In Sub-Saharan Africa, China embraces Russian messaging against Ukraine

Russian narratives thrive in Sub-Saharan Africa with the help of Chinese media networks, localization expertise, and infrastructure

In Sub-Saharan Africa, China embraces Russian messaging against Ukraine

Share this story

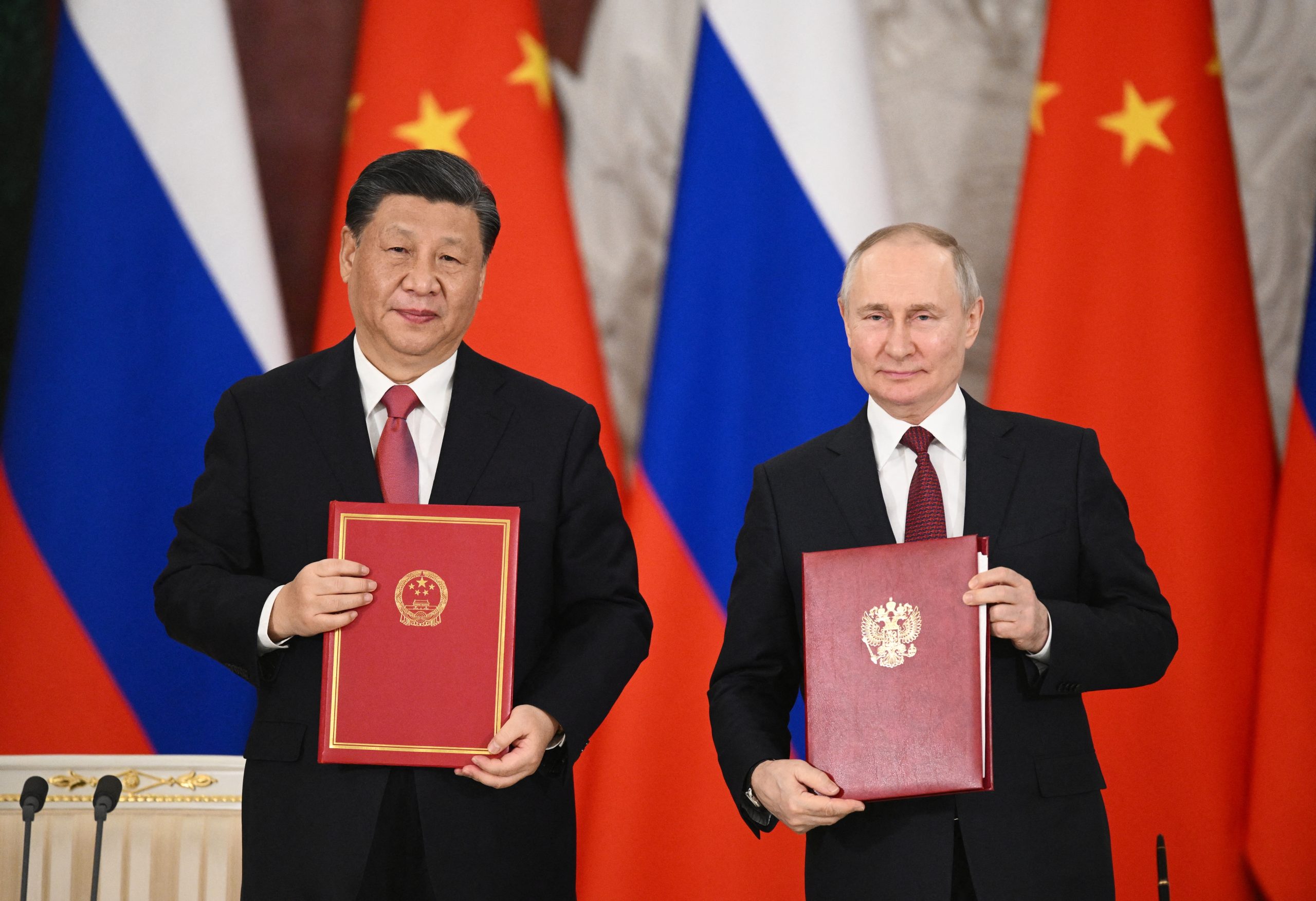

BANNER: Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping attend a signing ceremony at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia March 21, 2023. (Source: Sputnik/Vladimir Astapkovich/Kremlin via Reuters)

Over the last several years, China has pushed pro-Russian narratives regarding Ukraine in sub-Saharan Africa through its content-sharing platforms, China-aligned commentators, social media presence, and broadcasting infrastructure. These influence operations aimed to undermine NATO’s support for Ukraine and US influence in the region.

