Colombian PR firms used Facebook ads to spread disinfo on presidential candidates

Facebook ads, websites, and fringe media spread disinformation about several candidates, including President Gustavo Petro.

Colombian PR firms used Facebook ads to spread disinfo on presidential candidates

Share this story

BANNER: Gustavo Petro receives the presidential sash during his swearing-in ceremony in Bogota, August 7, 2022. Petro was among several candidates targeted by so-called “disinformation for hire” campaigns. (Source: REUTERS/Luisa Gonzalez)

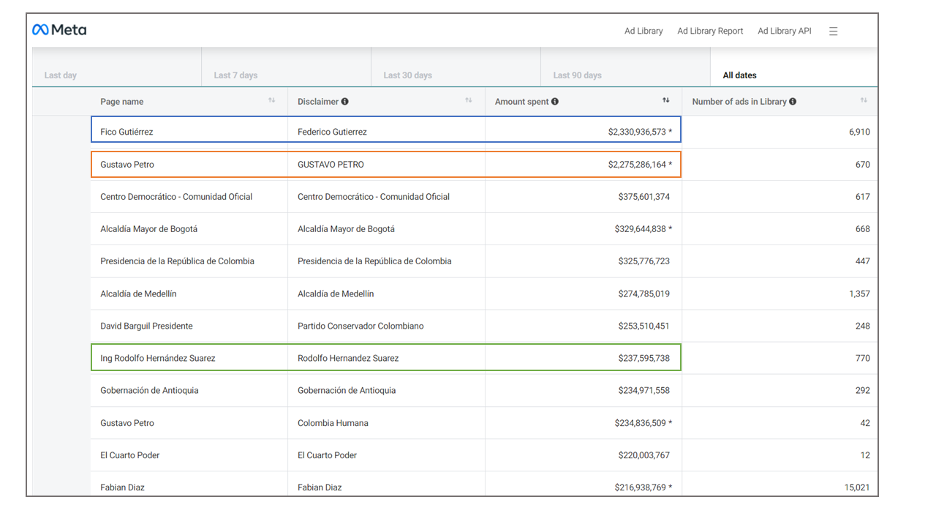

In the run-up to Colombia’s presidential election, Facebook ads posted by coordinated social media networks, with links to so-called “disinformation for hire” marketing firms, targeted a wide spectrum of presidential candidates and political leaders. The DFRLab analyzed seemingly inauthentic campaigns that paid for Facebook and Instagram ads ahead of the first and second round of the Colombian elections, held on May 29 and June 19, 2022, respectively. We found that Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro, was the candidate most targeted by the ad campaigns.

During the first round of voting, one network used hateful, misleading, and false content to criticize political leaders, including former Colombian presidents Álvaro Uribe Vélez and César Gaviria Trujillo, and the current leaders of the political parties Centro Democrático (CD) and Partido Liberal. The ads, which bear the hallmarks of a previous “disinformation for hire” campaign identified by the DFRLab, did not target the right-wing candidate Federico Gutiérrez or independent Rodolfo Hernández. However, Hernández was targeted November 27-29, 2021 by a set of 18 ads posted by Colombia LIBRE, an inactive Facebook page previously detected by the DFRLab as having connections to a “disinformation for hire” campaign.

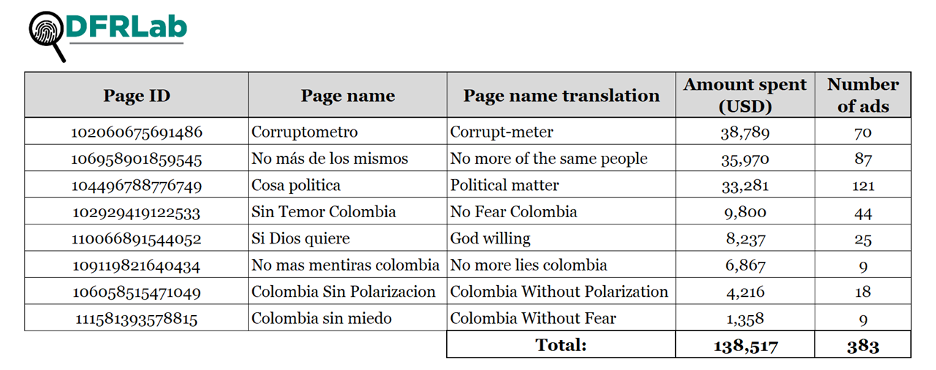

In the second round of voting, three campaigns used Facebook and Instagram ads to link to alternative websites and fringe media that attacked Hernández or Petro. One of the highest spending campaigns, which targeted Petro while supporting Gutiérrez and Hernández, paid $138,500 for ads. For comparison, Hernandez’s official Facebook page spent $53,000 on ads, Petro’s Facebook page spent $506,000 on ads and the Gutiérrez Facebook page spent $518,000 on ads. For further context, the amount the network invested in the social media ads could have covered the monthly minimum wage for more than 620 people in Colombia.

The DFRLab identified connections between the marketing firm Global System Company and one of the networks that became active during the second round of voting. Global System Company was the advertiser behind Notifreshco ads, a still-active Facebook page and Instagram account that posts content in support of Petro as elected president.

While Meta removed some of the identified ads, and others were deleted by network operators after the presidential elections, most of ads identified by the DFRLab remained active and received thousands of impressions in the run-up to Colombia’s presidential election. In response to this investigation, Meta removed five fake accounts and two Facebook pages for violating Meta’s inauthentic behavior policy.

The social media and website content analyzed in this report shows that “disinformation for hire” played a role in the 2022 Colombian election. Connections could be found between Colombian marketing firms and social media networks that attempted to influence the election by spreading messages of polarization and fear.

