Spanish-language ads amplify scams using audio deepfakes of public figures

Scammers fabricated interviews with politicians and tech moguls to present supposed investments as legitimate government-backed programs

Spanish-language ads amplify scams using audio deepfakes of public figures

Share this story

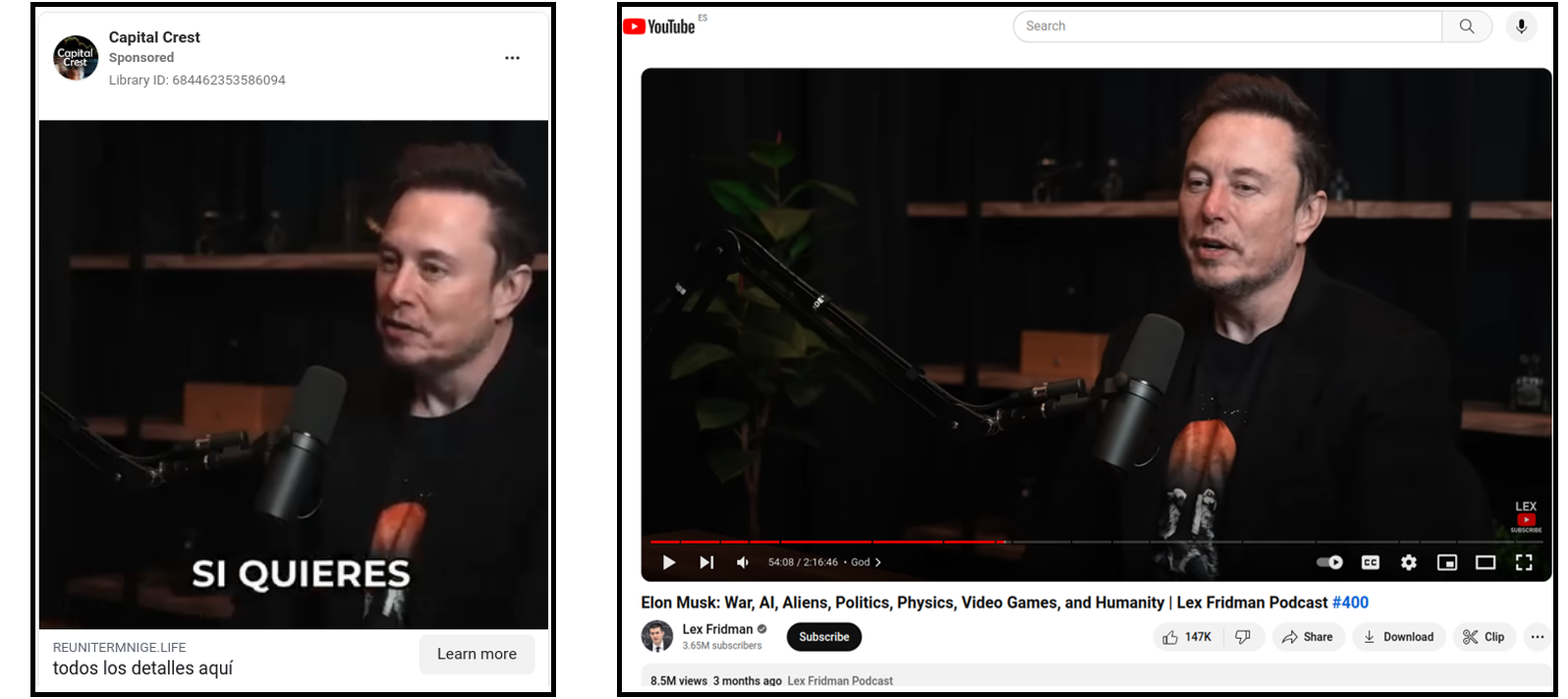

BANNER: Screenshot of Facebook ad featuring Elon Musk, whose voice has been altered to promote a scam.

