Suspicious Twitter accounts artificially amplify Sudanese paramilitary leader amid armed conflict

Network of accounts routinely copy-pastes content to promote pro-RSF narratives and its leader, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo

Suspicious Twitter accounts artificially amplify Sudanese paramilitary leader amid armed conflict

Share this story

Rapid Support Forces leader General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo speaks during a press conference at RSF headquarters in Khartoum, February 19, 2023. (Source: Reuters/Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah//File Photo)

A network of Twitter accounts is promoting the leader of Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti, by posting copied content and duplicate replies. Tensions between Hemedti and military chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan escalated to the point of armed conflict on April 15, 2023, with more than 200 civilians dead at the time of writing. The DFRLab also identified a separate Twitter network promoting the RSF and Hemedti, which we covered in a previous case study. With the latest instance, the network’s content appears to fall into three categories: tweets copied directly from the official Twitter accounts of the RSF or Hemedti; posts promoting Hemedti and the RSF; and replies to tweets posted by the RSF and Hemedti.

Prior to the armed conflict between the RSF and al-Burhan’s Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), the accounts portrayed Hemedti as a reformist general who supports the move toward democracy, a competent leader of a powerful paramilitary force, and a viable future leader for Sudan. After fighting began on April 15, the accounts portrayed Hemedti as a hero fighting to protect Sudan and cleanse the country of traitors.

Often the accounts posted the same content within seconds and minutes of one another. Replies to tweets, which were often identical or incredibly similar, mostly praised and thanked both Hemedti and the RSF.

As previously noted, the DFRLab also examined a network of potentially hijacked accounts used to promote the RSF, which utilized accounts that had been dormant for years. This latest network differs in that the accounts appear to be new. The majority of accounts were created in late 2022, around the same time Hemedti claimed the 2021 military coup, which overthrew the transitional government, was a failure.

These instances are not the first time the DFRLab has reported on suspicious tactics used to promote the RSF. In October 2021, Facebook parent company Meta de-platformed a network promoting the RSF and Hemedti for “coordinated inauthentic behavior on behalf of a foreign or government entity.” The network included page administrators based in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, both of which have long-standing relationships with the RSF.

Some high-engagement accounts that formed a significant part of the latest network identified by the DFRLab were previously investigated by Beam Reports, a Sudanese media outlet focused on fact-checking and disinformation investigations. Beam Reports has documented other examples of potentially fake or inauthentic accounts used to promote the RSF on multiple social media platforms.

Methodology

To identify the suspicious accounts promoting Hemedti and the RSF, the DFRLab used a dataset initially created to classify a potentially hijacked network of Twitter accounts that boosted content posted by the official accounts of the RSF and Hemedti. The dataset contained 4,882 accounts that liked at least one tweet from either of the official accounts. As noted in our prior report, we observed some inconsistencies between the data publicly visible on Twitter’s website and the data collected via API. For example, in a number of cases, Twitter’s website would show that particular account had liked a tweet by the RSF, but this was not reflected in the collected API data. As a result of these current inconsistencies between Twitter’s website and API, it is likely that the total number of accounts we identified is an undercount.

For this research, the DFRLab focused on the most engaged accounts that liked, replied to, and shared tweets by Hemedti and the RSF, in addition to posting copied and original promotional content. The high engagers appeared to primarily like and retweet content from the official RSF account rather than Hemedti’s account. However, the accounts mentioned Hemedti in their own tweets or in replies to Hemedti’s tweets. Most of their original tweets promoted Hemedti as an individual leader rather than the RSF as a paramilitary group.

