Banned, yet broadcasting: Sanctioned Belarusian state media influencing the Polish elections

Belarusian state media uses digital platforms to promote candidates and shape narratives within Poland ahead of the 2025 presidential elections.

Banned, yet broadcasting: Sanctioned Belarusian state media influencing the Polish elections

Share this story

BANNER: A person votes at a polling station during presidential elections in Warsaw, Poland, on May 18, 2025. (Source: Aleksander Kalka/NurPhoto via Reuters)

Executive summary

Belarusian state media is spreading disinformation targeting Polish audiences on platforms including TikTok, YouTube, X, and Facebook, actively circumventing European Union (EU) sanctions.

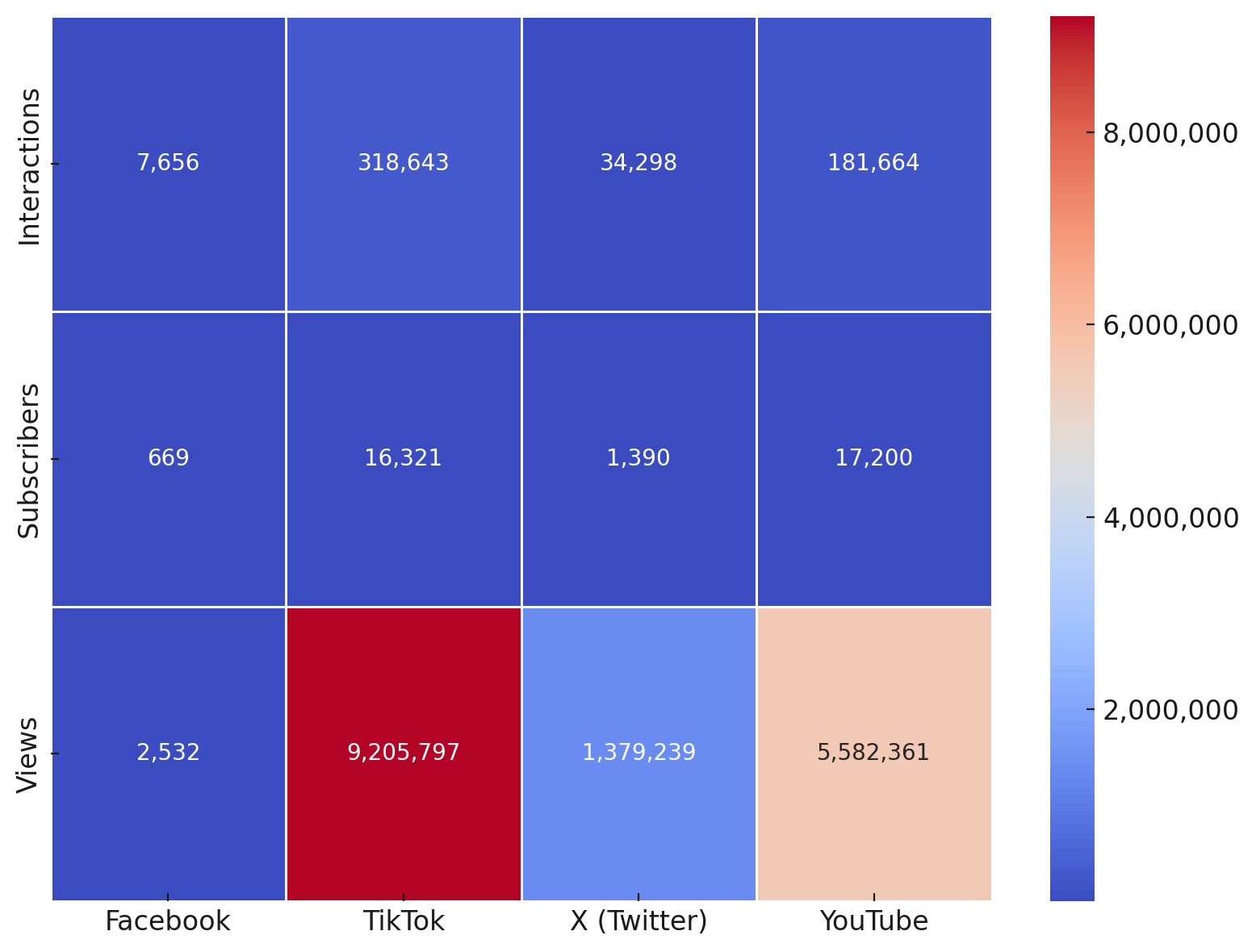

As of May 7, TikTok, YouTube, X, and Facebook accounts associated with the state-owned Polish-language edition of Radio Belarus, which is part of the sanctioned entity Beltelradio, had published over 7,790 videos and posts, with 16 million views and at least 542,000 engagements.

With millions of views and high engagement, Radio Belarus is effectively conducting a digital campaign to influence Poland’s 2025 presidential elections, representing a case of foreign interference from a sanctioned entity. The content seeks to undermine public trust in Poland’s democratic institutions, amplifies socially polarizing narratives, and opts to either discredit or promote specific political candidates.

The platforms, which are obligated under the Digital Services Act (DSA) to prevent sanctioned content from reaching EU audiences, were informed, by a subset of the authors, about these sanctioned channels in December 2024. Despite the notice, throughout the course of the Polish election campaign, the sanctioned channels were still accessible via European IP addresses, indicating a lack of action from the platforms. In the final week leading to the first round of the Polish presidential elections, the case was once again flagged to the platforms by a subset of the authors. TikTok was the only platform to act, according to our review, applying a geofence around the content. Platforms have an obligation under Articles 34 and 35 of the DSA to assess and address systemic risks towards the integrity of the elections and illegal content on their platforms.

Background

In December 2024, Radio Belarus was flagged through a report by Science Feedback and Alliance4Europe to all DSA-designated Very Large Online Platforms as still being accessible to EU audiences, in violation of EU sanctions. In the context of the Polish elections, the Polish-language edition of Radio Belarus has discredited the legitimacy of the elections and amplified two particular candidates via repeated interviews: Maciej Maciak (who received enough signatures to qualify as a candidate) and Aldona Skirgiełło (who failed to receive enough signatures).

