Targeting the faithful: Pro-Russia campaign engages Moldova’s Christian voters

A coordinated online campaign relied on Christian traditionalist and anti-EU rhetoric to mobilize voters against PAS.

Targeting the faithful: Pro-Russia campaign engages Moldova’s Christian voters

Share this story

BANNER: A congregant films Archbishop Markel’s Mass with a smartphone at a church in Slobozia-Magura, Moldova, on September 6, 2025. (Source: REUTERS/Marton Monus)

In Moldova, where the Orthodox Church remains largely under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate, Russia-aligned networks exploited religious beliefs to influence the 2025 parliamentary vote. A cross-platform ecosystem on Facebook, YouTube, Telegram, and TikTok, which initially appeared to share generic religious content, was in fact targeting Moldovan voters with propaganda and electoral mobilization messages.

Moldova’s governing pro-EU party defeated its pro-Russian opponents in Sunday’s parliamentary elections, strengthening the nation’s push toward European integration while further distancing itself from Moscow’s influence.

On May 1, Jurnal.md published an investigation, Conspiracy in Bethlehem, exposing a Russian operation dubbed Matushka that used the Moldovan clergy to influence Christian voters ahead of the September 28 parliamentary elections. Audio recordings uncovered United Russia strategist Alexandr Ralnikov instructing priests during a March pilgrimage to Bethlehem, organized by the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission and sponsored by the Kremlin-linked non-governmental organization Evrazia. He urged them to build political parish-based youth cells for activism, stressing that recruits must oppose European Union (EU) integration, while promising financial and logistical support. A September 26 Reuters investigation also detailed Russian attempts to influence Moldovan voters via religious institutions.

A central component of the Matushka operation is the Salt and Light newspaper. On July 9, the DFRLab obtained a physical copy of the newspaper, which was widely distributed to households in a Chisinau neighborhood. The newspaper contained standard religious messaging, but what stood out was a contest offering “special prizes” that required participants to subscribe, via QR codes, to accounts on Telegram, Facebook, and TikTok.

The social media accounts, active across seven platforms, initially posted religious content, amplifying identical material such as quizzes, contests, and parish activities. Then, the content gradually shifted into urgent, defensive, and election-focused messaging.

An analysis of thematic and operational alignment identified sixty-seven channels tied to the Matushka operation across seven social media platforms. The network is most active on Telegram, with twenty-five channels and a total of 11,916 subscribers. It is followed by twenty-two channels on TikTok, which have a total of 21,632 followers, and eleven accounts on Instagram, which have a total of 3,725 followers.

A radial tree map of Matushka’s social media ecosystem. (Source: DFRLab via Flourish)

