Troubled Waters

Reported Russian deployment of Iskander missiles adds to tensions in Baltic Sea

Troubled Waters

Share this story

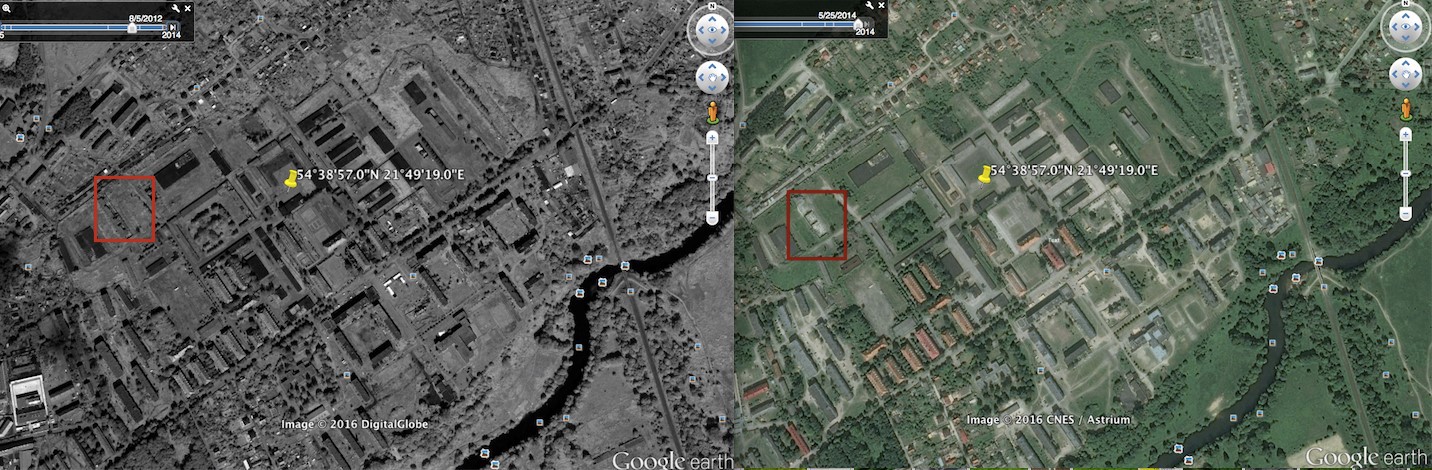

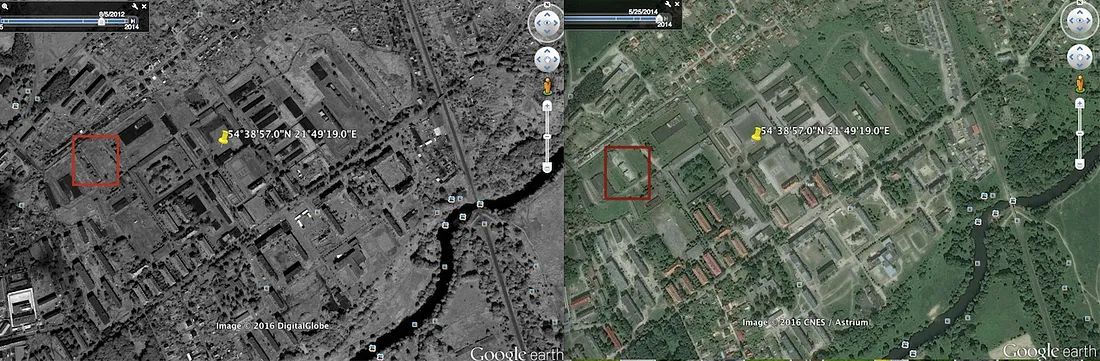

BANNER: Comparison of satellite imagery of Russia’s 152nd Missile Brigade in Kaliningrad, in 2012 (left) and 2014 (right).

On Friday, October 7th, the Estonian state broadcaster reported that Russia was shipping Iskander nuclear-capable missiles to the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, which borders Poland and Lithuania. The report was attributed to a “government source” and was tweeted by the Estonian Permanent Representation to NATO:

ALERT ! #Russia is shipping ISKANDER missiles on civilian "AMBAL" ferry to Kaliningrad – well-informed source says https://t.co/nnp9vdaKv1 pic.twitter.com/lbexM2sjAO

— Estonia at NATO 🇪🇪 (@estNATO) October 7, 2016

The deployment of Iskanders to Kaliningrad has long been seen as a key threat to NATO, especially in Poland and Lithuania. Russian officials, including then-President Medvedev, have repeatedly warned that an Iskander deployment could form part of Russia’s response to NATO’s ballistic missile defense sites in Europe. Furthermore, in May 2015, Major General Mikhail Matvievsky, chief of Strategic Missile Forces and the Artillery of the Russian Ground Forces, reportedly said that a missile brigade redeployed to the Kaliningrad region would be equipped with Iskander-M complexes before 2018. Thus a deployment would represent a significant upping of the ante in the eastern Baltic, but would not necessarily come as a surprise.