The social media platforms have a legally mandated obligation under the DSA to prevent EU audiences from being exposed to illegal content, such as content originating from sanctioned entities. Platforms also have an obligation under the DSA Articles 34 and 35 to mitigate election-related systemic risks. An audit conducted using various European IP addresses found that Radio Belarus’s content remained accessible throughout the election period, except for TikTok’s geofencing measures, which were implemented less than a week before the first round of voting.

The narratives promoted by Radio Belarus suggested that the legitimacy of the Polish elections was compromised, with particular emphasis on the lack of independence of the Supreme Court, which determines the validity of the election. Claims have also been made about the lack of independence of the National Electoral Commission. For example, one Radio Belarus video included Maciak stating that the Electoral Commission was influenced by external actors, which he suggested affected the process surrounding his candidacy registration. There were also numerous claims about media bias undermining the fairness and legitimacy of the election.

Sanctioned but thriving

On June 3, 2022, the EU adopted its sixth sanctions package against Belarus, which included state-owned Belteleradio, which owns Belarus Radio. The state-owned broadcaster was identified as a primary instrument of state propaganda in Belarus, and sanctions were imposed as part of the EU’s broader response to human rights violations and the suppression of democratic processes in the country. The sanctions against Belteleradio included an asset freeze and the prohibition on making funds or economic resources available, which effectively prohibited any commercial or financial engagement with Belteleradio from within the EU.

The ban on providing economic resources also covered offering internet services, satellite access, content hosting, or any other tools that could help these entities earn money. The Commission clarified that it considers hosting and broadcasting as an “economic resource.” These restrictions aimed to limit the broadcaster’s operations within the EU and block access to supportive resources. As a result, sharing content from Beltelradio on platforms like YouTube, Facebook, X, and TikTok within the EU would be considered a violation of these sanctions.

Despite EU sanctions targeting Belarusian state media, Radio Belarus was able to escalate its digital influence campaign targeting Polish-language audiences by leveraging platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, X, and Facebook. The outlet used these popular platforms to promote manipulated narratives within the Polish infosphere.

In August and September 2023, Radio Belarus launched a Polish-language YouTube channel, followed by a Polish-language Telegram channel, and accounts on X and TikTok. Radio Belarus began creating Polish language assets three weeks before the October 2023 Polish parliamentary elections. Valery Radutsky, director of International Radio Belarus, openly linked the new Polish-language programming to Poland’s parliamentary elections, stating that the program would cover how public opinion in Poland was manipulated during elections and criticisms of Poland’s ruling party.

In October 2023, Radio Belarus introduced a new talk show called Thoughts about Poland, which was, according to the authors of the show, intended to address what they claimed was a lack of awareness among Polish citizens about the true state of their country. According to Anton Vasyukevich, general producer of Belarusian Radio, since Belarusian media outlets were blocked in Poland, Radio Belarus aimed to use popular platforms accessible to Polish audiences to share its content in Poland.

The launch of Polish-language social media channels by Radio Belarus increased its ability to disseminate hostile and manipulative narratives into the Polish information sphere, and doing so right before Polish elections indicates an intent to influence public sentiment during a critical political event in the country.

The Digital Services Act

The European Commission has unambiguously stated that hosting content from sanctioned media entities is prohibited. Under the DSA, platforms must act on manifestly illegal content when it is signaled to them (DSA recital 22).

Secondly, at a more systemic level, platforms have to ensure that they take appropriate measures to mitigate the risks posed to European audiences (DSA Articles 34 and 35). The widespread nature of the issue and platforms’ apparent failure to act on the problem, despite being notified, potentially means that the platforms will have failed to fulfill their obligations under Articles 34 and 35 of the DSA.

This investigation indicates that Radio Belarus expanded its presence on these platforms since 2023 and made attempts to target the 2025 Polish presidential elections. The analysis revealed that Radio Belarus does not merely aim to inform, but also seeks to discredit the legitimacy of the election process and promote or discredit certain candidates. Radio Belarus placed particular emphasis on highlighting the candidates Maciak and Skirgiełło, with seven videos conducted with the former and three with the latter.

In view of this, the activities of the sanctioned Belarusian state-controlled media organization Radio Belarus could be qualified as foreign interference. Radio Belarus employed a series of manipulative techniques, examined in this report using the DISARM Framework, a standardized taxonomy used to codify the tactics and techniques used by information manipulators to pollute the information space.