Election mobilization cloaked as religious messaging

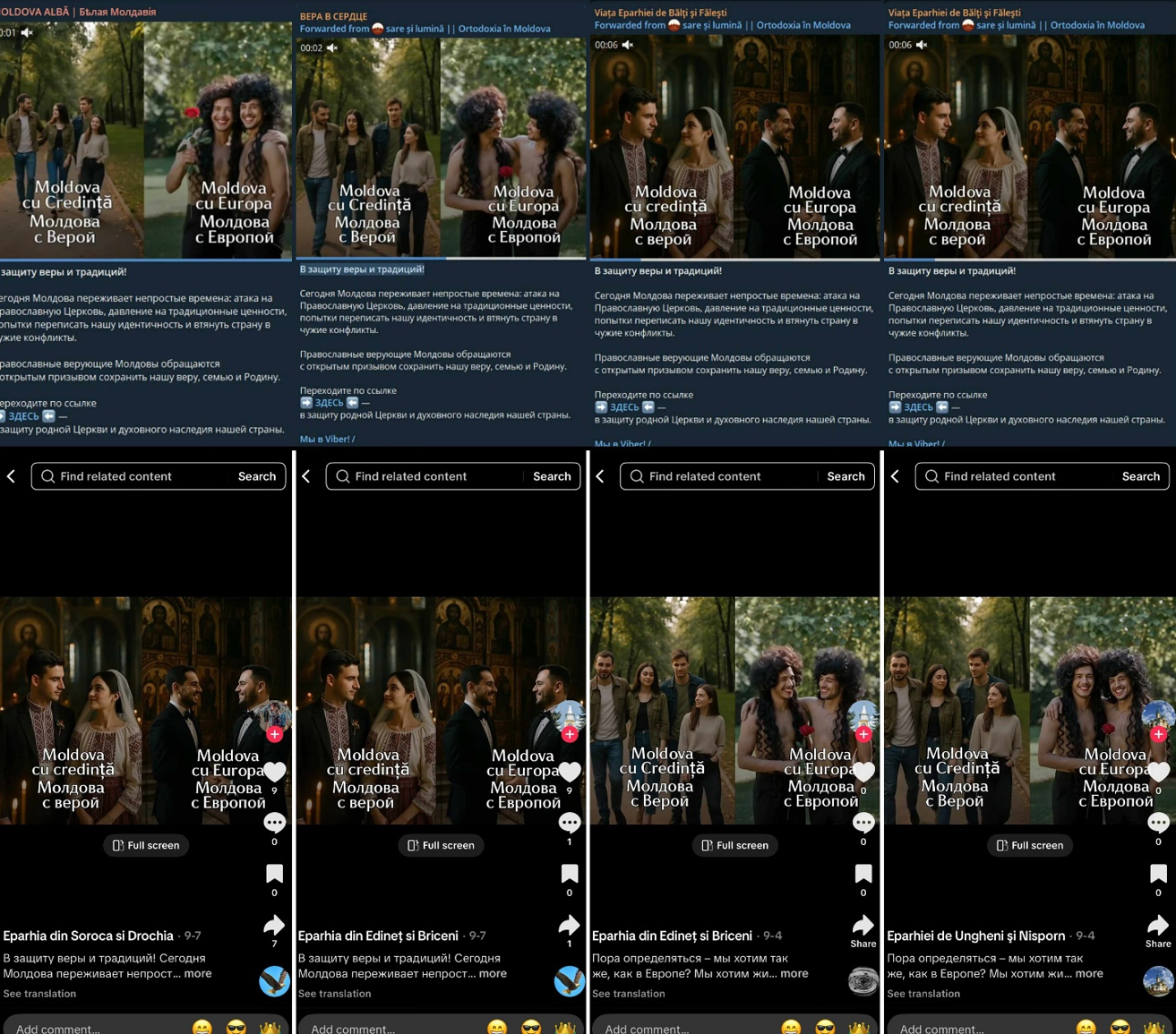

In September, one month before Moldova’s parliamentary elections, the Matushka network intensified its political messaging and anti-EU campaign with a series of posts comparing “Moldova with Faith” versus “Moldova with Europe.” The posts used side-by-side images, seemingly generated by artificial intelligence, to make contrasts of differing lifestyles and warn of attacks on the Church and traditional values. For example, one image showed an Orthodox wedding contrasted with a same-sex wedding, another image contrasted a generic group of young adults with a shirtless, long-haired gay couple, intended to frame European integration as a path of “moral decay” and Orthodoxy as the nation’s safeguard. These visuals circulated on multiple channels and pages across various platforms, including Facebook, Telegram, and TikTok.

All the posts across different social media platforms carried identical calls to action, urging users to defend “faith, family, and Motherland” by joining a Telegram bot channel, @trezeste_teMoldova_bot (Wake up Moldova), and a Viber group, funneling audiences from public social media spaces into closed platforms. The Telegram chatbot redirected users to mostenire.online, a website created on July 22 using a Russian IP address and hosting company. The site claims to “report on violations of believers’ rights” and asks users to submit such cases from their countries.

The messaging around “violations of believers’ rights” is a key component used to mobilize Moldovan Orthodox communities to vote for leaders who will “protect the Church” from “devastation.” The Matushka operation framed any pro-Western positioning as an urgent threat to faith and heritage. The “violated rights” narrative centered on the Bessarabian Metropolis, an Orthodox church tied directly to the Romanian Patriarchy rather than Moscow. Framed as a tool of Romanian nationalism and EU integration, these campaigns exploited fear of a “Romanian appetite to swallow Moldova” and questioned President Maia Sandu’s loyalty due to her dual citizenship.

The “violated rights” narrative was also echoed on the Matushka-linked Telegram channel @moldova_alba, which promoted a petition by Moldovans in Russia, accusing Chisinau of voter suppression for opening only two polling stations in Russia, versus dozens in Italy, in 2024. Hosted on moldovavote.ru (created in July 2025), the petition demanded polling stations in seventeen Russian cities, framing the issue as a form of discrimination.