Even before Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, China and Russia were strengthening their media cooperation across Africa as they both sought to challenge Western media’s international dominance. China has done so by establishing content-sharing agreements leading those participating African media outlets to easily disseminate Chinese state media reporting, including amplifying Russian talking points around Ukraine. China has cultivated African commentators whose viewpoints demonstrate support for Chinese initiatives in global majority countries, lending credibility to Russia’s disinformation around the war. Chinese social media accounts and television service providers supply alternate means for Russian narratives and programming to reach African audiences, helping Russian media outlets evade platform bans and sanctions.

In principle, Beijing champions non-interference in the sovereignty of other countries. So once Russia launched its war, China maintained official neutrality and called for a peaceful settlement. “The sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries should be respected and protected,” proclaimed Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. Then in March 2022, China abstained from a United Nations resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The actions of Chinese media reveal China’s true stance. Chinese outlets copy the terminology Russia uses to obfuscate its belligerence in Ukraine, for example by preferring “special military operation” over “invasion” and “war.” Chinese state media amplified pro-Russian narratives, including those claiming that NATO’s eastward expansion forced Russia to invade; the United States funded labs in Ukraine for biological warfare; the Bucha massacre was staged; the United States blew up Nord Stream; and more. Its misleading and distorted coverage of Russia’s invasion effectively exposes Beijing’s support for the Kremlin.

China’s amplification of Russian narratives is based on the need of both countries to strengthen their relatively weak voices abroad. It believes it is deficient in “discourse power,” the ability to shape the international agenda to advance its values and interests. Since China perceives the West as at the forefront of global agenda-setting power, it works with like-minded partners to jointly strengthen their voices, oppose Western influence, and promote a multipolar world order. Russia shares these insecurities and aspirations, drawing Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping closer together.

At the launch of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, twenty days before Russia invaded Ukraine, their relationship culminated in a “no limits” partnership. During their subsequent meeting in September 2022, Putin expressed admiration at the “balanced position of [his] Chinese friends when it comes to the Ukraine crisis,” adding that US attempts to restore unipolarity would fail. To pursue “a more just and democratic multipolar world order,” the leaders announced a suite of strategic collaborations in March 2023, encouraging further media, think tanks, and publishing exchanges. The two countries released similar statements about multipolarity and media collaboration during Putin’s reciprocal visit to China in May 2024.

Encouraged by their leaders, Chinese and Russian media have collaborated to challenge Western media’s portrayal of their countries, thereby extending their messaging to global majority countries. After the leadership meeting between Xi and Putin on March 2023, the Chinese propaganda department and China Media Group (CMG) officials met with Russian state media representatives from Rossiyskaya Gazeta, Sputnik, and RT to discuss “the role of media in strengthening a multipolar world.” Following the 2024 Putin-Xi meeting, Gazprom-Media and CMG signed a memorandum to cooperate on artifical intelligence (AI) development for media generation.

In June 2023, at the Vladivostok Media Summit, the Chinese consul general of Vladivostok said that leading Western media “create a wrong image of China and Russia.” She proposed that the two countries “should unite, to create a true image of a partner country, and then work together to reverse Western media’s domination.” In September 2023, news executives of both countries reflected on the work they have achieved in the past year in supporting one other in the media on issues involving their “core interests,” a nod toward the invasion.

In addition to bilateral agreements, Chinese and Russian media have also been expanding in Africa. A prominent group for promoting cooperation is the multilateral BRICS (named after Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) group, which expanded in January 2024 also to include Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and Iran. Following the annual BRICS leadership summit in 2023, BRICS hosted its 6th BRICS Media Forum for the media outlets of member countries in Johannesburg centered around media cooperation with Africa.