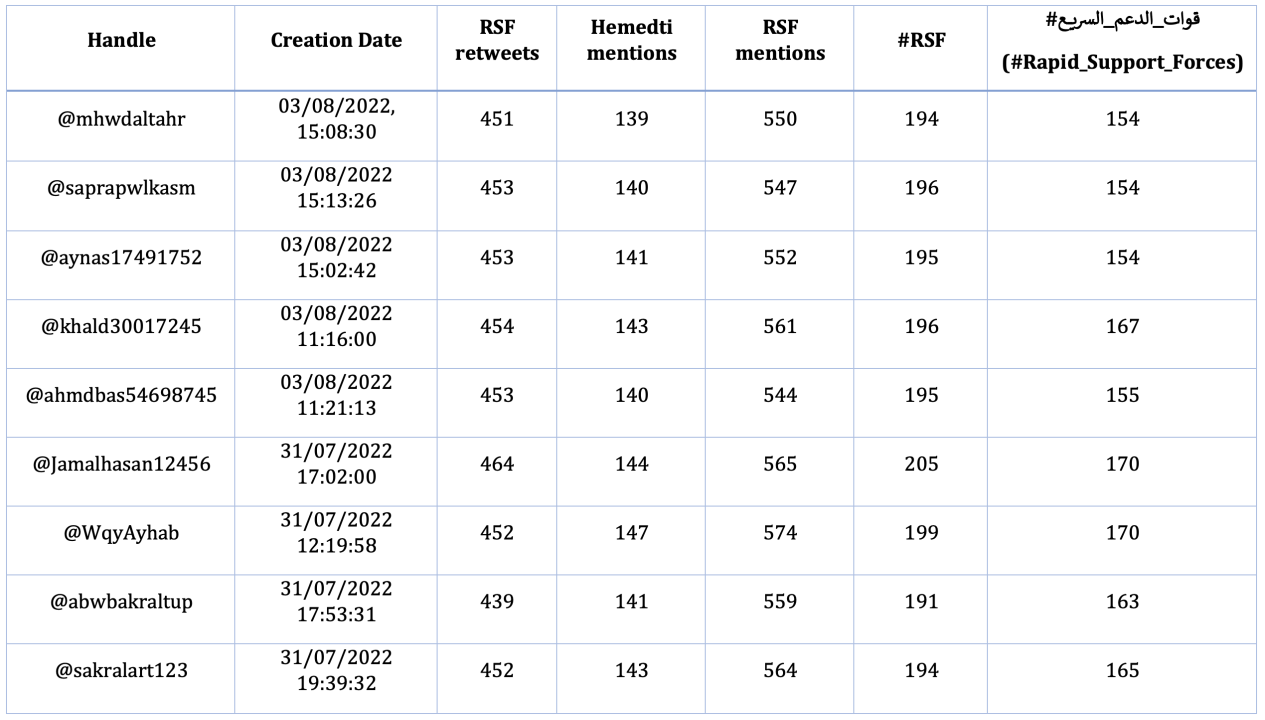

The majority of accounts the DFRLab identified as part of this copy-paste network appear to have been created between July and October 2022, with many created on the same day. For example, three high engagers were created on August 3, 2022, within thirteen minutes of one another. At least nine highly-engaged accounts consistently interacted with the accounts of the RSF and Hemedti in a similar fashion, including mentions, retweets, and the use of specific hashtags, like #قوات_الدعم_السريع (#Rapid_Support_Forces).

Copying promotional content

Many of the accounts copied content directly from the Facebook pages and Twitter accounts of Hemedti and the RSF, sharing it as if it were their own content.

On April 17, ten accounts shared a shortened version of a video originally posted by the RSF hours earlier. The accounts cropped the video, which alleged to show RSF members taking control of Merowe airport, to highlight RSF soldiers celebrating in front of a banner with the airport’s name. The RSF originally surrounded Merowe airport on April 12, resulting in the SAF issuing a warning that the move could result in conflict. The accounts shared the video between 3:20pm and 3:30pm Central Africa Time, each posting in one-minute intervals.