Platform-driven outreach by Radio Belarus into the Polish infosphere

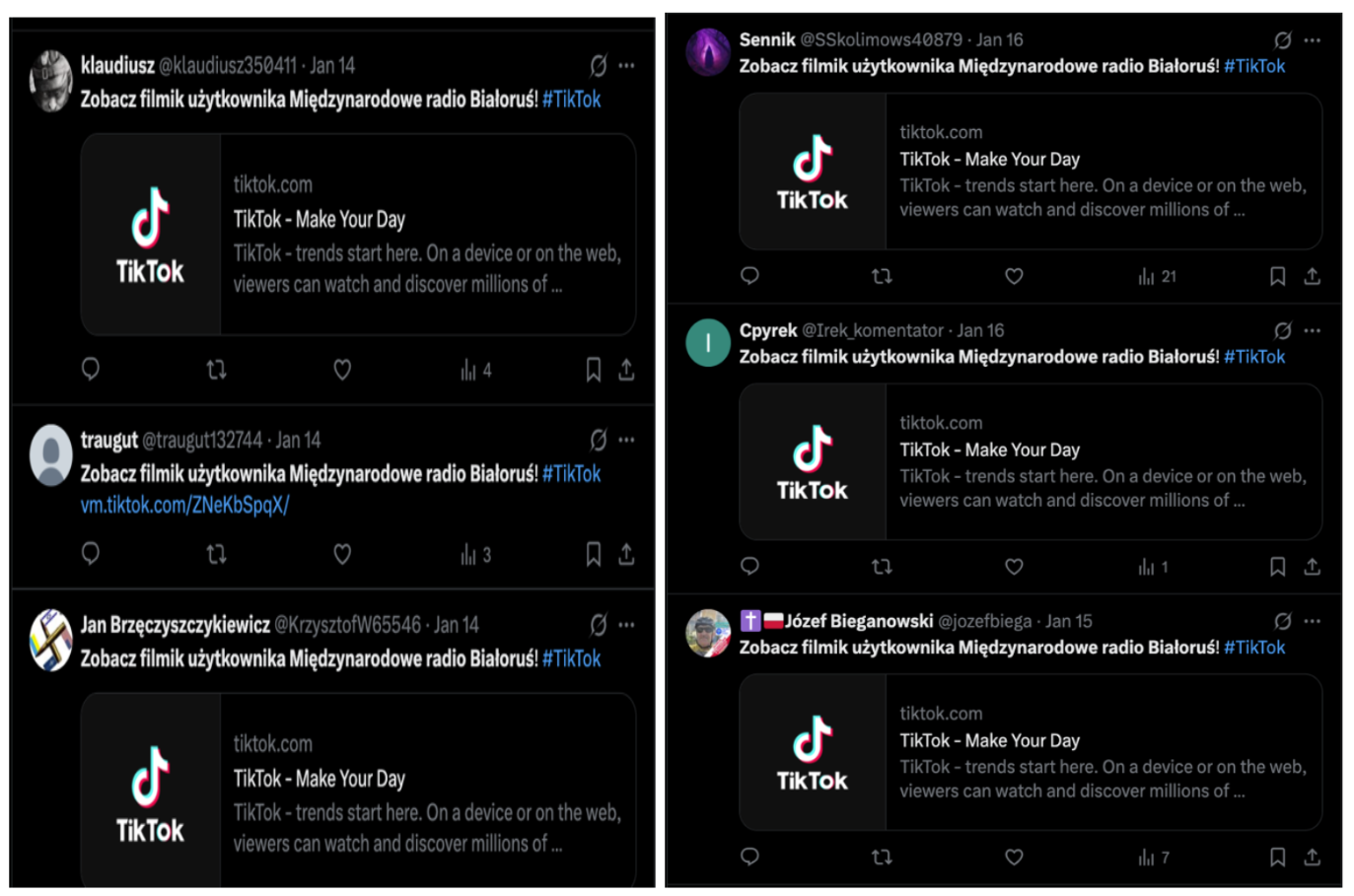

Radio Belarus published its first TikTok video in September 2023. As of May 7, 2025, the account had shared over 930 videos, which collectively garnered more than 9.2 million views and around 320,000 engagements. The account had over 16,000 followers at the time of writing. According to the social media analysis tool Exolyt, approximately 84 percent of these followers were based in Poland, while only 3 percent were located in Belarus. In 2025 alone, Radio Belarus published over 230 TikTok videos, which received nearly two million views. The authors also identified cases where Radio Belarus TikTok videos were shared by seemingly inauthentic X accounts that promoted the clips using an identical phrase, “Zobacz filmik użytkownika Międzynarodowe radio Białoruś!” (“Watch the video of the user International Radio Belarus in English”). As of May 7, we found sixty-two tweets reposting content from the Radio Belarus TikTok account, but the activity was not only focused on Radio Belarus as the accounts also reposted political content from other TikTok users.

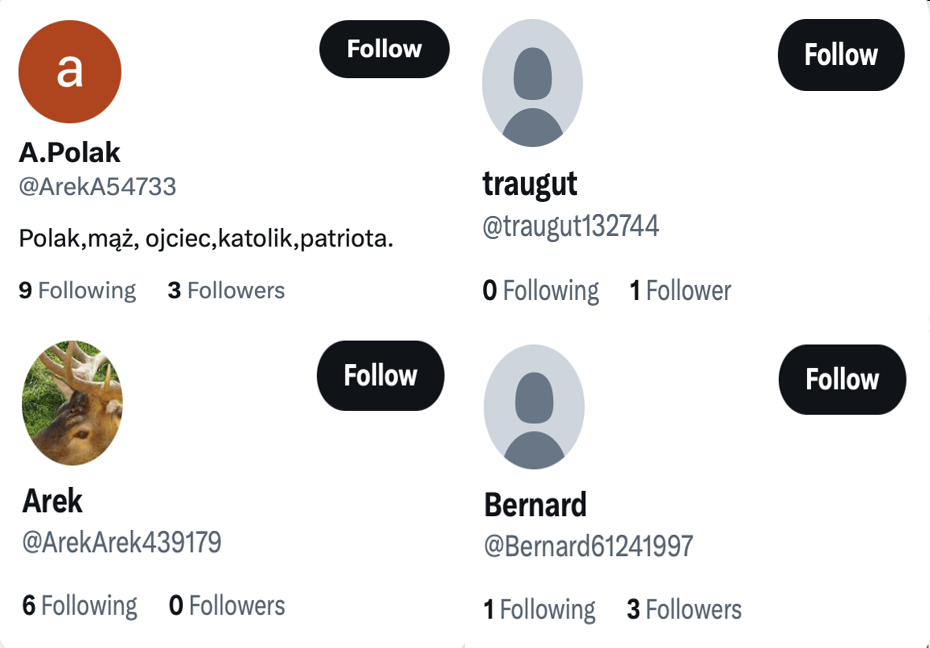

Some of the accounts sharing Radio Belarus videos from TikTok exhibited signs indicating they may be bots, such as a lack of avatar images, suspicious alphanumeric handles, high posting activity, very low follower counts, and no biographies or personal information.

Since December 2023, Radio Belarus has published over three thousand posts on X, which have collectively garnered more than 1.3 million views, despite the account having only 1,390 followers as of May 7. These posts generated over 34,000 engagements. According to the social media analytics tool Meltwater Explore, Radio Belarus’s posts were retweeted over 8,500 times in total. More than 1,900 of those reposts came from accounts in Poland, generating over 500,000 views.

