Cross-platform campaign accuses Moldova’s Sandu of meddling in Romanian elections

A network of more than 200 coordinated accounts targeted Romania in a months-long operation supporting Simion and Georgescu

Cross-platform campaign accuses Moldova’s Sandu of meddling in Romanian elections

Share this story

BANNER: A woman exits the Central Electoral Bureau, ahead of the second round of the presidential election, in Bucharest, Romania, on May 17, 2025. (Source: REUTERS/Louisa Gouliamaki)

A coordinated network of at least 215 multi-platform accounts is spreading unfounded accusations against Moldovan President Maia Sandu, claiming she interfered in Romania’s elections. The pro-Russia network, active since December 2024, initially expressed support for former Romanian presidential candidate Călin Georgescu, and then pivoted to support far-right candidate George Simion, who lost Romania’s May presidential election to Nicușor Dan.

Romania held a second presidential election in May, following the unprecedented annulment of the country’s 2024 presidential election, which the Constitutional Court invalidated citing credible allegations of Russian interference that benefited far-right candidate Georgescu. Georgescu was barred from running in 2025 and faces a criminal investigation, giving way for Simion. On May 18, the day of the second round of voting, Telegram CEO Pavel Durov alleged that France sought his assistance in banning “conservative voices in Romania ahead of elections.” France’s Directorate General for External Security (DSGE) said it “strongly refutes” the allegations.

The network, composed of inauthentic and seemingly hijacked Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok accounts, spread anti-European Union (EU), pro-Russian, and anti-Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) narratives. It amplified pro-Russian and pro-Georgescu claims in the aftermath of the annulment of the December 2024 presidential elections. It then switched to publishing content that was supportive of Simion, criticized the EU, amplified Durov’s claims of election interference, and made accusations of election meddling against Sandu.

The network’s posting activity surged in February, April, and May, with multiple coordinated posts spread across various hashtags in Russian and Romanian. At the time of writing, the DFRLab identified, by accessing publicly available social media data, 116 accounts on Facebook, seventy-nine on TikTok, and seventeen on Instagram, publishing a total of 8,514 posts spanning from December 2024 to June 6 that used coordinated hashtags and posts. Altogether, the network amassed at least 16 million views and 681,000 likes across the three platforms.

