How CSSAs reinforce official narratives to expat Chinese students on WeChat

The DFRLab analyzed WeChat articles from Chinese Students and Scholars Associations across the US, UK, Canada and Australia.

How CSSAs reinforce official narratives to expat Chinese students on WeChat

BANNER: (Source: Budrul Chukrut / SOPA Images/Sipa USA via Reuters Connect)

DFRLab’s August 2022 report on Chinese discourse power highlighted the real-world mobilization capabilities of Chinese Students and Scholars Associations (CSSAs) in rallying Chinese university students to participate in nationalist demonstrations abroad. This case study — one of two in a series on CSSAs and WeChat- expands on the research of CSSA’s political and influence activities on their surrounding academic and social communities through data analysis of their presence and posts on WeChat.

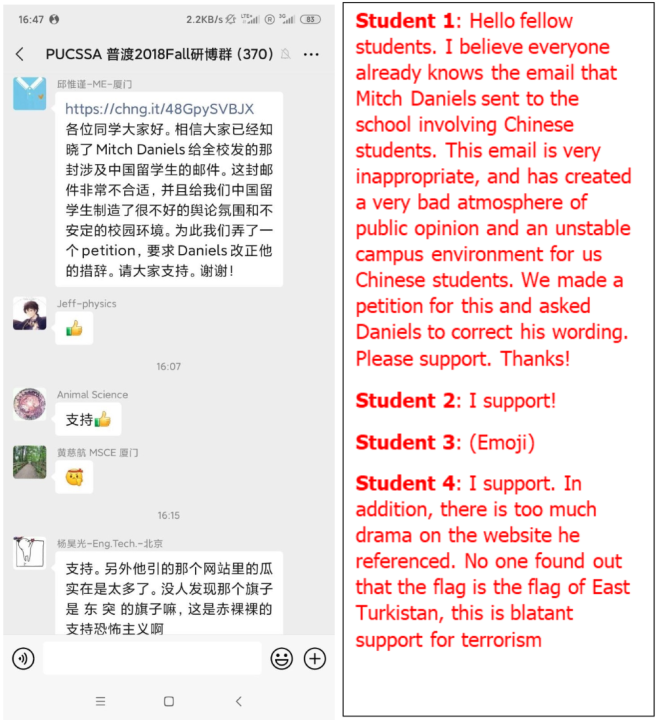

All CSSAs use the Chinese messaging platform WeChat as their main line of communication. For example, conversations within Purdue University’s CSSA were lively in wake of news accusing the Chinese Ministry of State Security of intimidating a dissenter’s family after reports by other Chinese students on campus. Since private CSSA WeChat groups are inaccessible and leaked screenshots are rare, though, the DFRLab chose WeChat articles as the primary source of data for this analysis. WeChat articles are published by “official accounts” on the platform, which function like Facebook pages. Articles published by CSSAs offer researchers glimpses into the opaque student groups.

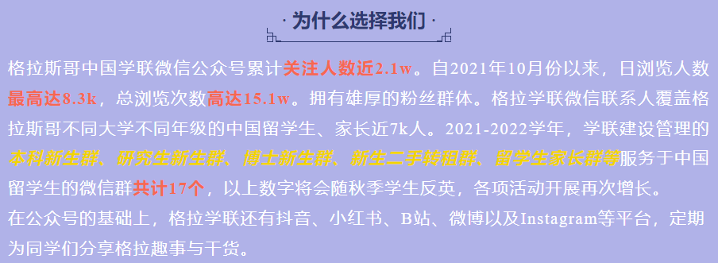

CSSAs have extensive outreach efforts on WeChat. Using the University of Glasgow CSSA as a sample, it detailed audience exposure metrics that were publicly unavailable in a “looking for sponsorships” article. According to a post on January 18, 2022, the official account for the Glasgow CSSA had nearly 21,000 followers, daily views up to 8,300, and 151,000 total views. Its community had 7,000 people, including students’ parents. The post also stated that there are seventeen private WeChat groups under the University of Glasgow CSSA network for undergraduates, graduates, and beyond. The CSSA can also be found on many other social media sites such as Douyin, Xiaohongshu, and Bilibili.