First round of elections

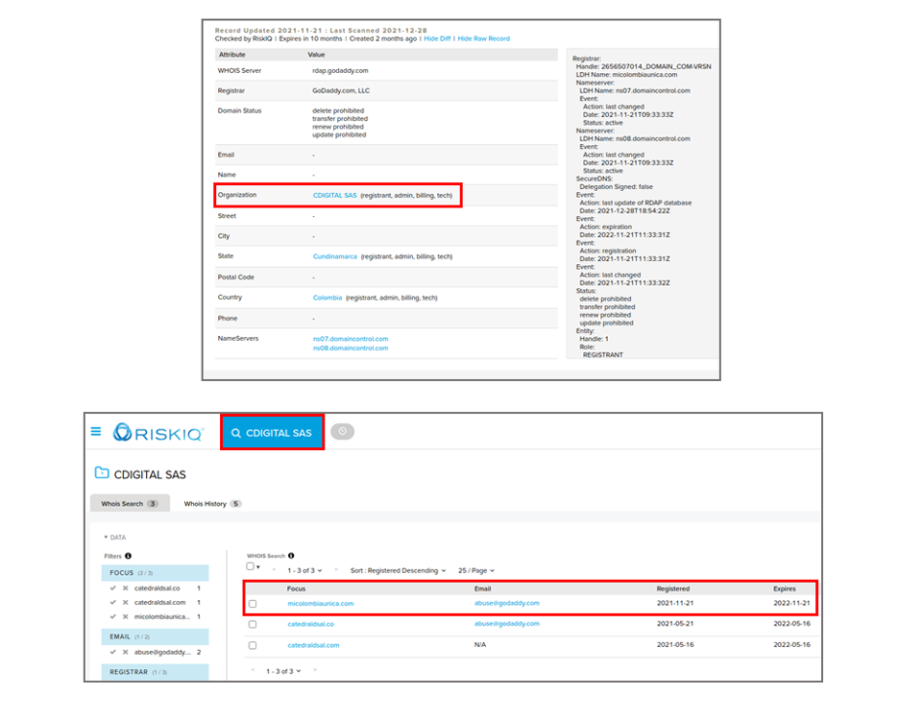

The DFRLab previously identified connections between two marketing agencies, Cdigital SAS and Marketing Digital Strategy, and social networks that attempted to influence the primary elections of coalitions –known locally as inter-party consultations– held on March 13.

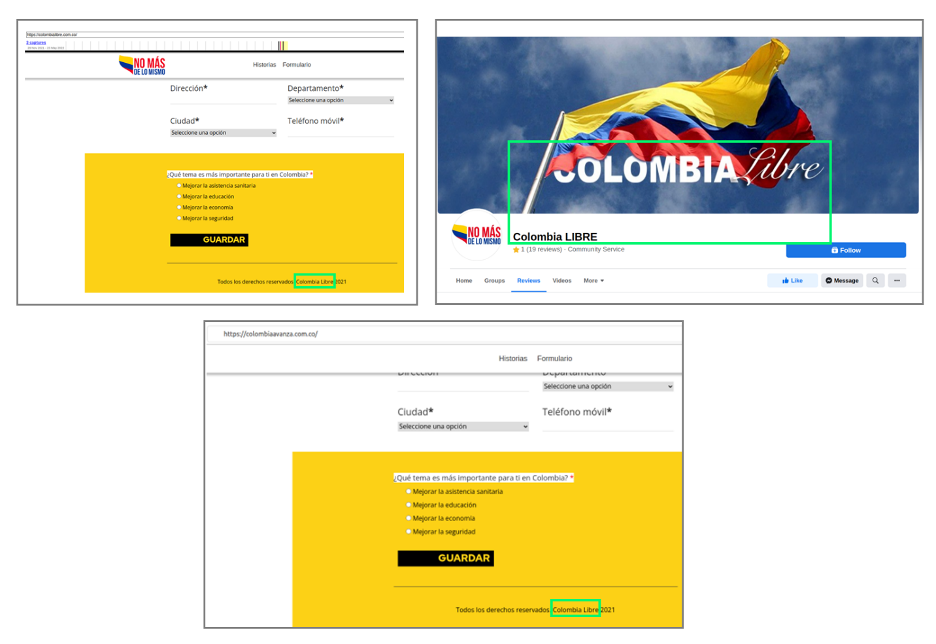

In our previous investigation, we found that during the five-month period between September 8, 2021 and February 4, 2022, the two marketing agencies spent nearly $65,000 on almost 700 ads placed through the Facebook pages Micolombia (“My Colombia”) and Colombia LIBRE (“Free Colombia”).

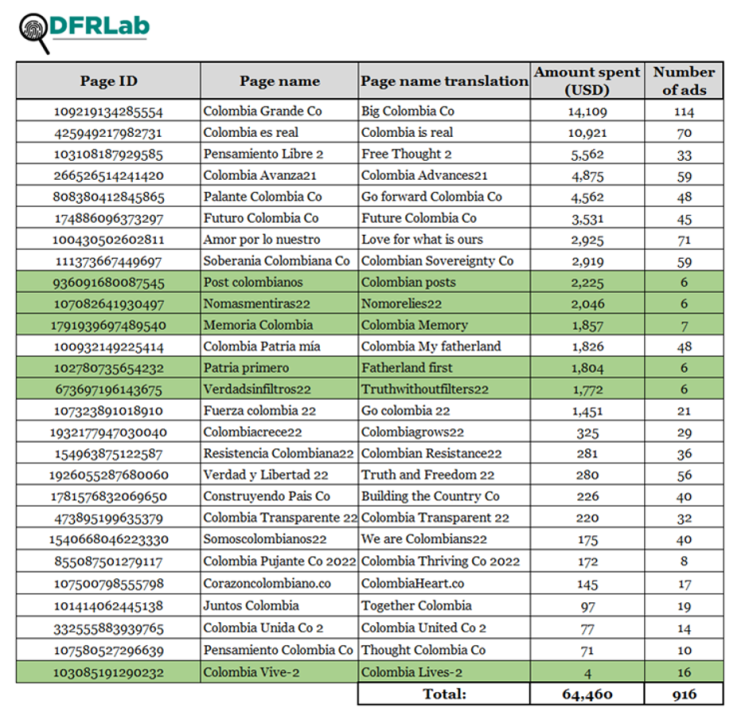

In our latest investigation, we found that after March 24, the network increased the number of assets used, possibly to avoid detection. At the same time, the number of ads and the amount spent on Facebook and Instagram increased monthly. According to Meta’s Ad Library, the new network spent nearly $64,500 over two months (between March 24 and May 27, 2022) on about 900 ads placed through 27 newly activated Facebook pages.