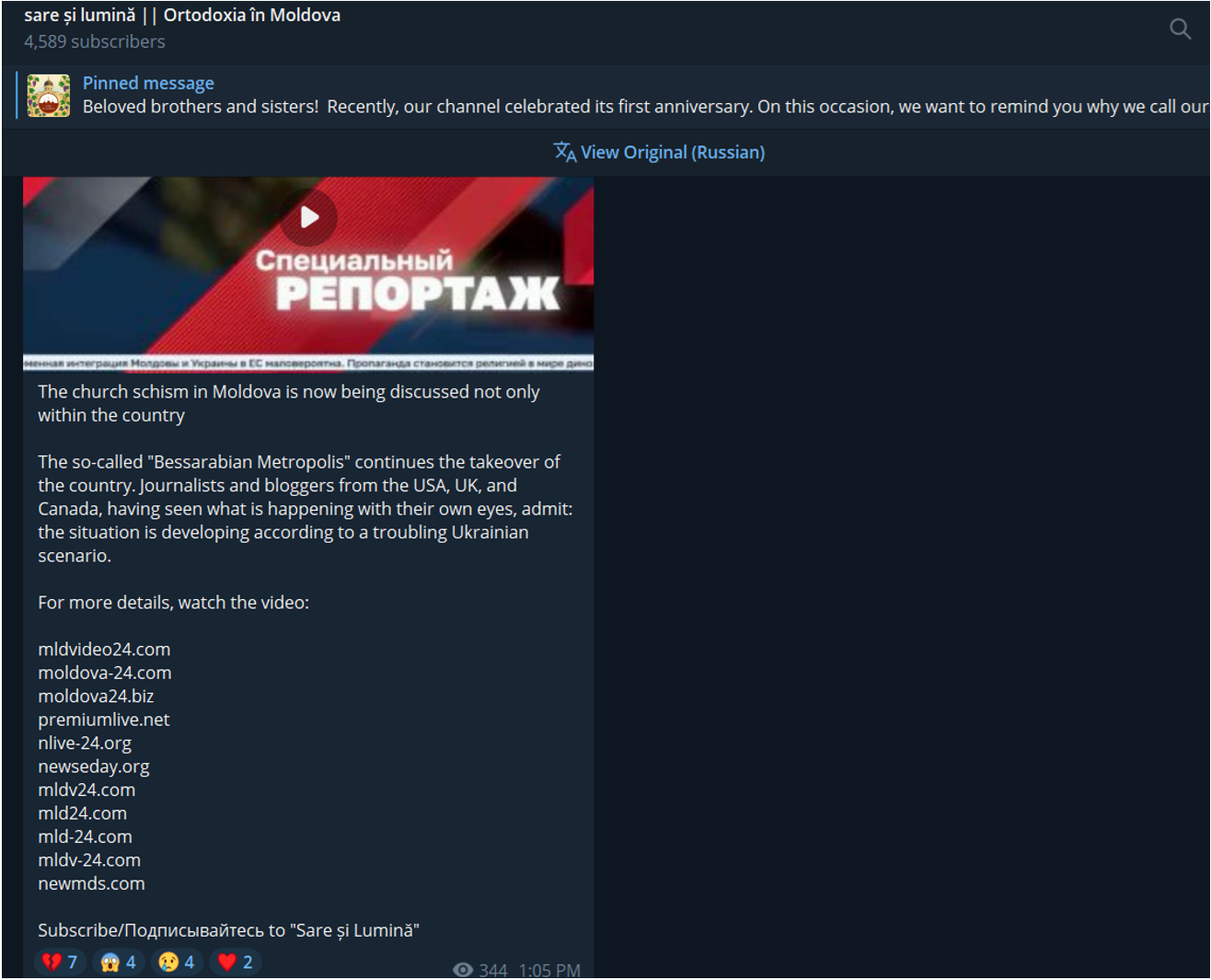

To reinforce the narrative that the Moldovan Orthodox Church is “under siege” by the pro-European government, Salt and Light invited a group of conservative bloggers from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada to Moldova. The visit was heavily promoted on their Telegram channel and amplified by Moldova24 (MD24), a television outlet previously identified by DFRLab as part of the Ilan Shor network and reliant on RT’s digital infrastructure.

This strategy aims to lend legitimacy to pro-Kremlin talking points by showcasing endorsements from foreign voices, framing the situation in Moldova as part of a broader geopolitical struggle. One post claimed: “The church schism in Moldova is now being discussed not only inside the country… Journalists and bloggers from the US, UK, and Canada, after seeing the situation with their own eyes, admit: events are unfolding according to an alarming Ukrainian scenario.” The campaign went further by attempting to appeal directly to US Vice President JD Vance to “intervene and help defend the traditional Church.”