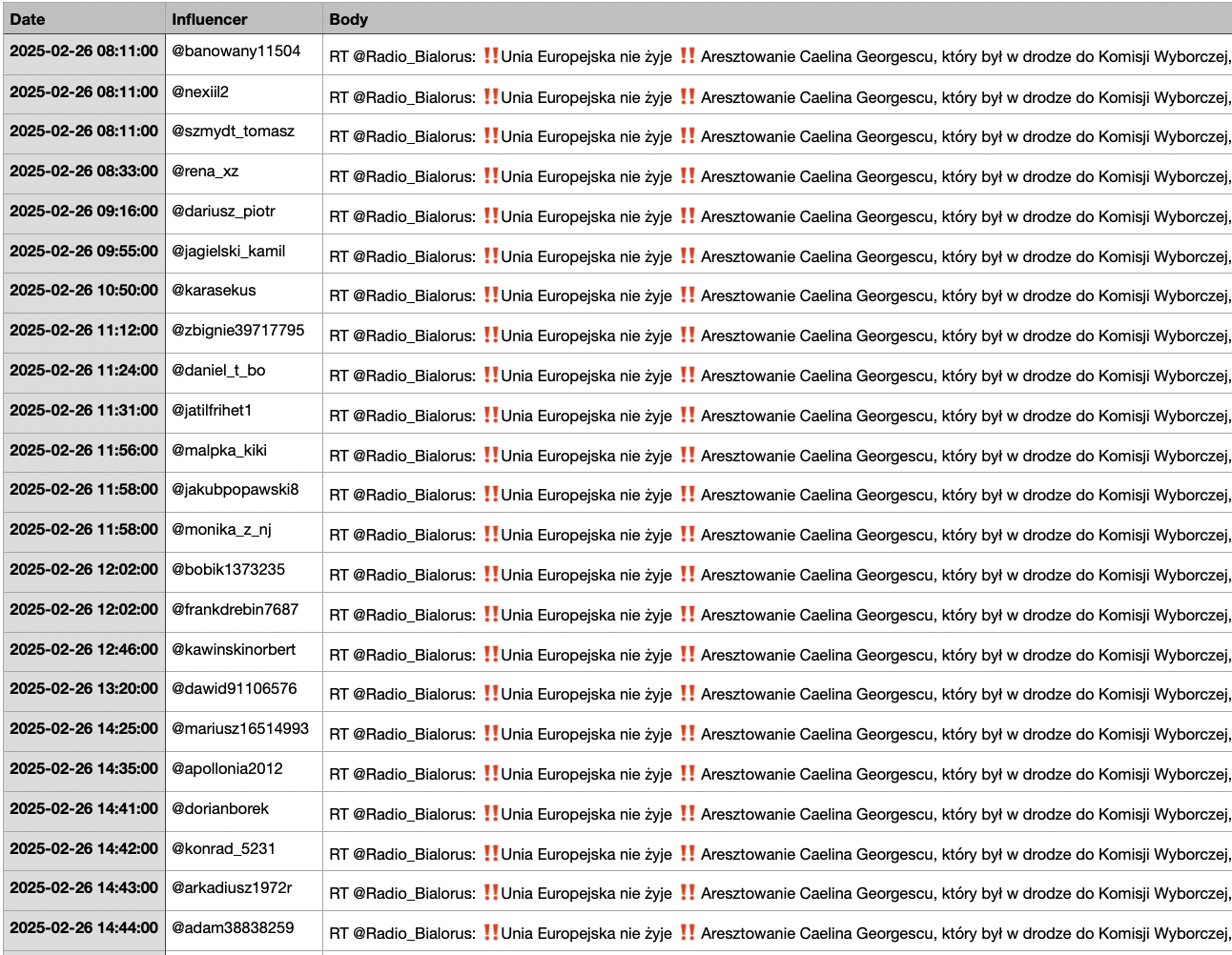

Among the content retweeted by the Radio Belarus X account was a post that was retweeted 128 times precisely on the whole minute mark (e.g. 08:11:00, 15:56:00). This may suggest that the posts were scheduled, as automated tools often execute commands at the start of each minute. This sharing pattern supports the idea of coordinated automation. One post claimed that the arrest of Calin Georgescu, whose Romania’s 2024 presidential election victory was annulled due to evidence of foreign interference, meant “the defeat of the European Union and its de facto death.” As of May 2, this post was retweeted over four hundred times.

Since September 2023, Radio Belarus has published over 1,760 posts on Facebook, generating 7,656 interactions as of May 7, including over 372 shares – primarily within Polish-language Facebook groups. The page also garnered over 2,500 video views.

On YouTube, the Radio Belarus channel published over 2,100 videos as of May 7, amassing over 5.5 million views. A sample analysis of 375 YouTube videos retrieved from the social media listening tool BuzzSumo found that the channel had received over 36,000 comments and more than 124,000 likes on the videos.

Radio Belarus appears to operate a tiered content distribution strategy, where different platforms serve complementary functions in promoting its content. The analysis showed that TikTok is currently Radio Belarus’s most successful and strategically active platform, where it has relatively higher reach, especially among Polish-speaking audiences. YouTube is another high-performing platform for Radio Belarus, with strong viewer engagement metrics. Despite a small follower base, X posts are disproportionately amplified, particularly among Polish-linked accounts. Facebook appears to have the lowest reach and engagement. The objective of the operation appears to be undermining the legitimacy of the Polish electoral system (T0139.001: Discourage) and cultivating support for candidates that align with Belarus’s interests (T0136.005: Cultivate Support for Initiative).

