Kremlin-affiliated outlets find digital ally in Colombia’s oldest guerrilla group

US-designated terrorist organization ELN oversees a vast digital operation that promotes pro-Kremlin and anti-US content

Kremlin-affiliated outlets find digital ally in Colombia’s oldest guerrilla group

Share this story

BANNER: Colombian soldiers stand guard as members of a humanitarian caravan comprising senators and social organizations meet with residents to demand a ceasefire and peace in the Catatumbo region, after attacks by the ELN, in the municipality of El Tarra, Colombia, on February 4, 2025. (Source: REUTERS/Carlos Eduardo Ramirez

The National Liberation Army (ELN), a Colombian armed group that also holds influence in Venezuela, has built a digital strategy that involves branding themselves as media outlets to build credibility, overseeing a diffuse cross-platform operation, and using these wide-ranging digital assets to amplify Russian, Iranian, Venezuelan, and Cuban narratives that attack the interests of the United States, the European Union (EU), and their allies.

In the 1960s, the ELN emerged as a Colombian nationalist armed movement ideologically rooted in Marxism-Leninism, liberation theology, and the Cuban revolution. With an army estimated to have 2,500 to 6,000 members, the ELN is Colombia’s oldest and largest active guerrilla group, with its operation extending into Venezuela. The ELN has maintained a strategic online presence for over a decade to advance its propaganda and maintain operational legitimacy.

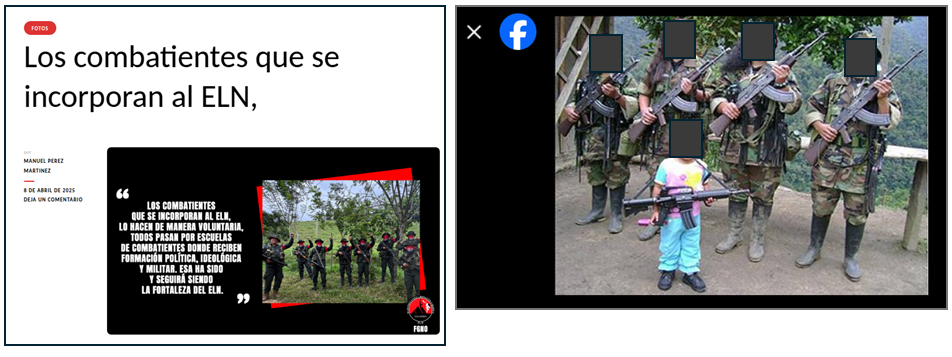

The organization, which has previously engaged in peace talks with the Colombian state, has carried out criminal activities in Colombia and Venezuela, such as killings, kidnappings, extortions, and the recruitment of minors. After successive military and financial crises in the 1990s, the armed group abandoned its historical reluctance to participate in drug trafficking. The diversification into illegal funding has meant that their armed clashes target criminal groups, in addition to their primary ideological enemy, the state forces.

In the north-eastern Catatumbo area, considered one of the enclaves of international cocaine trafficking, the group has been involved in one of the bloodiest confrontations seen in Colombia in 2025. Since January 15, the violence has left 126 people dead, at least 66,000 displaced, and has further strained the group’s engagement with the latest round of peace talks initiated by the current Colombian government. In that region, the ELN has battled with the state and other criminal groups, such as paramilitaries and other guerrilla groups, for extended control of the area bordering Venezuela, an effort to connect the ELN’s other territories of influence to Colombia, such as the north and, at the other extreme, the western regions of Choco and Antioquia.

The US Department of State reaffirmed the ELN’s designation as a terrorist organization in its March 5, 2025, update of the Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) list. This classification theoretically prevents the group from operating on major social media platforms, as US social media platforms, such as Meta, YouTube, and X, maintain policies prohibiting terrorist organizations from using their services. However, the DFRLab found that the group’s substantial digital footprint spans over one hundred entities across websites, social media, closed messaging apps, and podcast services.