The Ship

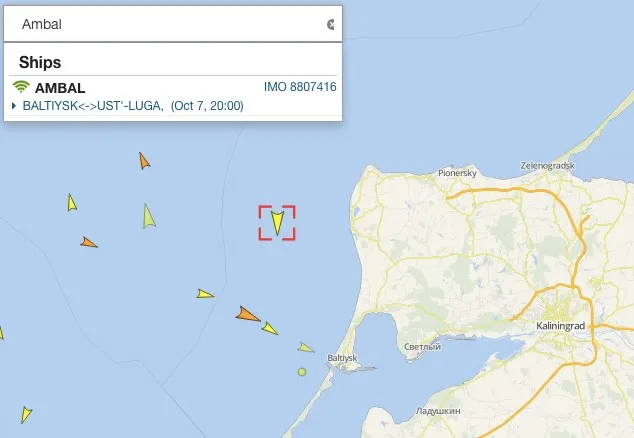

According to the report, the missiles are being carried on the RO-RO transporter “Ambal”, a 188-meter-long ship registered with Russian shipping company AnRussTrans with the International Maritime Organisation number 8807416.

According to online resource vesselfinder.com, the Ambal was reporting in from just off the coast of Kaliningrad at 1500 UTC on Friday, October 7:

The Likely Destination

It would not be the first time that Iskanders have been shipped to Kaliningrad. In December 2014, media reported a temporary deployment as part of an exercise; another incident followed in March 2015. However, in both cases, officials confirmed that the Iskanders had been returned to mainland Russia once the exercises were over. If the report is confirmed —and it has not yet been — then the likely destination for the Iskanders is the base of the 152nd Missile Brigade, based in the Chernyakhovsk Oblast in Kaliningrad (military unit number 54229, located at the coordinates 54°38’57.0″N 21°49’19.0″E). The brigade is currently reported to be equipped with OTR-21 “Tochka” short-range ballistic missile. Any replacement of the Tochkas with Iskanders would represent a major upgrade of their capability, and would be perceived as a direct threat by Poland and Lithuania.

While there is the potential for an upgrade in weapon systems, the base itself did not see significant expansion or construction, as of mid-2014 when the most recent satellite image is available. The images below compare satellite footage (accessed on Google Earth) from 05.08.2012 and 25.05.2014 (most recent). The imagery from 2014 shows a structure in the middle left part of the map (red square) that was not there in 2012, possibly indicating some expansion to the base:

However, upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that the structure existed in 2005, but had disintegrated and been partially demolished some time between 2005 and 2011 and then replaced by 2014.

Now two years old, the most recent image is too dated to give an accurate assessment of current conditions at the base, but does at least provide a baseline against which future imagery can be measured. There are dozens of satellite images that have been captured of this base in 2016, but they are only available via purchase.

Finnish-U.S. agreement in the background

The Iskander report comes in the context of a steep rise in tensions in the eastern Baltic, both by sea and by air.

Also on Friday, the Estonian NATO delegation tweeted that Estonia summoned the Russian ambassador to protest a violation of Estonian airspace.

BREAKING #Russian SU-27 violates #Estonia's airspace. Ambassador summoned to #MFA . #Russian air activity in region increased over past 48h pic.twitter.com/yVGou4ORbC

— Estonia at NATO 🇪🇪 (@estNATO) October 7, 2016

One day earlier, the Defense Ministry of Finland announced that it had detected two “possible violations” of its airspace by two different Russian aircraft in the space of seven hours, adding that the Finnish Border Guard would investigate the incident. The statement said that “during Thursday the Russian military aviation over the Baltic Sea has been intense.”

The violations came hours before Finland and the United States signed a Statement of Intent on bilateral defense cooperation — although the Finnish Defense Ministry was careful to point out that, in keeping with Finland’s tradition of neutrality, it is a “general working document that is not legally binding on the parties and it contains no defense commitments between the countries.”

A Pattern of Confrontation

However, these incidents also fit into a larger context of confrontation in the Baltic which has been ongoing since NATO agreed, at its summit in Warsaw in July, to deploy 4,000 troops to the Baltic States and Poland to secure alliance’s eastern flank. The Kremlin interpreted the decision as a hostile act against the Russian Federation and pledged to respond.