Hundreds of ads promoting investments in fake government projects and dubious cryptocurrency-trading platforms used deepfakes purporting to show interviews with well-know individuals, including politicians and tech entrepreneurs. The advertisers targeted thousands of Meta users in Europe and Latin America. Several media outlets unmasked the investments as scams, and Meta has removed many of the ads. Yet at the time of writing, the owners of the pages have managed to keep their paid campaigns active while successfully impersonating others and preserving their own anonymity.

A DFRLab analysis of twenty-seven pages that paid for ads on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger to target Spanish-speaking audiences between August 2023 and January 2024 showed that the scammers utilized deepfakes to make their supposed investment platforms appear trustworthy. These ads led users to websites to obtain their contact information, promising that a person would contact and guide them through the process of making an initial “investment,” which was usually a minimum of $250 dollars or euros.

Data collected from Facebook pages, Meta’s Ad Library, and public registers of Web domains showed that individuals or organizations operated clusters of Facebook pages and websites in a coordinated manner, targeting Spanish speakers in Spain and Latin America.

In response to the fake ads, Spain’s National Securities Market Commission denied any authorization to invest in Quantum AI, one of the most mentioned cryptocurrencies in the videos analyzed. Spanish-language media outlets whose content has been used to make the manipulated videos have also investigated the deepfake videos. The DFRLab previously identified a similar sketchy operation that invested in Facebook ads that used altered photos of a Polish politician to drive Meta users to suspicious cryptocurrency-related websites.

Quick earnings from inauthentic sources

In general, the ad videos followed a similar narrative structure: the ads would claim that leading political figures and their advisers were secretly using the investment app and that a tech mogul would soon launch the app exclusively in the country being targeted. Ads would also claim that the entities launching the investment platforms were doing so to ease poverty or inflation and that artificial intelligence (AI) would allow new users to see quick profit returns with a 95 percent chance of success. Most videos also ended with a clip of a famous individual appearing to encourage users to visit the website and “learn more.”

The ads routinely featured AI-generated footage of public figures endorsing the platform, including presidents and presidential candidates appearing to describe the investment as a governmental program. Fake clips also featured journalists purportedly interviewing politicians, tech entrepreneurs, or actors, utilizing fictitious news coverage. Among those utilized in the fake videos were Mexican businessman Carlos Slim from Mexico and Real Madrid president Florentino Perez. Deepfakes of Elon Musk were also commonplace, exploiting footage from prior interviews.

Alongside Quantum AI, the Facebook ads claimed to promote investment opportunities in other cryptocurrencies, energy companies, and government programs.

A manual analysis of the videos also identified glitches that are potential indicators of synthetic voice generation tools, such as different people saying the same words simultaneously or voices changing their accents multiple times in a single sentence. Reverse image searches of thumbnails from some of the videos also revealed source videos with the original audio, before it had been manipulated.