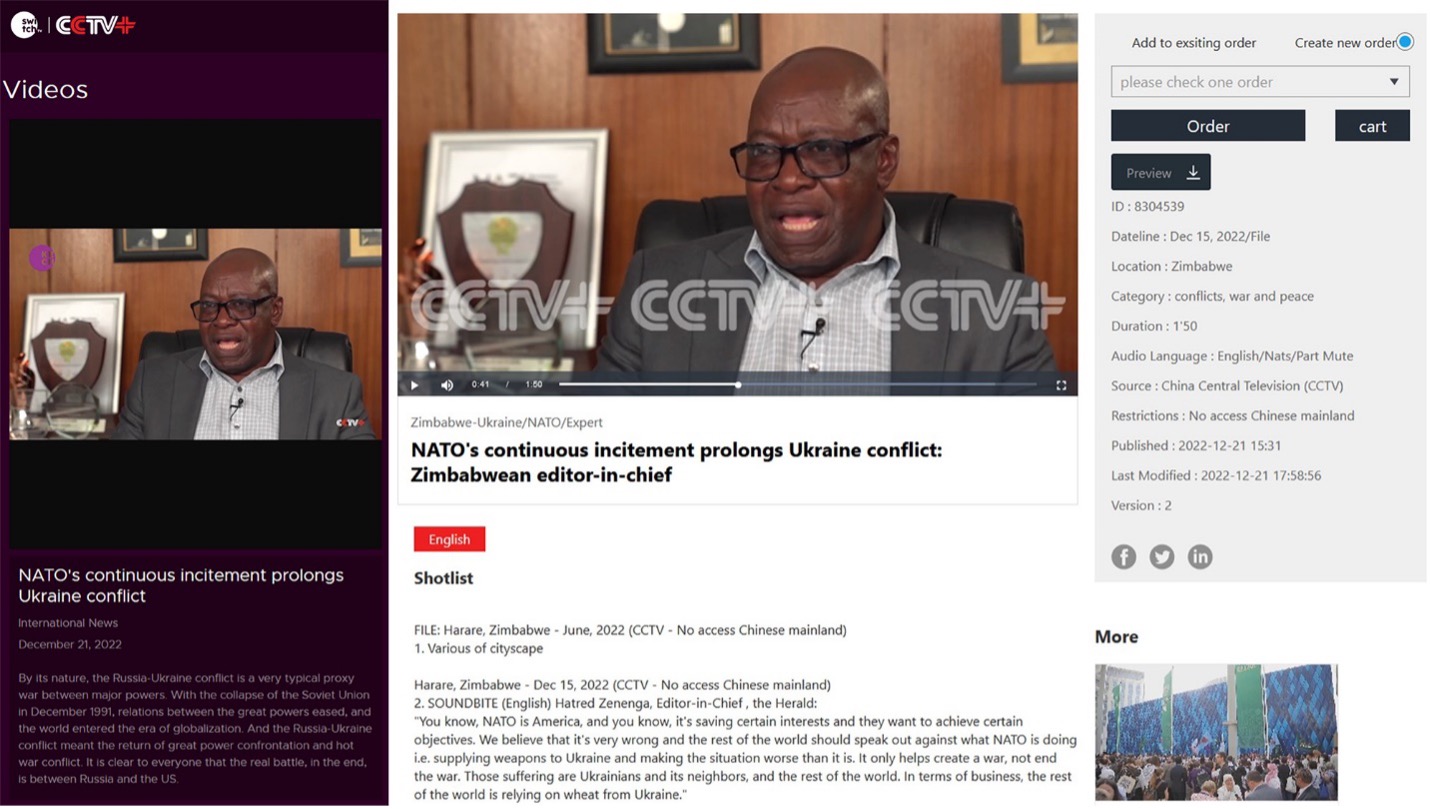

In Sub-Saharan Africa, China has already built media relationships through content-sharing agreements and regional exchanges. To disseminate China’s worldview, CMG runs a media distribution platform on CCTV+’s homepage that provides international news channels access to original CCTV-produced multimedia. CMG launched another content-sharing platform for CGTN content, the “All Media Service Platform” (AMSP), in February 2022 to enhance sharing of Chinese content following the Winter Olympics. As of May 2024, CCTV+ has 357,000 and AMSP has nearly 64,000 media files that are easily searchable and downloadable. Among these are news clips that push familiar pro-Russian narratives around Ukraine. In 2018, CMG formed a group called the Africa Link Union (ALU), granting access to CCTV+’s platform to at least thirty-five African news agencies as of late 2020.

