Advancing the narrative: analyzing the maturation of Palestinian militant videos

Gaza militants increasingly use collaborative releases, advanced editing, and narrative-driven storytelling when sharing battlefield footage

Advancing the narrative: analyzing the maturation of Palestinian militant videos

Share this story

BANNER: EQB video still showing the unveiling M90 rockets. (Source: Telegram)

Editor’s note: The author has chosen to deliberately omit most links to the Telegram channels under discussion out of a concern for contributing to their further broadcast and, in some cases, because the channel has already been suspended or deleted.

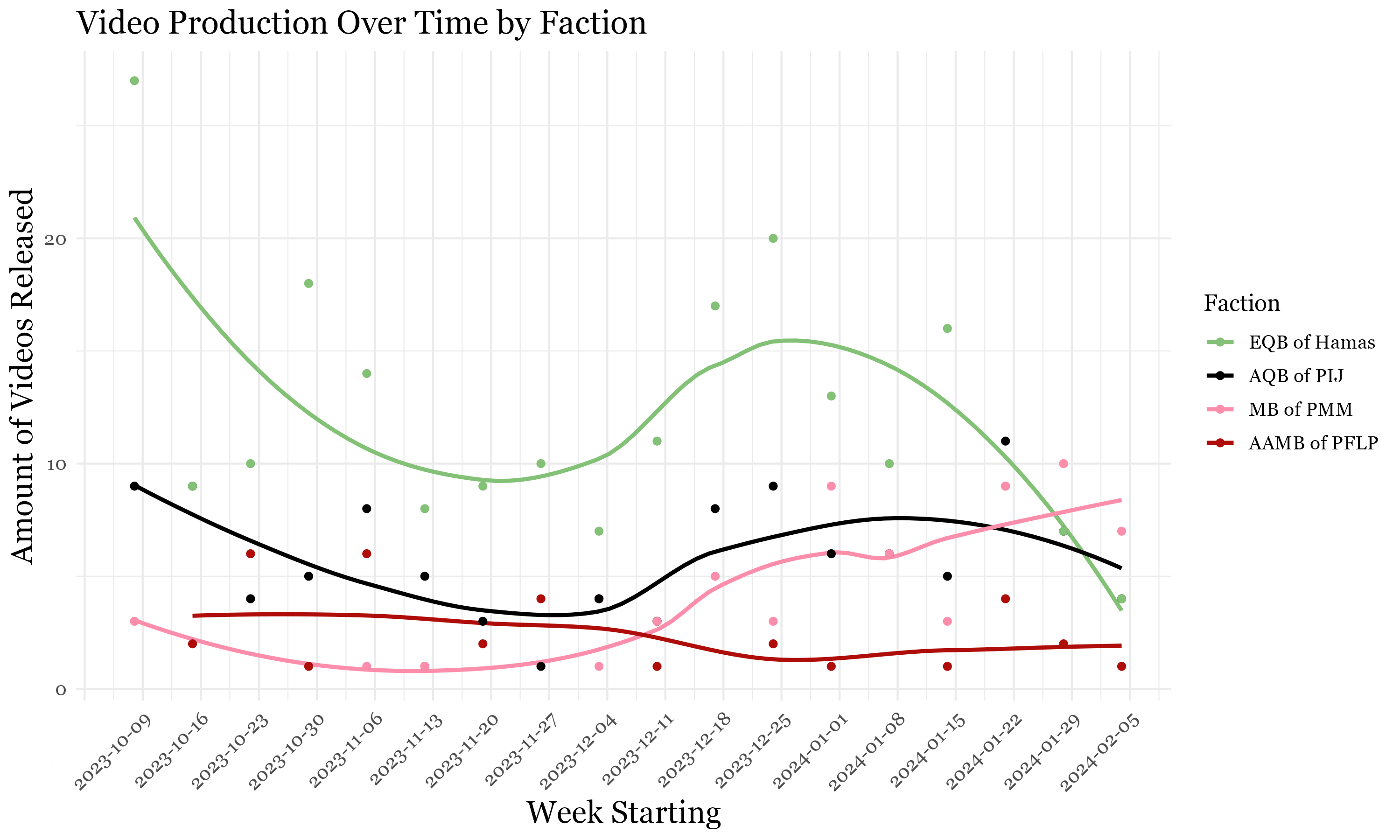

The video production techniques of Palestinian militant groups continued to evolve over the first four months of the ongoing war in Gaza. Not only are more factions producing video content, but in the time since our December 2023 examination of video production by Palestinian militant groups, they have increased their sophistication, such as through more advanced captioning and editing. There also appears to be an increased tendency for collaboration between the groups.

While armed Palestinian groups have produced scores of videos since October 7, the subsequent analysis is focused on official releases from Gaza-based armed factions. Thus, for a release to be included, it had to meet five requirements:

- The item is a video;

- Produced between October 7, 2023, and 12:00 a.m. on February 7, 2024;

- By a Palestinian armed faction currently fighting in Gaza;

- Released on an official, branded media Telegram channel of an armed group; and

- Primarily served to display military content.

Through daily review, 1,360 items were collected for initial evaluation. Based on the rules above, 831 items were excluded, typically because they were spokesmen’s speeches (i.e., not direct military content), focused on activity in the West Bank rather than Gaza, showcased allied attacks in other countries, or were not videos.