Many of the newly identified assets can be linked to the assets previously used by the marketing agencies Cdigital SAS and Marketing Digital Strategy. The Latin American Center for Journalistic Investigation (CLIP) and the news outlet La Silla Vacía published an investigation on May 19 which confirmed a connection between the two marketing firms and nine of the 27 Facebook pages. The reporting also verified that Cdigital SAS had at least four multi-million-Peso contracts with the mayor’s office of Zipaquirá, a city close to Bogotá. The organization can also be connected to the right-wing think-tank Únete por Colombia, an association that has used its Facebook page to “spread misinformation about Petro” and has among its members political leaders and social media influencers aligned with right-wing political parties and the government.

One day after CLIP and La Silla Vacía reached out to interview a Cdigital SAS member, eight Facebook pages linked to the organization were deleted. The DFRLab identified that at least six pages were created and started to post ads between May 14 and May 27, in what appears to be an attempt to replace the deleted pages. In addition, the members of both marketing firms have either removed or hidden their names from the public databases that were previously used by the DFRLab to expose their connections to the network.

Coordinated campaign

In mid-February, the network began to prepare the websites and Facebook pages connected to the inauthentic campaign. The operators registered domains, changed Facebook account names, and pivoted to posting about Colombian tourism. On March 24, the network launched its first advertisement on Facebook and Instagram.

On Instagram, the DFRLab could not identify any newly created accounts, but we did identify that the account @colombialibre2021 belongs to the network and is still active.

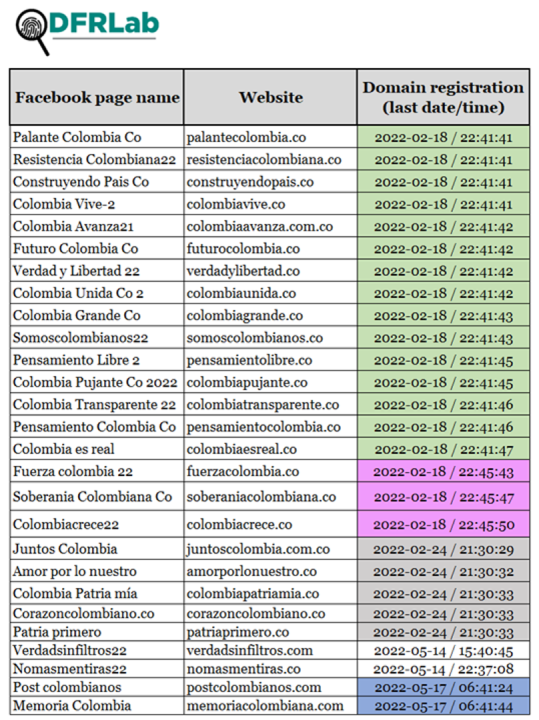

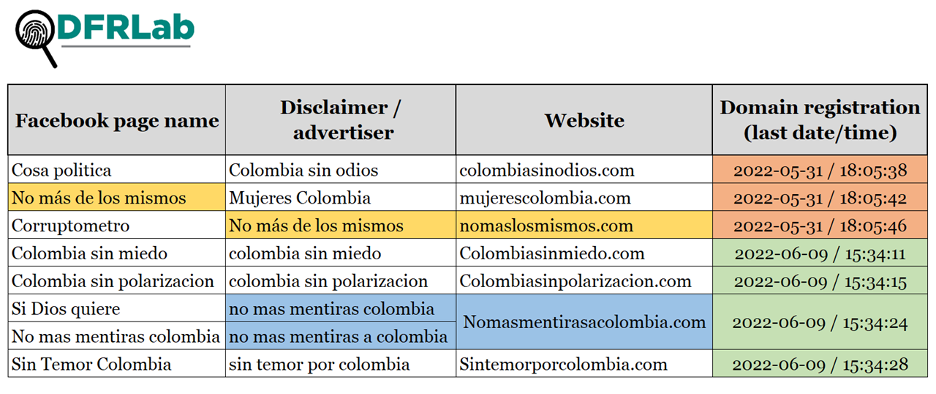

The Facebook pages in this network can be linked by their domain registrations. Each Facebook page lists in its Home section a corresponding website that uses the Facebook page name for its domain. The DFRLab conducted a search using RiskIQ and DNSLytics and determined that the 27 domains tied to the network were registered in batches on February 18, February 24, May 14, or May 17. Many of the domains were registered within the same second, and others within the same minute. In addition to the 27 websites, some accounts used the domain izquierdaextrema.com, registered on May 10, as the destination website for their ads.