Translating content from Polish to Russian and back again

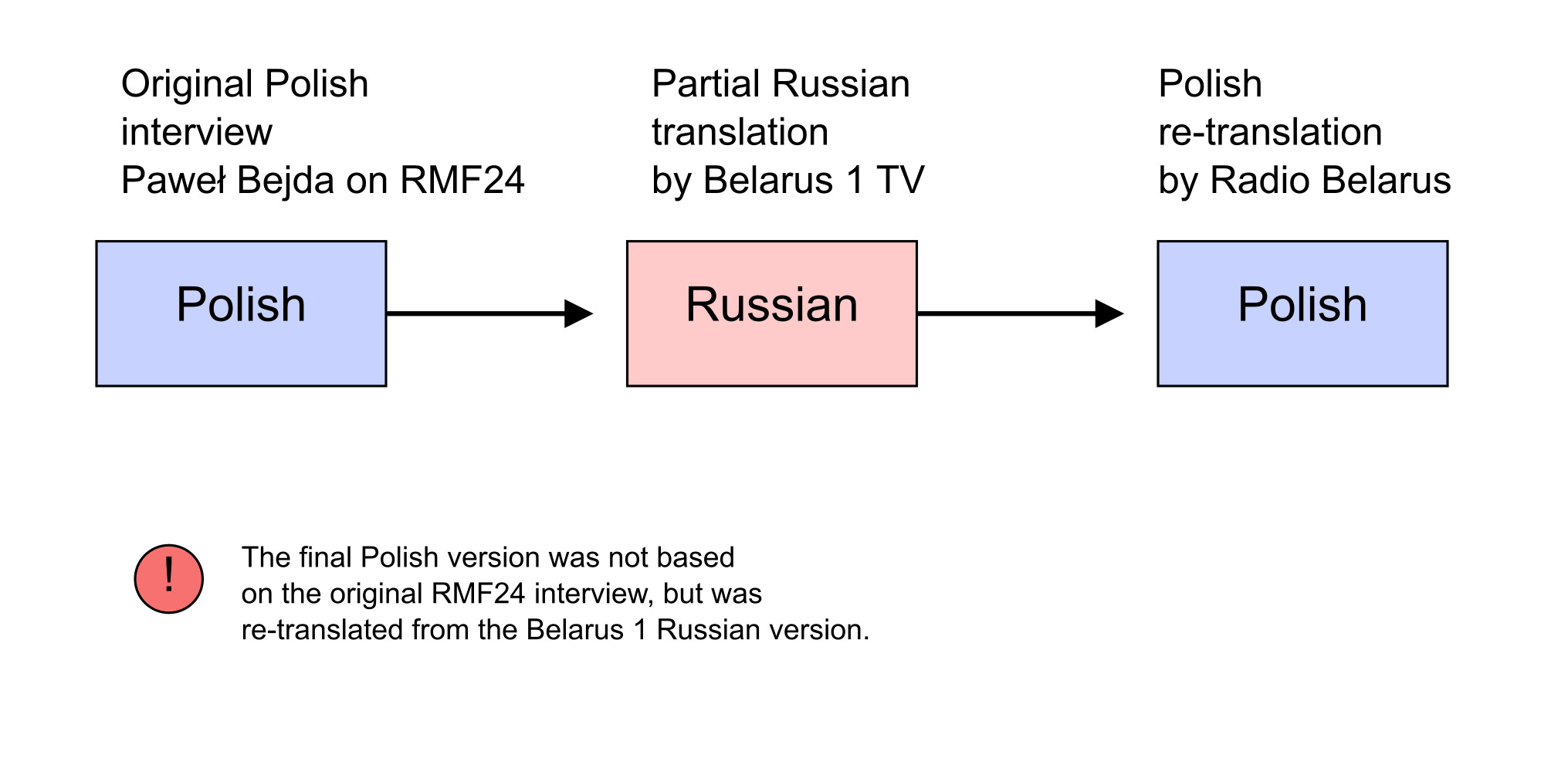

The YouTube channel of Radio Belarus featured a mix of original Polish-language content and translated materials in Russian, likely originally produced for a Belarusian audience (T0084.004: Appropriate Content). It included, among other things, broadcasts of programs from the sanctioned Belarus 1 TV station (also part of Beltelradio), widely regarded as a propaganda tool of Alexander Lukashenko’s regime. The translation tactic was used by Radio Belarus to localize content from other sanctioned entities for Polish audiences (T0101: Create Localized Content).

Some of Radio Belarus’s videos are repurposed from other channels and have gone through multiple rounds of translation. In one case, the Russian language Belarus 1 published a video that included footage taken from an interview Paweł Bejda, Secretary of State at the Polish Ministry of Defence, gave to Polish radio station RMF24. Bejda’s comments, originally made in Polish, were translated into Russian by Belarus 1. Then, Radio Belarus repurposed this Belarus 1 video and translated it into Polish for their YouTube channel. This resulted in a case where Bejda’s original Polish comments were translated into Russian by Belarus 1 and then back into Polish by Radio Belarus. This resulted in noticeable differences between the original Polish recording and the version presented by Radio Belarus.

Some of these differences were purely stylistic—lost in translation between Polish, Russian, and back to Polish. However, there are also clear signs of selective editing (T0087.002: Deceptively Edit Video (Cheap Fakes). For example, the Radio Belarus YouTube video titled, Miny zamiast pokoju? | Europa przygotowuje się do wojny-2030 | Polska marzy o broni jądrowej (“Mines instead of peace? | Europe prepares for War-2030 | Poland dreams of nuclear weapons?”) omitted a statement by Bejda criticizing Lukashenko’s dependence on Russian President Vladimir Putin, as shown in the table below. In the video Wybory bez wyboru. Co czeka Polskę w wyborach prezydenckich 18 maja? (“Elections without a choice. What awaits Poland in the presidential election on May 18?”), there are noticeable stylistic errors not present in the original Polish material, such as: “Zawsze jestem z tym pięknym polskim biało-czerwonym flagą i będę jego reprezentować,” which contains grammatical mistakes. The correct version is: “Zawsze jestem z tą piękną polską biało-czerwoną flagą i będę ją reprezentować” (“I am always with this beautiful Polish white and red flag and I will represent it”). However, both versions are misrepresentations as the original recording said, “Zawsze z tą piękną polską biało-czerwoną flagą i ją będę reprezentował” (“I am always with this beautiful Polish white and red flag and I will represent her”), which is grammatically correct and conveys the same meaning, suggesting that the quote may have gone through machine translation.

| Radio Belarus video translated into Polish | Original Polish language video from the Polish online news radio station RMF24 |

| Miny zamiast pokoju? | Europa przygotowuje się do wojny-2030 | Polska marzy o broni jądrowej – YouTube | “Błaszczak kupił gołe lufy, nie stanowią żadnej siły ognia” |

| 01:24 – Polska chce wyjść z konwencji ottawskiej. Konwencja Ottawska zakazuje używania min przeciwpiechotnych. Dlaczego chcemy wyjść z konwencji?- Nie mamy wyboru. Sytuacja na granicy jest bardzo poważna. Oczywiście mówię o granicy polsko-białoruskiej i polsko-rosyjskiej, ponieważ Polska graniczy również z obwodem kaliningradzkim, który jest rosyjskim terytorium.- Z tego, co rozumiem, chodzi o budowę pasa umocnień.- Dokładnie tak. Oczywiście, chodzi o wschodnią tarczę. To będzie jeden z elementów wschodniej tarczy. To bardzo poważne i całkiem realne zagrożenie. Chcę wam powiedzieć, że są tu takie obawy, graniczące z pewnością. Co więcej, zwróćcie uwagę, z której strony nastąpił atak na Ukrainę – z kierunku Białorusi.- Nie mamy teraz min przeciwpiechotnych?- Nie.- Jeśli ich nie mamy, to będziemy musieli je produkować. | 03:05: – Polska chce wypowiedzieć traktat ottawski. To jest traktat, który zakazuje używania min przeciwpiechotnych. Dlaczego my wypowiadamy ten traktat?- Nie mamy wyjścia, Panie redaktorze, sytuacja na granicy jest bardzo poważna. Mówię oczywiście o granicy polsko-białoruskiej i polsko-rosyjskiej, bo przecież Polska też graniczy z Królewcem – to jest ten obwód rosyjski.- Chodzi o, rozumiem, budowanie pasa umocnień i potrzebne nam są te miny piechotne?- Dokładnie tak, oczywiście. Tutaj mówimy o Tarczy Wschód – to będzie jeden z elementów Tarczy Wschód. To jest bardzo poważne i bardzo realne zagrożenie i chcę panu powiedzieć, że tutaj mamy takie obawy graniczące z pewnością, że niestety, ale Białoruś chodzi na pasku Rosji. To, co Putin powie Łukaszence, to po prostu Łukaszenka się zgodzi. Poza tym, no proszę zauważyć, z którego kierunku również została zaatakowana Ukraina – z kierunku Białorusi.- Panie Ministrze, my nie mamy w tej chwili min przeciwpiechotnych?- Nie.- Jeżeli nie mamy, to w takim razie trzeba je wyprodukować. |