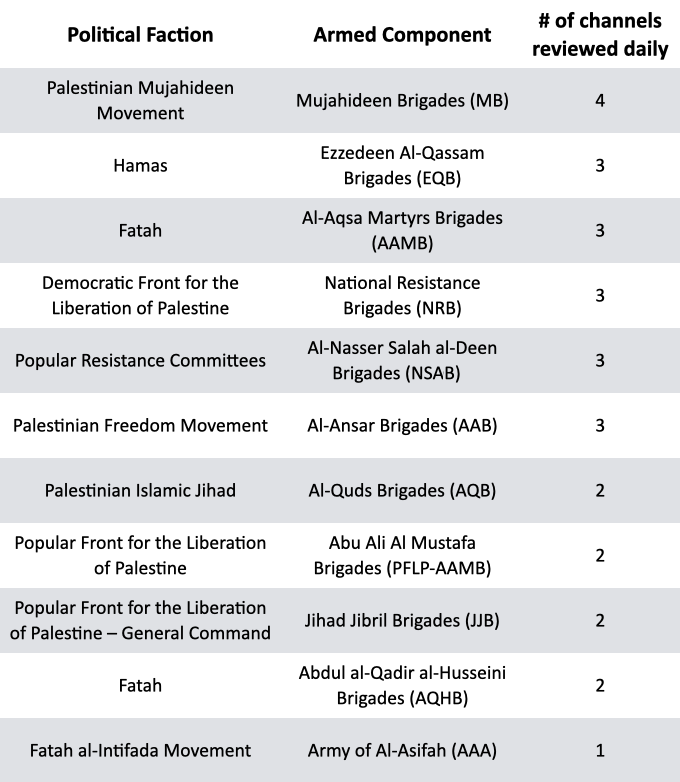

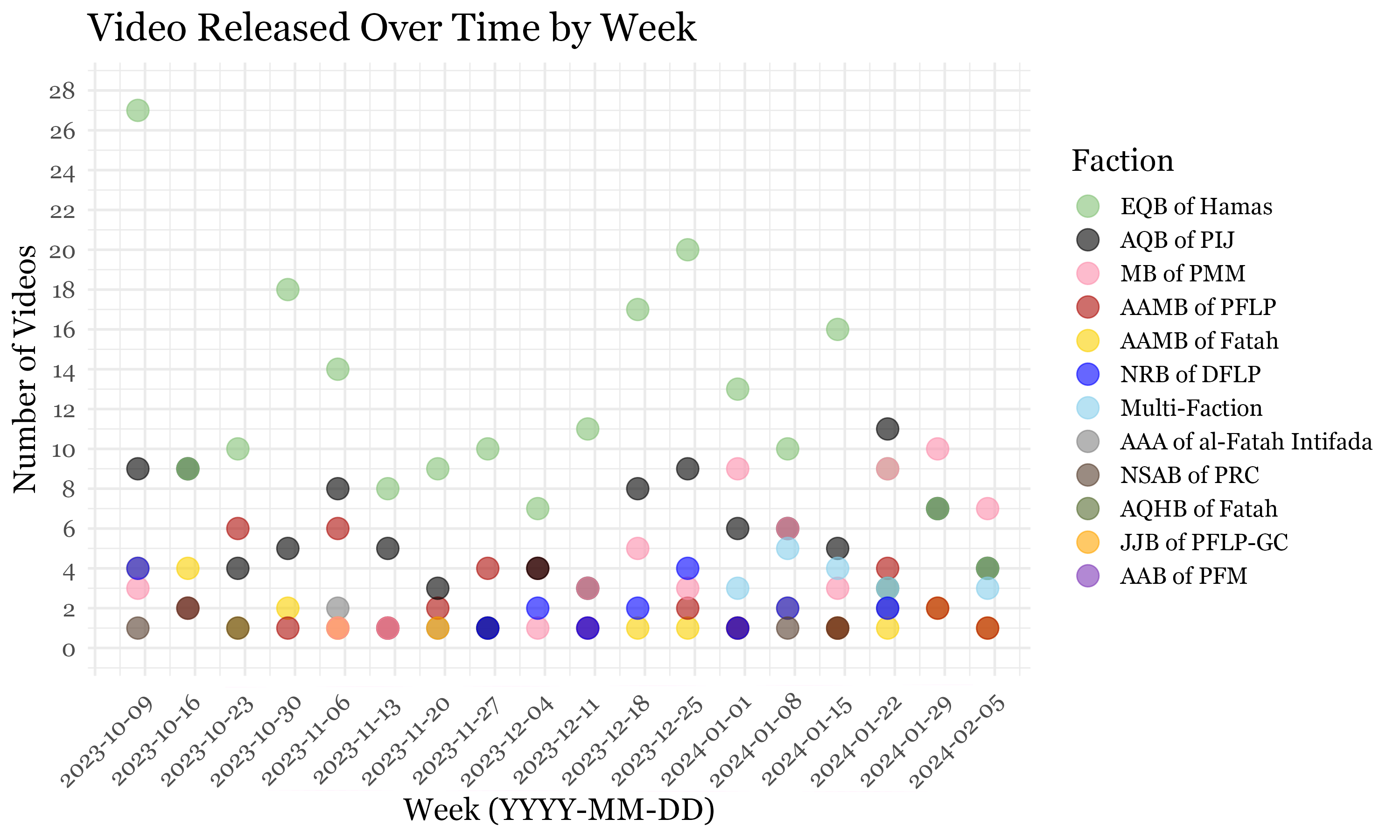

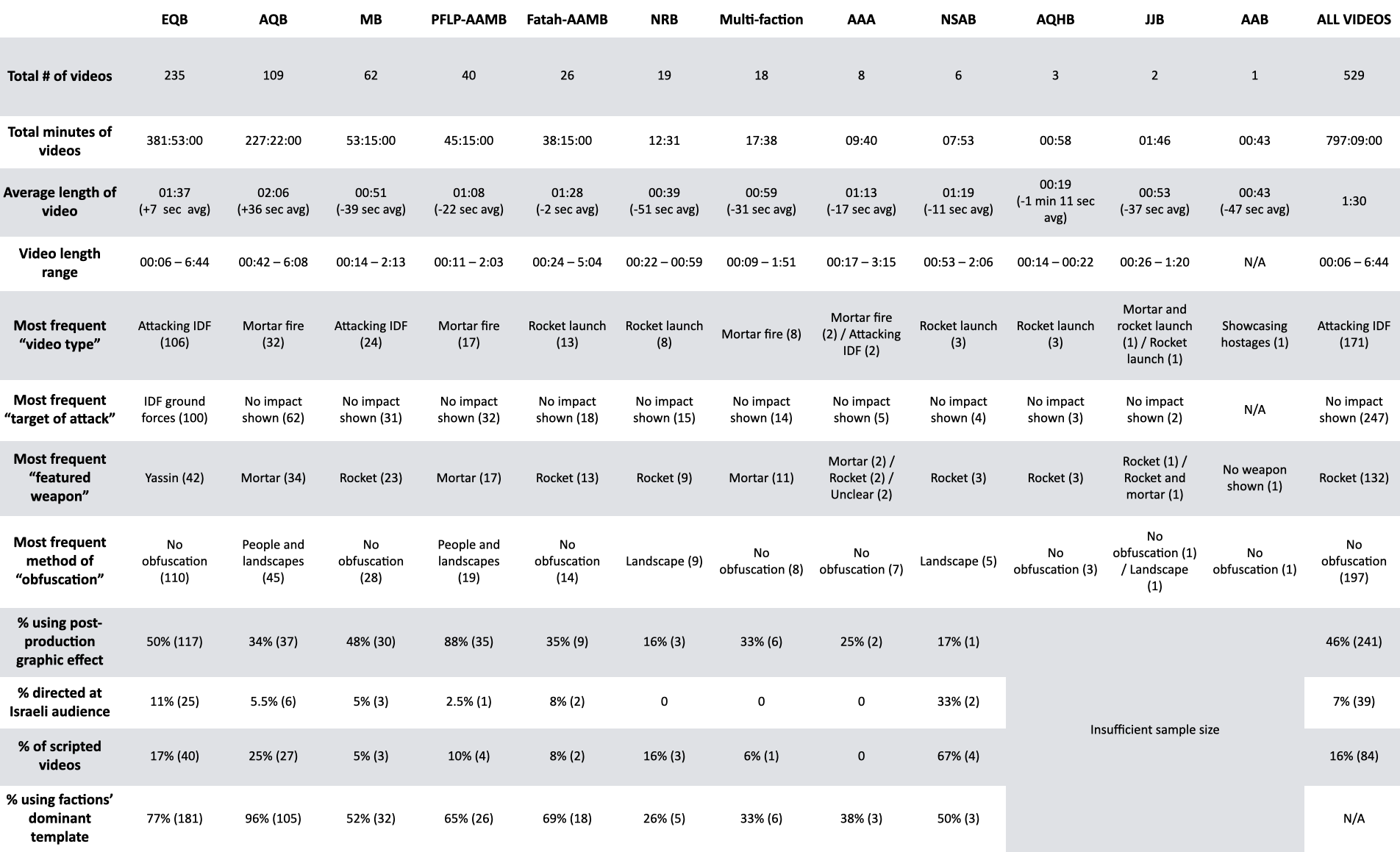

The subsequent analysis is therefore based on a forensic review of 529 videos produced by Palestinian militants in Gaza between October 7, 2023, and February 7, 2024. As best as can be determined, this constitutes the entirety of videos distributed through official channels throughout this period. After initially including only eight factions, the current study expanded this to eleven armed groups.