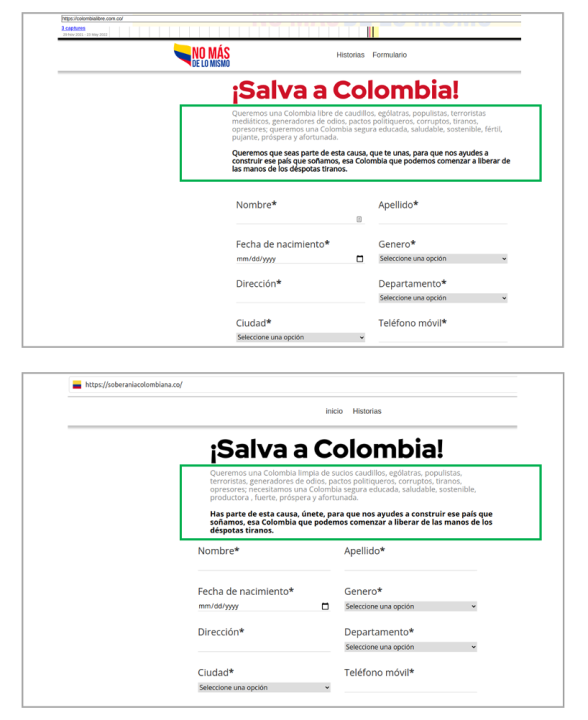

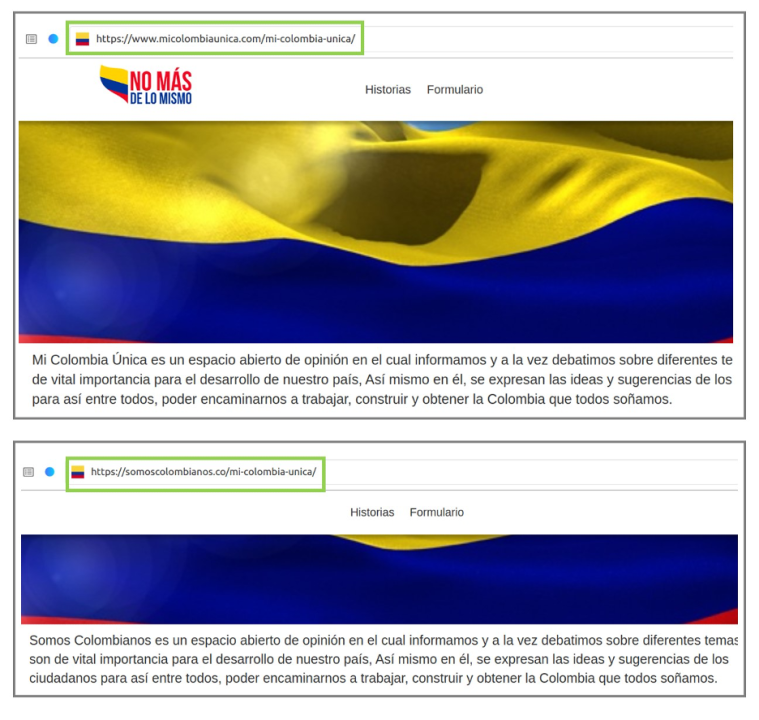

The content on the newly registered websites was similar, and at times identical, to the content posted on micolombiaunica.com and colombialibre.com.co, assets identified in our previous investigation. For example, the About section for many of the newly registered website used the same text and images as micolombiaunica.com, only changing the name of the website. Also, the same web form asking users to join a campaign to free Colombia was seen across many of the websites, with the form’s introductory text varying slightly.

On eight websites, the forms included fine print that lists Colombia Libre as the copyright owner.

The About section of three websites included the name of micolombiaunica.com in their URL.

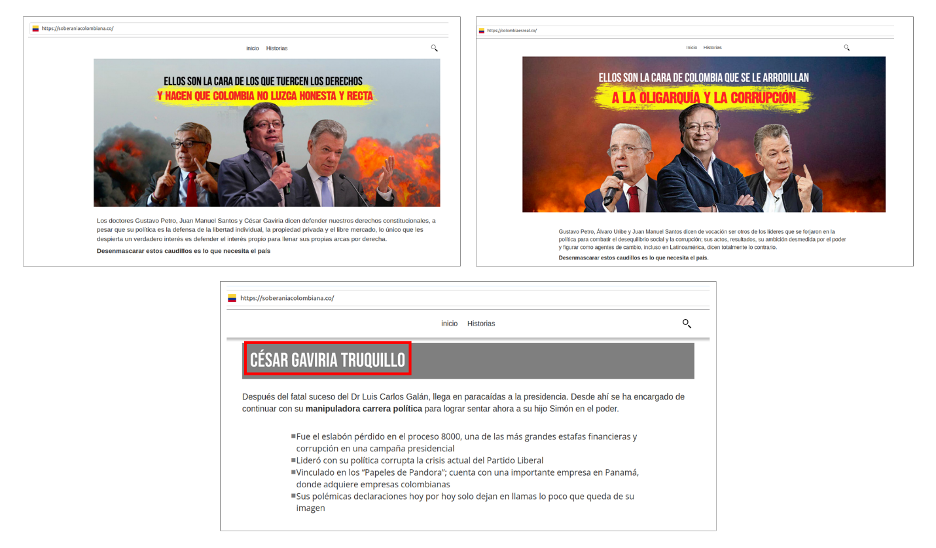

In addition, some websites included short profiles that varied slightly to criticize different presidential candidates and political leaders. For instance, some websites changed the second name of former president César Gaviria Trujillo from Trujillo to “Truquillo” — a pejorative joke meaning “little trick.”

The registrants of all websites were hidden, likely to reinforce the anonymity of the network’s operators. A previous query using RiskIQ on January 28, 2022 showed Cdigital SAS had registered the micolombiaunica.com domain. On February 17, a day before the new websites were registered, a new query revealed that Cdigital SAS hid the identity of the registrant by adding security features to the domain.

Further indicating coordination between the Facebook pages, 15 pages changed their Facebook name on February 25. The Facebook pages Amor por lo nuestro, Colombia Patria mía, and Corazoncolombiano.co were the only accounts created between March 7 and March 8, 2022. The DFRLab could not confirm when the deleted Facebook page Colombia Crece was created or changed its name.