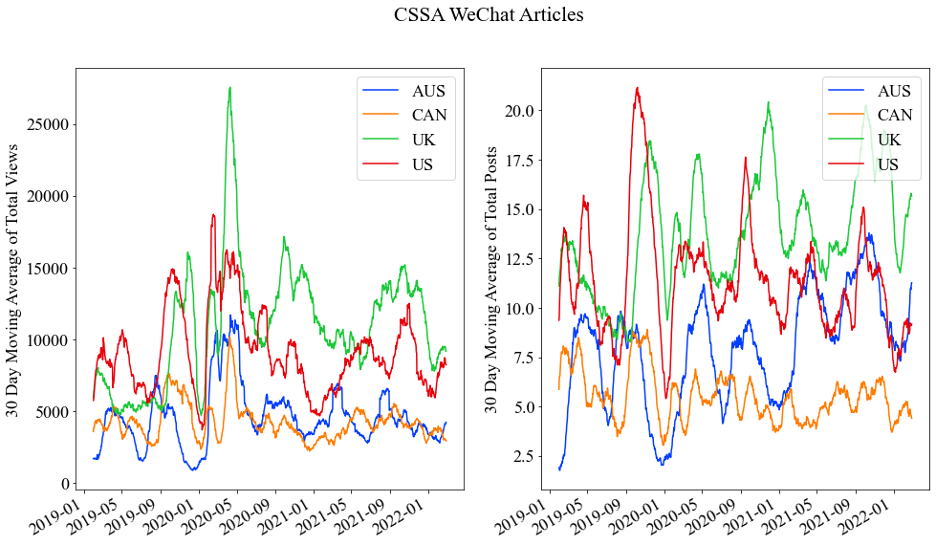

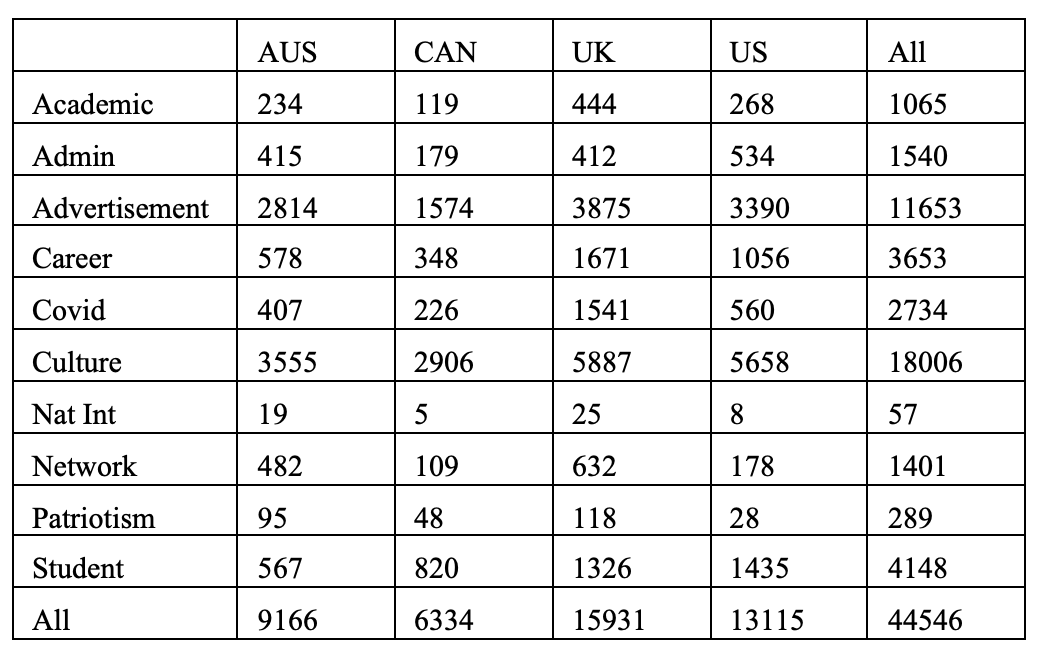

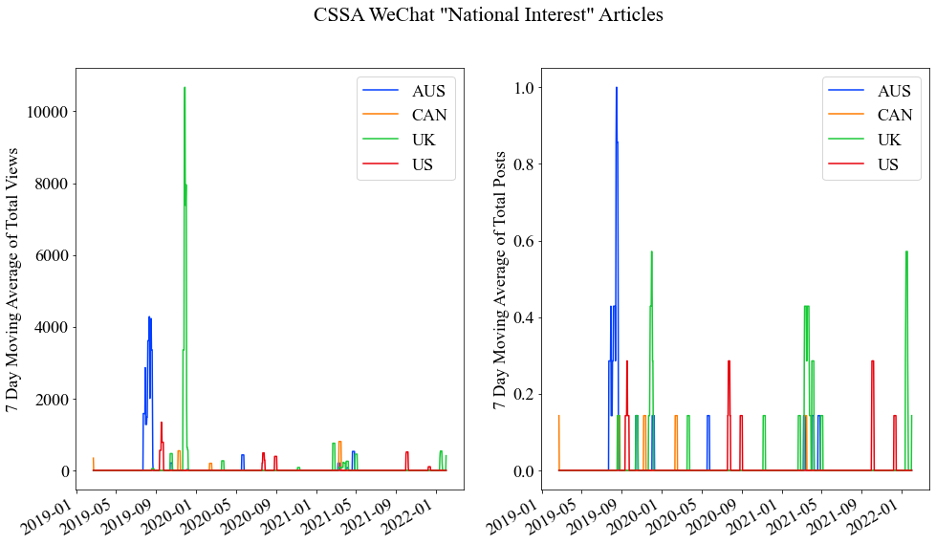

The DFRLab analyzed WeChat articles published between January 2019 and March 2022 by forty-four CSSAs evenly split across the US, UK, Canada, and Australia for a total of 44,546 articles. The eleven CSSAs sampled per country prioritized universities with large Chinese student population; we were also mindful to select CSSA’s representative of each country’s academic and geographic diversity.