To comprehensively gather videos, we reviewed the daily feeds of twenty-eight channels in addition to thirteen unofficial aggregators. These secondary non-official channels were included to ensure no videos were missed. Each video was downloaded, reviewed, and manually coded for fifteen variables. Additionally, memoranda were authored for each video, taking note of stylistic, content-based, or other notable matters suitable for analysis.

While a great deal of quantitative data can be deduced from these data, the following discussion will focus on a qualitative review of some main themes.

Overall trends and analysis

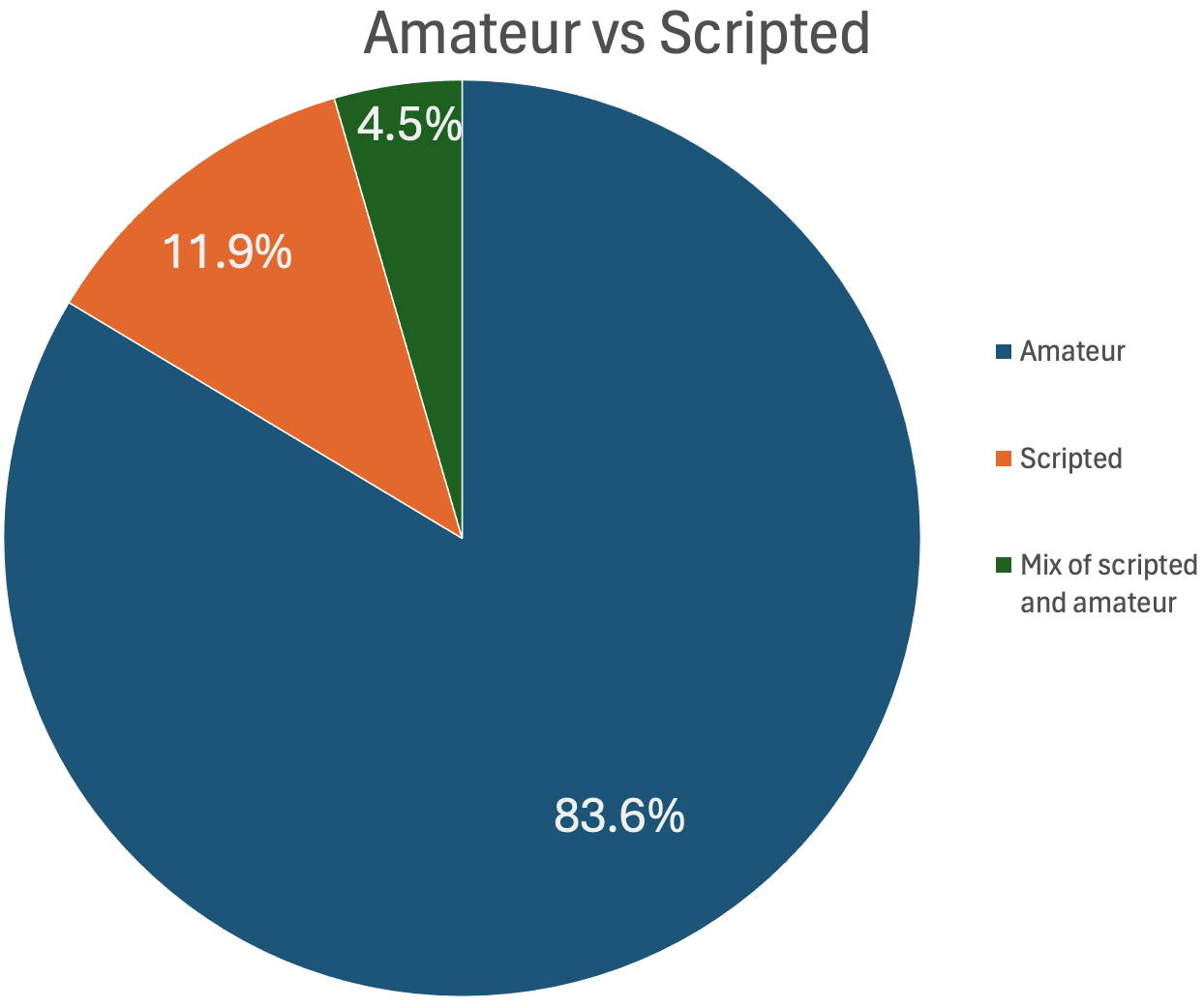

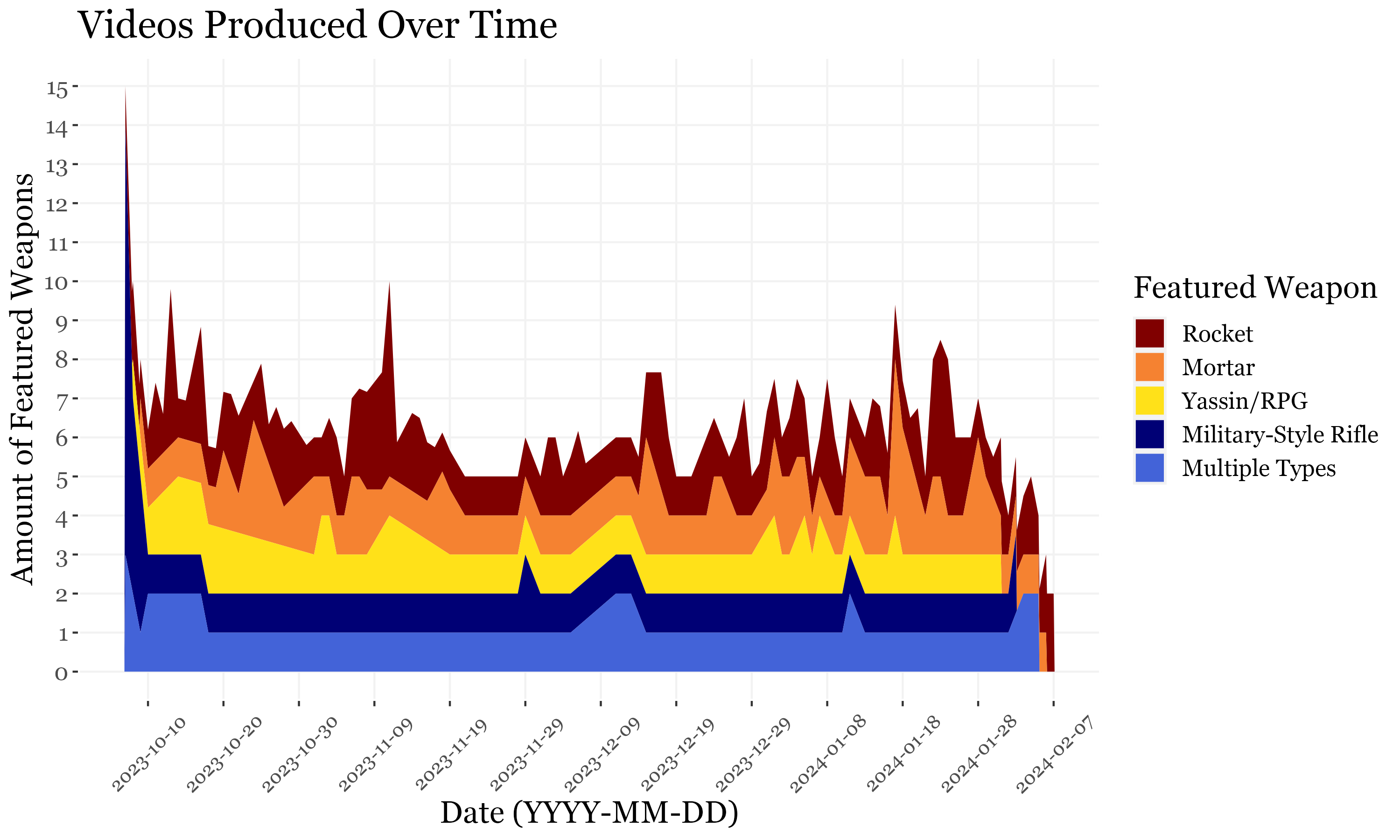

In order to determine overlapping themes, we first documented the mechanics of video production (i.e., frequency, length, templating, effects, obfuscation), content type (i.e., video type, scripted versus battlefield footage, audience), and military markings (i.e., target type, featured weapon).