| English translation | English translation |

| 01:24 – Poland wants to withdraw from the Ottawa Convention. The Ottawa Convention prohibits the use of anti-personnel mines. Why do we want to leave the convention? – We have no choice. The situation at the border is very serious. Of course, I’m referring to the Polish-Belarusian and Polish-Russian borders, as Poland also borders the Kaliningrad Oblast, which is Russian territory. – From what I understand, this is about building a line of fortifications. – Exactly. It’s about the Eastern Shield. This will be one of the elements of the Eastern Shield. It’s a very serious and quite real threat. I want to tell you that there are concerns here—bordering on certainty. And what’s more, just think where the attack on Ukraine came from—it was from the direction of Belarus. – We don’t currently have anti-personnel mines? – No. – If we don’t have them, we’ll have to produce them. | 03:05 – Poland wants to withdraw from the Ottawa Treaty. That’s the treaty that bans the use of anti-personnel mines. Why are we withdrawing from it? – We have no choice, Mr. Editor. The situation at the border is very serious. I’m of course referring to the Polish-Belarusian and Polish-Russian borders, because Poland also borders Kaliningrad—that’s the Russian exclave. – So, if I understand correctly, this is about building a line of fortifications, and we need these anti-personnel mines? – Exactly, absolutely. We’re talking here about the Eastern Shield—this will be one of its elements. It’s a very serious and very real threat. And I want to tell you that our concerns here border on certainty. Unfortunately, Belarus is acting under Russia’s command. Whatever Putin tells Lukashenko, Lukashenko simply agrees to. Also, please note the direction from which Ukraine was attacked—it was from Belarus. – Minister, do we not currently have anti-personnel mines? – No. – If we don’t, then we’ll need to produce them. But do we have that capability? |

Tomasz Szmydto frequently appeared in videos published by Radio Belarus; he is a former judge of the Voivodeship Administrative Court in Warsaw (T0091.002: Recruit Partisans). Szmydt has a segment on Radio Belarus called Conversations with Szmydt. He was involved in the “hate affair” scandal in Poland and fled to Belarus in May 2024, where he was granted political asylum. On May 10, 2024, the National Prosecutor’s Office charged him with espionage. On June 10, 2024, the Warsaw District Court issued a European arrest warrant for him in connection with the espionage investigation.

On April 6, the State Customs Committee of Belarus claimed that on April 2, they had intercepted the largest-ever shipment of explosives at the Belarus-Poland border—over 580 kg of pentaerythritol tetranitrate, a powerful explosive. However, Poland’s National Revenue Administration and the Disinformation Analysis Center at the Polish National Scientific Research Institute (NASK) cast doubt on the story, warning it may be disinformation. Amid this, Szmydt impersonated a Polish journalist, Witold Jurasz, and called several Polish institutions, including the border guards in Terespol and NASK, seeking information about the alleged smuggling. No information was revealed to him, however Belarusian media turned the calls into propaganda material.

An analysis of election topic framing in Radio Belarus broadcasts

Radio Belarus frequently releases videos designed to weaken trust in democratic institutions. A common focus is casting doubt on the fairness and transparency of Poland’s elections. Considering this, we analyzed fifty-one election-related videos posted on the Radio Belarus YouTube channel since January 15, 2025—the day the election date was announced. Each video was transcribed using the NoteGPT tool in order to track and quantify statements about the election and the three leading presidential candidates (as determined by opinion polls). The authors used targeted keywords to categorize and examine the content. The election-related topics were chosen based on an A4E, Debunk.org, and Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) country risk assessment report on Poland. The findings show that one of Radio Belarus’s key narratives was to question the legitimacy of Poland’s elections, an effort that erodes public trust.

One of the central pillars of Radio Belarus’s propaganda effort involved consistently portraying foreign influence as a threat to Polish elections and stability. In one of the videos, Szmydt claimed that Brussels would attempt to annul the presidential elections through Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who could influence the Polish Supreme Court, which, in accordance with Article 129 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland, determines the validity of the election of the president. Radio Belarus also claimed that the EU was trying to preemptively interfere in Polish elections through roundtable talks or media campaigns in order to ensure an outcome favorable to their interests.

Radio Belarus also pushed a claim that Polish elections are not truly democratic and are tainted by systemic manipulation rather than direct ballot fraud. It also claimed that establishment candidates like Rafal Trzaskowski and Karol Nawrocki served foreign interests, offering voters no real choice. The channel claimed that anti-establishment candidates were silenced by limited media access, biased coverage, and exclusion from polls. The electoral system is portrayed as designed to entrench the status quo, with the large number of candidates seen as a tactic to split dissenting votes. Instead of overt rigging, Radio Belarus emphasized “soft power” manipulation—via media, courts, and institutions—as the primary method of interference. Radio Belarus also asserted that while local vote rigging may be difficult, central manipulation of the vote count was still possible.

Another popular topic ahead of the elections in Poland is migration, which is portrayed by Radio Belarus as a burden unfairly shifted onto Poland by Western powers and EU institutions. There is a narrative that Western Europe, after accepting large numbers of migrants, seeks to offload the “excess” to Poland through EU directives and relocation schemes. These efforts are framed as attempts to protect Western societies from the costs of integration while imposing them on less influential nations like Poland. Additionally, there are claims that migrant-related unrest and social tension could destabilize Polish society and sovereignty.