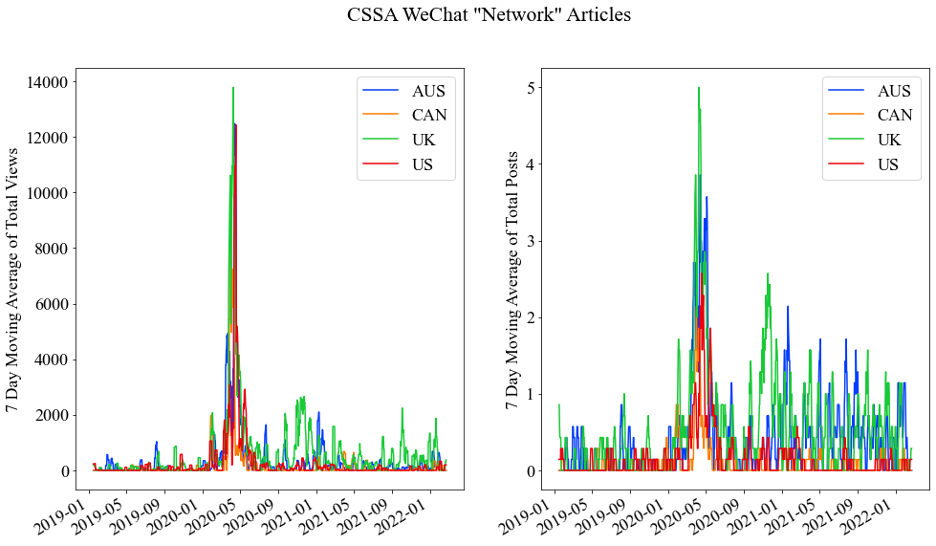

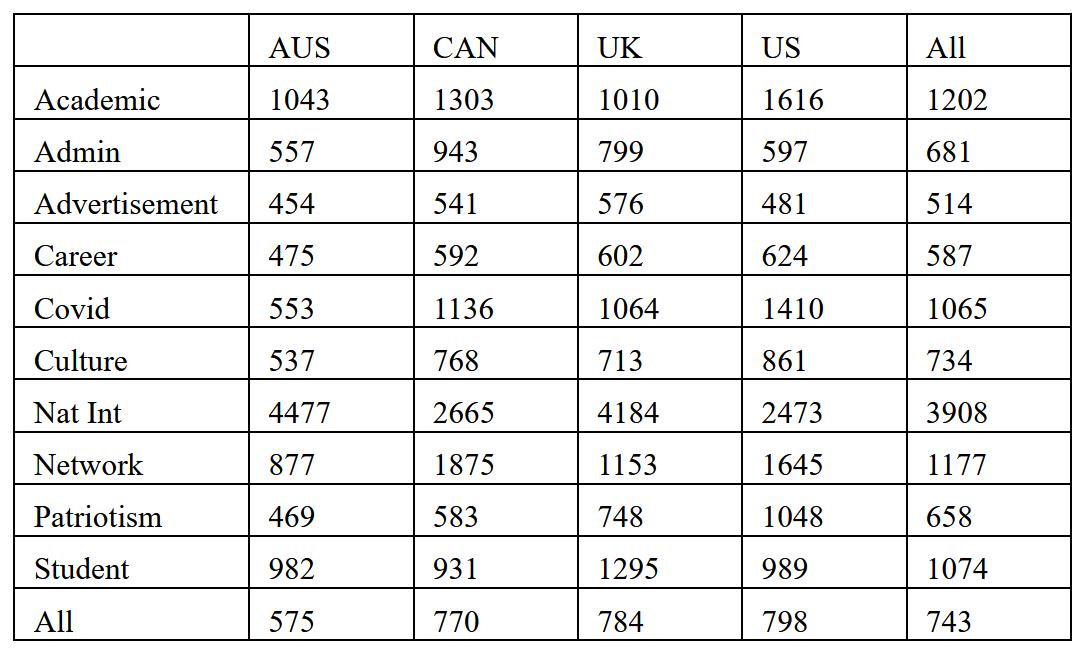

The number of posts published by CSSAs fluctuated cyclically with the school year. Early 2020 marked a spike in both post count and post views due to the disruption caused by the pandemic. The two graphs above suggest the UK and US CSSAs engaged with more members than those in Canada and Australia. The DFRLab identified common types of posts and organized them into ten overarching categories:

- Academic: Academic news and conferences

- Admin: CSSA organizational news

- Advertisement: Sponsorships and promotions from businesses

- Career: Career fairs and employment guides

- Covid: Pandemic-related news

- Culture: Social events or lifestyle articles

- National Interest (Nat Int): News related to safeguarding China’s national interests

- Network: Articles involving the Chinese embassy and other stakeholders

- Patriotism: Articles promoting loyalty and patriotism to the “motherland”

- Student: Student life news and guidelines

It was impractical to individually filter through each of the 44,546 articles to tag those of interest. Instead, DFRLab manually labeled 1,700 articles and used their titles to train a logistic regression classifier that categorized the remaining articles into the ten separate categories. The classifier had an overall accuracy of 70 percent when measured against a testing set; articles in the national interest, network, and patriotism categories were reviewed to remove as many false positives as possible. The labeled posts then became a starting point for further research.