There is much to remark on within a faction, between factions, and throughout the various armed groups. The brief synopsis, as seen in the table above, can be used to identify trends and outliers. A few notable summative trends include:

- Palestinian Islamic Jihad’s Al-Quds Brigades (AQB) has the highest overall production focus, with longer videos and the most frequent scripting and templating. Hamas’s Ezzedeen Al-Qassam Brigades (EQB) and, to a lesser degree, the Popular Resistance Committees’ Al-Nasser Salah al-Deen Brigades (NSAB), occupies a middle space with mid-length videos, less scripted content, and less uniformly branded templating while utilizing post-production effects (e.g., target markers, captioning, slow motion) more frequently. Comparatively, factions with lower production value include Mujahideen Brigades (MB), National Resistance Brigades, (NRB), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine Abu Ali Al Mustafa Brigades (PFLP-AAMB), and Fatah’s Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades (Fatah-AAMB), all of which utilize less brand uniformity (i.e., templating), shorter videos, and infrequent scripted content. Overall, across factions, non-scripted “amateur” video filmed on digital single-lens reflex cameras (DSLRs), smartphones, and GoPros is far more common than multi-camera, high-definition productions.

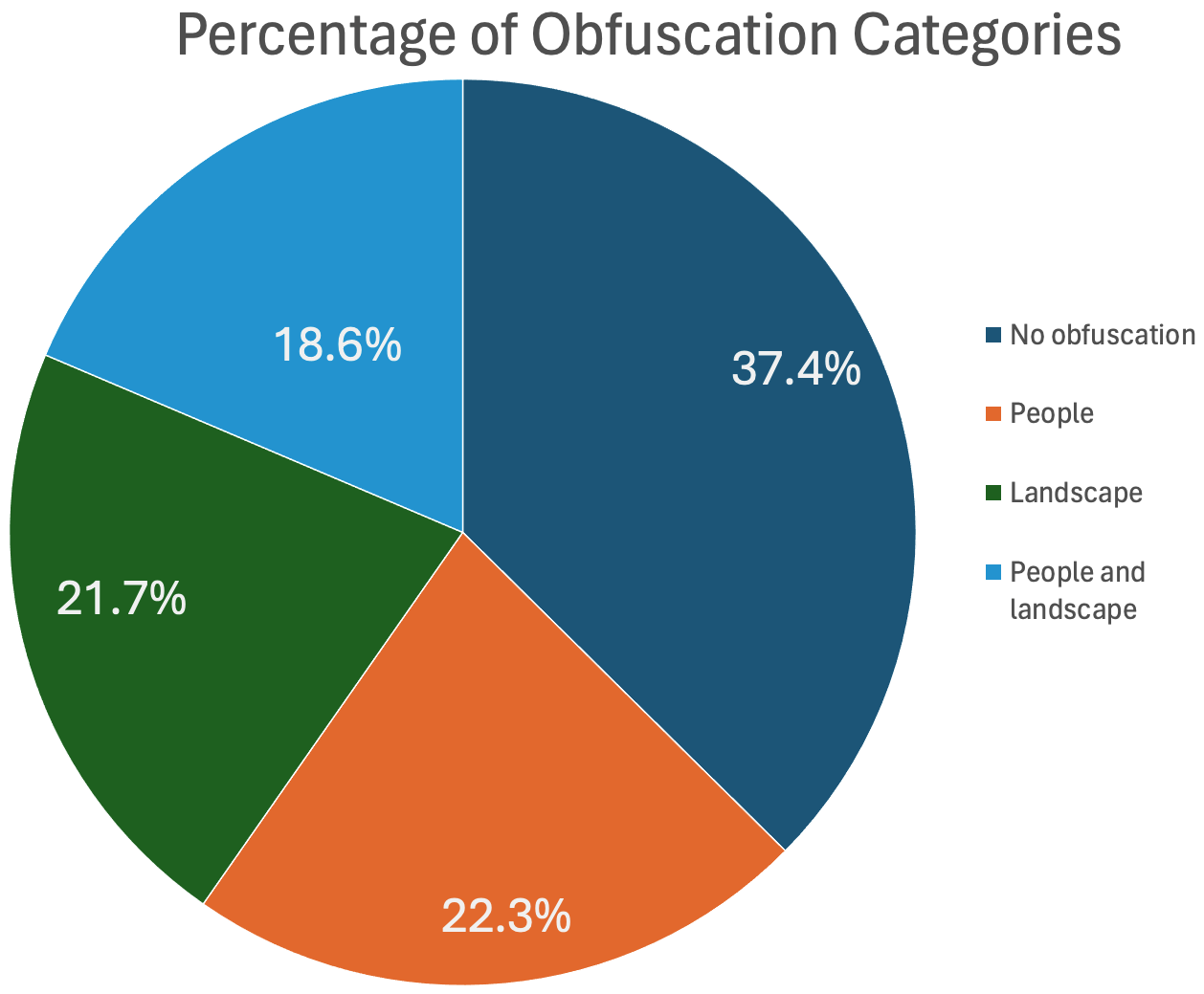

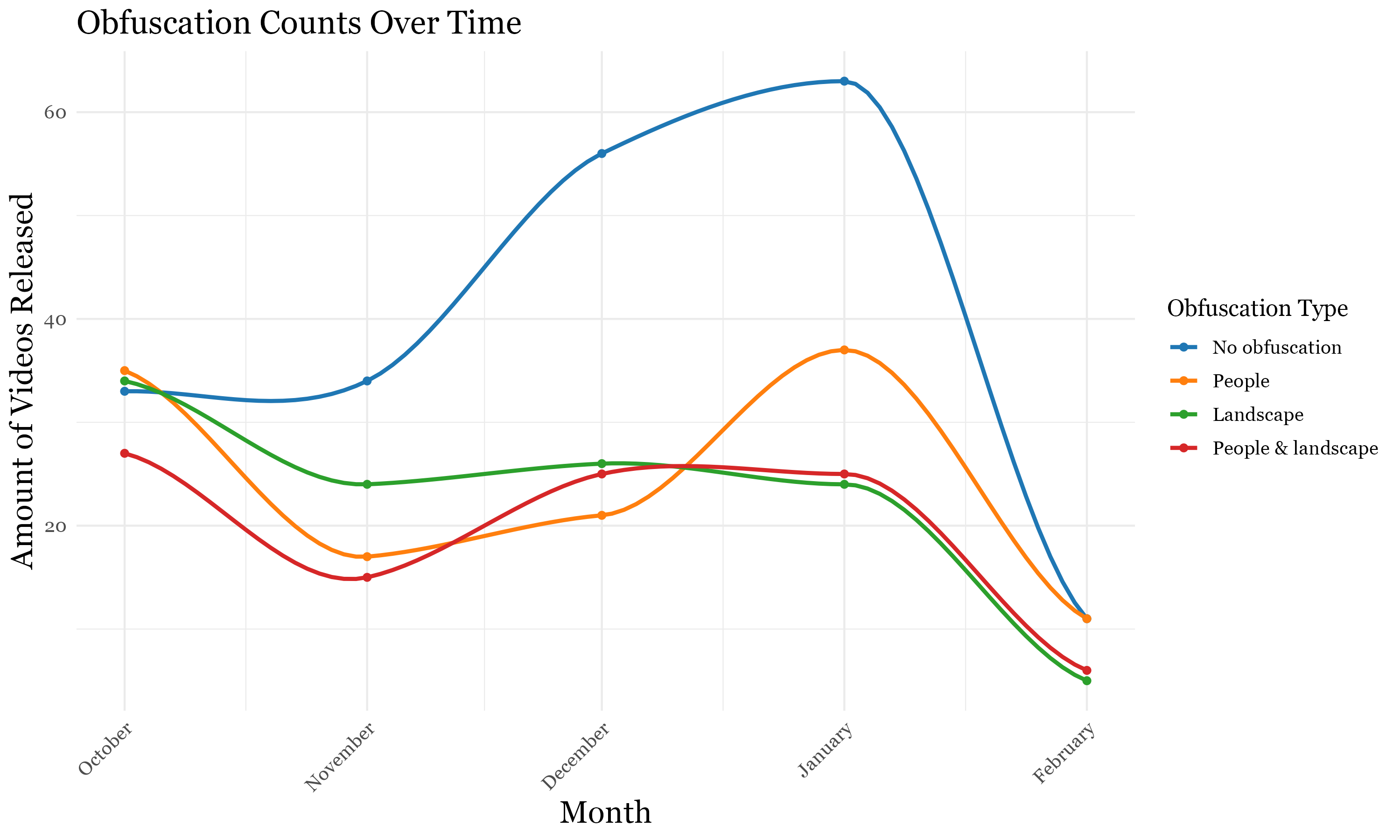

- EQB is the only faction whose videos focus on repelling and ambushing the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) (45 percent). As an effect, their attacks most commonly feature the targeting of IDF ground forces (43 percent), including soldiers, armored vehicles, and military infrastructure, often with mid-range weapons. Other factions are predominantly focused on longer-ranged, indirect-fire artillery weapons—mortars and rockets—and thus, the impact of the attack Is not shown. While a lot of videos lack obfuscation (37 percent), when it is used, the blurring of people, landscapes, or both occurs with notably similar frequencies.