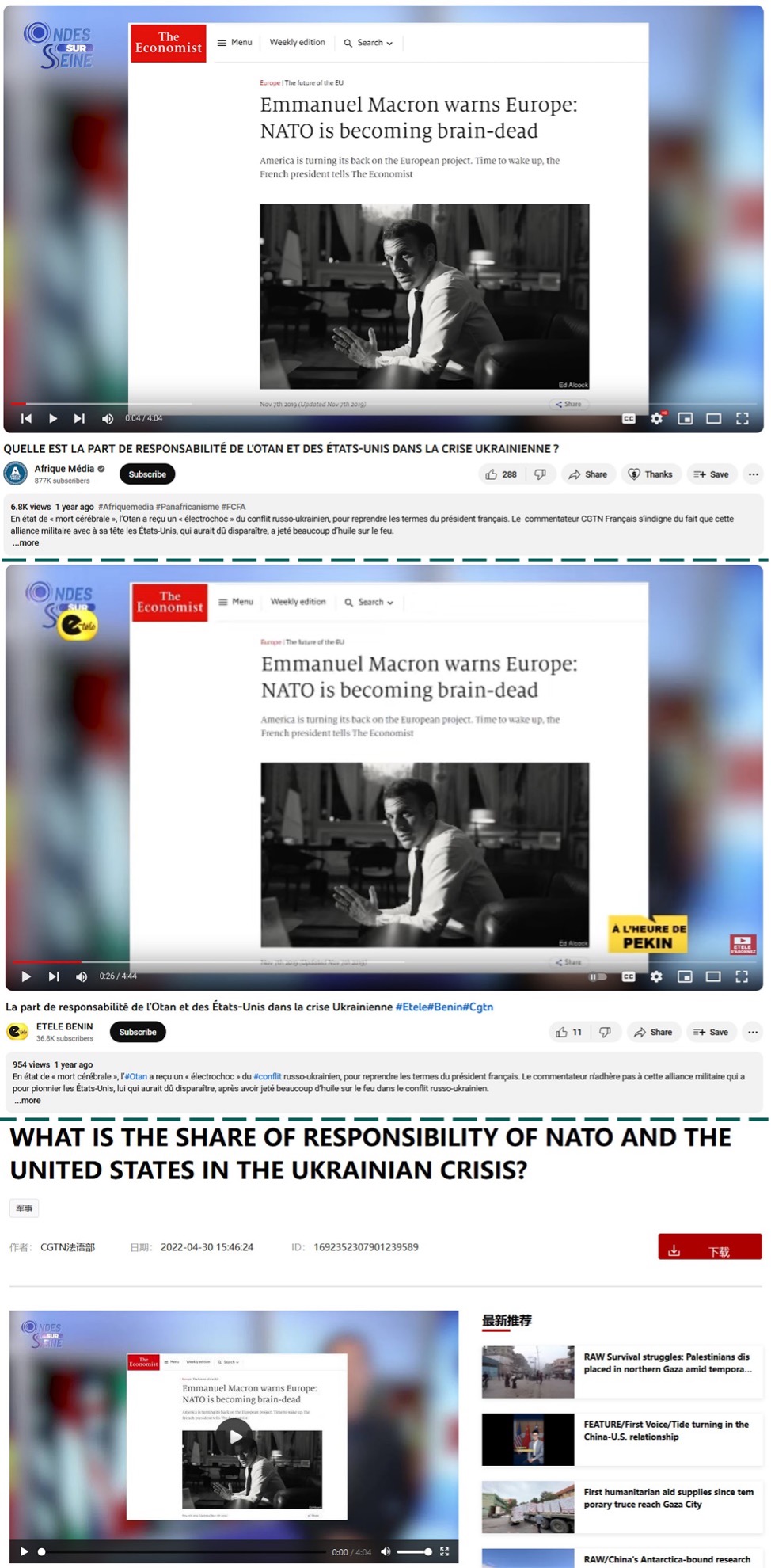

There are multiple instances of ALU-participating news outlets publishing pro-Russian videos regarding the war in Ukraine from these two CMG content-sharing platforms to their African audience. In one case, Kenyan ALU member Switch TV broadcasted an interview from the CCTV+ platform in which the editor-in-chief of the Zimbabwean newspaper the Herald, a publication known to spread pro-China messaging, blamed NATO for prolonging the war. In another instance, CCTV+ partnered with Cameroonian news agency Afrique Média TV (AM-TV) in 2020. AM-TV has links to the Wagner Group and its disinformation and election interference. Praising AMSP, AM-TV’s CEO said his group has “learned from” and “adapted new working methods” from CMG. AM-TV and another ALU member, Etélé of Benin, have directly used an AMSP media asset that also criticizes NATO’s military support of Ukraine.

African news media’s adaption of Chinese content-sharing platforms has inspired Russia to propose a joint initiative, reflecting China’s lead in media infrastructure. Only a decade ago, in 2014, China was learning global influence strategies from Russia. In an article titled “What Can We Learn From ‘Russia Today?,’” Chinese outlet People’s Daily praised RT as the “foreign propaganda aircraft carrier that makes the West tremble” that capitalized on social media to sway those considered “easily influenced”: young people and non-Westerners. Now drawing from China’s presence in Africa, at the 2023 BRICS Media Forum, Dmitry Gornostaev, deputy editor-in-chief of Rossiya Segodnya (Sputnik’s parent company), proposed a media initiative modeled on an existing content-sharing agreement between Xinhua and South Africa’s African News Agency. The resulting content-sharing platform between leading BRICS media would provide Africans with news “not tainted by narratives and fakes of the West” and ensure that they learn about Russia from Russian journalists.

The last large joint media infrastructure project between China and Russia was in 2017, when a Chinese company developed an app, Russia-China: The Essentials, for their domestic users. Given Chinese expertise in web infrastructure, Gornostaev’s envisioned platform would likely be built on the foundations of CCTV+ and AMSP but with the additional offering of Russian content. If this centralization of content-sharing between China and Russia occurs, it may result in a wider spread of Chinese and Russian narratives among partnered news media in Sub-Saharan Africa.