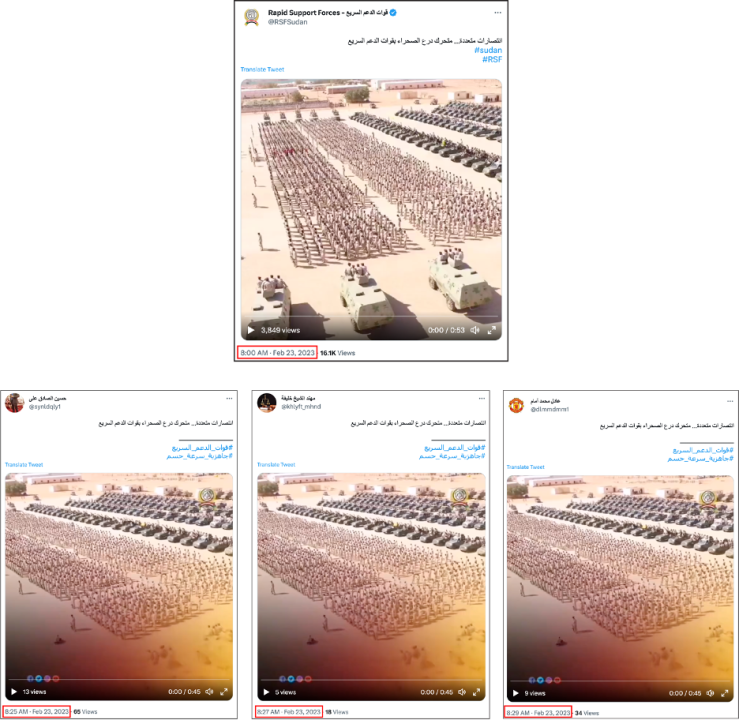

In a similar example, eighteen accounts copied a video and text from an RSF tweet posted on February 23. The accounts, which all posted their content within three hours of the original RSF post, used a cropped version of the video that removed the first eight seconds of footage. The eighteen accounts copied the RSF’s Arabic text, which translated to “Multiple victories… Mobile Desert Shield Rapid Support Forces.” While the RSF used the hashtags #sudan and #RSF, the eighteen copypasta accounts used the hashtagsقوات_الدعم_السريع # (“Rapid_Support_Forces”) and #جاهزية_سرعة_حسم (Accessibility_Rapidity_Resolvedly).

Original promotional content

Almost all of the identified accounts posted some form of original content that was not copied directly from the official Twitter accounts of Hemedti or the RSF. These tweets consisted of content promoting the RSF and Hemedti or summaries of content from their Twitter accounts.

On April 16, ten accounts posted an image of Hemedti saluting troops, with a message praising him as a leader who will cleanse Sudan of “traitors and hypocritical revolutionaries.” The accounts posted the image and text within six minutes of one another.

The accounts in this network regularly tweeted headlines that included positive news about the RSF and Hemedti, or articles that situated Hemedti as a potential ruler. For example, on April 10, twenty-four accounts tweeted a post copied from the official account of Saudi outlet Al Arabiya. The accounts tweeted in three batches. The first batch of nine accounts tweeted between 8:28am and 8:32am and included the same text as the Al Arabiya post but removed the hashtags. A second batch of nine accounts tweeted between 9:55 am and 9:58 am and included a cropped version of the original Al Arabiya tweet, removing all references to Al Arabiya. The third batch comprising six accounts tweeted between 11:31am and 11:36am, using the text from first batch and the image from the second batch.