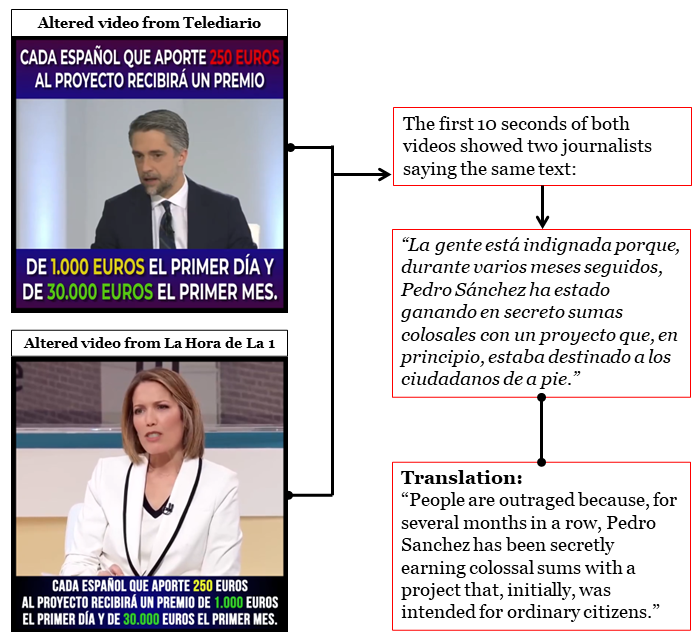

For instance, two fake videos advertised by the page Golden Sprinter contained manipulated footage sourced from old footage of two journalists from Spanish channel TVE interviewing Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez. The first video distributed in three ads on January 8, 2024, used footage that originally appeared on the news program Telediario nearly two years earlier. A reverse image search using Google Lens showed social media accounts sharing clips, screenshots, and quotes of the interview after it first aired on February 28, 2022. The second video, promoted in an ad on January 8, 2024, manipulated interview footage from the program La Hora de La 1 that originally aired on November 30, 2023.

Although the videos contained the same number of words, the duration of both videos had a difference of fifteen seconds due to the silences or pauses introduced in some sections and the alteration of the play speed.

The videos using altered TVE’s interviews also showed similarities with the audio tracks of videos used in ads posted by the pages Enforce a ban and A stable future. According to a search of Meta’s Ads Library, Enforce a ban targeted Meta users in Ecuador, while A stable future aimed to audiences in Peru. (Meta allows ad sponsors to select a target country for their ads, leading to users in the selected country to be the recipients of the ads.) A transcript of the videos showed that they had differences in the number of words: the Spanish-language audio has 536, Ecuador’s 601, and Peru’s 585. The quantity of words differed because of changes on the tenses or expressions, and the localization of the content when mentioning currency, presidents, and names of each country. Despite the variation in the number of words, every sentence implied the same.

In addition, the audio tracks for the videos sponsored by Enforce a Ban and A stable future, showing Ecuador’s Daniel Noboa and Peru’s Dina Boluarte respectively, featured different accents. For instance, in the minute 3:40 of both videos, Noboa says “aquellos” (“those,” in English) with the sound of a single “l,” which would normally be pronounced as a “y” sound. Meanwhile, Boluarte pronounces the letter “c” when saying the number 100,000 (or “cien mil” in Spanish) with a lisped Castilian accent, which is particular to some Spanish regions.

Another inconsistency related to the language appeared in an ad that uses forged audio of an interview with Elon Musk. The ad, promoted by the Facebook page Capital Crest, reproduced the audio in the Spanish language. However, at the end of the video the voice changes from Spanish to English when Musk is seen saying the name of the car – “Tesla Model 3” – that Musk would supposedly give as a reward to the investors.

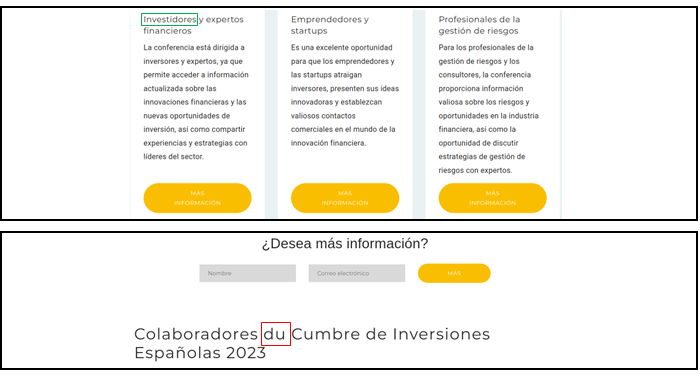

The content of the websites targeting Spanish-speaking audiences and hyperlinked to the ads also showed some evidence that the operators did not have sufficient knowledge of the Spanish language and could have used translation tools, such as AI-based translation services, leaving some inaccuracies. For instance, websites targeting Ecuador mistakenly used the translation of the word “speaker,” which in Spanish has several meanings: a device used to broadcast sound (“altavoz” in Spanish) or a person who speaks to an audience (“ponente” or “conferencista”). The text on the website referred to a device instead of a person.

Websites targeting Spain also included words in other languages, such as “investidores” (Portuguese for “investors”) and “du” (“of” in French).