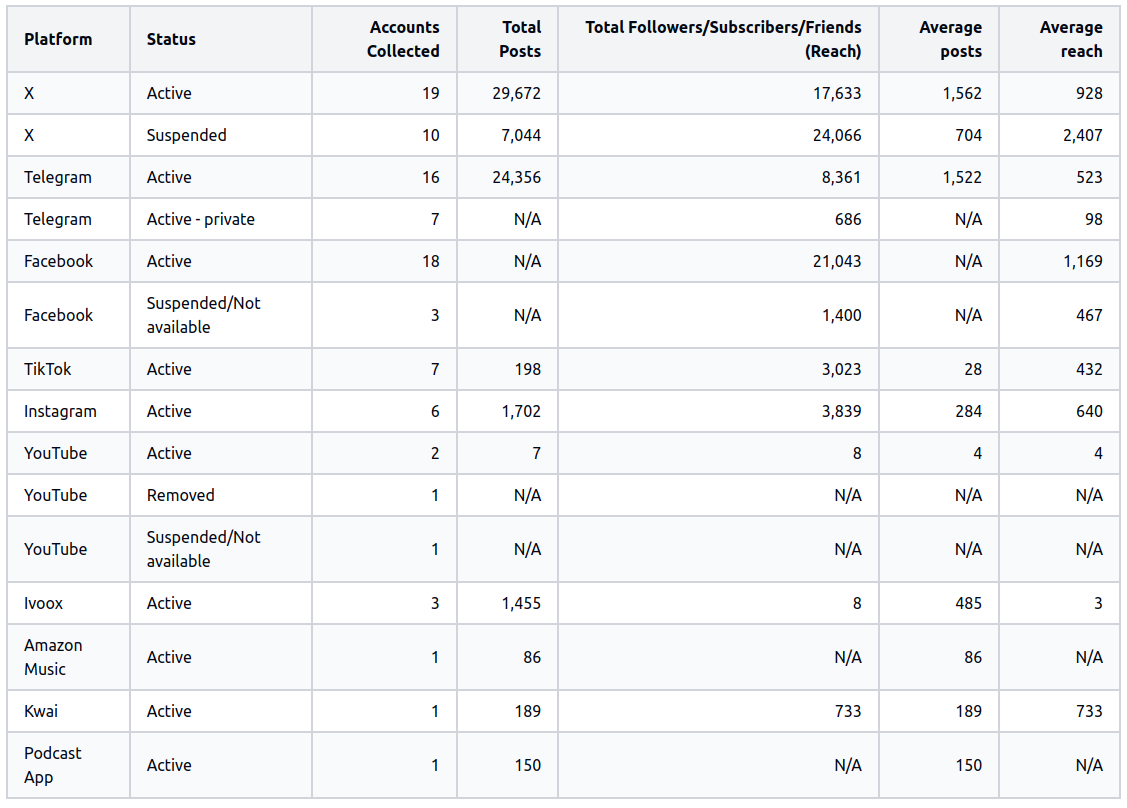

As of May 2025, amid the group’s violent offensive, the ELN maintained an active online presence. While some of the group’s accounts appear to have been suspended by social media platforms, others remain readily accessible. While the DFRLab did not identify any public reports of ELN takedowns from social media platforms, our monitoring of the ELN’s online activity indicates that, from the ninety-one accounts on social media and messaging platforms collected since April 2024, it appears that across Facebook, X, and YouTube, fifteen accounts were suspended or removed. Most of the accounts, ten, were removed or suspended from X.

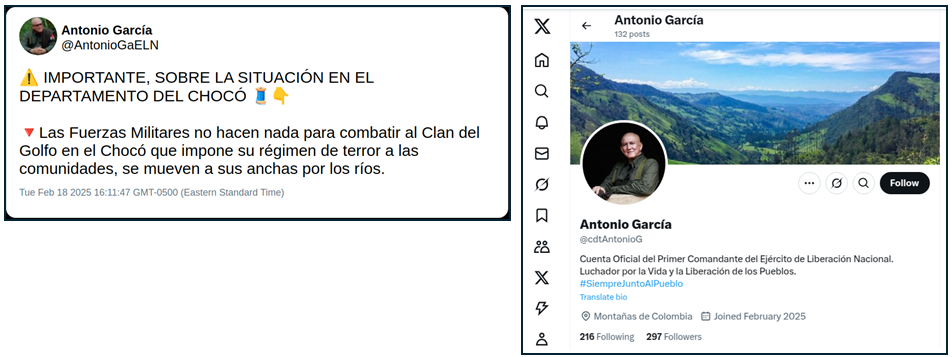

X is also the platform that has most recently acted against ELN accounts, with media outlets reporting on the suspension of at least two commander accounts after the group announced, on February 18, an “armed strike” in Choco via pamphlets and social media posts. An “armed strike” is a measure restricting the mobility of people in certain territories under the threat of detention or murder.

The suspended accounts included ELN’s leading commander, Eliécer Herlinto Chamorro Acosta, also known as Antonio García. This was not the first time X had suspended Chamorro’s accounts. In April 2023, X suspended one of his previous accounts after he threatened two journalists. The DFRLab identified that between February 19 and May 12, 2025, the ELN created seven accounts on X, including one for Chamorro.

Since 2016, the DFRLab has observed a trend in which social media platforms, primarily X (formerly known as Twitter), have suspended accounts belonging to the National Liberation Army (ELN) when its members announce “armed strikes” or perpetrate terrorist attacks during peace negotiations with the Colombian government.