Articles in the “Culture” category made up over 40 percent of the total, suggesting CSSA members spend the most time planning and participating in cultural activities. Events include everything from singing contests to cooking competitions, with the biggest event being the Spring Gala for Chinese New Year. These cultural activities are cash drains that require substantial outside financial support. For reference, UC Berkeley CSSA publicly released portions of its financials after accusations of embezzlement by member students in 2021. Despite the pandemic lockdowns, the CSSA had high expenditures of roughly $40,000 for the 2019–2020 school year, even though the CSSA claimed it was much less than that of the previous school year.

Bridging the funding gap is the role of advertisement-related posts — the second-largest category, representing 26 percent of the total. Sponsors were vital to each year’s grand production of the Spring Gala, and CSSAs actively courted partnerships. Local Chinese businesses and even established Western companies paid for advertising on CSSA WeChat pages. This created potentially reputation-damaging juxtapositions. For example, the logos of major Canadian banking and telecommunication companies were showcased in a University of McMaster CSSA article reporting a Uyghur rights talk to the Chinese embassy, underneath a so-called “nine-dashed line” map presenting disputed islands in the South China sea as Chinese territory. Chinese-run academic tutoring and career consultancy services also partner with CSSAs to sponsor advertisements disguised as career guides. Funding from these businesses complimented the support from the local Chinese embassies and consulates.