The Facebook pages portrayed themselves as posting organic content under the categories of political organizations, news outlets, or communities. The pages created before February 2022 belonged to businesses and communities, such as restaurants and air sports enthusiasts. After the Facebook names were updated, all the pages began posting about Colombian travel destinations. The pages used the same content and branding that Micolombia and Colombia Libre have used on Facebook and Instagram.

On March 24, 2022, the network began paying for ads that targeted the Colombian presidential elections. Ads against Petro and Uribe were the most prevalent.

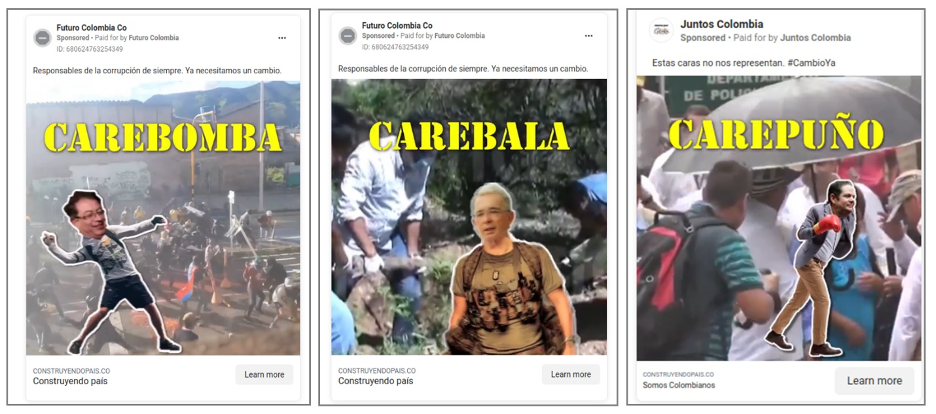

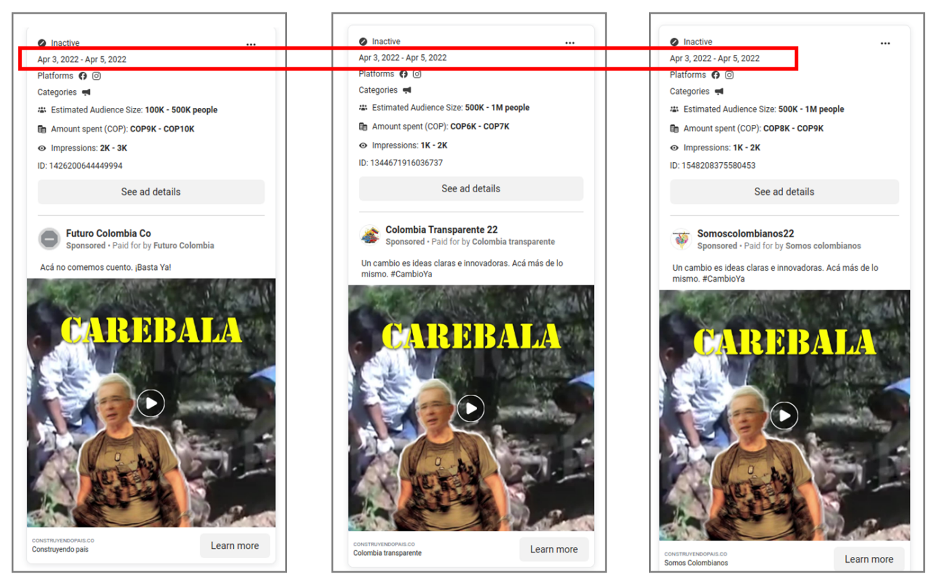

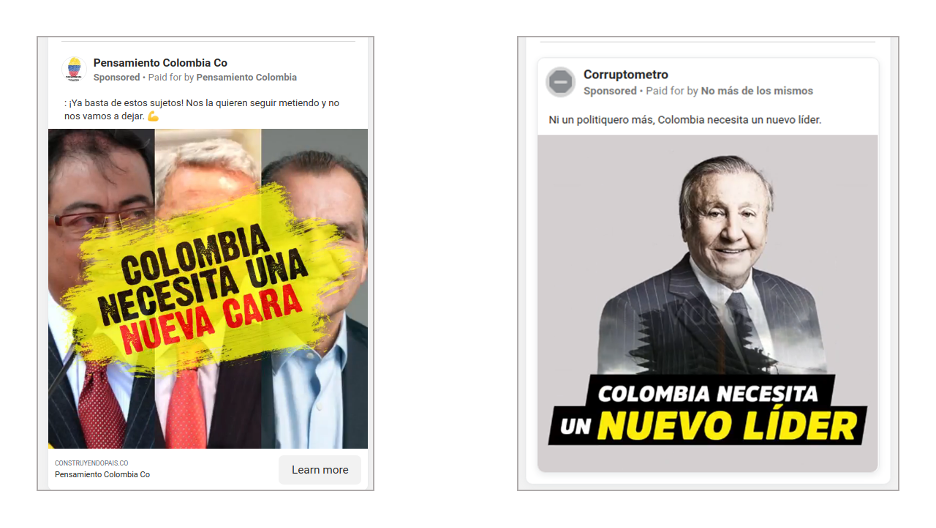

Between April 3 and April 5, six Facebook pages posted ads with videos targeting presidential candidates Petro and centrist Sergio Fajardo, alongside politicians like Uribe, Centro Democratico’s presidential pre-candidate Óscar Iván Zuluaga, and Cambio Radical leader and former vice president Germán Vargas Lleras. The videos superimpose the politicians’ faces on other people’s bodies. The footage also included text that described the politicians as drug addicts, criminals, or criticized their physical appearance. At the end of the video, a line of text reads, “Colombia needs a new face.”