From clandestine radio to digital media

The ELN has made efforts to digitize print and radio content, creating accessible repositories and targeting audiences in specific regions and cities. Their content has ranged from propaganda to promoting recruitment among minors.

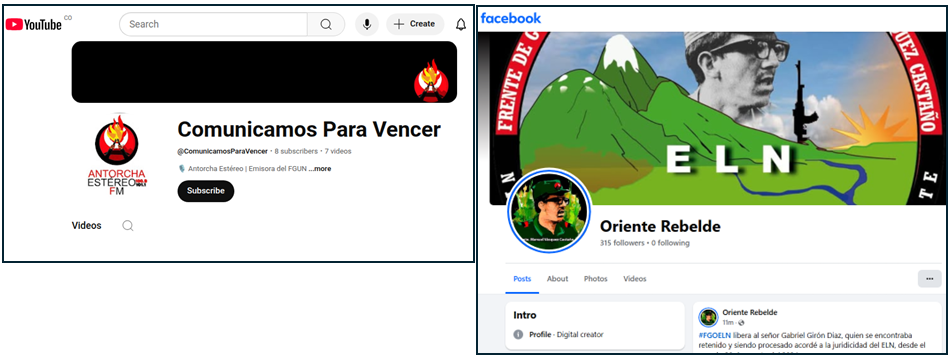

Venezuelan media outlet Armando.info published a November 2014 article outlining how the ELN used newspapers, children’s books, and the radio station Antorcha Estereo to recruit minors in Venezuela. In October 2015, the Spanish service of the BBC reported that Antorcha Estereo had been broadcasting from the Colombian city of Cucuta, and possibly from Venezuelan territory, since 2013. Antorcha Estereo was one of the clandestine radio stations operated by the ELN as part of Ranpal, the Spanish acronym for Radio Nacional Patria Libre (National Free Homeland Radio), a nationwide network of radio stations created by the ELN.

In an article signed by Ranpal members and published on November 28, 2013, on the Venezuela and Canada-based news website redpres.com, the ELN explained that Ranpal’s initial broadcast was on October 27, 1986, under the name Radio Patria Libre. The ELN also noted that on October 27, 2012, the name was changed to Radio Nacional Patria Libre as they “ventured into online radio.”

The DFRLab found archived content in the Wayback Machine of the X (formerly Twitter) account @ELN_RANPAL, self-described as the “official radio of the ELN.” The account was created in May 2013. The last archived account data, taken in February 2017, before it was suspended, shows that the page accumulated 59,618 tweets, 19,401 followers, and 3,400 likes.

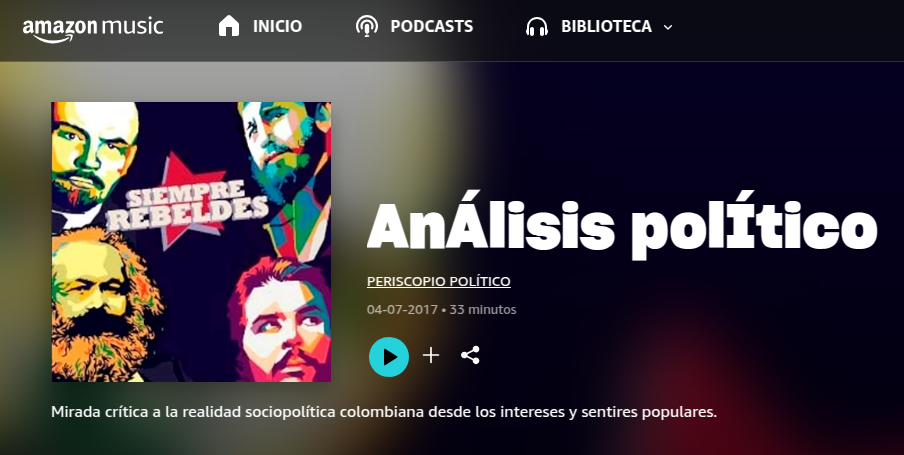

Based on evidence collected over the past year, the ELN has consistently worked to diversify the accounts and content associated with its radio stations. The DFRLab identified audio originally broadcast by Ranpal and other group-affiliated media on active accounts across podcast platforms based in the United States (Amazon Music and Podcast App) and Spain (Ivoox). The earliest content appeared on July 4, 2017, posted by the account PERISCOPIO POLÍTICO.

On April 4, 2025, the Latin American media outlet Infobae reported that the closure of radio stations by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro meant that in Venezuelan border states, such as Tachira, the only stations on the air were those of the ELN.

Although the ELN has spread propaganda and narratives related to the peace talks to portray itself as an organization that seeks peace and protects people, it has been reported by media and specialized armed conflict organizations that the group uses its social media presence to perpetrate and justify crimes against civilians, or to attack rival organizations.