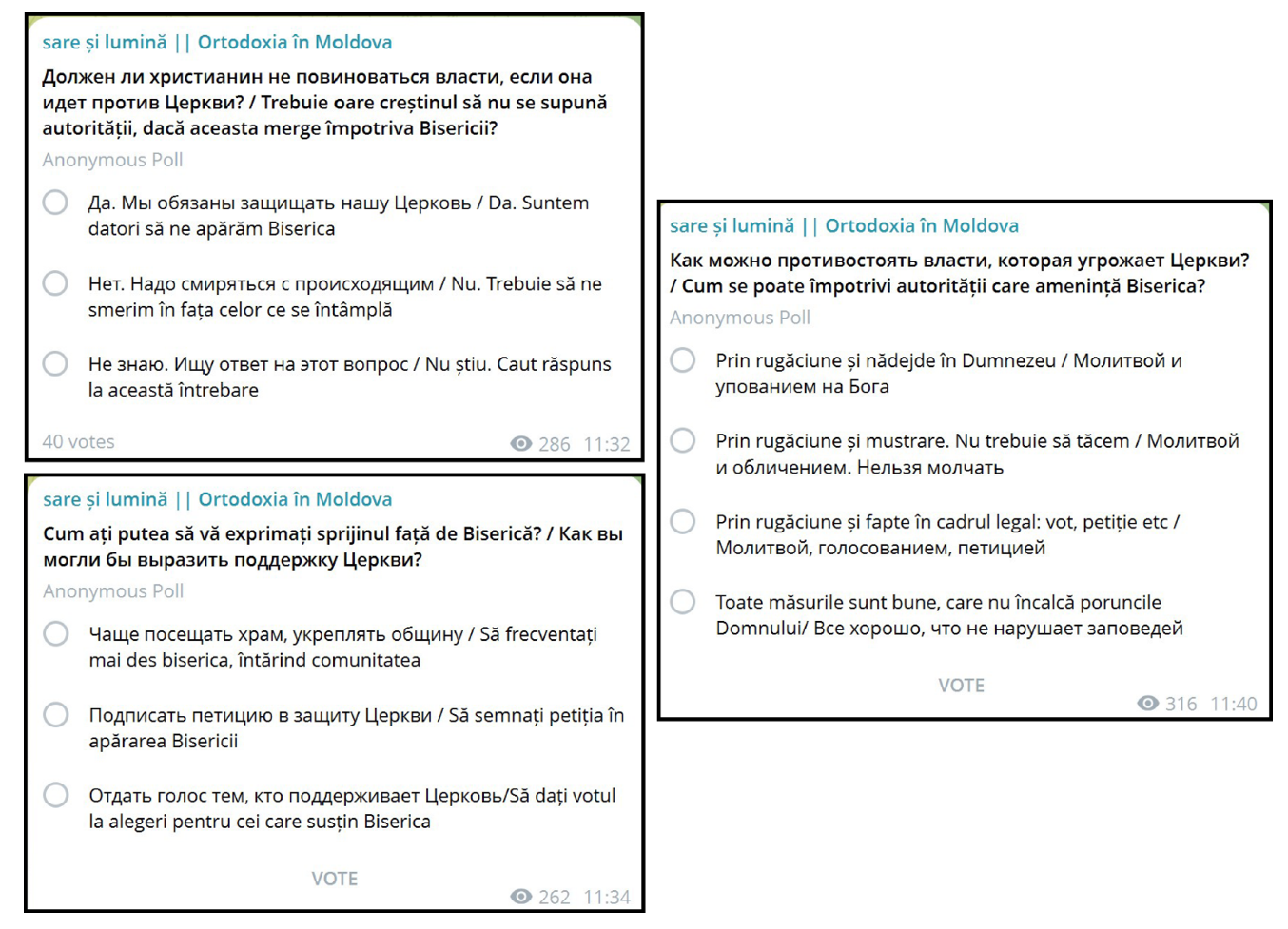

On September 11, Salt and Light posted three Telegram polls asking members whether Christians should resist the state authority if it “acts against the Church” and how believers can “defend” Orthodoxy. The polls repeatedly suggested political actions such as signing petitions and voting for candidates “who support the Church.” Framed as religious duty, these polls could be interpreted as a de facto form of political campaigning.

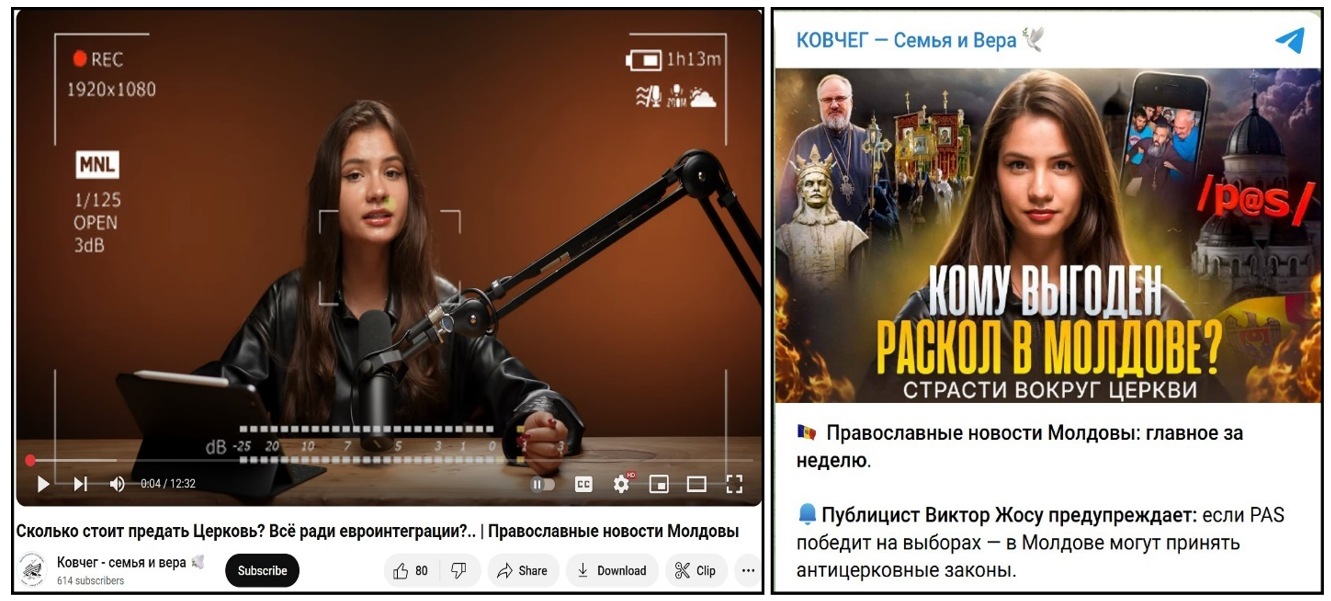

On YouTube, two Matushka channels, @sare.si.lumina and @kovchegMD, promoted political messages. In two videos, published on July 18 and July 25, the host cited Orthodox journalist Victor Josu, warning that “If the PAS party wins the parliamentary elections, anti-church laws may be introduced in Moldova.” The claim was amplified in the network’s Telegram channels. While claiming the Church should not endorse parties, the host urged the clergy to provide “moral guidelines” shaping political behavior and warned that a PAS victory would mean “usurpation of power” and the loss of real representation.