To demonstrate support from global majority countries for Beijing’s vision and policies, Chinese state media cultivate and amplify aligned African voices. At the 2023 BRICS Media Forum, Xinhua quoted “Africa-China Review” (非中评论), a Rwanda-based news website. To contrast the prejudices of Western media in Africa with the sincerity of BRICS media, Africa-China Review said that biased Western media ignore facts, always portraying Africa as ridden with “hunger, poverty, disease, war, AIDS, and so on.”

Many of Africa-China Review’s articles read like news from the mainland, with titles like “China’s CPC Serves the People Wholeheartedly” and “China’s Whole Process People’s Democracy Brings Better Life for All Citizens.” Its X account shares and likes posts primarily by Chinese state media and diplomatic accounts. Its founder and editor-in-chief, Gerald Mbanda, regularly pens articles for China Daily and Xinhua. Most importantly, only Chinese state media extensively quote Africa-China Review, citing its praise of China’s economic, COVID-19, and governance policies and initiatives in Africa. On Ukraine, Africa-China Review accused the United States of being the “prime suspect” for the Nord Stream explosion and escalating the conflict while promoting China’s peace position. This publication amplifies Chinese narratives as views shared by Africans and contributes to the spread of Russian narratives.

Not limited to journalists, a South African student leader who shared pro-Russian narratives was also extensively quoted by Chinese state media. Journalist Lili Pike found that Deputy President of the South African Students Congress (SASCO) Buyile Matiwane wrote an article on South African news website IOL pushing the conspiracy theory purporting US bioweapon laboratories in Ukraine. Chinese state media then quoted Matiwane, emphasizing his position as a South African student leader to their global readers. In the past, Matiwane has written articles defending China’s claim on Taiwan and Chinese democracy. The Chinese embassy in South Africa sponsored visits to China for student leaders of SASCO, including Matiwane, as part of a learning exchange in 2019; similar visitation programs for journalists have resulted in China-friendly articles upon return.