The use of social networks for recruitment has been reported in various regions of Colombia, through a strategy that combines the use of platforms such as TikTok, Facebook, and WhatsApp. Other media reports evidenced the use of X and Facebook to distribute propaganda and justify armed clashes.

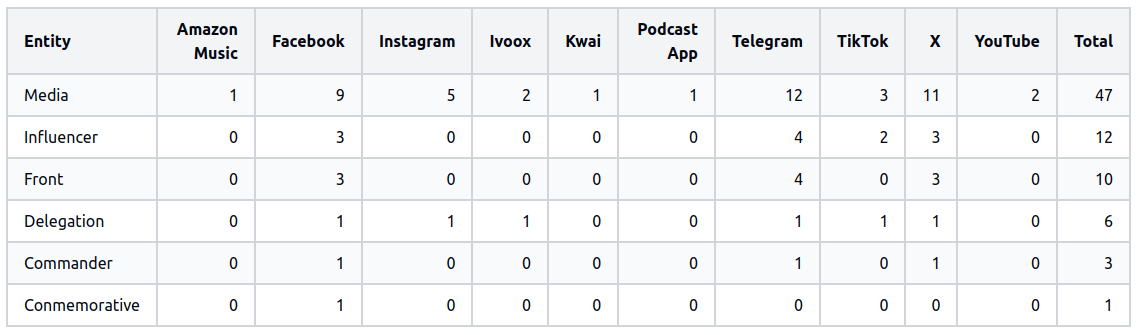

The DFRLab investigated the digital presence of the guerrilla organization across 147 digital entities, including websites (including subdomains), social media platforms, messaging services, and podcast services (Amazon Music, Facebook, Instagram, Ivoox, Kwai, Podcast App, Telegram, TikTok, X, and YouTube). For this research, the analysis focused on 111 of the active digital entities, including self-identified media outlets, members of the delegation responsible for the peace dialogues, commanders, semi-independent frontline organizations, and influencers (or self-described “digital creators”).

The analyzed content from these websites and accounts demonstrated a sophisticated, multi-platform communications strategy that amplified press releases, editorials, combat reports, propaganda videos and songs, commemorative posters, and digital versions of print and radio outputs that the group has operated for more than a decade.

According to a content analysis of ELN-affiliated media on X between April 2024 and April 2025, the DFRLab detected that ELN’s online campaigns employed a narrative framework that amplified content from Russian, Iranian, Cuban, and Venezuelan media containing ideological messages and geopolitical narratives undermining the United States, the EU, Ukraine, and NATO, an indicator that the group is seeking to generate national and international influence.

