Russia’s domestic internet talk isn’t new – but it’s ramping up

The size and scope of the ongoing crackdown is unprecedented.

Russia’s domestic internet talk isn’t new – but it’s ramping up

Share this story

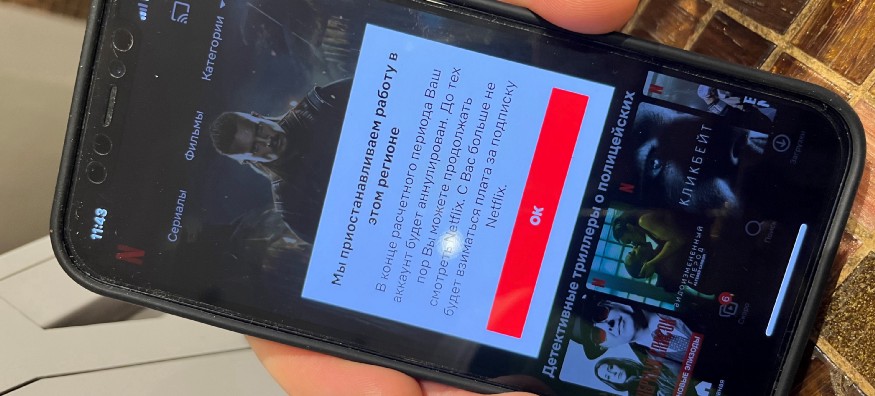

BANNER: A young Russian man who has a Netflix subscription shows his cell phone with an ad: “We suspend work in their region.” According to the statement, the service can still be used until the end of the billing period. After that, the user account will be deleted, there will be more debits, the information says. (Source: DPA/Picture Alliance via Reuters)

The Russian government has in recent days accelerated its unprecedented crackdown on the internet and on foreign technology platforms within its borders.

While much of the media coverage has focused on the banning or blocking of Facebook, Twitter, BBC News, Deutsche Welle, and other platforms and websites, the recent Russian moves go far beyond a one-off focus on foreign companies. On March 6, Russia’s Ministry of Digital Development instructed all state websites and services to switch to a Russian domain name system by March 11. (The DNS is like the internet’s “phone book” for traffic, converting website names like atlanticcouncil.org into machine-readable numerical IP addresses.) The Ministry also instructed state websites and services to stop using foreign hosting services, cease the use of foreign website traffic counters, and strengthen their password policies to protect from, paraphrasing the state’s words, the possibility of foreign-forced internet disconnection as well as cyber attacks.

None of this rhetoric is new. For years, the Kremlin has discussed creating a domestic Russian internet, routinely referring to the global internet as a foreign project and a threat to regime security, out of the paranoid belief that foreign technology platforms and the internet writ large are little more than a Western project to topple unfriendly regimes. In 2019, the Russian government formalized its intentions: it passed a new law calling for a domestic Russian internet that could be isolated in the event of a state-identified security incident. (For the Russian government, a security incident would include individuals spreading truths that reflect badly on Vladimir Putin and his inner circle.)

Moscow has faced numerous stumbling blocks in pushing for a domestic internet that it can (at least relatively) isolate from the global one at will. Doing so would require the ability to filter traffic flows into and out of Russia, the ability to move website content to domestic servers, and the ability to centralize state control of a very diffuse, complex Russian internet architecture, among other requirements. The Russian government called for the creation of a domestic alternative to the DNS as early as 2017 but has made little progress in the intervening years. Traffic filtering has also been a challenge, as evinced by a multi-year failure to block access to Telegram. The Kremlin had more success throttling access to Twitter in 2021, when the company refused to comply with censorship demands related to the Navalny protests, though that also resulted in multiple other websites accidentally becoming unavailable. It is unclear whether the state has greatly expanded and improved its traffic filtering capabilities since.

The Russian government has also faced political challenges in advancing the push for a domestic internet, and this is where Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recent, aggressive clampdown really comes into play. In recent years, a lack of political prioritization meant smaller technical pieces of the domestic internet puzzle weren’t put into place.

For instance, Russian internet companies weren’t pushed to and didn’t prioritize installing deep packet inspection (DPI) equipment on their networks. (DPI equipment would allow the state to examine and control internet traffic beyond just basic IP and other packet header information.) Even though Roskomnadzor, Russia’s internet and media regulator, was reportedly buying the DPI equipment required, companies would be forced to power and service it once installed on their networks — likely another disincentive for moving quickly. Foreign companies, including US social media platforms, have also largely ignored Russia’s data localization requirements and merely paid small fines without serious consequences.

The Kremlin’s growing political pressure on technology companies could shift this calculus. Where Russian government authorities were not significantly pushed and/or empowered to accelerate plans for this “domestic internet,” they could be in the coming weeks and months. That might look like greater political pressure on Russian internet providers to install filtering equipment, more public statements from the Kremlin (which do matter) about the need for a domestic internet, and more money to Roskomnadzor and other entities working on centralizing state control of internet architecture. Unlike the Chinese government’s internet control model, which is heavily technical and very sophisticated, the Russian government’s internet control model leans on more limited filtering paired with traditional, physical coercion — like requiring companies to open local offices enabling the state to pressure and threaten staff.

At the same time, policymakers must remember that Russia’s recent rhetoric fits into a longer history. The Kremlin may talk a good game about the domestic internet idea, but implementing that vision is a completely different equation. Moscow’s internet clampdown — alongside unprecedented actions against foreign internet platforms — is only poised to get worse over the coming weeks. This will hurt Russians domestically, as Russian citizens in the coming weeks and months will have even fewer options to share and access information freely. These restrictions will also reverberate globally, as the world debates whether the idea of a free, open, secure, and interoperable global internet can sustain while countries like China and Russia push for these “sovereign” digital spheres. As aspiration becomes reality, that debate becomes more acute. As the Putin regime catalyzes a serious economic and technological fracturing between Russia and the West, the underlying motives, political questions, and technological challenges are still in play.

Justin Sherman is a fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative.

Cite this case study:

Justin Sherman, “Russia’s domestic internet talk isn’t new — but it’s ramping up,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), March 11, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/russias-domestic-internet-talk-isn-t-new-but-it-s-ramping-up-a1fe8c24779.