Beyond the calls against PAS, the Matushka network openly backed pro-Kremlin politicians. On July 3, Salt and Light posted a YouTube video where Archbishop Markel defended Kremlin-backed Gagauzia Governor Evgenia Gutul, calling the charges against her fabricated and urging prayers for her and other pro-Russian priests. In July and August, the network shared fifty Telegram posts featuring Markel’s statement.

Additionally, the account @pravmolmir promoted the Great Moldova Party leader Victoria Furtuna as a defender of traditional values, Orthodoxy, and Moldovan sovereignty. During the 2024 presidential election, Furtuna was supported by Shor’s network. Reports indicated that she received logistical and political support, and Victory Bloc activists encouraged voters to support her. Days before the September 28 vote, Furtuna’s party was banned from the race due to suspected illegal financing.

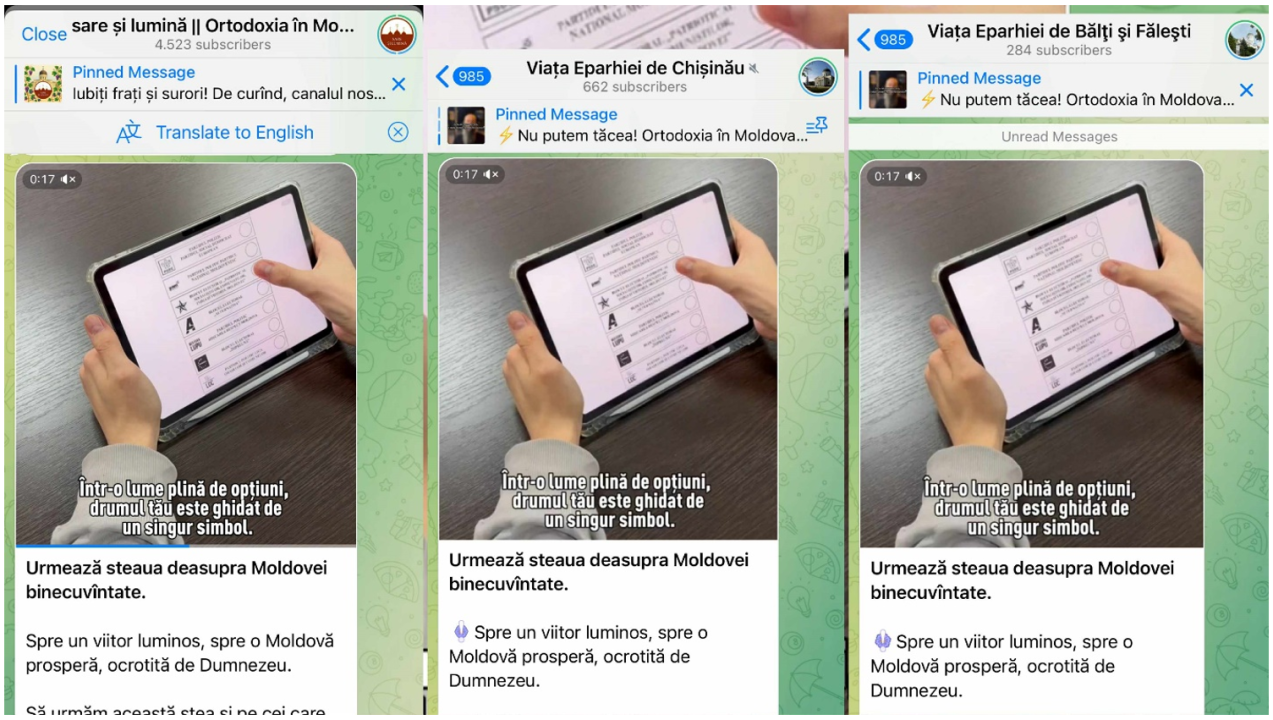

On September 26, the final day of the electoral campaign, the Salt and Light Telegram network posted a message urging Orthodox believers to “follow the star.” The post was accompanied by a video displaying a ballot paper with the vote cast for the “Patriotic” electoral bloc, comprised of the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) and the Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova (PSRM), which uses the star as its electoral symbol.