The DFRLab identified on June 22 that Facebook had removed a set of 86 ads, posted by 21 pages, for violating the platform’s advertising policies. The page Palante Colombia Co, which posted a set of 14 ads comprised of 48 posts, was the only account to have all its ads removed. Other pages continued to run ads — some of them including the same content that Facebook had banned elsewhere — which suggests the ads could have been removed after reports from Facebook users. The owner deleted the page Palante Colombia Co after May 23, 2022. As this investigation found, many of the ads on the page violated Meta’s community guidelines on hate speech and showed signs of inauthentic behavior.

Second round of elections

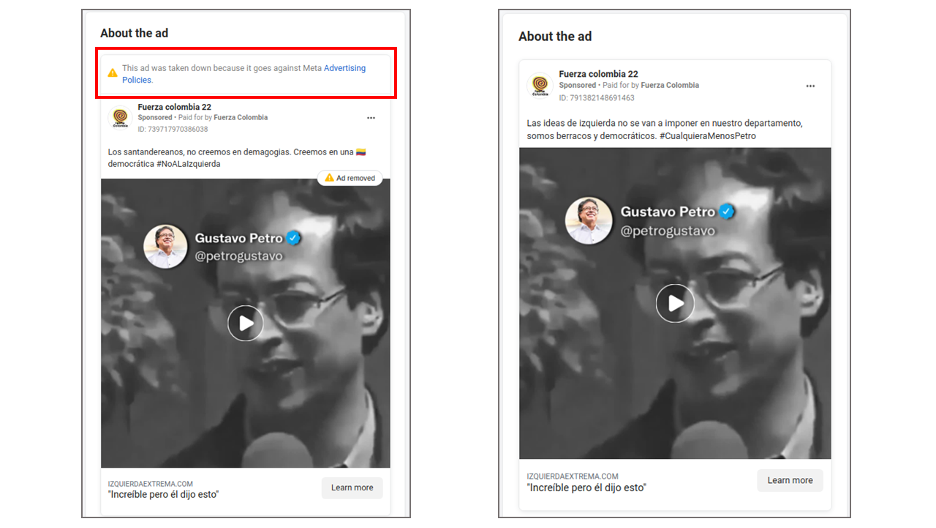

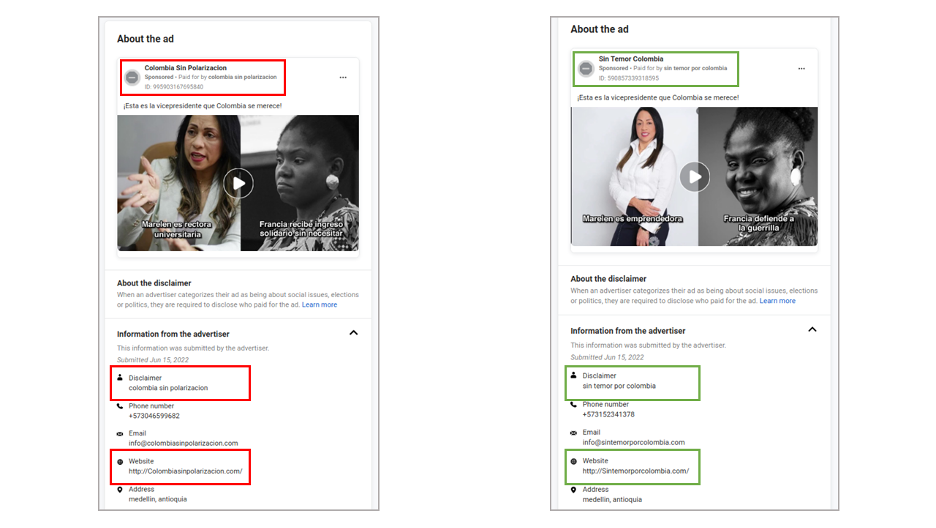

The DFRLab identified another active network during the second round of voting that also targeted Petro and his political allies. The DFRLab could not identify who was behind the eight Facebook pages and seven websites belonging to the network, however, the content and the behavior bore hallmarks of previously identified “disinformation for hire” campaigns. For example, the ads recycled narratives used in previous campaigns to attack Petro, and linked to websites that used the Facebook page or advertiser name in their domain, a tactic known to be used by marketing agencies.

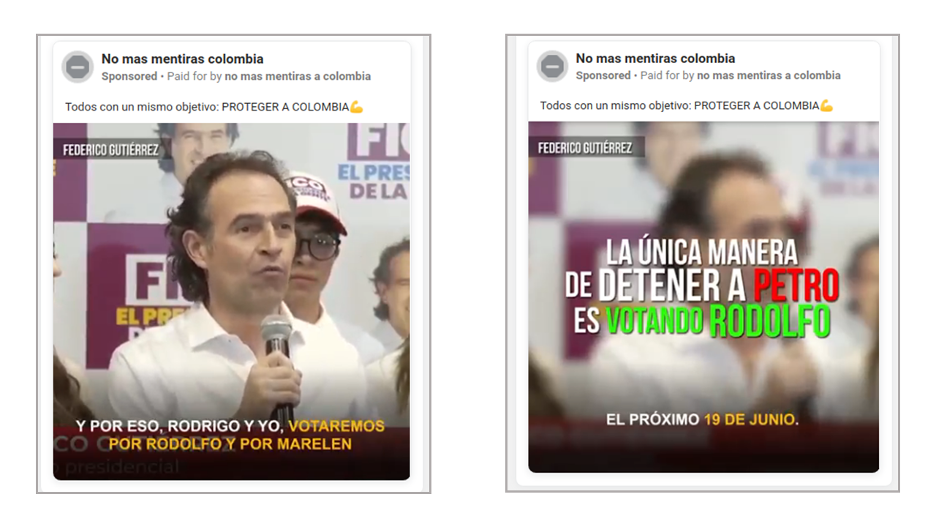

The Facebook pages promoted ads that amplified a narrative that claims Petro and his political allies are the same politicians that have managed Colombia since the eighties. However, unlike the face-swapping ads from the first round of campaigning, which read, “Colombia needs a new face,” these videos ended with a picture of Hernández and a line of text that reads, “Colombia needs a new leader.”

