

A search on LinkedIn and Facebook showed that Donar “Esteban” Cortes Rodriguez and his father, Donar Evelio Cortes Devia, are behind Cdigital SAS operations.

Meanwhile, a Facebook user account for “Donar Cortes” likes the Micolombia Facebook page.

Donar Evelio Cortes appears to have links with politicians from different political parties: he has appeared on Facebook interviewing Gloria Isabel Ramírez Rios, Colombia’s Ambassador to Italy and former communications advisor to Duque and Uribe’s presidential campaigns . He has also posted photos supporting Wilson Garcia Fajardo’s successful 2019 campaign for mayor of Zipaquirá. García belongs to Alianza Verde, a party aligned to the center coalition and opposed to Duque’s government.

Donar Evelio Cortes is also a founding member of the association Únete por Colombia, a think tank that describes itself as “protecting Colombia’s institutions and democracy.”

At least one person on the Únete por Colombia list has previously been involved in inauthentic operations to influence the social media conversation in favor of Centro Democrático. David Ghitis, an Uribe supporter, is reported to be a member of “bodeguita uribista,” an inauthentic network exposed in February 2020 for manipulating social media networks and pressuring journalists. Bodeguita uribista amplified pro-Duque and pro-Uribe narratives, and included Duque government officials among its members.

Despite these political links, the DFRLab cannot confirm if Donar Evelio Cortes was acting on behalf of any campaign, political parties, or associations.

Conclusion

The timing of the advertising attacks against Uribe and Zuluaga suggested that the campaign might be related to the divisions Centro Democrático had internally among its pre-candidates and with other right-wing parties that supported Centro Democrático’s candidate in the 2018 presidential elections, such as those in the Equipo por Colombia coalition.

The involvement of marketing firms sheds light on the practice of “disinformation for hire” in Colombia, and it remains to be seen whether negative campaigns produced by private companies will become an important characteristic of this year’s general election. If the marketing firms were hired by political actors, they should appear in candidate’s and party’s electoral spending reports, meaning it is possible that the people behind this campaign will be known in the future.

Cite this case study:

Daniel Suárez Pérez, “Divisive ad campaign targets candidates ahead of Colombian presidential primary,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), March 10, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/divisive-ad-campaign-targets-candidates-ahead-of-colombian-presidential-primary-108f4281b50c.