- Factions are most likely to use obfuscation during a projectile launch to thwart the geolocation of rockets, mortars, and tunnel mouths.

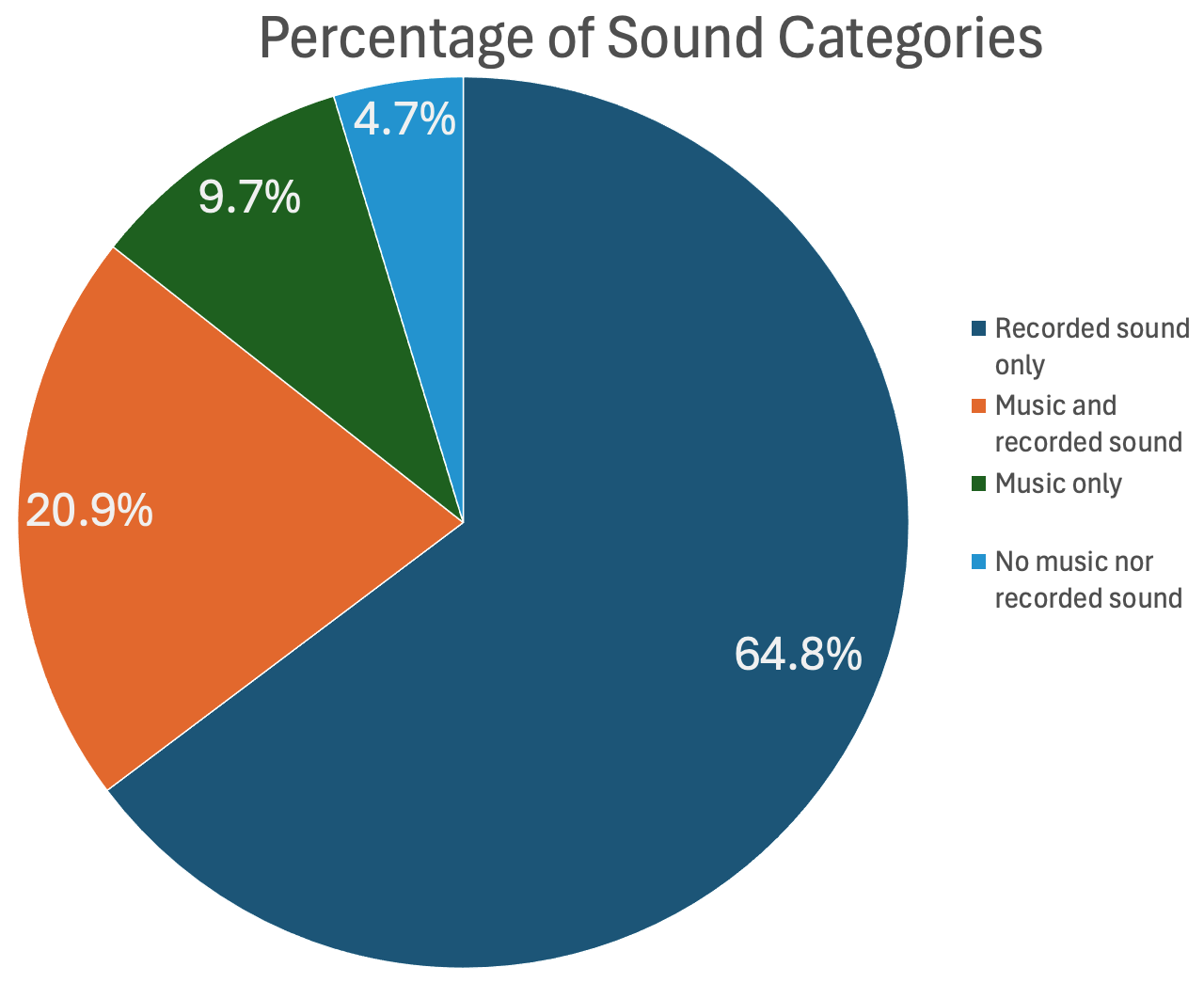

- Across factions, the use of music in videos is rare, which is a stylistic departure from Palestinian media produced in the second Intifada, which often featured stirring patriotic anthems atop video clips assembled in series.

- Explicit threats, Hebrew-language content, or videos otherwise directed at the Israeli citizenry or state are infrequent throughout all factions (7 percent), and most likely to be authored by NSAB (33 percent) and EQB (11 percent).

These trends provide the basis for the subsequent discussion, focused on a few themes: the emergence of new factions and multi-factional videos, the advancing narratives of video production, and how videos reflect the changing battlefield conditions.

New factions observed

During the investigation period, we identified three armed factions that were not part of our December 2023 study. Most notably, we identified eight videos from the Army of Al-Asifah (AAA), also known as the “Storm Forces,” the militant wing of Fatah al-Intifada, which broke off from the main Fatah party in 1983. AAA’s activity on the ground appears to be limited, and its online presence via the networks circulating Palestinian battle footage is scant. At the time of research, AAA’s largest Telegram channel had fewer than 400 followers.

Despite its small presence, AAA has produced at least twenty-two written communiques during the current conflict—typically a single sentence reporting a military strike—but did not publish any video content until November 6. In total, AAA has only produced eight videos, all of which display low production value.