As shown in the image above, the screenshot in the bottom also shows a form that appeared on all of the destination websites (that the Meta ads pointed to) with two boxes that ask for a name and email. This is the form that was mentioned in the videos for people to fill out in order to be contacted by a supposed “consultant” or “specialist.”

Anonymous coordination

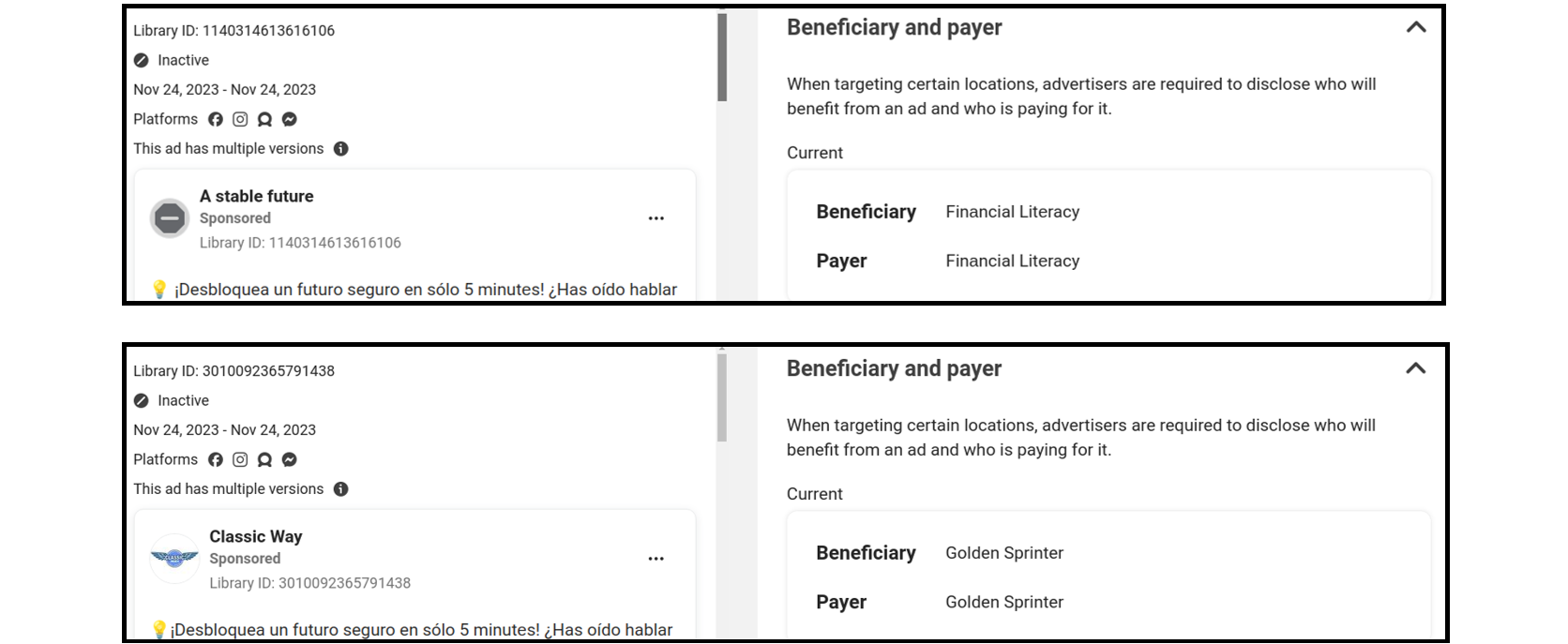

The DFRLab could not find evidence about those behind the Meta ads nor the websites. Although ads targeting European countries about politics and social issues (such as the videos that showed presidents and candidates) must include certain data about the advertisers under EU law, the operators included false information such as random characters for the beneficiary and payer field. The public WhoIs databases that contain domains registration data also showed that the entities used domain privacy’s service of a URL acquisition company NAMECHEAP INC, which allowed the owners to hide their identity.