In contrast to the two other networks that attacked Petro, this network openly showed support for other presidential campaigns. Seven out of the eight Facebook pages posted video ads that attacked Petro while supporting Hernández, or Marelen Castillo, his vice-president, or sharing a speech from Gutierrez in support of Hernández’s candidacy.

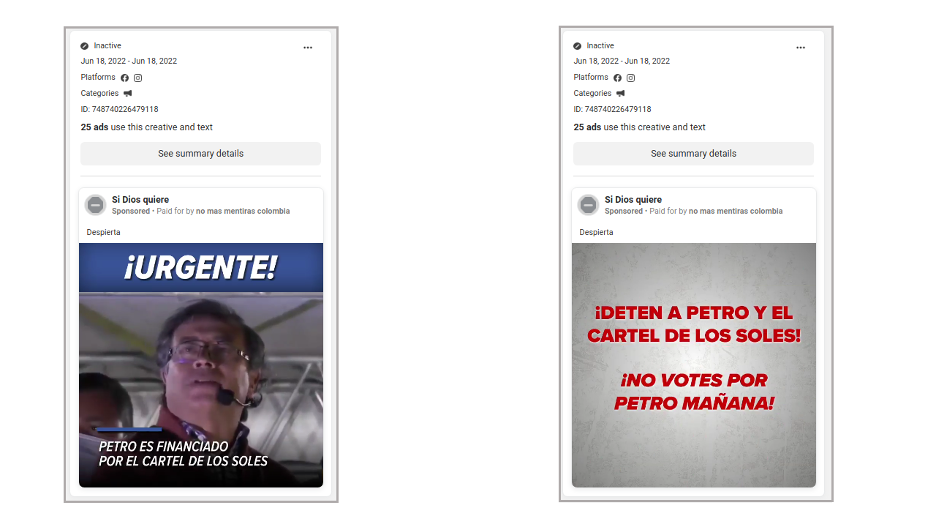

In the network, only one Facebook page — Si Dios quiere — was exclusively used to attack Petro. The page spent over $8,200 on ads on June 18, one day before the second round of voting. Si Dios quiere posted 25 ads containing a video that falsely claimed Petro was paid by the Nicolás Maduro regime and that Petro had not denied the allegation. The claim was related to an announcement claiming former Venezuelan intelligence official Hugo Armando Carvajal Barrios, also known as “El Pollo,” would testify against Petro, as revealed by Colombian magazine Semana on April 19, 2022. However, on April 22, Carvajal retracted the comments. On Twitter in October 2021, Petro denied having any links to the Maduro regime.

In addition to the pages that used the same videos to target Petro, the DFRLab identified other signs of coordination. As shown in the table below, some of the pages shared the same advertiser, whose websites were registered within the same minute on May 31 or June 9, 2022.

Supporting Petro

Other Facebook pages that targeted Hernández and supported Petro invested less in ads than the networks that attacked Petro. The DFRLab determined that the Facebook pages Dato Certero and Notifresh became active during the second round of voting while spreading false and misleading content against Hernández.

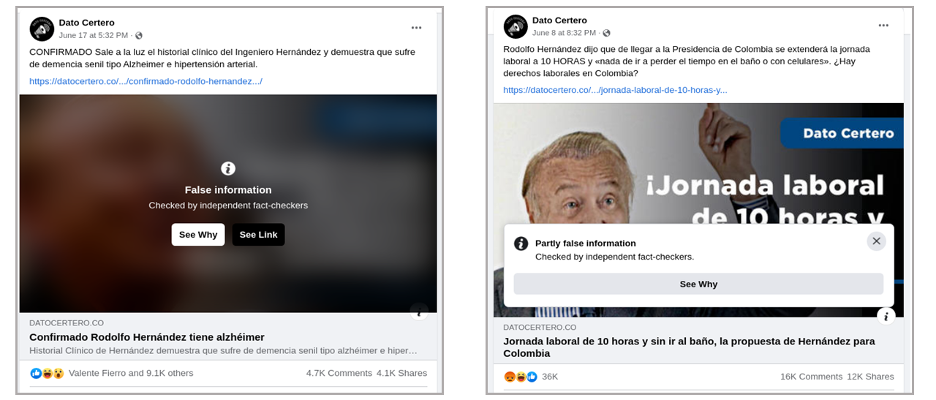

Dato Certero describes itself as an investigative media outlet on its Facebook page and website. The page was created on May 20, nine days before the first round of voting. During that period, Dato Certero posted nine ads targeting Hernandez. Between June 7 and June 19, the Facebook page posted 18 ads that also attacked Hernández.

Facebook removed all ads posted by Dato Certero. Two of the remaining posts, which appear as advertisements as well, feature a Facebook disclaimer saying that the content is false or partly false. Dato Certer spent more than $2,800 on ads. Both the website and the Facebook page of Dato Certero became inactive ahead of the second round of polling on June 19.