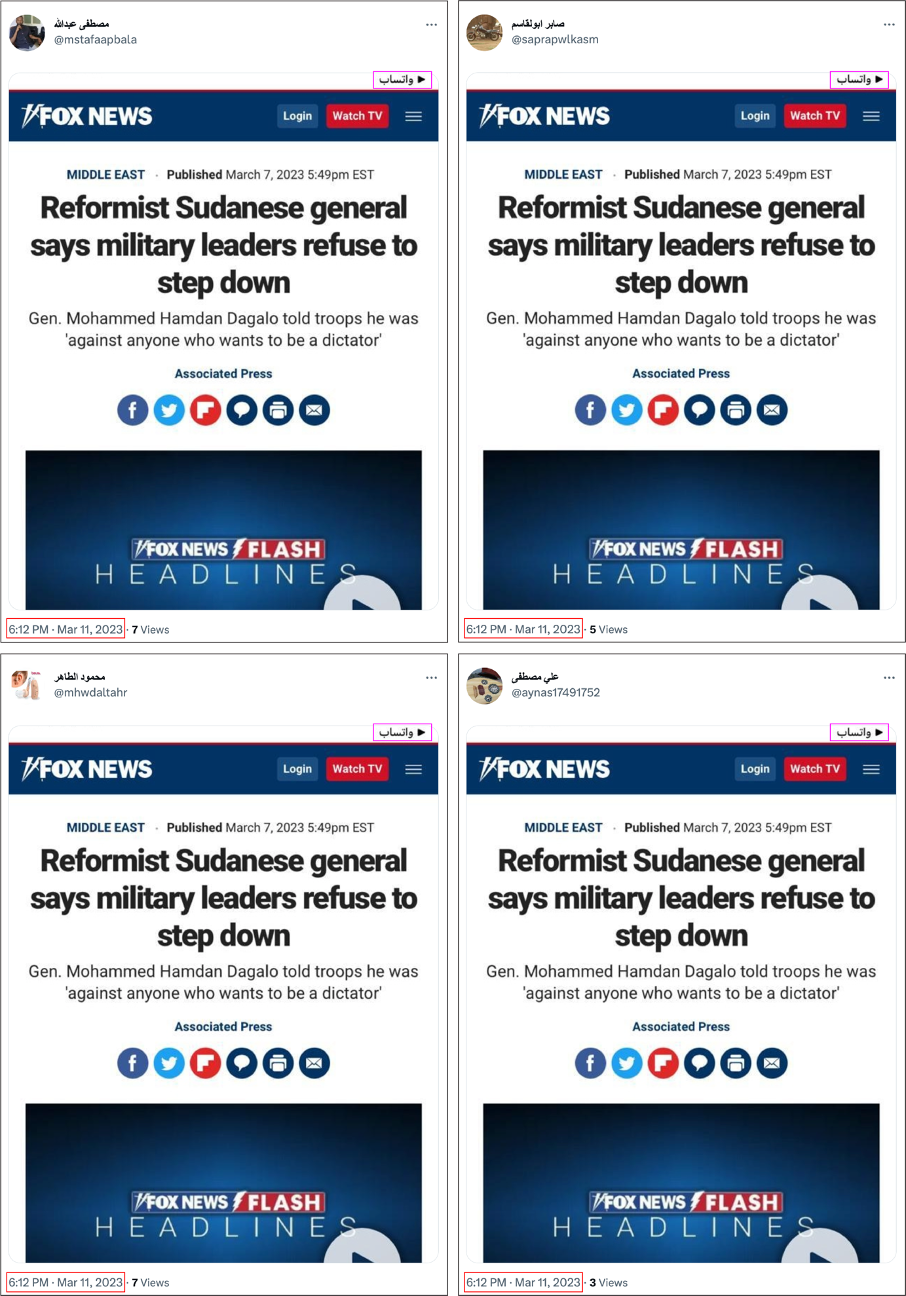

In another instance, on March 11, ten accounts posted a screenshot of a Fox News article within two minutes of one another. In the top right corner of the screenshot is a button that reads in Arabic, “return to WhatsApp.” This indicates that a link to the Fox News article was possibly shared in a WhatsApp group and the screenshot was taken when one of the group members clicked the link. While the article mentions Hemedti’s role in the October 2021 military coup, the screenshot of the article’s title is sympathetic to the paramilitary leader. He is separated from the other military leaders and presented as supportive of the democratic movement, even though Hemedti was still second-in-command of the military council ruling Sudan after the 2021 coup.

Other tweets written in English were also posted within minutes of each other, indicating a possible attempt to reach a larger, more international audience. In one example, four accounts tweeted identical text of what appeared to be an English summary of a tweet posted by Hemedti in which he stated that he would sponsor a conference that would be used to develop a ten-year plan to better develop Khartoum. The accounts posted within two minutes of one another, and three used the same picture of Hemedti.

Due to the copy-paste nature of the network, where large groups of accounts shared the same content within minutes of one another, the accounts themselves often had identical timelines. For example, the nine highest engagers often had almost identical timelines across days and even weeks.

Similar replies

The DFRLab observed that the accounts in the network frequently replied to tweets by the RSF and Hemedti using copy-pasted text or text that had been slightly edited to include or remove a word or two. For example, identical or very similar text praising Hemedti was used to respond to three tweets posted by the RSF. On January 17, the account @mhwdaltahr replied to an RSF tweet about a meeting between Hemedti, the attorney general of Morocco, and the Moroccan ambassador to Sudan, praising Hemedti by saying, “Hemedti is a man representing an entire country who works for the nation and the citizen.” The text was copied verbatim and used by @aynas17491752 on January 29 when replying to an RSF tweet about a meeting between Hemedti and Ethiopian Prime Minister Ethiopia Abiy Ahmed. Two months later, on March 26, the account @ahmdbas54698745 added a few words to the same text to reply to another tweet about a Hemedti speech, writing, “Hemedti is a man representing an entire country who works for the nation and the citizen, and to preserve safety, security, and stability.”

On March 29, meanwhile, the account @sakralart1123 replied to an RSF tweet with the text, “These forces [the RSF] greatly contributed to maintaining security, safety, and stability across the country.” Four minutes later, the account @mhwdaltahr removed one word and recycled the text to reply to the same tweet.

On March 25, accounts @sakralart1123 and @mstafaapbala replied to an RSF tweet promoting a YouTube video with the same text posted ten minutes apart.

At the time of publication, Sudan’s two military forces were still locked in conflict, both making claims online about territorial control and pointing the finger of blame at one another. The two networks identified by the DFRLab indicate that a portion of the RSF and Hemedti’s social media engagement could be coming from potentially hijacked and suspicious accounts attempting to influence the online narrative.

Cite this case study:

Tessa Knight, “Suspicious Twitter accounts artificially amplify Sudanese paramilitary leader amid armed conflict,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), April 19, 2023, https://dfrlab.org/2023/04/19/suspicious-twitter-accounts-artificially-amplify-sudanese-paramilitary-leader-amid-armed-conflict