Secondly, the Abdul al-Qadir al-Husseini Brigades (AQHB) published several videos, some of which were co-branded with AAA. AQHB was founded in 2012 and is estimated to have between 700 and 1,000 fighters in Gaza. Founded by former members of Fatah’s AAMB, AQHB infamously carried out a 2015 West Bank shooting attack killing two Israeli settlers, including a US citizen. Notably, the Gaza-based, AAMB-aligned Fatah factions announced their unification in 2021; according to Israeli reports, Hamas encouraged and facilitated this centralization.

Israeli intelligence reports have documented co-branded AQHB-AAA videos, several of which were published in January 2024. The reports indicate the existence of “al-Asifa Forces – Abd al-Qadir al-Husseini Battalions,” noting that the factions have issued joint releases, such as a November 2019 statement on the killing of Thaer al-Abd Hamed in Beit Lahia, Gaza. Other Fatah formations that appear to be actively engaged in combat in Gaza have not produced any video content. One such faction is the Ayman Gouda faction, which has reported activity in Gaza but not released any video in the current phase of fighting despite reporting on other activities, such as slain fighters.

When it comes to releases by smaller factions, Al-Ansar Brigades (AAB) released only a single video during the initial wave of attacks on October 7, 2023. AAB is the military wing of the Palestinian Freedom Movement, founded in 2007 by former Fatah fighters. The short 43-second video adopted EQB’s template with a customized watermark. The video reportedly showed the militants “captur[ing] a number of [Israeli] settlers” on October 7, but the video is difficult to decipher and verify.

Collectively, these three minor factions are responsible for twelve videos, only 2 percent of the total corpus, and thus have a low impact on the overall findings and trends.

Multi-faction videos emerge

A notable change in the production of militants’ videos has been the rise of multi-faction publications—co-branded videos featuring more than one faction. The first of these was published nearly three months into the war; since then, a further eighteen appeared between January 3 and February 6, 2024. Such releases point toward increasingly cross-factional coordination and cooperation, something the Palestinians have experimented with via their “Joint Operations Room,” which coordinates military action between factions.

While multi-faction videos do not indicate the degree to which collaborations are occurring, it does point to some coordination. In many releases featuring two armed groups, both factions published their own versions of the same attack. This phenomenon can be seen in two videos released on January 10 by AQB and NSAB. In these videos, AQB and NSAB fighters are shown firing mortars in northern Gaza.

While the AQB release features a large digitally obfuscated mask, the NSAB release does not, despite showing the same individuals. The NSAB video features co-branding, with both factions’ logos displayed on the initial splash screen and throughout the video. This manner of co-branded dual releases occurred several times.

In mid-January, both Fatah-AAMB and AQB published videos of the same co-branded mortar attack on IDF ground forces in Khan Younis. AAMB-Fatah’s version can be identified from the website watermark, and AQB’s from the distinctive yellow triangle used by the group. Published the same day, the two videos showed the same two fighters. In both versions, the producers use split screens and captioning to describe the attack’s sequence, speaking to further cross-factional learning, adaptation, and upskilling.

Fatah-AAMB and AQB produced numerous co-branded dual releases using the same pattern, always showing mortar teams in front of factional banners with affiliations demarcated with headbands. Throughout these cross-factional releases, fighters are universally shown in factional clothing (e.g., headbands, patches) and in front of factional flags. The development of rapid, clustered releases of co-branded videos may speak to greater on-the-ground coordination between fighting organizations or, at minimum, an agreement to present that as an outward image.

EQB’s continued advancement narrative

While new, smaller factions and multi-faction collaborations provide insight, the most notable observations come from Hamas’s EQB. What is inescapable in the analysis of EQB’s video production is their frequency: 235 videos in the first four months of the war. Throughout this period, EQB produced more than twice the number of videos as AQB (109 videos), the second-most prolific producer. Excluding AQB, EQB produced more videos than all the other factions combined (185). The reasons for EQB’s prominence are many: not only is it the proscribed leader of the war effort, but it is also the largest faction in Gaza, a quasi-state force, and reportedly is the recipient of economic aid from outside backers, including Iran. With up to 30,000 fighters, it has maintained a media production unit since at least as early as 2004, producing website and video content.

Through its videos, EQB must promote itself as resilient to Israeli bombardment, able to continue the production of advanced weaponry, and possessing a seemingly inexhaustible stockpile of military hardware, fighters, and motivation. For EQB, it appears as if small periods of calm may contribute to the advancement of the militants’ video production abilities. The first video, released after a period of calm from November 24 to December 1, 2023, showed several new video advancements that have since persisted. In a December 2 video, producers included the extensive use of on-screen captions to tell a more complicated story, adopt multiple forms of target markers and crosshairs, and begin using instant replay and slow-motion replay.

![Video still stating EQB is “monitoring [IDF] forces," narrating their action with captions. (Source: Telegram)](https://dfrlab.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/03/2024.03.04-Loadenthal-11.png)

In a video published on December 13, EQB fighters can be seen inside of a school, engaging IDF soldiers. The video is long—nearly five minutes—and shows prolonged firefights narrated by on-screen captions. The video puts particular emphasis on spotlighting harm inflicted against IDF soldiers, even captioning when injured soldiers can be heard screaming off-camera. During the screaming, the on-screen video adds very little and functions to allow the screams to be heard. The video serves to present the audio.

Other portions of the same video show rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) targeting fast-moving armored vehicles and soldiers, with EQB fighters shown approaching and inspecting an unguarded IDF vehicle and taking down an Israeli police flag. These displays are means to exhibit EQB’s control of the battle arena, encapsulating their attempts to set the pace and conditions of conflict. These video and narrative tools, taken collectively, have been critical in advancing video productions that push toward more narrative-driven stories documenting complex attacks.

Beyond promoting more complex and engaging narratives, EQB continues to present an image of an innovative, tactically advanced, domestically equipped movement. In a late December 2023 video titled, “We will continue killing your soldiers by our locally manufactured snipers,” teams of masked fighters are shown manufacturing .50 caliber anti-materiel rifles and ammunition patterned after the Iranian AM-50. Despite Iran’s well-known provision of weapons to the Palestinian brigades, EQB claims to manufacture the “Ghoul” rifle itself. It has utilized the weapon since at least 2014. While the claim of domestic production could certainly be true, some have raised well-founded suspicion. EQB’s repeated claim that the weapons platform is Gaza-produced speaks to EQB’s desire to promote an image that they can sustain supply chains and manufacturing capabilities during the IDF’s siege, a key counter-narrative claim in a guerrilla war of attrition. Such a narrative construction and promotion can also be seen in a late January 2024 release from AQB in which the brigade is shown mass manufacturing shrapnel-filled explosive devices in an apparent attempt to assert that despite Israel’s efforts it can still maintain its manufacturing powers.

Innovation is another lead component of the Palestinian grand conflict narrative espoused by the militant groups. In an early December 2023 release, EQB showcased the M90 rocket, the largest in its arsenal that is also reportedly produced domestically. EQB announced the long-range rockets in a scripted, high-production video displaying scores of rockets concealed under a desert-color tarp and fired via multiple launch rocket systems.

Three weeks after the release, at midnight on December 31, EQB launched approximately twenty-seven M90 rockets, many visible over Tel Aviv. EQB claimed responsibility via its Telegram channel at 12:01 a.m. on January 1, 2024. The ability for EQB to manufacture, conceal, and launch frequent volleys demonstrates the faction’s supposed resiliency, itself a key element of the Palestinians’ warfare strategy and narrative. With each M90 launched, EQB showcases its ability to continue hiding massive weapons, an apparent attempt to counter claims that its capacity is degraded.