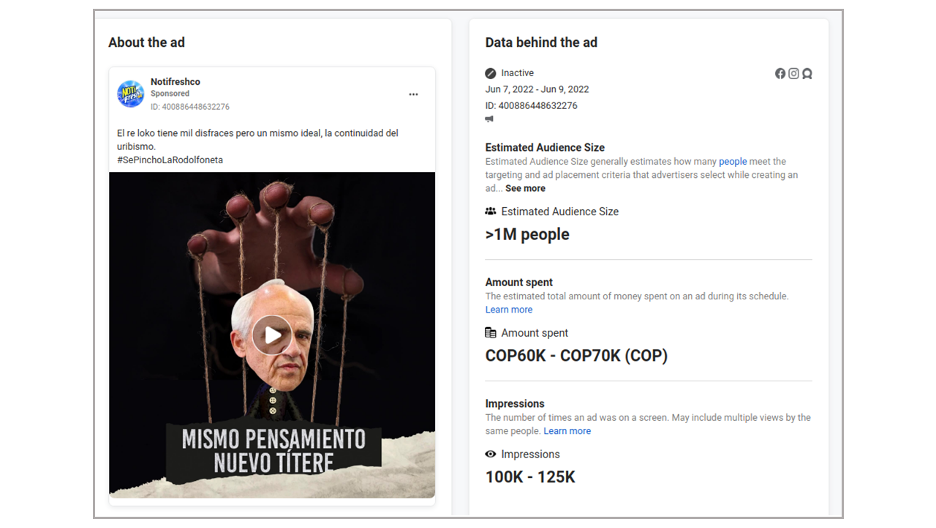

Notifreshco describes itself as a news company on its Facebook page and Instagram account. Notifreshco posted ads that attacked Hernández’s campaign and posted in its Home section news about Petro’s decisions as president-elect, in addition to statements from his political allies criticizing Duque’s government. Notifreshco spent nearly $495 on ads. For example, two ads misleadingly suggested that former president Ernesto Samper supported Hernández, when, Samper had backed Petro during the presidential elections.

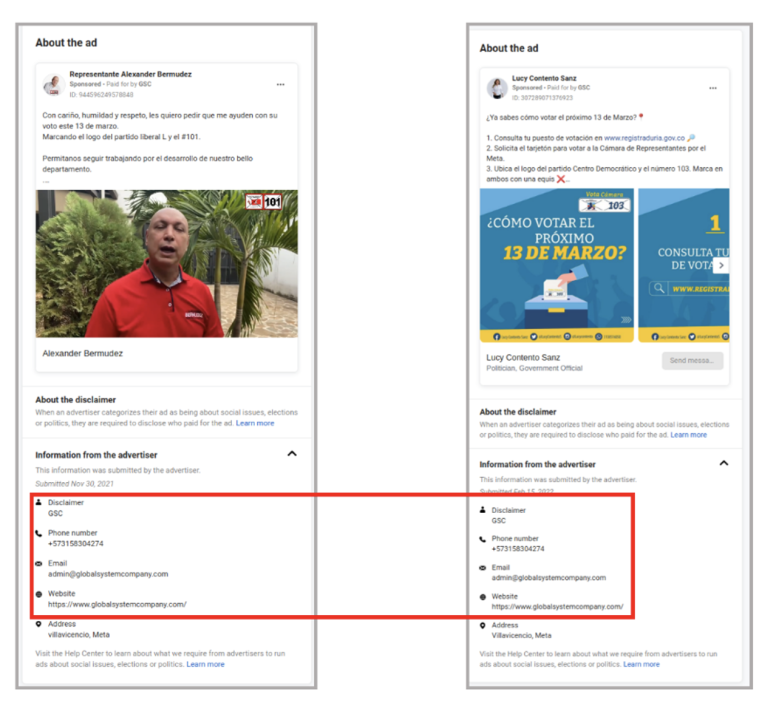

According to Meta’s Ad Library Report, Notifreshco’s advertiser was Global System Company, a PR firm based in the Colombian city of Villavicencio, with offices in Peru and Mexico. Global System Company also appears as the advertiser for campaigns for the former candidate to Colombian congress Lucy Contento and re-elected Congressman Alexander Bermudez. Neither were aligned with Petro, but showed support for either Gutiérrez or Hernández.

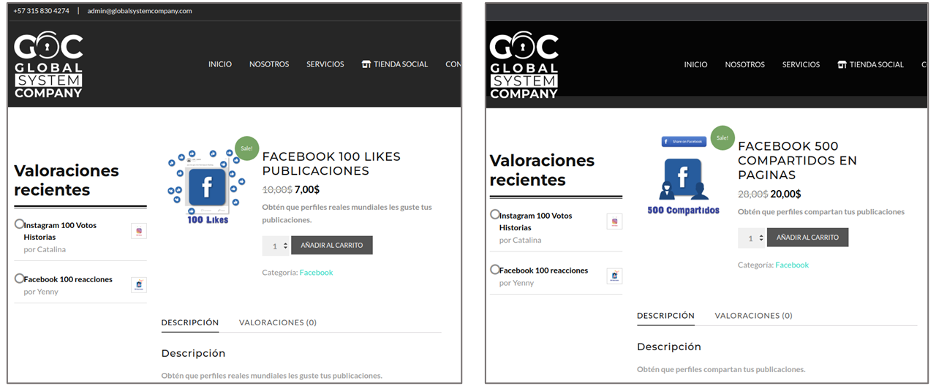

On its website, Global System Company offers services for political marketing, app development, and research on cybercrimes. The company also offers the purchase of hundreds and thousands of interactions on Facebook, Instagram, Spotify, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube. On Facebook, for instance, it offers 100 likes made by “real profiles” for seven dollars and 500 shares on page posts for $20.

The political ads from Global System Company appear to be part of a “disinformation for hire” campaign. These campaigns rely on the environment of polarization that has permeated the digital conversation in Colombia since the peace plebiscite in 2016, and has consolidated with the previous presidential elections of 2018 as well as the social protests that occurred between 2019 and 2021.

While the operations of the network that targeted Petro was exposed and temporarily restricted as a result of publications from researchers, journalists, bloggers, and Facebook removals, the network appears to be adapting to avoid detection, highlighting the challenges social media platforms face when it comes to cracking down on the “disinformation for hire” industry.

Cite this case study:

Daniel Suárez Pérez, “Colombian PR firms used Facebook ads to spread disinfo on presidential candidates,” Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), August 11, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/colombian-pr-firms-used-facebook-ads-to-spread-disinfo-on-presidential-candidates-c44e1ac18bba.