“Salt and Light” social media ecosystem

The Salt and Light newspaper promotes a QR code that links to a Facebook group named “Sare și Lumină Ortodoxia în Moldova” (Salt and Light Orthodoxy in Moldova), created on February 3. The group, with 904 members, describes itself as an “informational channel of the Moldovan Orthodox Church, covering faith, church, traditions, and current events.” It is currently managed by two accounts, Viorel Țesătorul and Paula Roussou, both of which appear to be inauthentic due to the absence of profile pictures, indications of stolen identities, and a lack of posting activity. Additionally, a Facebook page called Sare și Lumină, created on April 10, lists Russia and Ukraine as the primary locations of its managers. Further, Salt and Light actively runs Facebook ads to promote religious content and online contests. These contests often act as funnels, directing users to the group’s Telegram channel, where political messaging and coordination take place

It appears that the Salt and Light Facebook assets are managed from Russia and linked to Forma.ru, one of Russia’s most prominent Orthodox media outlets. An earlier, now inactive group with the same name (Salt and Light Orthodoxy in Moldova) was created on August 6, 2024, shortly before Moldova’s presidential elections. The group was administered by Matvei Kipnis, Asya Rigel, and Mișa Mișa and used identical visual branding to Salt and Light, indicating the current online platform may be a continuation of earlier efforts to mobilize Moldovan Orthodox communities online. The “about” section of Matvei Kipnis’s profile says he is from Yaroslav, Russia, is currently based in Moscow, and works as a podcast director at Forma. A reverse image search for Mișa Mișa’s photo identified him as Mikhail Kuznetsov, the senior editor of Foma’s website and social media projects. Kuznetsov also appeared in the earlier group under his real name. On September 3, 2024, Mișa Mișa announced that the project had “moved” to a new “address,” using the same logo now used by Salt and Light.

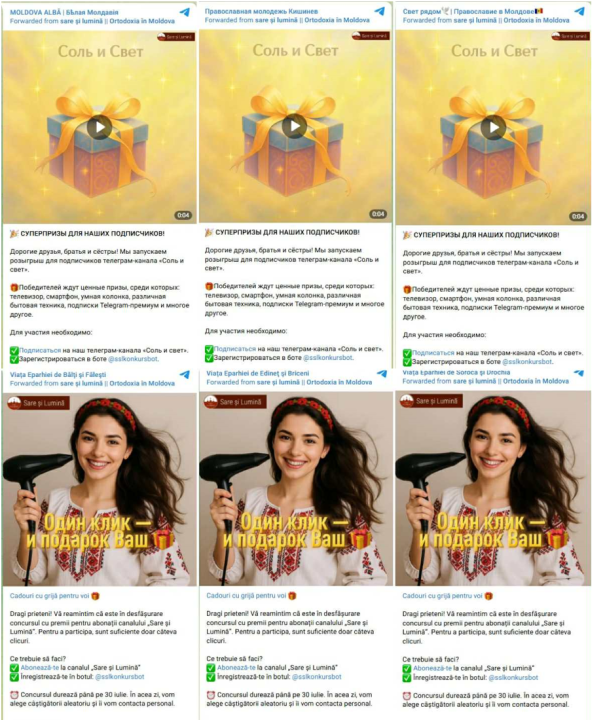

Another QR code in the Sare și Lumină newspaper directed users to a Telegram channel of the same name, which was created on June 27, 2024. As of September 12, it had 4,672 subscribers. The Telegram channel largely mirrored the Facebook page. The channel served as the hub of operation, as all contests in the paper and on social media directed people back to it. The channel frequently ran contests with small prizes for new subscribers, requiring entrants to submit personal data via a bot. The effort appears to be designed to collect data. Multiple religious channels promoted nearly identical contests, indicating a coordinated effort to expand Salt and Light’s audience.

Salt and Light also maintains an active presence on TikTok, YouTube, OK, and VK. On YouTube, where it has amassed 2,750 subscribers and over one million views, it publishes religious content, often sourced from Russian-language channels. The presence on multiple platforms, including Russian-owned social networks, highlights an effort to diversify outreach and engage with different demographic and linguistic audiences, particularly those already embedded in the Russian digital sphere.