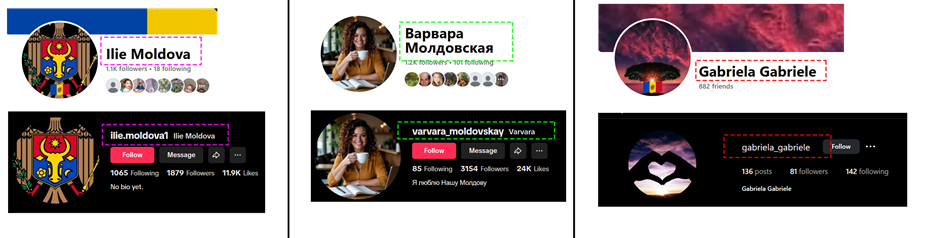

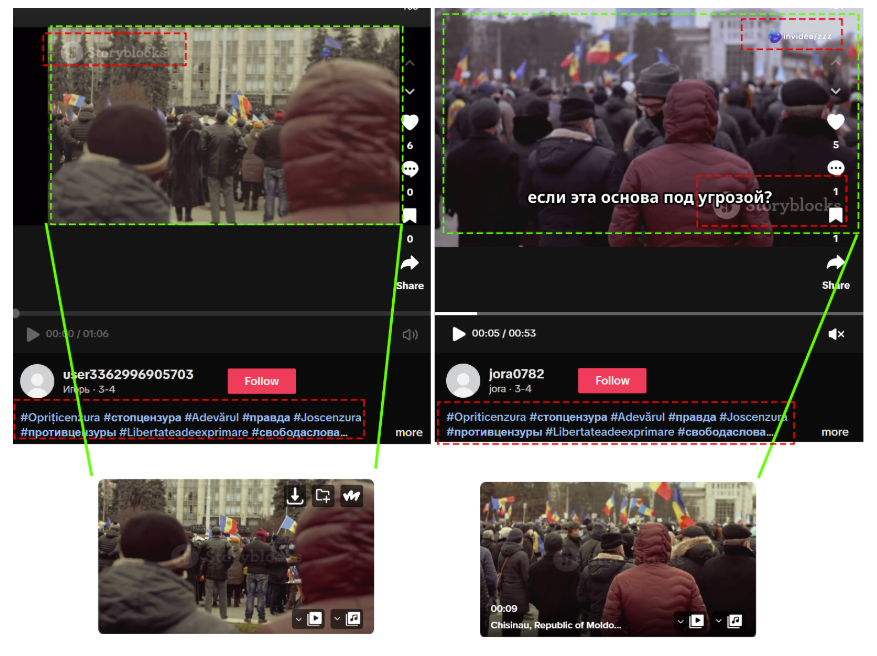

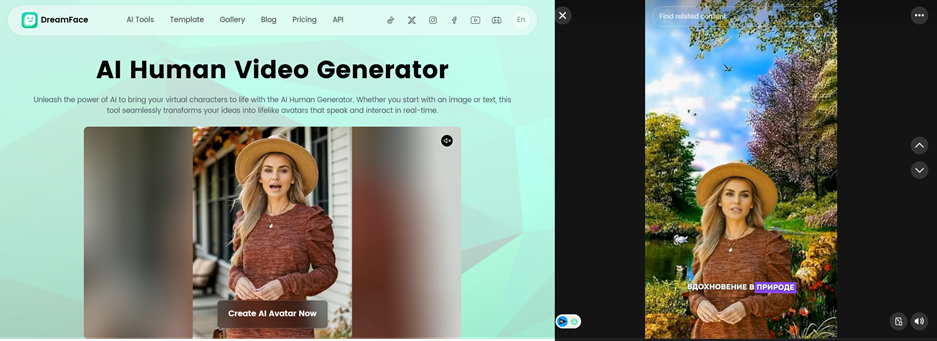

The network published slideshows, photos, and videos on TikTok and Instagram, and images and text posts on Facebook. The various posts were coordinated across the three platforms using hashtags. Generative artificial intelligence was employed in posts and profile pictures. The network created fake personas with Romanian-sounding names across multiple social media platforms. Multiple accounts on Facebook appeared as “professional accounts” or “digital creators” and shared content with news-related Moldovan Facebook groups. The network also utilized online AI video clip editing solutions and AI avatars, reinforcing the idea that the network relied on AI for automated content generation and dissemination.

Smaller followings

When using the Meta Content Library and API to investigate the network, the DFRLab found that Meta reported on only fifty-five of the accounts, as the other sixty-six accounts did not meet the threshold for inclusion in the public dataset—Meta’s Content Library and API limit data access to pages and accounts with more than 1,000 followers. It is plausible that this is a strategy that could be employed by actors to avoid detection by Meta platforms. Given the likelihood that some accounts may remain undetected, the estimated posting activity, reach, and engagement generated by the network could be more significant than the findings suggest. To complement the findings, additional data was gathered using tools that accessed publicly available social media posts.

Additionally, at least twelve accounts self-identified as “professional accounts” presenting themselves as “digital creators,” a feature dedicated to content creators that enables the authors of such profiles to publish monetized content. There is currently no public mechanism to determine whether the operation received any earnings via this program.

The ‘Moldovan scenario’

Throughout May, the network escalated its campaign, sharing multiple narratives that accused Moldova and the EU of election interference. Between May 9 and May 28, 1,452 videos were published, about 16.7 percent of the total number of videos posted since the network’s inception, as of the time of writing. The videos shared narratives accusing Moldovan citizens with Romanian passports of interfering in Romania’s presidential election process.

Most of present-day Moldova (historical Bessarabia) was part of the Kingdom of Romania from 1918 to 1940. In 1940, the Soviet Union formed the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic from most of Bessarabia plus a strip east of the Dniester. Romania reoccupied the territory in 1941–44, then it was returned to the Soviet Union in 1944 (confirmed by the 1947 treaty). Moldova gained independence in 1990, and Romania joined the EU in 2007. Nevertheless, nearly one in four Moldovan citizens also holds a Romanian passport, including Moldova’s President Sandu. Romanian law allows individuals with Romanian ancestry, including those from the Bessarabia region, to obtain Romanian citizenship.

On May 19, the network’s activity surged again with 106 videos posted, seventy-seven of which used the same set of hashtags, posted in both Romanian and Russian:

- “#TheGlobalistsAreLosing” (#глобалистыпроигрывают and #globalistiipierd)

- “#PowerIsChanging” (#властьменяется and #putereaseSchimbă)

- “#EUDivision” (#расколЕС and #divizareUE)

- “#PoliticalPressure” (#политическоедавление and #presiunepolitică)

- “#MoldovanScenario” (#молдавскийсценарий and #scenariumoldovenesc)

Among these videos, twenty-one specifically mentioned pro-European candidate Dan, following Sandu’s public endorsement of him. The videos claimed that “the regime of PAS/Sandu [dragged] dozens of thousands of Moldovans with Romanian passports into a foreign political struggle.”