IOL’s leadership vowed to combat disinformation while hosting disinformation and permitting the use of biased Chinese reporting about Ukraine to its readers. South African businessman Iqbal Survé owns the majority share of the publication through an intermediary investment company. Survé represented IOL at the 2023 BRICS Media Forum. Addressing the forum’s theme, “BRICS and Africa: Strengthening Media Dialogue for a Shared and Unbiased Future,” he encouraged members to collaborate with Africa and urged members to “actively exchange best practices in countering disinformation.” Yet, rather than countering disinformation, his publication has also published disinformation on Ukraine. IOL’s republishing of Chinese news is a contributing factor, as it has a content-sharing agreement with Xinhua and is partly Chinese-owned. Dani Madrid-Morales, a disinformation researcher at the University of Sheffield, found that at the start of the war, 75 percent of IOL’s articles about Ukraine were reposted from Xinhua, which framed the war largely around economics rather than humanitarian suffering.

Chinese media infrastructure and distribution allowed RT to circumvent EU sanctions in Sub-Saharan Africa. The EU sanctioned several “Kremin-backed disinformation outlets” to end their broadcasting of manipulated information soon after the invasion. Because of the sanctions, MultiChoice Group Ltd, the biggest pay-TV provider in Africa, ended the direct distribution of RT and its content. Unaffected by the EU policy, Chinese television distributor StarTimes continues to broadcast RT in more than thirty countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, a de facto circumvention of the sanctions. Chinese media distribution is further expanding via the ongoing cooperation project, “Access to Satellite TV for 10,000 African Villages” (“万村通”), which Xi announced in 2015, that provides digital television services to about 16 million users in Sub-Saharan Africa under the auspices of StarTimes. Facing media sanctions, Russia benefits from China’s extensive media capabilities in Africa, allowing Russia to disseminate its anti-Ukrainian narratives by proxy.