A sustained presence

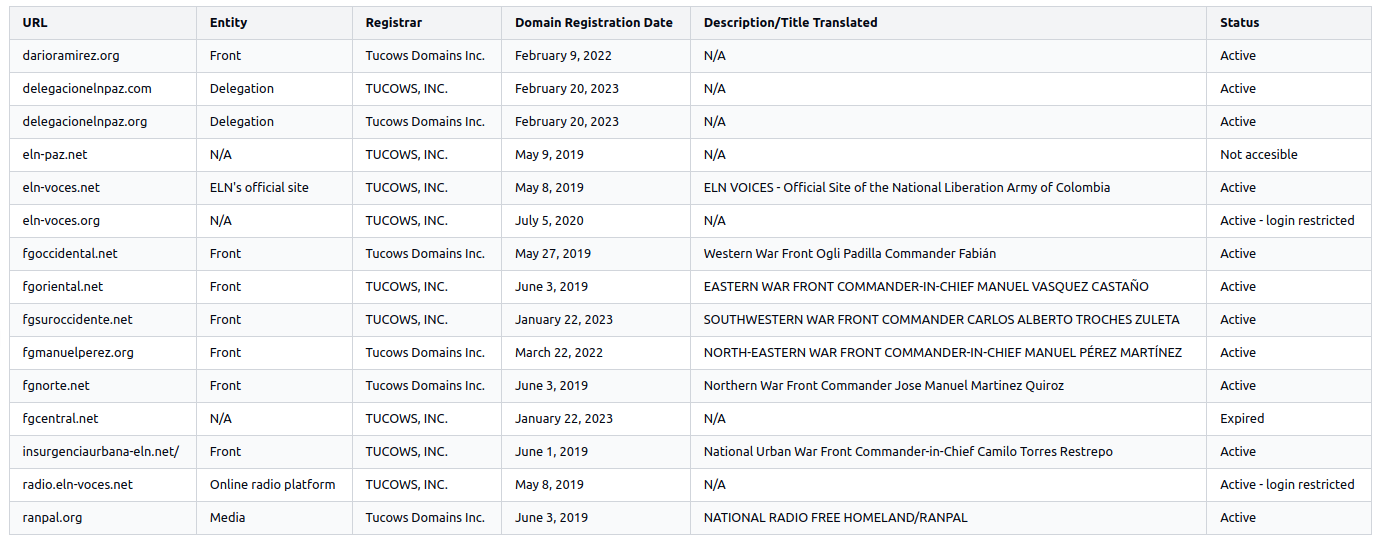

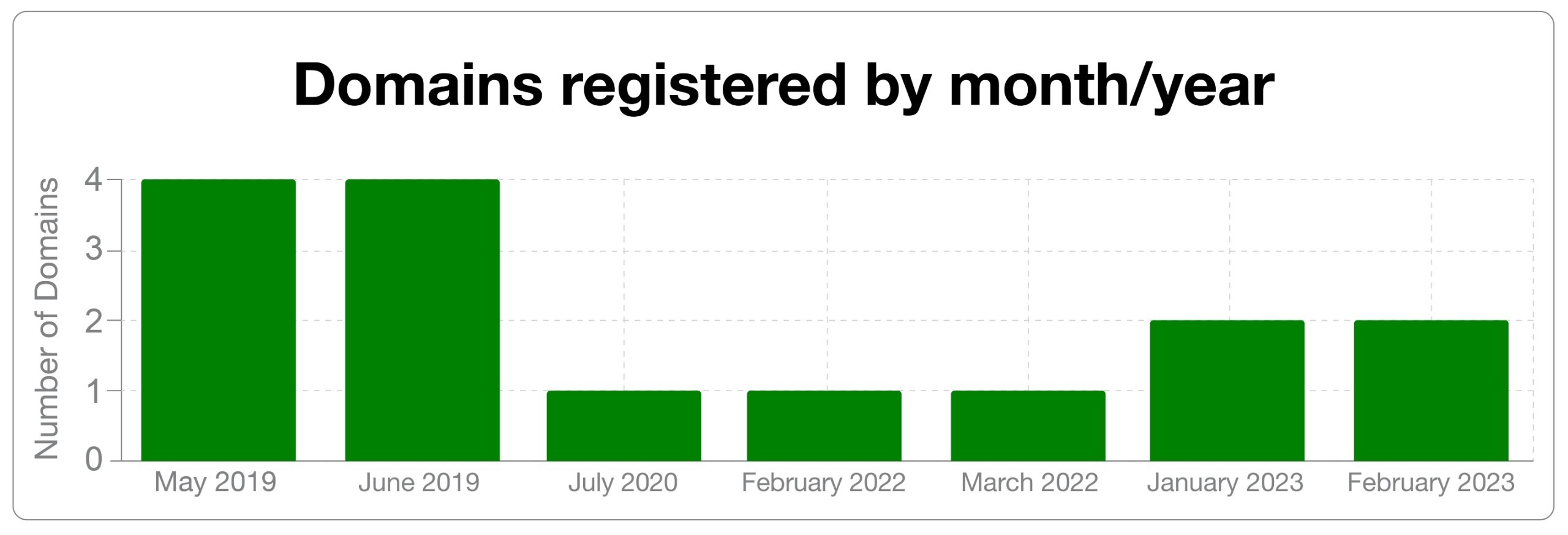

An analysis of fifteen websites revealed that the ELN maintains an extensive digital presence, comprising frontline organizations, delegations, and self-described media outlets. The DFRLab used social media posts and profile descriptions, reverse IP searches on platforms such as ViewDNS, and advanced Google searches to identify the URLs. The searches identified twenty-one suspicious domains, six of which were not accessible. The analysis for this piece included one subdomain, radio.eln-voces[.]net, which serves as a digital broadcaster for ELN’s radio station. The website eln-voces[.]net is the group’s official platform, containing content that is replicated on other websites and digital platforms. Most of the content is in the form of press releases, op-eds, interviews, operational information, messages to security forces, and communications related to peace dialogues.

The ELN operates a confederated structure, in which political decisions are made by the Central Command (Comando Central, or COCE in Spanish). Throughout the different regions of Colombia and Venezuela where the ELN operates, there are at least eight self-denominated frontline organizations (“frentes de guerra” or war fronts) that maintain operational and financial autonomy. Their digital presence reflects this structure—websites associated with these frontline organizations publish reports on armed clashes, communications from Chamorro or front commanders, and some distribute music videos or digital versions of magazines and radio programs tailored specifically to audiences within their territorial areas of influence.