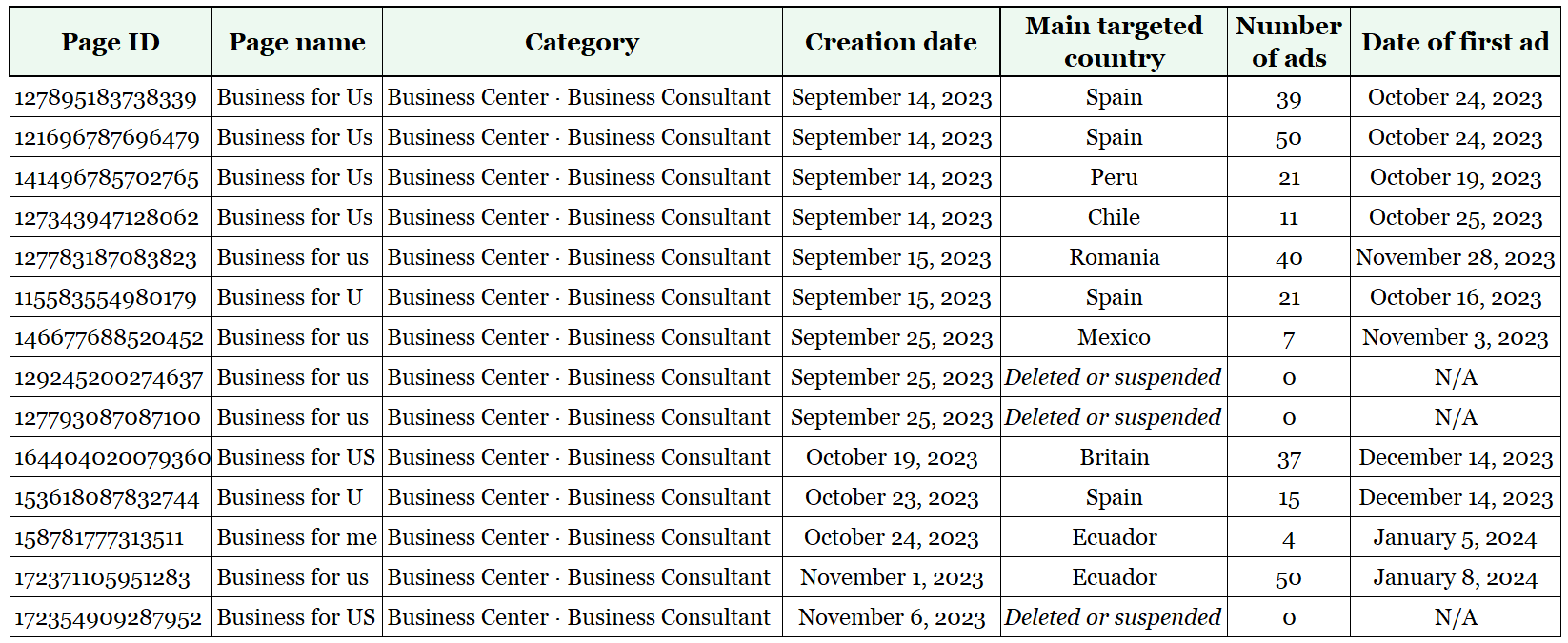

The data collected from the Facebook pages, Meta’s ads, and WhoIs databases showed that the owners successfully kept their anonymity with fake or restricted information but confirmed that clusters of accounts and websites operated in a coordinated manner. For instance, fourteen pages with names starting with the word “Business” were created on the same day or week, initiated the paid campaigns within a similar date range, and chose “Business Center · Business Consultant” as their categorical classification.

The pages also posted in their Home sections the same photos pulled from elsewhere online, most of which originally appeared in stock image services or in previous publications.