The accompanying map shows incidents over the past three months in which Russian military forces have staged large-scale or snap exercises, Russian ships have been spotted close to NATO waters, or Russian aircraft have been intercepted by NATO air policing units in the Baltic States. (The mission is often, and inaccurately, called “NATO’s Baltic air policing mission.” In fact, air policing is a mission carried out right across NATO territory. The Baltic element is a part of that larger mission, but is entirely carried out by other NATO members.)

July

In July, when the decision to deploy the troops to NATO’s eastern flank was announced, there were at least five incidents which could be seen as exacerbating tensions. A Russian spy was charged with trying to recruit Lithuanian officials to bug the home of the Lithuania’s President Grybauskaite. On the same day the decision to deploy troops was announced, a Russian bomber IL-22 approached Latvia’s border. A couple of days later, NATO aircraft intercepted a Russian aircraft flying without transponders over the Baltic Sea airspace.

(A plane without transponders makes itself invisible to civilian airliners that do not have the high-tech radars needed to spot the jets early enough to avoid risk of collision; this ‘invisibility’, combined with the highly irregular flight patterns these jets follow, make them a serious risk to the safety of civil aviation.)

Meanwhile at sea, on July 17th and 23rd Russian warships were spotted coming within five miles of Latvia’s territorial waters; their presence was tweeted by the Latvian Armed Forces. On July 29th, the Latvian forces reported a “Steregushchy” class corvette coming within 2.5 nautical miles of its territorial waters.

LV ekskl. ekonom. zonā 2.5 j.j. no terit.jūras bruņotie spēki 29.07. identif. Krievijas BS "Steregushchy" klases korveti “Stoikiy”

— NBS (@Latvijas_armija) July 29, 2016

Latvian armed forces tweets reporting the approach of Russian corvette “Stoikiy” to within 2.5 NM of territorial waters, 29 July 2016

In total, in the last two weeks of July, the Latvian forces reported sightings of 14 Russian warships (including a “Kilo” class submarine) between 2 and 25 NM from Latvian territorial waters — indicating both the level of Russian activity, and the degree of concern caused in Latvia.

August

In August, Russian fighter jets were reported as flying over Baltic airspace without transponders a total of four times — on the 1st, 16th, 30th and 31st. On the12th, Russia’s armed forces in the Western Military District (bordering the Baltic States and Poland) were put on high alert without any warning and on the same day, NATO’s Baltic mission spotted a Russian military aircraft near Latvia’s airspace. On 16th and 17th, Russia held military exercises, one for naval and another for land troops, both near Russia’s Baltic and Polish borders. Lastly, on 25th, Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered army drills in several military districts, including the Western District.

September

In September, Russian fighter jets were reported as flying through Baltic airspace without transponders switched on 13 times: twice on September 2nd and 22nd, once on 4th, 9th, 13th, 14th, 16th, 17th, 19th, 20th and 23rd. Apart from that, on August 3rd, Russian submarines and warships came near Latvia’s sovereign waters. On the 6th, Estonia accused a Russian AN-72 transport aircraft of violating its airspace, while the German aircraft conducting the mission from the Ämari air base were scrambled to intercept a Russian TU-134 transport aircraft and two SU-27 fighters flying without transponders.

Cold winter, heated situation

Against this backdrop, a Russian deployment of Iskanders to Kaliningrad would not be surprising. Since the NATO announcement, tensions have grown in the eastern Baltic, and in parallel, neutral Sweden announced in mid-September that it would resume a permanent military presence on the island of Gotland.

Russia consistently portrays NATO as a threat, and has long warned that it could station Iskanders in Kaliningrad. Officials have repeatedly warned of the possibility since at least 2010:

A chronology of Russia’s rhetoric on Iskanders in Kaliningrad

2016 June 30

2016 June 23

2016 May 30

2015 May 13

2016 April 29

2015 September 23

2015 August 21

2013 December 13

2012 May 03

2011 November 23

2010 February 08

If confirmed, an Iskander deployment would give Russia a powerful new military capability in a key strategic area. It would also serve as a political signal to NATO, although such a signal would likely be interpreted in different ways by different member states. While the Iskander deployment is not yet confirmed, the broader pattern is clear. Friction is clearly rising around the Baltic States and the eastern Baltic more broadly. The winter will be cold (indeed “Baltic” is Scottish slang for “freezing”), but the security situation is likely to get hotter.