A small portion of articles in the “Admin” category concerned greater student union politics. Due to the aforementioned article in 2019 about the McMaster CSSA acting as an informant to the Chinese embassy and shouting down the Uyghur activist, the university’s student union revoked the CSSA’s official club status, citing that it posed “a significant threat to the freedoms, safety, and security of students on campus.” Two years later, the CSSA wished to be reinstated. It urged its members to sign up for the student union’s general assembly where a motion to reestablish the CSSA as a club could be proposed. Unfortunately for the CSSA, not enough members participated to meet the required minimum of votes.

Additionally, UC Berkeley CSSA and Monash University CSSA have articles promoting candidates for their schools’ student unions. Berkeley CSSA’s candidates were exceedingly successful in their elections: the CSSA has endorsed two student union senate candidates every year since 2020, all of whom have been elected. In turn, these senators posted recruitment ads for their offices on CSSA pages, and rarely on Facebook. These senators did not hold executive positions in the CSSA prior to their elections, but the DFRLab found that one senator was an organizer of a CSSA Spring Gala, suggesting a certain level of seniority. While the DFRLab has not found evidence of these senators sponsoring pro-Beijing resolutions in the student union, in recent years there was a notable lack of resolutions in support of or even mentioning the foremost China-related issues, such as the Hong Kong Protests and Uyghur rights when the student unions were clearly vocal on other international concerns, such as criticizing the government of India, showing solidarity with the people of Afghanistan, and defending the human rights of Palestinian children. Nevertheless, these examples show CSSAs actively involved in wider student politics.

“Network” articles primarily relate to matters involving the local Chinese embassy. Public interactions between CSSAs and the embassies were low until the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In early April 2020, Chinese embassies and consulates distributed free “health packs” to Chinese university students, generating goodwill in the CSSA community. Embassies in the UK and Australia have remained in frequent contact with CSSAs since April 2020, with surveys for personal contact information, additional health packs, and reminders to stay safe and avoid scams making up the bulk of these communications. This shows added emphasis and engagement by these two embassies compared to their counterparts in the US and Canada to influence the Chinese student population.

If cultural activities, career opportunities, and material benefits are what the CSSAs provide their members, then being loyal to the Chinese Communist Party and defending its policies abroad are what they expect from members in return. Although articles instilling patriotism had lukewarm receptions in terms of article views, national interest articles — those defending Beijing’s policies on issue areas such as Hong Kong or Xinjiang — reached significantly higher audiences (see Table 2, above). This reflects the importance members placed in responding to debates and protests that they view undermined China’s national sovereignty.