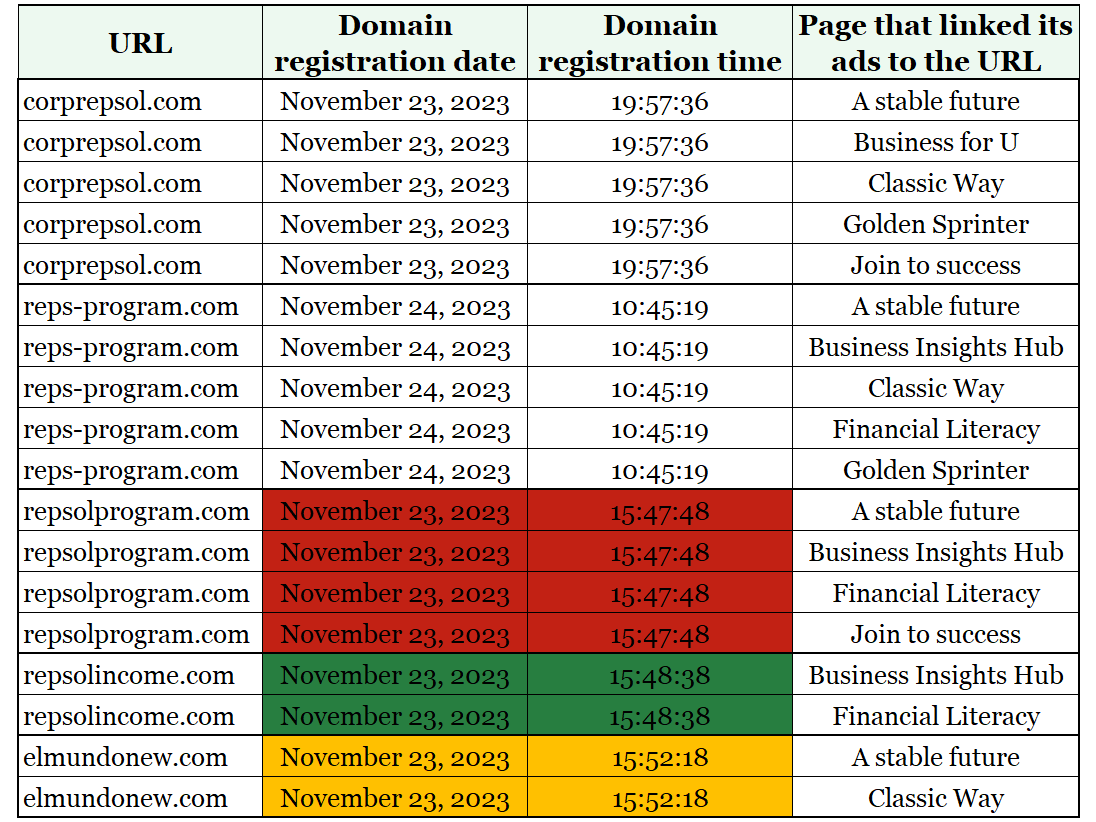

A small subset of the pages – Classic Way, Finаncial Litеracy, Golden Sprinter, Business Insights Hub, Join to success, and A stable future – posted ads that linked to the same URLs. Some of these destination domains were registered within the same day or even hour. Given the breadth of languages used, the advertisers appeared to have targeted audiences in Australia, Mexico, Peru, Spain, and another twenty countries in Europe and Latin America.

In addition, the Facebook pages A stable future and Classic Way registered as beneficiaries or payers of their ads the names of other Facebook pages, such as Financial Literacy and Golden Sprinter, that also distributed the ads determined to scam recipients.

The DFRLab performed the above research manually out of a lack of trustworthy tools that can accurately and specifically identify the use of deepfakes. As such, the use and development of open-source tools that allow a more in-depth and automated analysis of deepfakes could help authorities, governments, and researchers to detect, expose, and interrupt in time the expansion of those who try to deceive internet users, and, as in this case, commit crimes globally. However, analyses that combine open-source tools and platform transparency measures are still useful to detect the footprints left by these online malicious operations.

Cite this case study:

Daniel Suárez Pérez, “Spanish-language ads amplify scams using audio deepfakes of public figures,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), June 6, 2024, https://dfrlab.org/2024/06/06/spanish-language-ads-amplify-scams-using-audio-deepfakes-of-public-figures/.