The ELN’s communications infrastructure relies heavily on website domains, allowing the organization to distribute content across multiple URLs while maintaining resilience against potential shutdowns. The group has developed a sophisticated backup strategy, with multiple domains replicating the same content (for example, delegacionelnpaz[.]org and delegacionelnpaz[.]com), enabling them to adapt to suspensions or restrictions, and maintain consistent messaging to their target audiences.

Among all the examined digital entities, websites had the longest uninterrupted online activity. Among the examined domains, the earliest one was in operation as of 2019. The website fgcentral[.]net was the only one whose domain registration had expired. Additionally, the DFRLab found archived versions of the website eln-voces[.]org in the Wayback Machine, revealing that it had maintained an online presence since 2010.

Narratives

A review of nineteen articles from eleven websites that actively published content revealed that the ELN consistently amplified narrative themes promoting anti-US and anti-imperialist messages, claiming that the “US-plutocracy” opposed Colombia’s democratization. The DFRLab selected for examination the most recent articles published on each website that mentioned the ELN’s stance regarding the United States, geopolitics, or media.

The group presents contradictory positions by simultaneously displaying criticism and support for Colombian President Gustavo Petro’s policies. For example, one article claimed that the Colombian government is subordinate to US interests, while another publication endorsed the announcement of a referendum to approve Petro’s stalled health and labor reforms, which they favorably describe as a participatory exercise to confront a “reactionary power” backed by the “gringa [pejorative term for US citizens] oligarchy.”

The ELN also promotes negative narratives targeting NATO and its members. One article described the EU as “a new lord of war.” Regarding the Ukraine conflict, the organization portrayed Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as a “little dictator” supported by “Biden’s government, the European Union, and the United Kingdom,” while claiming Ukraine had attacked Russia since 2014. This geopolitical framing aligns the group with similar narratives that the Kremlin has promoted in Latin America.

The Kremlin sees Latin America as a means of indirectly influencing and intentionally diminishing the relative power of the United States and the European Union. In the context of the war in Ukraine, Russia tailors its anti-Ukraine messaging and its diplomatic focus to topics resonating in the region, such as sanctions and claims of US imperialism, while promoting the rise of a multipolar world. Russian state media outlets, such as RT en Español and Sputnik, have a significant audience in Latin America, creating fertile ground for disseminating pro-Kremlin narratives.

‘Alternative media’ strategy

The strategy used by the ELN websites appears to be similar to the group’s strategy for content amplification via social media platforms, closed messaging apps, and podcasts. Beyond the websites identifying themselves as frontline organizations, delegations, or media, the DFRLab identified social media accounts that could be categorized in other ways, based on their content type and self-designation, these categories include: commemorative, commanders, or influencers/digital creators.

It is worth noting that the ELN’s recent digital media presence reflects a strategic effort to reach specific audiences beyond their territorial influence with content that conceals their militaristic and violent nature. The group leverages self-described media outlets that potentially serve as gateways for digital audiences who may either support their peace initiatives or be drawn into recruitment.

The examined accounts often fell into two categories simultaneously. For instance, some accounts used profile pictures of front logos while self-identifying as “informative units” or including links to ranpal[.]org in their account descriptions.

The DFRLab detected that accounts on Facebook, X, and YouTube appear to have been affected by platform suspensions. However, the ELN regenerates by creating accounts with identical usernames that often amass hundreds of followers within days or weeks. As shown in the table below, the ten suspended X accounts garnered an average of 2,407 followers per account. The newly created and still active X accounts analyzed by the DFRLab garnered an average of 928 followers as of May 12.

The ELN’s recent digital strategy involves diversifying content and ensuring audiences have access to various forms of content with identical messaging, as evidenced by the emergence of multiple accounts associated with ELN media outlets on social media, podcasts, and closed messaging platforms. This strategy emphasizes diffusion and can be useful when faced with suspensions. Establishing these various accounts and podcasts enables the ELN to expand its reach to audiences beyond the scope of its print and digital publications, or its radio frequencies. Moreover, the accounts that portray themselves as media outlets create the impression of an established and credible entity, which fosters audience trust that the organization cannot attain through profiles that explicitly identify as fronts of an armed group characterized by the use of violence in offline environments.

Campaigns to promote the ELN’s media outlets appear consistently across numerous website articles. The ELN makes a distinction between what they consider traditional, or hegemonic, media and their self-described “alternative media.” In an article posted by ELN’s North War Front, the group criticized mainstream Colombian outlets such as Semana, El Espectador, and La W, as instruments of disinformation and war. In contrast, the ELN defines its own media outlets as communication channels that seek peace and protect sovereignty amid a “communicational battle.”