Radio Belarus presented the war in Ukraine as driven by Western interests, with Poland portrayed as a subordinate actor bearing the costs. Poland’s substantial military aid to Ukraine was criticized, with claims of excessive equipment being sent to Ukraine while Poland is left vulnerable. Ukrainian forces were frequently referred to as “Banderowcy,” evoking historical resentment and implying extremism (“Banderowcy” is used as an insult toward Ukrainians, referencing Stepan Bandera’s followers who committed massacres of Poles during World War II). The narrative suggests that the West, especially the United States and France, profits from the war while using Poland as a frontline proxy state. It also implies that the war is being exploited as a pretext to justify internal militarization and undermine sovereignty by the Polish authorities.

Radio Belarus also presented LGBTQ+ issues in a highly negative light, framing them as part of a broader ideological threat to Polish society. It portrayed LGBTQ+ advocacy as being promoted by liberal politicians and foreign actors, such as Western embassies, often accusing these groups of pushing these values onto Polish youth. The narrative linked LGBTQ+ topics to alleged moral decay, comparing them to pathologies such as pedophilia, and accuses the education system of indoctrinating children with “LGBT ideology.” Overall, LGBTQ+ themes are framed not as civil rights matters, but as foreign-imposed, anti-traditional forces that undermine national values and youth.

The chart shows the frequency of mentions of key election-related topics across fifty-one Radio Belarus videos about the elections. (Sources: Flourish, NoteGPT and YouTube)

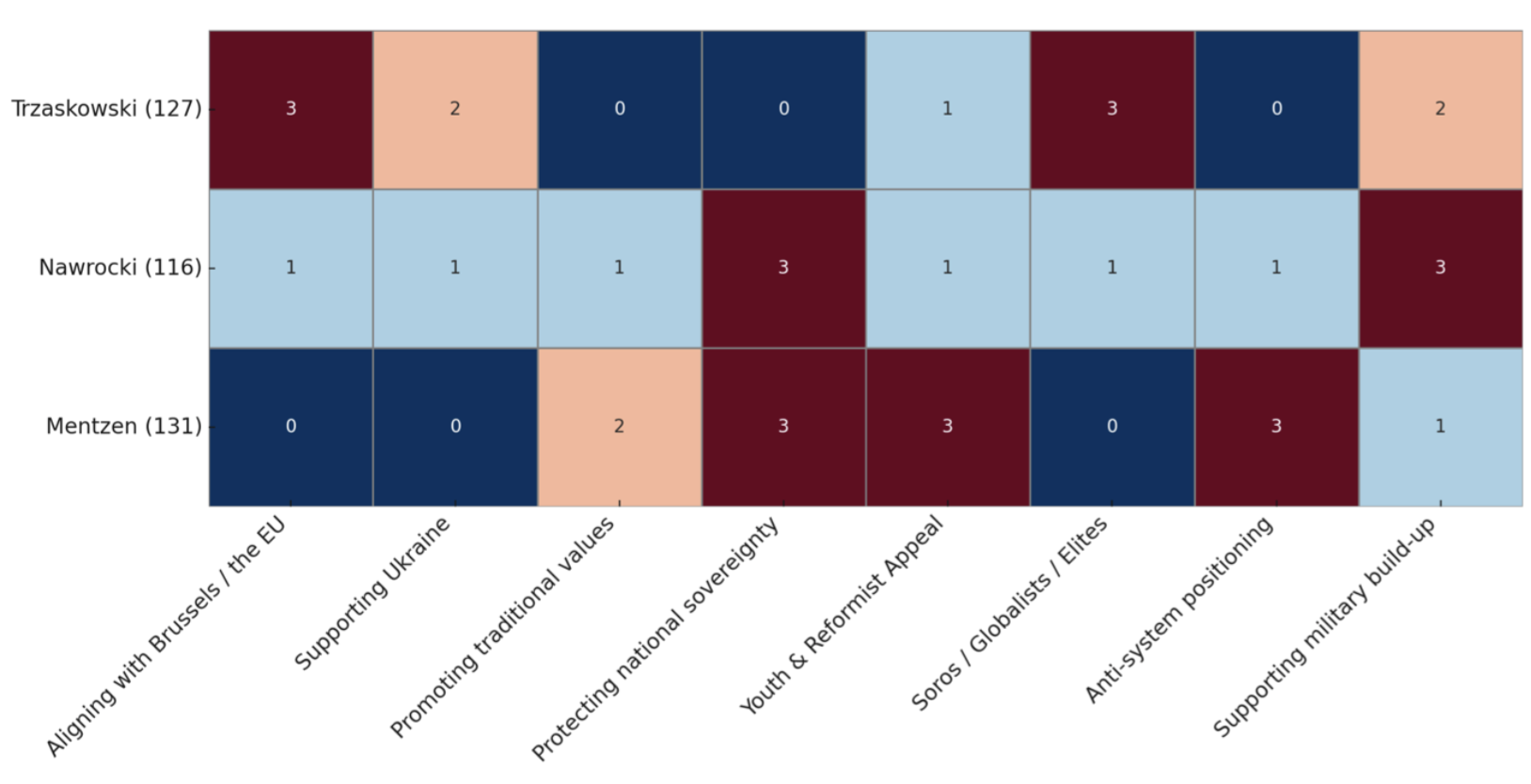

The authors also analyzed how Radio Belarus portrayed the top three presidential candidates and reviewed the narratives Radio Belarus pushed about them. The candidate from the ruling Civic Platform party, Rafał Trzaskowski, was framed as an instrument of foreign influence, representing foreign powers and undermining Polish sovereignty. The implication is that Brussels wants to secure its victory to maintain influence over Poland’s leadership. Radio Belarus speakers accused Trzaskowski of being associated with elite globalist circles, such as the Bilderberg Group and George Soros. They framed his support for Ukraine as a betrayal of Polish interests. Trzaskowski is portrayed as a carrier of cultural liberalism, often associated with the promotion of LGBTQ+ rights and undermining traditional Polish values.

Karol Nawrocki, the candidate endorsed by the main opposition party, Law and Justice (PiS), was called a “muzealny idiota” (“museum idiot”), referring to him as someone who views everything as a museum exhibit, mocking him for being out of touch with modern political dynamics. He was criticized for presenting contradictory stances — appearing anti-Ukrainian and simultaneously advocating for cutting ties with Russia. This inconsistency is portrayed as either a sign of confusion or manipulation by campaign planners. Nawrocki’s conservative stance is called hypocritical, with criticisms that he only recently started to emphasize “traditional values” to salvage declining support for his party.