Evolving narrative structures through video editing

As the largest group in this arena, EQB is a frequent innovator in the realm of maturing battlefield narratives. It pioneered the use of target markers to make difficult-to-follow GoPro footage easier for viewers to interpret and to serve as a better reinforcer of the group’s battlefield narratives. Starting in December, EQB increased its use of captions and its ability to narrate increasingly complex operational stories. These innovations continue the trend that began with the red triangle target marker. Through advances in post-production editing, EQB authors its violence as legibly as possible.

This progressively sophisticated manner of sequential storytelling is not reserved to EQB, though it presents the largest number of relevant videos. AQB, a faction already known for prioritizing complex storytelling with higher production, has similarly adapted. In a video published in early January, AQB describes a late December 2023 attack as a “qualitative operation…targeting [an] enemy command and control position.” The video shows a series of sites, all carefully captioned, and the attackers’ preparations before the IDF is engaged.

After the video points out various IDF targets (e.g., “communications and eavesdropping devices and surveillance cameras”), fighters are shown positioning short-range rockets in a neighboring building for their assault.

After sufficient preparations are completed, the video shows the rockets’ impacts on IDF positions before the perspective changes to a split screen in which mortar fire can be seen supporting the attackers.

After showing the impact of the mortars, the caption reads, “Shells and missiles fall on the enemy’s command position and cause direct hits,” further developing the narrative for the viewer. With the assistance of digital crosshairs, the viewer is shown smoke rising from an impacted area as heavy gunfire and explosions can be heard. In the final scene, IDF jeeps are shown driving away from the scene with on-screen captioning that reads, “…jeeps…escaping outside the operation area.” In total, the nearly five-minute video shows a simple chronology, made easier by on-screen captions, occasional narration by an off-camera individual, and split screens to show projectile launches and impacts. This manner of video production shows increasing sophistication in not only digital methods but also in narrative construction and storytelling.

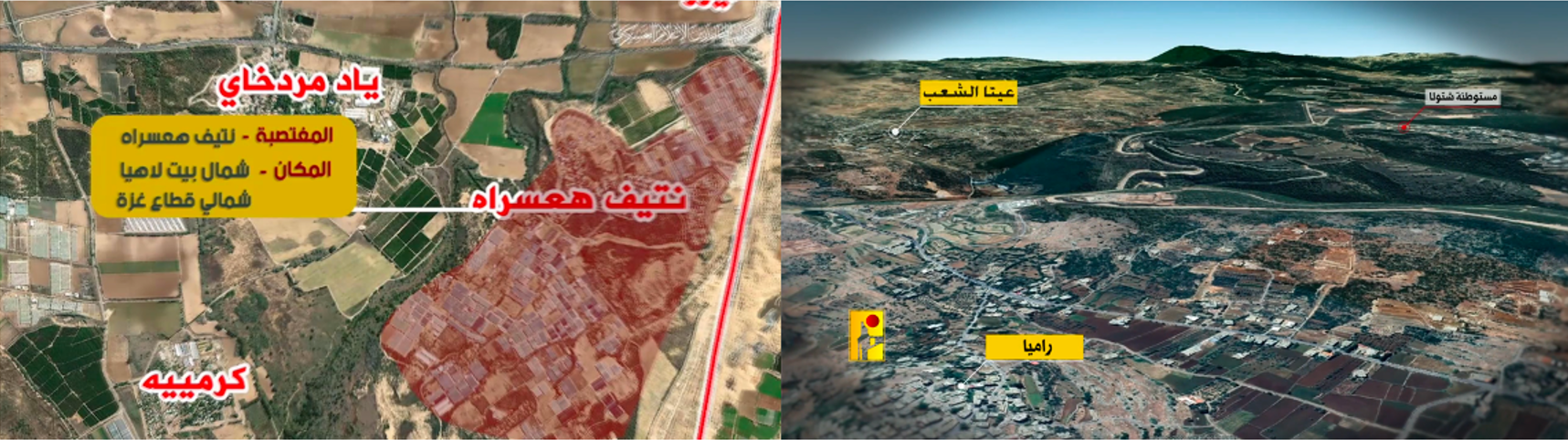

Although producing fewer videos, MB has employed more complicated narrative construction as well, beginning some videos with a terrain map to telecast for the viewer where the attack about to be shown took place. This method mirrors an approach utilized by Hezbollah: beginning many videos with a map to orient the viewer and mark targets, ensuring the action that follows is easier to interpret.

The narrative trend is also present in updated uses of typical video genres. Traditionally, mortar and rocket videos featured only launches—the projectiles are fired into the sky and with no impact visible. In only 2 percent of projectile videos are viewers shown the impact of projectile strikes. Amongst the videos constituting the 2 percent—four from AQB and one from EQB—a more complicated story is told, one wherein rockets and mortars are not simply flung into the air but also where they hit targets.

Some videos incorporated mortar fire into more complex narratives and attack sequences, such as a January 12 video from AQB that showed mortar teams supporting an ambush focused on detonating explosives surrounding IDF ground forces.

In this video, the viewer is guided through a multi-stage attack using captions, fighters’ narration, target markers, and other elements, to not only convey the complex sequencing of the attack but also to showcase the IDF’s efforts to evacuate casualties. This narrative construction was not present within the more simplified videos utilized in the first months of fighting.

In another video, similar captioning tells the story in seven scenes:

“Communications and eavesdropping devices and surveillance cameras…A command and control position for enemy forces inside Abu Oreiban, south of the Gaza District…Preparation of the guided 107mm rockets for direct targeting…Preparation of the 107 rockets for arc targeting…Directly targeting the command and control position with 107 rockets…Directly targeting the command and control position with mortar shells…Mortars and rockets fall on the enemy’s command position and achieve direct hits…A number of jeeps were monitoring escaping outside the area of the operation.”

This trend of showing complex sequences through the aid of narration also extends to rocket launches, which are typically very formulaic. MB produced a short 37-second video in early January showing a rocket launch that uses captioning to point out the “archer” (i.e., fighter) and the launcher, which is partially concealed in the landscape.

Using arrows, a white triangle marker, and text, the viewer is guided through the footage in a way specified by its creator. Collectively, these developments in post-production editing and storytelling are an advancement in the brigades’ ability to frame their attacks with greater control, promoting the image of a tactically advanced fighting force with a high degree of operational effectiveness.

The changing pace of battle

The pace of videos, as representative of video releases overall, demonstrated the changing tactics on the ground. Following a reduction in airstrikes, as traps, sniper fire, and ambushes became more routinized with expanded ground fighting, video releases increasingly showed direct hits on ground forces, including obvious fatalities.

The culmination of more than twenty years of reported development, the shoulder-fired Al-Yassin 105 anti-tank RPG continues to heavily feature in factions’ releases, especially those of EQB. It is the most consistently displayed non-artillery combat weapon.

According to EQB, in the current round of fighting, the Yassin has damaged or destroyed “1,108 vehicles, including 962 tanks, fifty-five troop carriers, seventy-four bulldozers, three excavators, and fourteen military jeeps.”