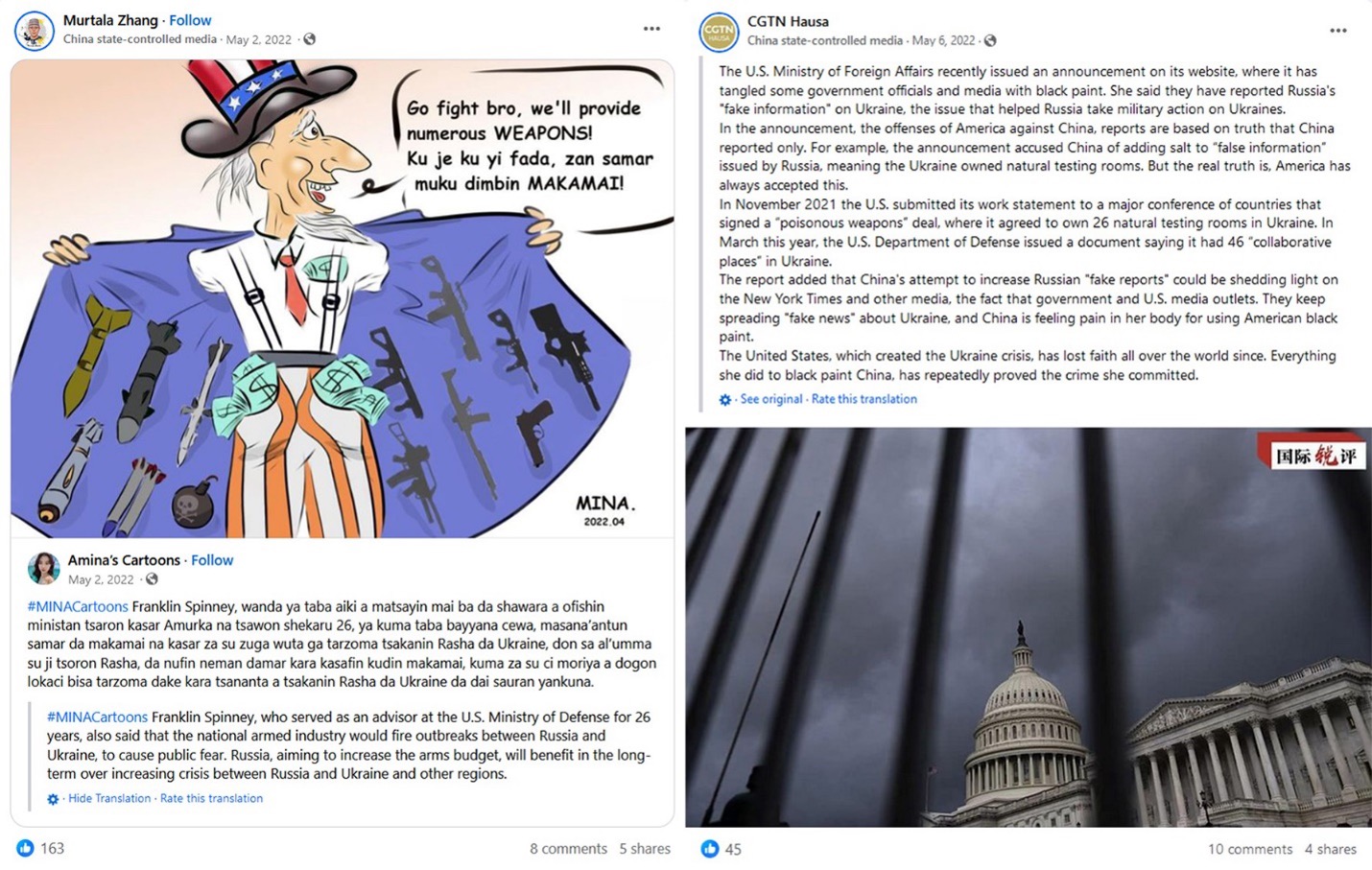

On social media, Chinese state media pages have also been spreading pro-Russian narratives to Africans. A narrative that specifically involves Africa regards the March 2022 UN resolution to condemn Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, in which African countries were divided in the voting. Practicing “precise communication,” the tailoring of messaging content for a particular audience, Chinese Facebook pages claimed that the West was trying to force Africa out of its “neutrality.” Furthermore, CGTN Hausa and CGTN Français amplified CGTN-produced documentaries, “The Spreading Shadow” and “The Business of War,” both of which decry US military support for Ukraine.

Chinese state media’s improving ability to localize content is exemplified by influential China Radio International (CRI) reporter Murtala Zhang, who communicates fluently in Hausa to a Nigerian audience on Facebook, where he has 1.2 million followers. For example, he authored an article in Hausa defending China from accusations that it repeats Russian disinformation and doubling down on the biolab conspiracy theory.

Contributing to the ongoing information war launched by Russia around its invasion of Ukraine, China disseminates and amplifies Russian narratives to its global audience, prevalent with narratives opposing NATO and disinformation incriminating the United States. To develop discourse power and counter Western media in Sub-Saharan Africa, China has partnered with Russia through bilateral agreements and BRICS initiatives. Chinese content-sharing agreements and platforms gave African news media access to source Chinese reporting featuring pro-Russian narratives, especially in distorting the coverage of Ukraine. China has cultivated and amplified aligned local voices to show African endorsement of Chinese policies and by extension Russian disinformation. Chinese media infrastructure has allowed RT to evade EU sanctions, facilitating the uninterrupted broadcast of Russian propaganda to Sub-Saharan Africans. To spread narratives of Ukraine on social media, China has localized its messaging in Sub-Saharan Africa. As Chinese and Russian media cooperation progresses and evolves, the consolidation of their capabilities, especially through content-sharing platforms, may further erode accountable reporting and weaken solidarity for Ukraine in global majority countries.

Cite this case study:

“In Sub-Saharan Africa, China embraces Russian messaging against Ukraine,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), June 12, 2024, https://dfrlab.org/2024/06/12/china-russia-sub-saharan-africa/.