As described in an article authored by ELN top commander Chamorro, the group’s media strategy aims to challenge Colombian government discourse and opposes alleged “media manipulation” implemented by the United States in Latin America. Chamorro also claims that US narratives about “repressive dictators” in “popular democracies” are manipulative scripts designed to justify interventions. In the ELN’s North War Front article mentioned above, the ELN similarly claimed that Colombian media outlets were “chained” to global media conglomerates that followed a strategy implemented by the United States, in which Washington is portrayed as making decisions on wars, invasions, and genocides in Colombia, Syria, Ecuador, and Haiti.

The ELN’s digital strategy boasts of its “alternative media” branding as a political and ideological achievement. For instance, in describing the objectives of one of its digital media entities, the ELN’s North War Front outlet El Karibeño Rebelde, the ELN explained that its media outlets operate within the “insurgency” and protect the “essence of the armed fight.”

Anti-US amplification via media outlets

The DFRLab identified connections between the ELN and state-affiliated media outlets that disseminate anti-US and anti-EU narratives throughout Latin America, particularly those with ties to Russia and Iran. Using the social media listening tool Meltwater Explore, the DFRLab gathered 5,545 posts from eighteen X accounts linked to ELN media, frontline organizations, commanders, and influencers. The analysis covered the period from April 24, 2024, to April 24, 2025.

Among the examined ELN accounts (@fgno_camilo, @informat_e, and @karibe_rebelde) that frequently engaged with Kremlin-affiliated media accounts (@ActualidadRT, @ahilesvainfo, @ahilesvavideos, and @SputnikMundo), the account @karibe_rebelde most frequently promoted Russian accounts, with 144 posts.

A manual review of the mentions by @karibe_rebelde showed that it amplified topics primarily centered on international policy matters concerning US influence in Latin America, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the Israel-Palestine conflict. The terms “Russia” and “EE.UU.” (the Spanish acronym for United States) ranked among the most frequently used words, appearing twenty-eight and twenty-three times, respectively. Notably, Colombia-related terms such as “Colombian” or “Petro” were absent from the posts.