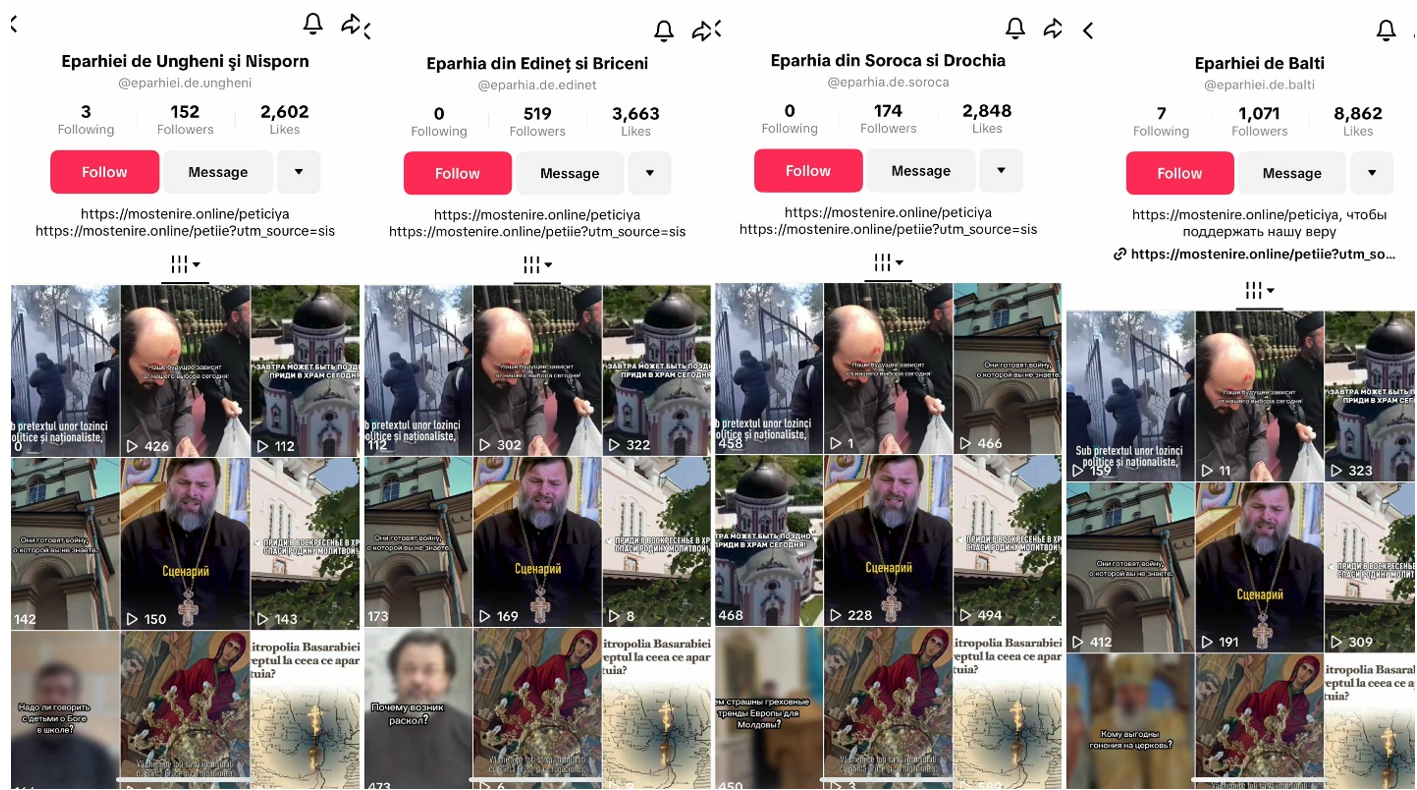

Further TG Stat analysis revealed that most outbound mentions from “Salt and Light” point to six additional Telegram channels associated with the six eparchies (dioceses) of the Moldovan Orthodox Church: Viata Eparhiei de Chisinau (The Life of the Diocese of Chișinău), Viata Eparhiei de Soroca, Viata Eparhiei de Ungheni, Viata Eparhiei de Edinet, Viata Eparhiei de Cahul, and Viata Eparhiei de Balti. The Viața Eparhiei de Chișinău was created on September 30, 2024, while the five other eparchial channels were created on the same day, October 2, 2024, just weeks before the 2024 elections in Moldova. These eparchy channels publish original content related to church life in their respective regions. Yet, they also appear to coordinate with the “Salt and Light” channel, particularly in amplifying shared messaging. This level of synchronization suggests the possibility of a centralized communication strategy.

The Eparchies’ social media presence shows strong signs of centralized coordination rather than organic, independent activity. On TikTok, their accounts use identical name branding and nearly word-for-word descriptions, each pointing followers to the same external site, mostenire.online. The content strategy is also synchronized: feed posts replicate the same visuals, text, and hashtags. This level of uniformity suggests that the channels could be managed from a common hub.

Youth movement

Other religious Telegram channels used similar tactics and appear to be connected to the Salt and Light network. In an audio recording published by Jurnal.md, a member of the Russian delegation outlines a detailed strategy for mobilizing youth around the church, promising funding, equipment, and training for social media activity and regular mobilization. This blueprint mirrors activities on the Telegram channel @KovchegMD, launched on March 31 and identified by DFRLab as a key pro-Orthodox youth hub in Moldova.

KovchegMD also operates a TikTok account (2,207 followers and 138,000 likes), an Instagram page (347 followers), and a YouTube channel (991 subscribers and 163,934 views), illustrating its cross-platform strategy. The group produces Instagram Reels and TikTok videos to attract young people, while organizing festivals, barbecues, football games, and weekly gatherings at the church. These social activities closely resemble the model outlined in the leaked recordings.

TikTok posts from KovchegMD feature a recurring group of young organizers shown as relatable peers, singing at barbecues, playing guitar at festivals, or casually discussing faith. The same faces also appear in Salt and Light videos, pointing to shared personnel and coordination. This overlap suggests that KovchegMD is not an isolated youth project but instead could be part of a broader influence network.

The same young man, identified as Misha, appears in an earlier Salt and Light post dated April 19, where he introduced himself as a member of “Orthodox Youth.” Misha, along with several other young people active on KovchegMD, participated in a flash mob organized in support of pro-Russian Archbishop Markel. His statements are frequently amplified by channels like Salt and Light and @pravmolmir, where they are circulated dozens of times to reinforce the narrative that Orthodoxy is under threat.