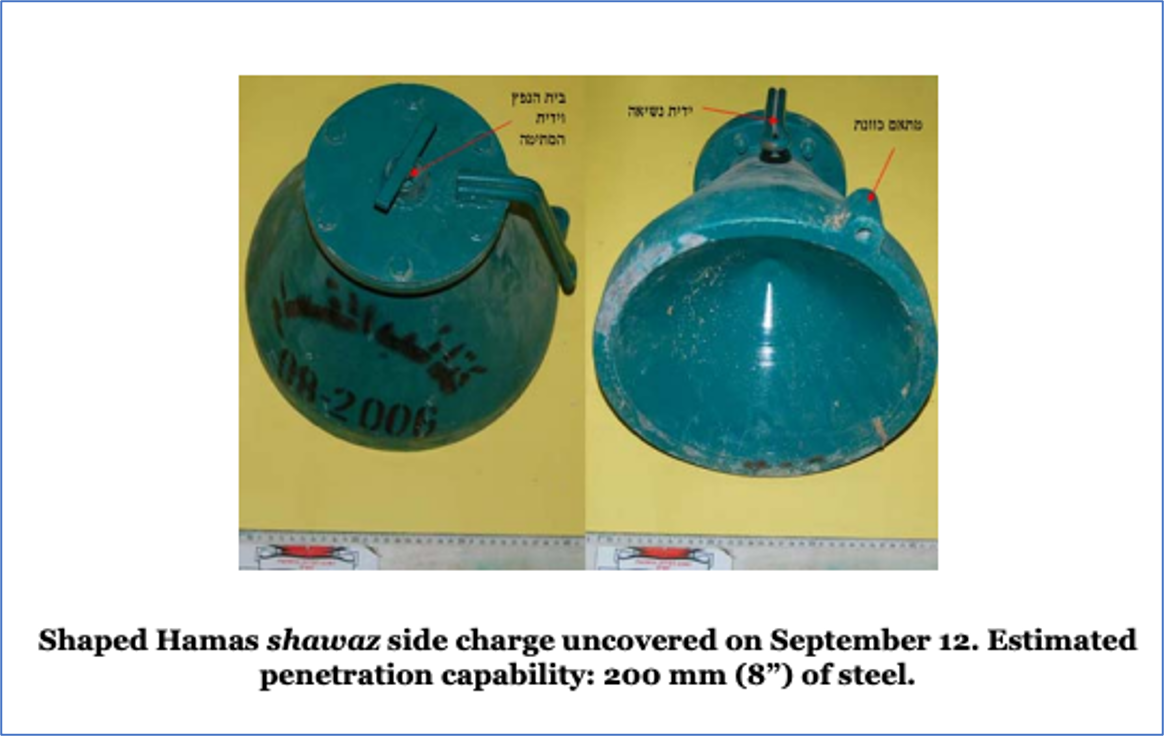

Despite the continued popularity of the weapons platform in ambush videos, Palestinian forces have keenly displayed other weapons, such as the Shawaz-1. The Shawaz is an explosively formed penetrator (EFP), a shaped explosive charge that effectively penetrates vehicle armor. The use of EFPs appears to date back to the 1930s when they were used in the oil industry during digs and installations. Their weaponization was reportedly developed by Iran, and they have been used for decades by non-state actors. The Marxist-Leninist Red Army Faction utilized one in the 1989 assassination of Alfred Herrhausen, and, more recently, they have become a mainstay of Iranian-backed attacks carried out by Hezbollah and militia forces in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine.

The use of the Shawaz in the Palestinian arena dates back to at least the early 2000s, when Israeli intelligence analysts attributed them as being “modeled” from Hezbollah. While Shawaz EFPs have been used prior to the current war, their deployment in the current round of fighting has been featured in at least six videos. EQB has occasionally deployed other varieties of EFPs, such as the Shuath, which it claims is armor-piercing.

Other factions have also showcased new weaponry, including anti-personnel projectiles (e.g., OG-TV 40mm fragmentation rounds), anti-personnel “lighting” explosives fired from rifles, MB’s repeated use of modified Sa’ir “missiles” (i.e., unguided 55mm S-5 rockets with a customized launcher)targeting naval forces, ground forces, and armored vehicles, and the group’s use of surface-to-air missiles to target Israeli aerial assets.

Other videos provide additional insight into the changing nature of battle in Gaza. In a notable release by AQB, numerous mortar teams are shown firing projectiles using handheld mortar tubes that are devoid of the more traditional bipod setup. In this more mobile configuration, fighters support the neck of the launcher and seem to anchor the tube slightly into the ground to form an ad-hoc baseplate.

The fighter shown in the above image possesses an engineer’s hammer, presumably to help dig the anchor hole for the launcher, and a kaffiyeh to cradle the tube. In another scene, a fighter can be seen using a rock to break up the paved street to position a mortar tube. Throughout the nearly two-minute video, seven mortar crews are shown, six of which utilize handheld, bipod-less launchers. EQB also showcases the use of handheld launchers in a video released within 24-hours of AQB’s, possibly pointing to a coordinated strategy between factions to utilize these nimbler mortar teams, likely the result of changing battlefield conditions and the need for increased mobility. This is yet another vignette into how the changing realities of combat have influenced weaponry and tactics, which are then carried forth via video productions, allowing the videos to capture and externalize the facts on the ground.

Conclusion

This second study further supports the hypothesis, proposed prior, that, through an event-based, content analysis of video production, one can approximate the pace and conditions of the wider conflict. Put another way, video types and components change in lockstep with the on-the-ground military and political conditions. This is most clearly shown in the pauses in military videos during the period of the prisoner exchange—November 24 to December 1, 2023—and in a second period, beginning around January 27, 2024, in which a further pause in hostilities was being negotiated.

While videos released on or around October 7 were most likely to show attacks on IDF bases, those that followed, before the ground invasion, featured longer-range weapons, and, following the deployment of IDF ground forces, videos again shifted to ambushes and shorter-range attacks on troops and vehicles. Tracking video releases in this manner—their pace, taxonomy, and content—can provide insight into how armed groups perform tactically, organize strategically, and communicate outwardly.

This period of fighting, marked by a one-week ceasefire and months of hard-fought ground combat, points toward a growing and sustained focus on presenting the factions through the lens of ingenuity, resiliency, tenacity, and the ability to inflict casualties while under siege. As the war moves into its fifth month, we are likely to see a continued focus on battlefield narration and a steady focus on controlling the storyline through a constant release of material.

Indeed, since completing data collection for this piece on February 7, 2024, the DFRLab’s predicted decline in video releases has sustained. During the pre-negotiation period, the most frequent producer, EQB, produced on average two videos per day (224 videos over eleven days). Since ceasefire negotiations were announced publicly on January 27, its daily release rate has decreased to a half video per day on average (twenty videos over thirty-four days). Between February 7 and March 1, EQB only published nine videos, amounting to 9 percent of the releases in this period. During this pause for EQB, other factions such as MB considerably increased their rate of production (forty-three videos), alongside an increased release of multi-faction videos (seventeen videos).

Dr. Michael Loadenthal is a contributing writer to the DFRLab. He is an Assistant Research Professor at the School for Public and International Affairs at the University of Cincinnati, focusing on political violence, threat modeling, and security practices within extremist networks. He also directs the Prosecution Project (tPP), a political violence analysis platform, which he founded in 2017.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Carter Langham, an undergraduate student at Regis University and Associate Data Scientist with the Prosecution Project (tPP), for producing the data visualizations used throughout. Carter is currently assisting tPP with its Accelerationism Taskforce and a project studying crowd-sourced policing used in US Capitol riot investigations.

Cite this case study:

Michael Loadenthal, “Advancing the narrative: analyzing the maturation of Palestinian militant videos,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), March 11, 2024, https://dfrlab.org/2024/03/11/advancing-the-narrative-palestinian-militant-videos.