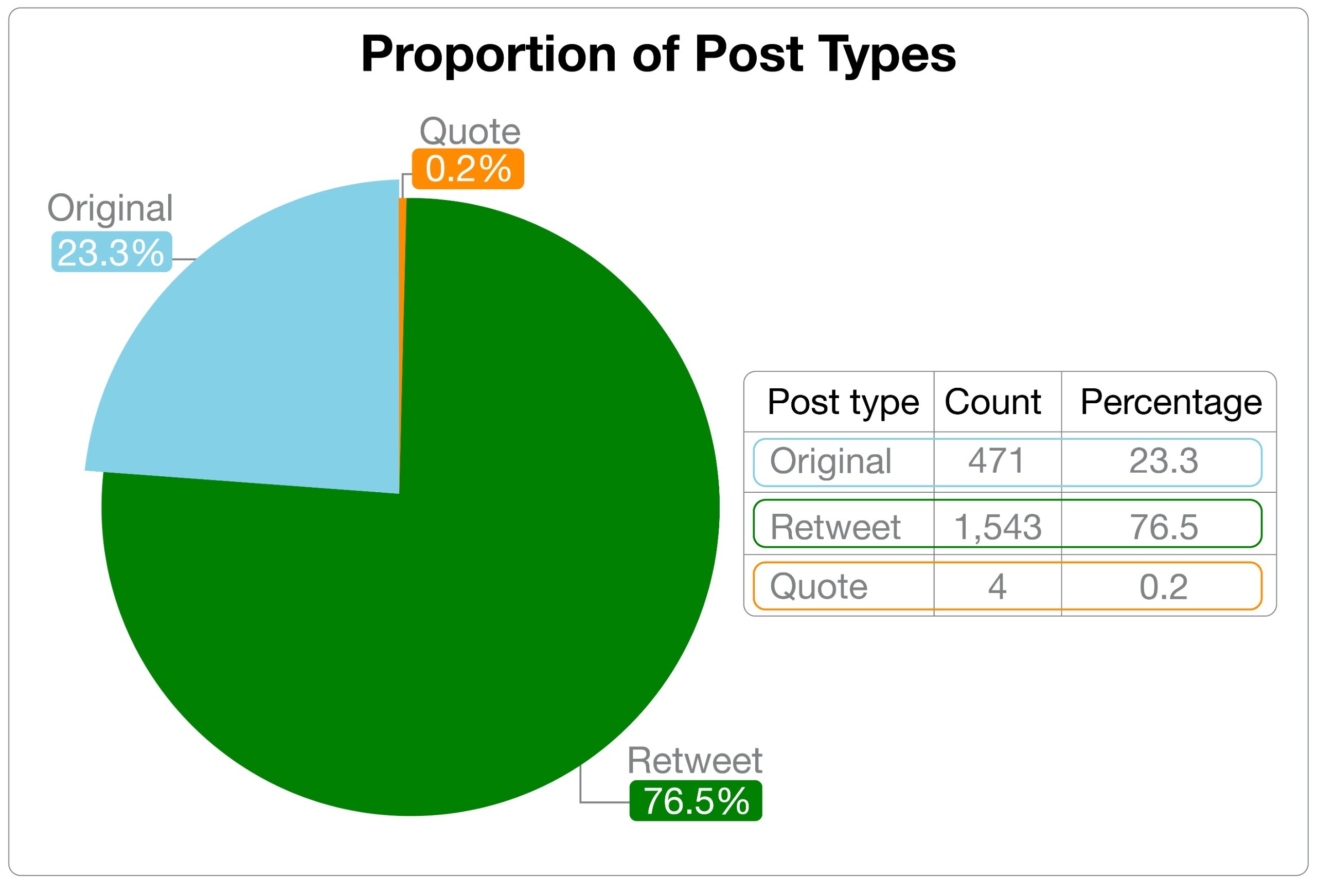

An examination of post types by @karibe_rebelde from April 24, 2024, to April 24, 2025 revealed that retweets and quotes constituted 76.7 percent (1,547) of its 2,018 total posts.

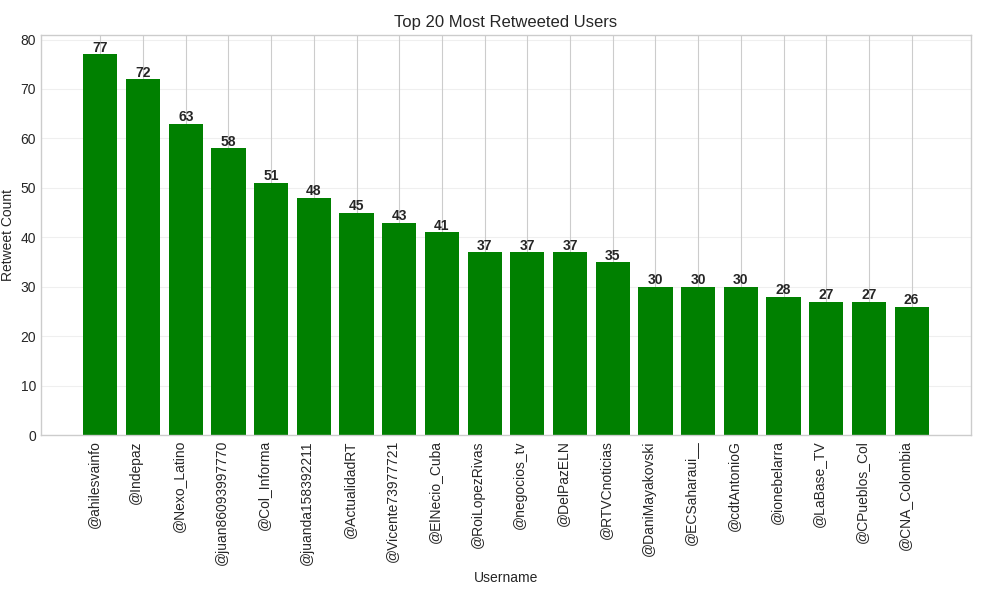

The analysis of these 1,547 mentions indicated that @ahilesvainfo, a Spanish-speaking program affiliated with the Kremlin state media outlet RT, received the most amplification with seventy-seven retweets. As shown in the table below, the twenty most retweeted accounts also included @Nexo_Latino, from the Iranian Spanish media outlet Hispan TV; @ActualidadRT, the Spanish branch of RT; and @LaBase_TV, part of a digital media conglomerate established by former vice president of the Spanish central government Pablo Iglesias, which has hired and platformed former RT journalists to disseminate Russia-aligned narratives throughout Spanish-speaking regions of Europe and the Americas.

The above findings, regarding mentions of the four Kremlin-affiliated accounts, demonstrate that El Karibeño Rebelde dedicated significant effort on X to position the ELN within international geopolitical discourse, focusing primarily on the United States and its allies’ role while distancing itself from Colombian geopolitical matters, despite having operated in this territory for over six decades.

Conclusion

The ELN’s campaigns across digital platforms demonstrate how terrorist organizations can evade moderation standards while amplifying geopolitical narratives from state actors. The ELN’s digital strategy legitimizes its violent actions while amplifying foreign state narratives. This creates concerning information vulnerabilities that require more rigorous platform enforcement and international cooperation to prevent armed or terrorist-designated groups from exploiting online services.

Cite this case study:

DFRLab, “Kremlin-affiliated outlets find digital ally in Colombia’s oldest guerrilla group,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), June 16, 2025, https://dfrlab.org