Videos accused Sandu of interfering in Romania’s electoral process after the May 18 second-round vote. For instance, one TikTok video description reads, “The Moldovan scenario is repeating itself, the people are voting for one person, and another one wins. The puppet Maia Sandu played her role, 158,000 Moldovans with Romanian passports voted when needed.”

Throughout May, the network posted fifty-six videos concerning Simion, anti-EU narratives, accusations of interference against France and Moldova, and amplification of the interference claims originating from Telegram CEO Durov. In at least thirty-five posts in the lead-up to, during, and after the second round of the Romanian presidential elections, the network amplified a narrative that claimed Simion referred to Sandu as an “obedient girl” (“послушная девушка” in Russian), obeying the “globalists” and the “EU.”

A line chart showing a threefold increase in TikTok viewership on May 22, following the second round of the Romanian presidential election on TikTok.

An anti-PAS and anti-Sandu operation

The network primarily focused its activity on publishing anti-PAS and anti-Sandu posts that criticized the Moldovan government and Sandu’s political party. A total of 2,298 videos alluded to Moldova’s PAS party, either by accusing the leadership of scandals or by including hashtags targeting PAS directly, mainly in Russian, such as “#PASThiefs” (#PASВоры), “#PASCorruption” (#PASКоррупция), “#PASLiars” (#PASОбманщики).

The network also amplified pro-Russian and anti-Romania claims, calling for a more “independent Moldova.” Seventy-nine posts published between February 22 and May 27, contained the hashtag “#UkrainianScenario” (#Украинскийсценарий and #scenariuucrainean), accusing Sandu and the ruling party of “dragging Moldova into a foreign war.” Other hashtags included “#TheyAreDraggingMoldovaToWar,” (in Russian #Молдовувтягиваютввойну and #Moldovaîmpotrivarăzboiului) “#MoldovaAgainstWar,” (#Молдовапротиввойны in Russian and #Moldovaestetârâtăînrăzboi in Romanian), and “#WhyArmingUp,” (#зачемвооружаться in Russian and #Pentrucesăînarmezi in Romanian) questioning the country’s defense policy as the war in Ukraine wages on.

In one instance, amid the backdrop of April attempts by the United States and Russia to engage in discussions about the war in Ukraine, one video’s description read, “While Trump and Putin are discussing peace, Sandu and PAS continue to be in awe of [Ukrainian President Volodymyr] Zelenskyy. But he’s the one who cut the gas transit, and Moldova was out of heat and light. Why are the interests of Moldova the victims of others’ games? We’re dragged into a foreign war, a foreign policy, and foreign ambitions.”

The network’s posting activity surged on May 8, with 115 posts across Instagram and TikTok celebrating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, using the Russian hashtag #VictoryDay (“#ДеньПобеды”). The network also posted videos with the hashtag “#NoToEuropeDay” (#НетДеньЕвропы), referencing a celebration instituted in the country in 2006, which has come under criticism since the adoption of the referendum on Moldova’s EU membership in October 2024.

Between February 25 and April 1, 128 posts used the hashtag “#NoToRomania,” (#НетРумынии) seeking to create a divide between Romanians and Moldovans by publishing claims criticizing the adoption of the Romanian language into Moldova’s constitution. Ninety-four posts used the hashtag “#FreeMoldova” (#СвободнаяМолдова), with multiple calling Sandu an “illegitimate president” and arguing that Moldova’s European integration would also lead to reunification with Romania. Multiple posts also called for Sandu’s resignation.

In early June 2025, the network started publishing posts and videos in support of the Russian language. Although a small percentage of the Moldovan population are native Russian speakers, many Moldovans comfortably use Russian as a second language.

Network amplifies support for arrested candidates and officials

Between March and May 2025, as Romania’s presidential election unfolded, the network escalated its pro-Georgescu stance and championed Gagauzian Governor Evghenia Guțul, both of whom faced arrests.

The network’s posting activity surged significantly between March 4 and 5 as protesters in Bucharest rallied in support of Georgescu following his February 25 arrest. On March 5, the network used the hashtags “#StopCensorship” (“#стопцензура” in Russian and “#Oprițicenzura” in Romanian) in seventy-eight TikTok videos and thirteen Instagram posts. Between March 10 and March 12, the posting activity surged again, as the Constitutional Court barred Georgescu from running in the May 2025 presidential election.

In addition, the network published 150 videos between February 2025 and June 2025 using the hashtags “#NoToRomania” (#НетРумынии and #NuRomânia) or “#NoToTheEU” (#НетЕС and #NuEU), amplifying anti-EU narratives before and after the February 25 arrest of Georgescu. Altogether, the network published forty-eight videos that alluded to Georgescu in the description, thirty-six of which emerged between March 1 and March 5.