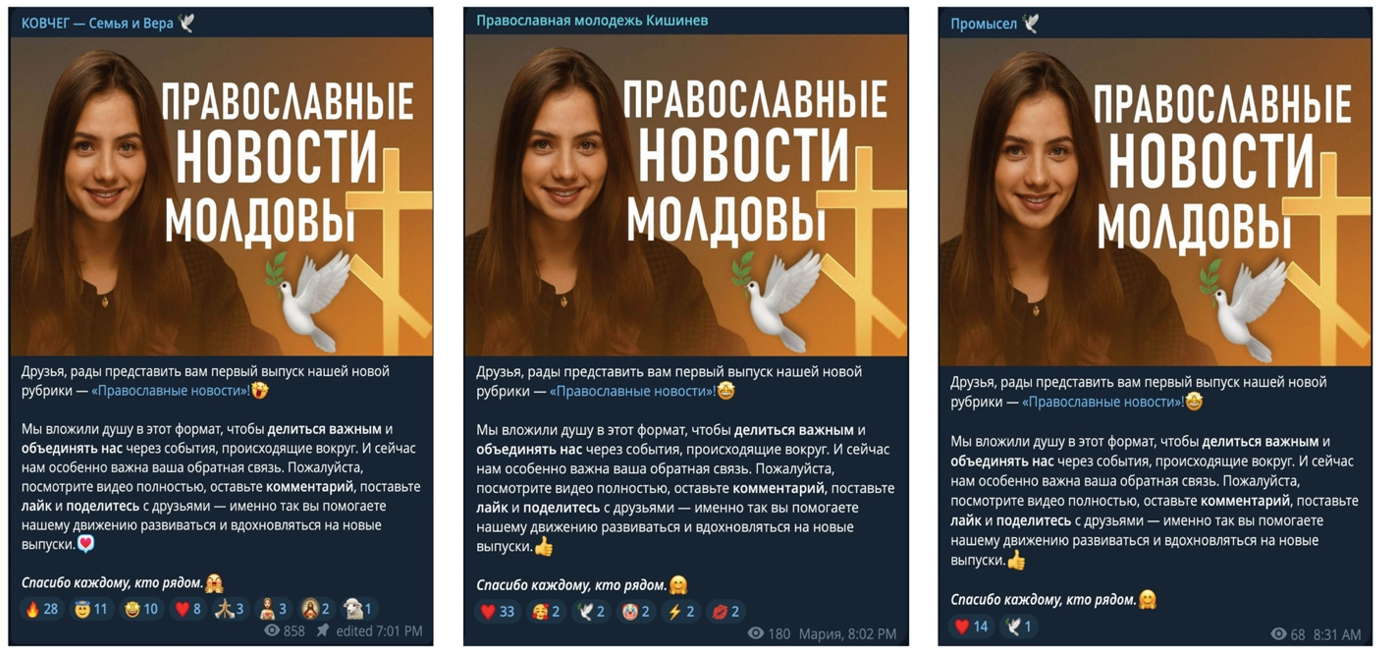

On July 4, KovchegMD posted on Telegram about the launch of the first episode of their new YouTube series, “Orthodox News.” The format aims to share social, religious, and political updates to build a community around current events. Hosted by a young woman named Anastasia, the series streams on the YouTube channel of KovchegMD. Interestingly, the same post was published in two other Telegram channels, Youth Orthodox of Chisinau and “Промысел” (Divine Providence), announcing the launch of “their new program.” Earlier, representatives of Youth Orthodox of Chishinau were seen distributing the printed newspaper of Salt and Light in Moldova, which underscores its connection to the broader Matushka network. The use of identical posts across three separate channels strongly suggests interconnection, while the frequent reposting of Orthodox News links throughout the wider network points to a deliberate cross-sharing strategy.

One day before the elections, Kovcheg announced that YouTube had deleted their channel, framing it as an attack on the Church and assuring followers that “the truth cannot be deleted — the episodes will continue to be released” and that they would always be available to watch on Telegram channels.

The DFRLab’s analysis of Kovcheg revealed additional Telegram channels with comparable content and messaging strategies, all geared toward engaging young Moldovan audiences through Orthodox narratives. These include Orthodox Youth of Chisinau, which also runs active Instagram and TikTok accounts; Orthodox Moldova; and Light Nearby | Orthodoxy in Moldova. Like KovchegMD, these channels post similar social content, ranging from youth gatherings and contests to traditional celebrations.

Ahead of Moldova’s 2025 elections, Russia expanded the Matushka operation, utilizing church structures as a cover for its political objectives. The Salt and Light ecosystem reveals how coordinated channels mix religious content with pro-Kremlin messaging. By incorporating youth initiatives like Kovcheg to online campaigns, pilgrimages, and charity events, Moscow aims to build a digitally savvy, religiously motivated youth base that can influence Moldova’s electorate in line with Kremlin interests.

Cite this case study:

Victoria Olari, Givi Gigitashvili, Sopo Gelava, “Targeting the faithful: Moldovan Christians caught in pre-election campaign,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), September 30, 2025, https://dfrlab.org/2025/09/30/targeting-the-faithful-moldovan-christians-caught-in-pre-election-campaign/.

A public task financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland within the frame of ‘Public Diplomacy 2024-2025: The European Dimension and Countering Disinformation’ contest. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the official positions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.