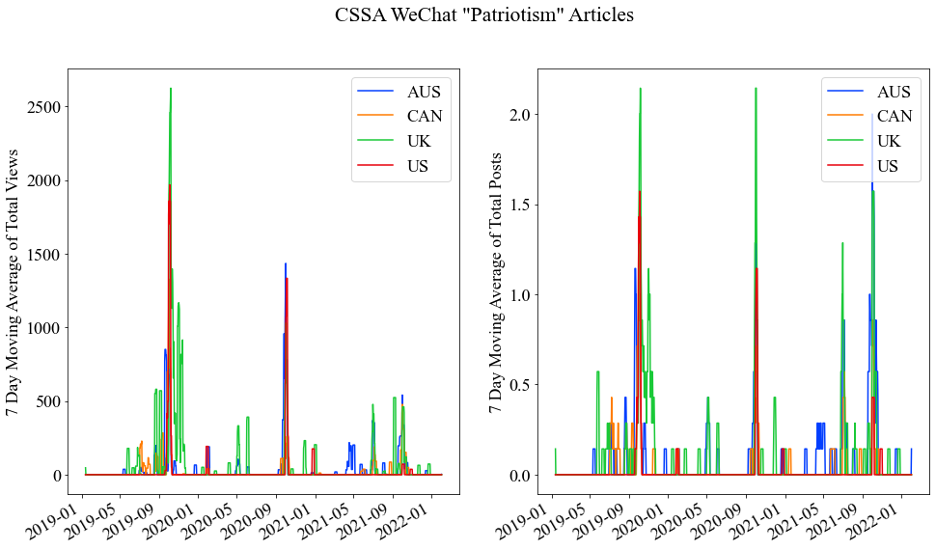

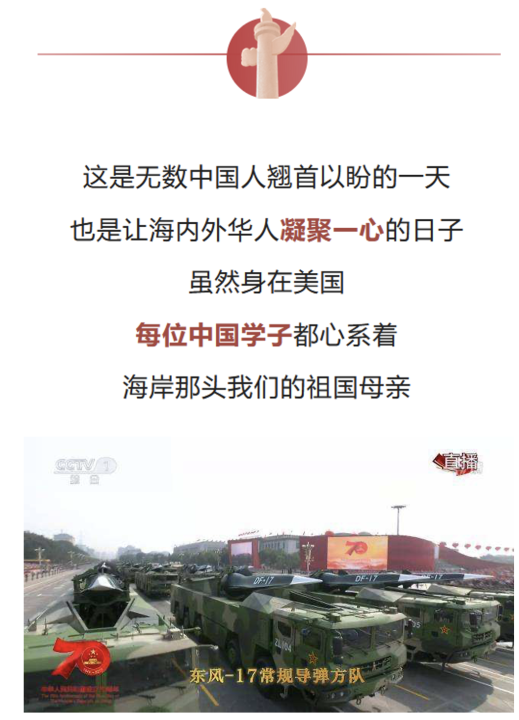

CSSAs publish articles instilling the patriotic spirit leading up to each Chinese National Day on October 1, with writing styles and expressions mirroring those of Chinese state media. The graphs above show the view count of articles during each National Day falling when the post count remained constant. This may suggest that Chinese students are growing indifferent and more apolitical. 2019’s National Day being the 70th anniversary of PRC’s founding heightened enthusiasm for the holiday, which is the likely explanation for its popularity compared to that of other years.

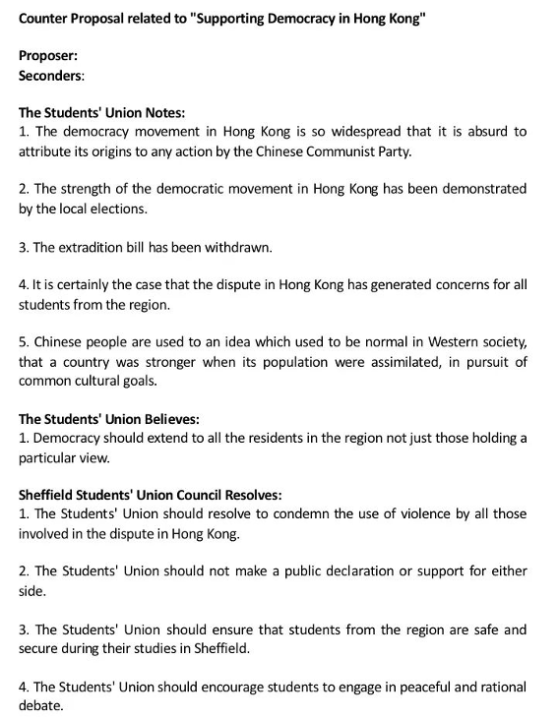

In terms of posts relating to national interests, the most widely circulated political posts regard the 2019 Hong Kong protests. By country, the most widely read posts came from the UK CSSAs, with one from Sheffield CSSA topping the list at 42,000 views, many multiples over the current count of CSSA members. The post on November 26, 2019 called for the members of the Sheffield CSSA community to attend a hearing by the student union on enacting a proposal supporting the democracy movement in Hong Kong. Because Beijing framed the Hong Kong protests around radical separatists, the CSSA wrote a counter proposal that paralleled positions held by the Chinese Communist Party. The counter proposal absolved the CCP of any blame for instigating the initial protests, instead featuring condemnations of violence by protesters.