A line chart showing surges in posting activity on TikTok and Instagram. (Source: DFRLab via Flourish)

The network also reposted multiple videos of the Soviet-era Red Army song “Katyusha” using the song’s name as a hashtag, intended as a sign of support for Gagauzian Governor Guțul, who was placed under pre-detention arrest by the Buciuani court in Moldova on March 27. The hashtag was used in eighty-seven posts on Instagram and TikTok. In one post, the network reposted declarations from Shor, who claimed that “there [was] no legal basis for the arrest of Evghenia Guțul.”

A March 3 video, posted after the pre-detention arrest of Guțul gathered nearly 300,000 views on TikTok.

Stolen accounts and fake personas

Multiple accounts in the dataset were active before Fall 2024, posting family pictures and seemingly genuine content. The accounts then began disseminating inauthentic content, signaling that the accounts may have been hijacked, stolen, or repurposed, a method of accessing an existing audience and exploiting pre-established trust. Across 215 recovered accounts, multiple used the same fake identities across Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok accounts. Timestamp analysis also shows coordinated posting across the entire network.

Multiple accounts also appear to have infiltrated two local news groups on Facebook. The group “News Portal of the Gagauz Autonomy” and the Romanian and Russian-language group “News in Moldova” appear to have been targeted by multiple accounts in the network. The two groups are public and welcome more than 13,300 and 17,100 members.

The network widely used stock footage and generative AI to create fraudulent accounts and videos, often utilizing AI-generated profile pictures, video descriptions, and avatars. Some of these AI-generated elements were shared across multiple videos.

The network’s operators also utilized Storyblocks, a platform that provides stock footage to content creators, which was used to illustrate protests following Georgescu’s arrest. In actuality, the footage provided by Storyblocks dates back to December 2020.

Similarly, the network used the program DreamFace, an “AI human generator” that creates fake personas to present video content.

Ono.news

In addition, the network operators appear to have employed an inauthentic news/marketing channel, ono.news, to disseminate video content. The accounts remained active on Telegram and TikTok at the time of writing, but appear to have been deplatformed by Facebook. The earliest posts by the news account on Facebook date back to May and were linked to a Facebook account purporting to be an individual named Gabriel Matei. Matei’s profile picture bore a strong resemblance to a person depicted in the early ono.news TikTok uploads. This suggests that the account was originally established as an inauthentic persona before pivoting to take on the brand identity of a fraudulent news channel.

The ono.news TikTok and Telegram accounts featured an AI-generated profile picture, and videos on the TikTok account include the watermark of D-ID, an AI company specializing in the creation of “visual AI agents.”

Conclusion

Romania’s presidential elections, both in late 2024 and the spring of 2025, were associated with claims of foreign interference, both online and via actions from the respective candidates. The cross-platform operation outlined above demonstrates that the electoral integrity of a country remains fragile in the online space and is prone to covert cross-platform online influence campaigns. The operation targeting Romania does not appear to fall under domestic laws on political advertising. Its covert nature makes it hard for domestic and international monitoring bodies to establish who is behind the campaign.

This operation shows versatility in the narratives employed. They gradually expanded from narratives specifically targeting Sandu and Moldova’s ruling party to incorporate accusations of interference during Romania’s presidential election. Altogether, the evidence gathered shows that a complex and industrialized disinformation community, active in Moldova, has deployed known methods to impersonate and mislead online audiences. That involved accusing heads of state of election interference in other countries within the EU and spreading anti-EU messaging.

It is difficult to estimate the efficacy of the operation, despite the associated accounts garnering a collective 16 million views and 681,000 likes across the three platforms. However, the fact that the associated accounts have been active since late 2024 suggests a systemic exploitation of vulnerabilities in platforms’ moderation and data disclosure processes to spread specific messaging, thereby undermining civil discourse.

This report also exemplifies ongoing deficiencies in the data that platforms provide to independent researchers. The DFRLab found significant discrepancies within data that could be accessed via Meta’s Content Library and API compared to publicly accessible data from the platform. These differences—in terms of what accounts associated with the covert campaign targeting Moldova and Romania could be identified—represent a weak spot in companies’ transparency and accountability obligations.

Cite this case study:

Valentin Châtelet, “Cross-platform campaign accuses Moldova’s Sandu of meddling in Romanian elections,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), August 26, 2025, https://dfrlab.org/2025/08/14/cross-platform-campaign-accuses-moldovas-sandu-of-meddling-in-romanian-elections/.