Sławomir Mentzen, the candidate from the far-right coalition Confederation, is referred to as a “political wolf” with a young team capable of achievements, especially in contrast to older candidates like Nawrocki. Radio Belarus speakers emphasized that the United States, particularly the Donald Trump administration, would prefer a strong, dynamic Polish president, who would put pressure on Brussels, and Mentzen is framed as the candidate who could fulfill that role. Mentzen was presented as the most viable anti-establishment candidate when compared to other candidates. However, the speakers also suggested that the support Mentzen receives on social media could be artificial rather than genuine.

The heatmap (below) illustrates the association between the top three Polish presidential candidates and eight political topics. For each topic, a set of keywords was applied to locate relevant quotes and contextual references in the transcripts. This allowed for an analysis of how Radio Belarus speakers discussed these topics in relation to each candidate, and based on that analysis, a corresponding frequency score was determined, from zero to three.

Radio Belarus supports political candidates

While Radio Belarus discussed a range of presidential candidates and campaign developments, its coverage was highly focused on two individuals who attempted to enter the race: Maciej Maciak, who was consistently promoted by the channel, and Aldona Skirgiłło, who failed to gather the required number of signatures to appear on the ballot.

Maciak is a lesser-known figure in Polish politics. Throughout his political career, he has unsuccessfully run for various positions, including the presidency of Włocławek and seats in the Polish Sejm and Senate. On multiple occasions, he has openly declared his admiration for Putin. In Poland, to be eligible to run for president, a candidate must collect at least 100,000 signatures of support. The host of a Radio Belarus program encouraged viewers to support Maciak’s campaign by contributing endorsement signatures for his candidacy.

The Radio Belarus YouTube channel frequently covered Maciak’s campaign, including several first-hand interviews. In the videos, Maciak claimed to be the only candidate striving for peace and the only one capable of successfully negotiating with foreign states like Russia and China. He presented himself as someone who wants to protect Poland from the risk of war. In his statements, he expressed deeply anti-Ukrainian and pro-Russian views. He claimed that Ukraine is close to coming under Russian protectorate because, according to him, the Ukrainian people are “beginning to understand where good lies and where evil lies”. He portrayed Russia as Ukraine’s savior and said Russia could reveal how the West has allegedly been looting Ukraine, and that, in Maciak’s view, is what the West fears.

Maciak made claims about the lack of independence of the National Election Commission and its supporting executive body, the National Electoral Office. For example, in one interview, he claimed that employees of the National Election Office initially treated his candidacy efforts kindly when he had gathered less than 80,000 signatures. However, when they realized he was likely to exceed 100,000 signatures, their attitude allegedly changed. He suggested that this change was not coincidental, implying that external interference had influenced the commission’s conduct in order to prevent him from completing the registration process. He stated that he was instructed to correct formal errors which, he maintained, were not present. Maciak’s language can be considered derogatory and, at times, insulting. For example, in one of the videos he stated: “These are the biggest scoundrels. They’re now getting in the way of us—normal citizens, citizens who have seen through the lies—even when we’re just trying to collect signatures for a candidacy that is essential, essential to ensure that a voice of common sense is heard in this campaign.”

Another candidate who appeared on Radio Belarus was Skirgiełło, also known as Aldona z Podlasia (Aldona from Podlasie), who became involved in Polish politics in 2018. She is a member of the political party Samoobrona Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej (Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland). She has run in several elections, including local elections in 2018 and 2024, as well as parliamentary elections in 2019 and 2023, but has yet to secure a mandate.

In 2025, Skirgiełło declared her candidacy for the 2025 Polish presidential election. She was nominated as the official candidate of the Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland Party at the party’s convention in January 2025. However, her candidacy did not progress, as she failed to gather the required number of supporting signatures.

In an interview with Radio Belarus, Skirgiełło was presented positively as someone close to the people, especially the residents of Podlasie. The conversation contained clearly pro-Russian and pro-Belarusian themes, including criticism of Poland’s severing of trade relations with Russia and Belarus and the closure of the eastern border, which, according to Skirgiełło, had catastrophic consequences for the local economy and social ties. Skirgiełło spoke about the country’s decline, the looting of national assets, the lack of family-oriented policies, and the systemic neglect of regions like Podlasie. She also claimed that hostility toward Poland’s east was artificially created by the Polish media and government with the aim of weakening Slavic unity and isolating Poland from its natural neighbors.

Flagged again

On May 15, the X, YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook accounts of Radio Belarus were again flagged to the social media platforms. A subset of the authors of this report indicated to the platforms that the channels belonged to a sanctioned entity. TikTok acted and geofenced the Radio Belarus channel from EU audiences, while the other social media platforms took no noticeable action.

Conclusion

This analysis showed that Radio Belarus’s content attracted the most reach and engagement on TikTok and YouTube, while X and Facebook played more minor roles. If these dominant platforms demonstrated stricter policy enforcement, the outlet’s visibility could be sharply curtailed. The overarching objective of the Polish-language iteration of Radio Belarus is to shape public perception in Poland by combining emotional narratives and institutional distrust. Despite EU sanctions, Radio Belarus has carved out a strong digital presence by exploiting weak enforcement and leveraging open online ecosystems to disseminate state-aligned narratives.

After the publication of this investigation, X responded to the previously submitted notice, stating, “We’ve taken action on hundreds of accounts for violating our Platform and manipulation policy, specifically for content spam.”

This report was written as part of a collaboration between the DFRLab, the Political Accountability Foundation, and Alliance4Europe. Read the same report on the A4E website here.

Martyna Hoffman is a researcher with the Political Accountability Foundation, and Saman Nazari is the lead researcher with Alliance4Europe.

Cite this case study:

Givi Gigitashvili, Martyna Hoffman, Saman Nazari “Banned, yet broadcasting: How sanctioned Belarusian state media is influencing the Polish elections on social media,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) and Alliance4Europe, May 29, 2025, https://dfrlab.org/2025/05/29/banned-yet-broadcasting-how-sanctioned-belarusian-state-media-is-influencing-the-polish-elections-on-social-media/.