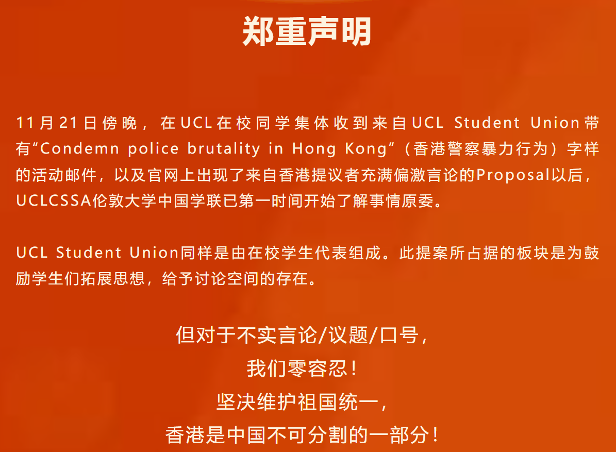

On the same issue, the University College London (UCL) CSSA reacted forcefully to a newsletter from the broader university student union that called on UCL students to “condemn police brutality in Hong Kong,” receiving more than 23,000 views. The UCL CSSA lodged a complaint with the university, stating that the student union should not take sides on the Hong Kong issue. The CSSA stated it would “continue to communicate with the student union, under the premise of protecting China’s national interests and student interests.” The UCL student union apologized, clarifying that the newsletter should not have been sent out and that it had no official position on the topic. It also clarified that in order for a statement to become official student union policy, a debate would first have had to have been held on the issue, but this did not take place. The CSSA had thus interpreted the email regarding the proposal as representing official student union policy and objected to it.

On China’s National Day, the University of Manchester CSSA hosted a patriotic rally, with students singing the national anthem and waving Chinese flags to counter the “anti-China separatist movement” in Hong Kong. Other celebration events included a banquet in Edinburgh held by the local consulate with involvement from the local CSSA, which was covered by Chinese state media. In a separate event, the CSSAs were present in a celebration for the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CCP alongside the consulate and the Communist Party of England. The CSSA was able to mobilize 150 students to attend this political event, which speaks to its strong organizational capabilities. In 2021, tensions between the mainland and Hong Kong culminated in a fight in London’s Chinatown. Radio Free Asia later reported that pro-CCP participants in the fight had Beijing ties.

Another example of “safeguarding national interests” included the University of Glasgow CSSA’s discovery of Taiwan being categorized as a country on the university website. After a student reported the discovery to the CSSA, it promptly complained to the administration, which subsequently changed the terminology on the website. Since CSSAs are closely aligned with local Chinese embassies, ideas and policies that differ from state interests are met with hostility.

The sensitivity of the CSSAs to these issues mirrored the sentiment of the Chinese government at the time, especially around Hong Kong and Taiwan. For example, in October 2019, China’s state broadcaster and Tencent stopped airing NBA basketball games from the United States after an NBA team manager tweeted support for the Hong Kong protests. The same month, luxury retailer Tiffany & Co. apologized before discontinuing a digital ad that inadvertently referenced a Hong Kong protest symbol. Swarovski, Versace, Coach, Calvin Klein, Marriott, and others were also attacked by the Chinese government for listing Hong Kong and/or Taiwan as separate countries on their websites or in company campaigns.

CSSAs have grown into sizable communities that have great mobilization power. CSSA members are encouraged by their local embassy to be “model students abroad,” as defined by the state. This includes showcasing patriotism, protecting national interests, and staying in line politically. In turn, these students receive various material benefits from the embassies. Members have a sharp eye for things that are deemed politically hostile by mainland standards, bringing the offending item to the CSSA’s attention to have them “corrected,” as shown in the previous examples. As such, CSSAs’ ability to organize passionate counter-protests and nationalistic rallies make them a major pro-Beijing political force abroad.

For additional analysis of CSSA WeChat narratives, please read our companion piece, “WeChat channels keep Chinese students in US tied to the motherland.”

Cite this case study:

“How CSSAs reinforce official narratives to expat Chinese students on WeChat,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), August 31, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/how-cssas-reinforce-official-narratives-to-expat-chinese-students-on-wechat-fec88c85f2b.